Photo Essay from India’s Victims of Urban Development: Life In Pieces For Delhi’s Displaced Community

Urban development and gentrification have a dark side. Not only are buildings being replaced, but so are people and their families and communities. Entire communities are either directly forced to move by the authorities or development companies or indirectly through increased property taxes, increased utility prices, or by the deliberate suffocation of their livelihoods. Although every case is not the same, the process generally targets the socio-economically less affluent inhabitants of a city and in many instances destroys the community economy and leads to destitution. This is why gentrification has even been called a form of “class warfare” by some of its critics.

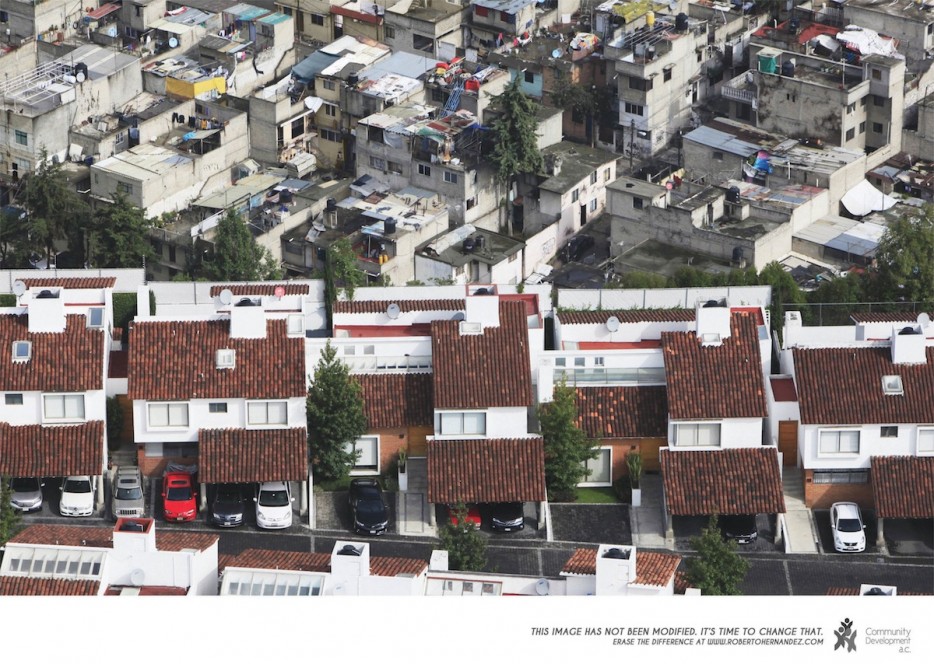

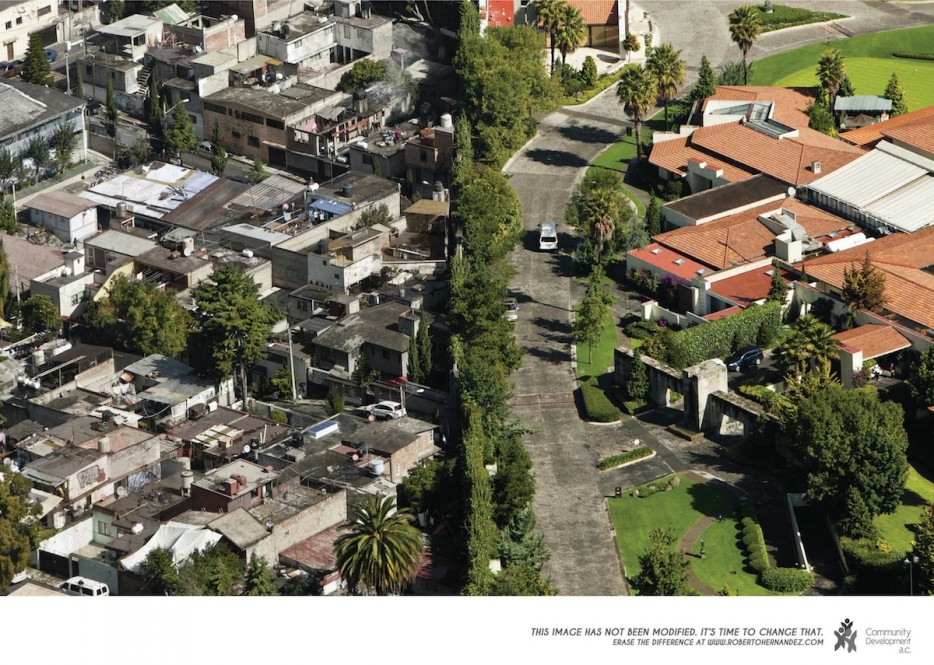

The poorer members of the city are being visually erased. They are literally hidden from sight. This is also part of the process of slowly marginalizing the poor by eroding their participation in public affairs and by erasing them from public view. When this happens, fighting poverty and helping the poor becomes less of a priority for city officials, no longer becoming a burning public issue.

In many cases physical violence and threats are used to displace these communities. Opting out of lengthening the process of eviction by taking advantage of the cheap materials the settlers use to build their homes, in many cases developers burn down the settlements of these people using fires and then make it look like the displacing fire or fires were an accident. Not only are properties and businesses lost in many of these fires, vulnerable people — such as the sick, handicap, elderly, and children — and animals die.

The story is the same in many parts of the world, from Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe to East Africa and Latin America, where people and communities are being alienated from their own urban landscape. In the interest of raising awareness about the conditions of these people, Asia-Pacific Research presents this photographic essay about a New Delhi community that has been displaced by urban development and gentrification.

The three pictures on display before the photographic essay from India are photographs taken from Mexico and serve to invoke thought by contrasting affluent and poor communities.

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya, Asia-Pacific Research Editor, 22 July 2016.

“The bulldozers were running over our homes even without any prior notice. We all ran to save our belongings, only to find most of them destroyed,” says Geetha, a former iron carver who is now working as a maid in homes nearby. She belongs to Gadia Lohar community, which seeks its origins from Rajasthan and finds its existence in history for it’s allegiance to a Rajput ruler, Maharana Pratap. In 2009, the state government decided to demolish their settlement, located ahead of the Tyagaraj Stadium in South Delhi during a ‘beautification spree’ just before the Delhi Commonwealth Games (CWG) 2010.

The Delhi High Court’s judgement in 2010 directed the authorities to plan a proper rehabilitation policy for the victims within 4 months of the demolishment. More than 6 years have passed but the rehabilitation is yet to be provided. The previous settlement of the community was at the roadside where it was easier for them to find customers. “My father used to earn around Rs. 400-500 daily. Now it’s not even Rs. 150, including the earnings of both of us.” says Kuldeep (26), who dropped from college 6 years ago to help his father in overcoming the financial crisis of the family.

A 2011 report from Housing and Land Rights Network suggests that more than 2,50,000 people were virtually displaced just before the CWG 2010 in Delhi. “How can they destroy our homes and call it a nation-building? How can they take our homes away just like that?” asks Gagan Singh (33), a former blacksmith, who now works as a contractual labourer. The community is currently based in a temporary settlement in a marginalized and deprived state.

Geetha (35), a mother of 2 children, used to work as an iron carver before her community was forced to leave their settlement in 2009. Now she is working as a maid in nearby houses.

Rohit Sisodia (32), along with her wife, Sunita (30) and two children. His occupation as a blacksmith suffered a lot after the demolishment.” No one comes here, away from the road to this settlement for getting their job done.They usually hire roadside blacksmiths,” says Rohit.

Iron tools kept in one of the Blacksmith’s shops for sale.

Gagan Singh (33), with his daughter, Medha (12). He returned home after 6 months from Jodhpur. Compelled to leave his traditional occupation of blacksmith due to the financial problems, he is now working there as a contractual labourer.

Mishtha (31), Gagan’s wife.

Worshipping place along with a traditional ‘Hukka’. There used to be a temple in the previous settlement which was demolished in 2009. From then onwards the community has made this place their worshipping spot.

The living conditions in these settlements are tough. Usually, a family of 6-7 people lives in a single room.

Ramesh Singh (55), is jobless for years. Suffering from the pulmonary Tuberculosis, he is not able to treat himself in any of the government hospitals as most of his official papers were lost during the demolishment.

Vicky Chauhan (36), a blacksmith standing in his shop. He is hardly able to earn enough through the profession which he perceives as an art after he was forced to leave his roadside shop during the demolishment in 2009.

Mukundilal Chauhan (62), is one of the eldest members of the settlement. He is the one who is leading the fight for his community’s rights on various platforms.

Radha, doing her household chores.

Even the temporary settlement is in danger of being evacuated since the Delhi Metro construction is getting intense in the area.

Vishank Singh is a New Delhi-based blogger/photojournalist who is currently pursuing his Masters in Convergent Journalism from AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia.