“Pogrom”: From Kishinev in Tsarist Russia (1903) to Gaza, Palestine (2023)

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Pogrom. This Russian term denotes a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring Jews and destroying their property. One of the deadliest pogroms (50 Jews were killed and nearly 600 wounded) took place in Kishinev [Chișinău, Moldava] a hundred and twenty years ago, in April 1903. But the trauma of Russian Zionists facing the oppression in Tsarist Russia over a century ago continues to inform Israel’s political culture.

The Russian word has been widely used by Israelis to characterise the Hamas attack on Southern Israel in October 2023. It had also been used before. For example, an Israeli general employed it a few weeks earlier when armed Zionist settlers attacked the Palestinian village of Huwara on the occupied West Bank.

These attacks have intensified since. The term appears appropriate since gun-toting Israeli vigilantes were attacking unarmed civilians.

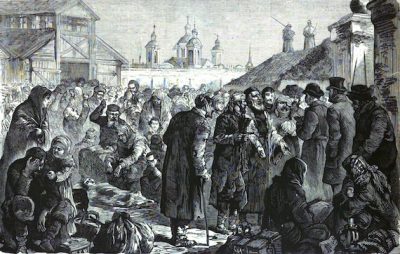

Kieff (Rusia).—La expulsión de los judíos eslavos: familias israelitas abandonando sus hogares. Public Domain, Link

However, the use of this term for the Hamas attack has provoked debate. Some argue that Hamas conducted the operation as an act of resistance against one of the best armed states in the world. They would not call the attack a pogrom because it was ultimately directed at a powerful state enforcing a system deemed oppressive and illegitimate by its victims.

Others put emphasis on the purely civilian targets of the attack such as the music festival which may justify the use of the Russian word. They attribute the Hamas attack to antisemitism, i.e., unmotivated hatred, rather than see in it a reaction to decades of suffering and misery inflicted by the Zionist state.

However, within the state of Israel, despite its formidable military might, including nuclear weapons, the term has caught on. It was claimed that the number of Jews killed on one day in the Hamas attack was the highest since the Nazi genocide. This drew a direct line with the Nazi genocide and created the impression that Jews were once again powerless in the face of “pure unadulterated evil”, as the U.S. President put it.

When, two weeks into Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, the U.N. Secretary General reminded the world that the Hamas attack had not happened in a vacuum, Tel Aviv indignantly called for his resignation.

There is little tolerance for any mention of the Israeli blockade of Gaza since 2007, and, more generally, of Israeli responsibility for the dispossession, deportation, and murder of Palestinians since 1947.

These look like the manifest cause of the Palestinian resistance.

Most Israelis also prefer to ignore the fact that the millions of Palestinians trapped in Gaza are largely descendants of those that the Zionist militias and the Israeli military expelled from their homes in what is now the state of Israel. Israeli officials and its fans elsewhere usually deploy arrogance and self-righteousness to reject rational debate about the Hamas attack.

Besides the obvious political purposes of this PR strategy, one can notice a genuine embrace of the term “pogrom” in Israeli society at large.

Ideologically committed Zionists used to treat pogrom victims of over a century ago and survivors of the Nazi genocide with shame and disdain. They were blamed for lacking the courage to fight, for “going as sheep to the slaughter”.

Haim Nahman Bialik, who later became a cultural icon in Israel, in a poem written following the Kishinev pogrom, castigated the survivors, heaping shame upon their heads. Bialik lashed out at the men who hid in stinking holes, “crouched husbands, bridegrooms, brothers, peering from the cracks, “while their non-Jewish neighbors raped their wives and daughters. This poem, in the Russian translation by Vladimir Jabotinsky, remains one of the strongest literary depictions of the pogrom.

Brenner, another poet and like Bialik the son of a pious Russian Jewish family, radically transformed the best-known verse of the Jewish prayer book “Hear, O Israel, God is your Lord, God is one!” one of the first verses taught to children and the last to be spoken by a Jew before his death. Brenner’s revised verse proclaimed: “Hear, O Israel! Not an eye for an eye. Two eyes for one eye, all their teeth for every humiliation!”

This is how these and many other Zionist writers stoked the fires of revenge and violence. As the Diaspora Jew was a coward, so the Zionist Jew — the New Hebrew, the Israeli Jew — must be a warrior.

Later, recognized as the collective legatee of the victims of the Nazis, the state of Israel was awarded crucial financial resources from West Germany and other countries. At the same time, a transformation was taking place: while it was becoming militarily stronger, the state of Israel was claiming to be recognized not only as a legatee of past victims but as an actual collective and righteous victim in its own right.

The Eichmann trial in 1961 marked a watershed in this respect. From then on, the state of Israel has emphasised its continuity with the victims and introduced Holocaust studies into public education. Israeli officials argue that their country is unfairly treated as a harmless collective Jew. In the face of opprobrium for the mass bombing of Gaza in 2023 the Israeli delegates at the United Nations started wearing yellow six-pointed stars, like those imposed on the Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The pretense of being a blameless victim justifies Israeli reliance on military force. “Ein brera!”, “we have no choice” is a common Israeli explanation of violence. Jabotinsky formulated the Zionist concept of the Iron Wall, of terrorising the Arabs into submission, and published it in Russian in 1923. His concept is being reconfirmed a century later. Moreover, political compromises with the Palestinians appear suspect and dangerous. Israeli Prime Minister Itzhak Rabin who tried to reach such a compromise was assassinated, effectively putting an end to the idea of a Palestinian state next to Israel.

The European Jewish memory of victimhood has been maintained, cultivated, and transmitted to future generations of Israelis.

The collective memory of the pogroms in the Pale of Settlement and the death camps in Poland has been inculcated in Israeli schools. All the students, whether or not their ancestors suffered at the hand of the Nazis, are led to make the same conclusion: Arabs attack us just because we are Jews. No wonder this is the way many Israelis view the Hamas attack, which enables them to support the massive violence being inflicted on the Palestinians.

Since October 2023, comparisons of Palestinian resistance with the Nazis have acquired a new life. One of the best-known precedents belongs to Menachem Begin who, during Israel’s first invasion of Lebanon, compared Arafat to Hitler.

This was meant to make the massive bombardment of Beirut in 1982 appear morally sound. Such comparisons are now used to justify a much deadlier bombardment of Gaza. The proportion of civilian casualties in these bombardments surpassed that of all the cases of warfare in the 20th century.

The state of Israel tends also to dehumanize the Palestinians to vindicate what many experts qualify as genocide. An Israeli high school history teacher was put in solitary confinement for making Facebook posts showing the names and faces of a few of the 18,000 Palestinians killed during Israel’s assault on Gaza. The Zionist state apparently considers humanizing the Palestinians an existential threat.

The paradigm of the Kishinev pogrom is rallied to provide a moral carte blanche for the Israeli destruction of Gaza.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Yakov M. Rabkin is Professor Emeritus of History at the Université of Montréal. His publications include over 300 articles and a few books: Science between Superpowers, A Threat from Within: a Century of Jewish Opposition to Zionism, What is Modern Israel?, Demodernization: A Future in the Past and Judaïsme, islam et modernité. He did consulting work for, inter alia, OECD, NATO, UNESCO and the World Bank. E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.yakovrabkin.ca

Featured image is from Informed Comment