Inside the Horror Show of Northern Uganda

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) began as an evolution of the ‘Holy Spirit Movement’—a rebellion against president Museveni’s oppression of northern Uganda, led by Alice Lakwena.

The Acholi people of the north had allied with Museveni’s rival in the Ugandan bush war, Milton Obote (Ugandan President 1961-1971, 1980-1985), and were subjected to reprisals.

When Alice Lakwena was exiled, Joseph Kony took over, changing the name of the group to the Lord’s Resistance Army. As the group lost regional support, he quickly started a trend of self-preservation that would come to characterize the rebel group, stealing supplies and abducting children to fill his ranks.

The LRA terrorized northern Uganda for two decades. In 2006 they indicated an interest in peace negotiations. These were hosted by Juba, Sudan (now South Sudan), and dubbed the Juba Peace Talks.

Meanwhile the LRA set up camp in Garamba National Park in northeastern Congo, gathering its strength and stockpiling food. There was significant evidence that Kony ordered his fighters to attack villages and abduct children in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo) during the peace talks.

Source: wikipedia.org

In August 2006, a Cessation of Hostilities agreement was signed by the LRA and the government of Uganda. The talks took place over the course of two years.

Kony sent a delegation to negotiate on his behalf. But when the Final Peace Agreement was ready to be signed, he repeatedly postponed the date of signing or failed to show up. Most notably, he failed to show up to sign the Final Peace Agreement with the Government of Uganda in April 2008 and November 2008. It is believed that Kony may have entered peace talks as a means of resting and regrouping. The entire time that the LRA was involved in peace talks, they were provided with food, clothing, and medicine as a gesture of good faith.

Operation Lightning Thunder

In December 2008, when it became clear that Kony was not going to sign the agreement, Operation Lightning Thunder was launched. It was the coordinated effort of Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and Sudan, with intelligence and logistical support from the United States.

The operation failed. Joseph Kony somehow learned of the attack in the hours before the air-raid and was able to escape. In retribution for the attempted attack, the LRA, led by ICC-indictee Dominic Ongwen, attacked villages in the DR Congo on December 24, 2008, killing 865 civilians and abducting 160 more over the course of two weeks. The LRA fighters were reportedly instructed to target churches, where people would be gathered with their families for Christmas Eve services.

LRA soldiers survey the bodies of victims of another massacre in the war in northern Uganda. (Source: coalitionfortheicc.org)

A year later the LRA reprised the Christmas massacres in the Makombo region of northeastern Congo as a reminder of their powers of destruction. These attacks took place over four days, December 14-18, 2009. This time they killed 321 people and abducted 250. Because of the remote location of the Makombo massacres in December 2009, the outside world knew nothing about the attacks until three months later. Human Rights Watch broke the news internationally on March 28, 2010.

Since Operation Lightning Thunder, the LRA has functioned in small, highly mobile units across the porous border regions of DR Congo, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan. The African Union was leading counter-LRA efforts, with a large military contingent from Uganda. These efforts were assisted by U.S. military advisers, who have been present in the region since 2011. This advisory mission was expanded in March 2014 to include the use of four V-22 Ospreys; the cap on U.S. personnel tripled from 100 advisers to a maximum of 300.

Starting in 1996, the Ugandan government, unable to stop the LRA, required the people of northern Uganda to leave their villages and enter government-run camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs). These camps were supposedly created for the safety of the people, but the camps were rife with disease and violence. At the height of the conflict, 1.7 million people lived in these camps across the region in squalid conditions with no way to make a living. Thus, a generation of Acholi people were born and raised in criminal conditions.

Water hole outside refugee camp in northern Uganda where 1.7 million people have been displaced. (Source: rightscorridor.com)

Consider the testimony of a former LRA abductee below:

Abduction

“I was in Primary 2 when I was abducted. I was coming home for lunch and as I rounded a bend, eight rebels suddenly appeared and aimed a gun at me. They dared me to run or else they would shoot me. They took my books and tore them all, and tied me up.

One person was made to guard me and asked me if Ugandan People’s Defense Force (UPDF) soldiers like patrolling that route. I denied but they maintained their ambush. At five o’clock in the evening, I heard gunshots and after a short while, four rebels were shot dead by the UPDF.

When the others came back, they then decided to kill me because I had deceived them and made them lose four soldiers. They tied me up again but one of them decided that I should not be killed. I had lost all hope of living again, and my heart pounded loudly, and still, I believed they would kill me during the night.”

Life in the Bush

“We walked most of the night and the next day in the evening we met a bigger group. The four rebels each wanted to take me to join his household at the time of distribution of captives, but their commander prevented a quarrel erupting by taking me for himself. I became his escort and would go with him to the battlefront. I carried his bag, tent and hoe. When we went for operations two times, he recommended that I should be given my own gun because I am not afraid and I am well disciplined.

The next day I proved my worth at battlefield during an attack by the UPDF. I charged them and got four magazines of ammunition and the commander gave me two very important assets. One day after several operations, I threw away my gun during a battle, but I was forced to go back and get it or else I would be killed. I fought at Opit, Lagile, Lira, Aromo and many times at Soroti.

At Soroti, I was given [orders] to kill a man but I refused, so I was slapped with a machete on my bare back and was about to be killed. I gave in and killed the man by hitting [him] on the head with a club. Another man was brought and again I refused and I was beaten severely, until I killed him. I could not eat for three days because of the sight of blood. I also witnessed commander Tabuley killed during a battle. He was shot at the neck and his escorts carried him away. I was also shot on the head but was not badly injured. We also laid an ambush and shot a bus along the Lira-Soroti road; only two people survived whom we took captive, a man and a child.

Thereafter we suffered several attacks by the UPDF. We also attacked a UPDF detachment: we were 40 in number but we were repulsed and 16 people were killed and only I and three others were not injured. Some of the casualties were ghastly to look at.”

Life in Sudan

“Joseph Kony the Commander sent a message that sodas, soap, clothes and other supplies be taken. We walked from Lira district and took 3 days to enter Sudan.

We suffered hunger and six recruits (children) died of hunger. We had to attack Pajok in Sudan (occupied by the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army—SPLA) for food. We walked through the Imotong Mountains and many people died of fatigue and hunger while climbing.

After six days of trouble, even attacks by Lotuko Militias, we reached the other side of the mountain and met Joseph Kony who insulted us and warned us not to escape. Thereafter he planned a mission to raid the Morule of cattle and they brought over six hundred cattle. They counter attacked twice but were repulsed. The SPLA also attacked us for the cattle and we realized them to be tough soldiers.”

Escape

“In March we suffered a heavy attack by UPDF helicopter gunships and a woman, child and two boys were killed. The commander Vincent Otti ordered that everybody should spread out and move alone to avoid casualties. I took this chance to escape: I went and got lost but kept moving for four days without any food and water. I carried my gun and ammunitions pouch. I reached the river Nile on the fifth day and drank water at a certain point, dodging SPLA soldiers who were fishing.

I walked and followed the river upstream and went and drank water again, but when I stood up and moved, I heard something following me in the water. I looked back and saw a dark, large animal like a bull. It began to move in upon me, looking straight at me, its tail up and its eyes dark and terrible. I realized it was a buffalo, very dangerous.

I was feeling very weak and felt dizzy with hunger. I turned to look ahead, and I saw an SPLA soldier take his gun and aimed at me. He said ‘de munu,’ meaning ‘Who are you?’ in local Arabic and began to fire at me. I was too weak to react and the bullets clouded me in dust.

I turned round and saw the buffalo, mad with anger but undecided whether to charge or not, partly distracted by the bullets. I was in a dilemma. I held my gun at a firing position but did not cock it and tried to decide which way to go. I decided that I better be killed by men, not this cruel and terrible buffalo. The man completed a whole round of ammunition and I wasn’t hurt, but during this interlude, over thirty SPLA soldiers came in and released a volley of bullets at me. I fell down by instinct and crawled to a nearby outcrop of rock.

I looked back and saw the buffalo, mad with rage and intent upon crushing me as it followed me. My attackers released a rocket-propelled grenade, which split the outcrop of rock and almost crushed me as it rolled past. They thought I was the one rolling so they directed their line of fire towards the spot where the rock stopped. I creeped and looked back from among the rocks and the buffalo had disappeared.

My attackers were surprised when I stood up again and leaned against a tree. One of them (whom I later realized to be an Acholi from Atiak in Uganda) became inquisitive and came over and ordered me to throw my gun and pouch down. I responded but he ran back in fear. He came again and I threw the gun down and my pouch too. He snatched it and ordered me to follow him.

The SPLA everywhere shouted ‘Kill him’ but the man refused. We reached their barracks amidst insults and many people wanted to stone me. The SPLA had always suffered at the hands of the LRA and I now faced their anger alone. A woman who carried firewood had a machete in her hand and cut at me and missed my face. I clung to the man called Otim, and he protected me for a week until one day he sent a message to Attiak and UPDF soldiers came and took me across the border to Uganda. The SPLA followed me but the UPDF refused to release me. I was subsequently brought to World Vision Children’s Centre at Gulu.”

Amidst War and Death: Profits for a Few

Amongst those affected by the war in northern Uganda, it is sometimes difficult to disentangle victims and perpetrators. For more than a decade, starting in the early 1990s, young Acholi boys and girls followed their parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts into one of the hundreds of displaced camps created by the government of Uganda.

The rebels abducted tens of thousands of children and youth, and if they did not escape or were released shortly thereafter, they were trained, given a weapon and made to fight. As the abducted girls matured, they were forced to marry rebel commanders and give birth, fulfilling the spiritual vision of Joseph Kony to create a “New Acholi.”

The war took so long partly because Museveni and his commanders were making huge profits from the war, and it was around that time when “ghost soldiers” were created by then Army Commander Major General James Kazini and his senior commanders who were active in the Northern conflict.

A whole Brigade of 700 soldiers was created; yet it did not even exist but continued to draw taxpayers’ money in salaries every month. This money ended up in Kazini’s pocket and his commanders.

The United States of America and UK also contributed to prolonging the conflict as they contributed troops that offered training to the UPDF, bought military hardware and gave cash to the Ministry of Defence for maintenance of equipment. It is the flow of such money which ended in individual bank accounts that kept the war going.

President Obama signs bill to send military advisers to assist in the war against Joseph Kony in 2010. (Source: enoughproject.org)

Each party to the conflict—the rebels and the Ugandan military—terrorized the civilian population, displacing more young boys and girls and the cycle continued. Those who avoided recruitment or abduction had to continue to dodge both parties.

If either rebels or soldiers encountered civilians, they forced them to pledge allegiance to their cause. If they mixed up a rebel and soldier—something that was very easy to do in the dark, and because both parties to the conflict wore similar uniforms, they were accused of being traitors and punished. It was perhaps no surprise then that so many young men and women who did escape the rebels found it difficult to integrate within communities that had been afflicted and divided by more than two decades of violence. This extends to the children born in the rebel group.

Consider the reflections of one mother on how community members treat the child she gave birth to in captivity below: “He is called Kony even from home. They don’t call him any other name. They always call him Kony. They say that his mind is like Kony. They say that he acts like Kony in every way and that people should just wait and see because the boy will be a general like his father.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Otim Tonny was born in 1990 in Gulu, located in northern Uganda. He grew up witnessing the atrocities of the Lords Resistance Army rebels. He spends most of his time campaigning for peace and the abolition of militarism. Otim can be reached at [email protected].

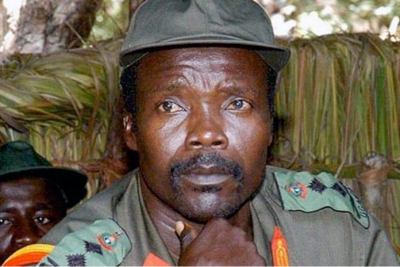

Featured image: Joseph Kony in the bush. (Source: observer.ug)