Political Repression in Rwanda: Widespread Arrests of Journalists and Opposition Politicians

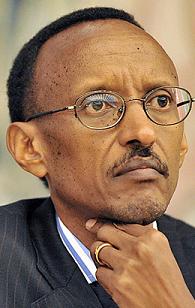

In five weeks, Rwandans will go to the polls to elect a President. The incumbent, Paul Kagame, head of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front, continues to exert total control over the country’s election process.

In advance of the upcoming presidential elections, many within the international community have remained supportive of Rwanda’s so-called “democratic transition.” They seem to ignore the widespread arrests of journalists and opposition politicians, the closing of independent Rwandan newspapers, ejection of a Human Rights Watch researcher, an assassination attempt against exiled General Kayumba Nyamasa who had a falling out with President Kagame, and the killing of journalist Jean-Leonard Rugambage who attempted to report on the assassination attempt in the online version of a Rwandan newspaper whose print edition had been closed down by the government. While diplomats from some countries, like Sweden and the Netherlands, have cut their aid, the US and the UK continue to publicly support Kagame. As an American diplomat based in Kigali said, “Of course this government is not perfect. But no government is. The position of many in the diplomatic corps is to gently nudge the RPF towards democracy”.

While diplomats quietly acknowledge this repression of elites, there is no public acknowledgement of the impact of the elections on average Rwandans.

In Rwanda, politics is the preserve of elite actors, who represent around 10 percent of the population. Average Rwandans such as rural farmers, teachers, nurses, low level civil servants and traders who make up the remaining 90 percent of the population have virtually no say in politics. In November 2009 a group of rural farmers resident in southern Rwanda sought to register a new political party to put forward their own presidential candidate. Several of them were arrested without charge, and the presumed organizers remain in prison; the rest fled to neighboring Burundi. As the Swahili proverb goes, “When elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers”.

A climate of fear and insecurity predominates in the everyday life of average Rwandans. Anyone who questions RPF policies or its treatment of its opposition and critics can be beaten, harassed or intimidated into submission. Those perceived as sympathetic to the political opposition can be arrested, “disappeared,” or like Rugambage, murdered. The number of political prisoners as well as those who have disappeared is unknown, but is part of a broader strategy, according to Human Rights Watch, to “silence critical voices and independent reporting before the elections”.

The strategy of repression means that none of the three main opposition parties – Democratic Green Party of Rwanda, FDU-Inkingi and PS-Imberakuri – can take part in the elections. Family members of opposition politicians and critical journalists find themselves under constant surveillance. The majority of Rwandans wait anxiously for the elections, hoping that they are perceived as “good democrats” so as to avoid attracting unwanted attention from the government.

Average Rwandans recognize the upcoming presidential elections as a form of social control to ensure they vote for the right party (Kagame’s RPF). An aide to the Minister of Local Government told me, “In 2010, the people will vote as we instruct them. This means that those who vote against us understand that they can be left behind. To embrace democracy is to embrace the development ideas of President Kagame”.

As a male university student told me, “Oh, voting is not something done freely. Since mid-2009, students are told to take an oath of loyalty to the RPF. This means that we have to join the RPF – if we don’t we don’t have any opportunities to get a job or get married or have any kind of life really. In Rwanda, power of the RPF is absolute.” A rural woman who lost her husband in the 1994 genocide told a similar tale, “Democracy is something we need when the government fears losing power. We heard this before the genocide, and we hear it now. Democracy would be okay if we could actually participate rather than being forced to vote!”

For average Rwandans, politics is the domain of the elite, who intimidate and harass the rural population into parroting the so-called democratic ideals of the RPF. This democracy is an alienating and oppressive daily reality—something which could crystallize into violence in early August 2010 when Rwandans go to the polls again. The words of a Rwandan colleague are emblematic, “Anyone who has the means is trying to get out of the country. For those who cannot, we hope the elections are without violence. When the government can imprison or kill anyone they please, we are all nervous because none of us are safe…”.

Susan Thomson is a Five Colleges Professor, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, at Hampshire College, Amherst, Ma. She has been researching state-society relations in Rwanda since 1996 and has authored numerous publications on the country’s politics.