Philosophy Against the “Market Model of Education”

A comment on Howard Woodhouse’s Critical Reflections on Teacher Education: Why Future Teachers Need Educational Philosophy

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Howard Woodhouse, professor of history and philosophy of education at the University of Saskatchewan, is the author of a remarkable study published in 2009 by McGill-Queen’s University Press: Selling Out: Academic Freedom and the Corporate Market. In that opus, he demonstrated how, in the context of the advent of the economic and political ideology known as neoliberalism, and despite considerable faculty opposition, the “market model of education” has been imposed on universities in Canada and the Western world in general.

This process was triggered in two ways by most governments’ systematic underfunding of higher education in the name of “fiscal responsibility”.

First, this close-fistedness made universities increasingly dependent on corporate largesse and therefore responsive to corporate demands, thus curtailing academic freedom and undermining the autonomy of universities. (Wealthy donors have indeed not hesitated to block publication of articles and veto academic appointments, for example at the University of Toronto.)

Second, it forced institutions of higher learning to morph into businesses, “selling” education in the open “market”, competing with other institutions for students who can afford the rising tuition fees. This obviously lowers the quality of education, downgrading students to the status of “educational consumers” and turning academic degrees into commodities, similar to McDonald hamburgers, whose price varies as it depends on the purchasing power of the targeted consumers. The market model of higher education also reproduces, and even increases, social inequality, as a higher education becomes more and more expensive and therefore the privilege of a wealthy minority.

Inspired by the ideas of pioneers in the field of education, such as Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, and Paolo Freire, Woodhouse argues convincingly that education, including higher education, should not be made to conform to the “market model” or “corporate model”. The main reason for that is that the logic of the market is entirely different from that of education, that the two have incompatible goals. The market’s objective is the private accumulation of wealth, primarily the already gargantuan wealth of banks and corporations and the “one percent” in general, while education is about producing, and sharing, knowledge for the benefit of all. In other words, as Woodhouse puts it: “teaching and learning have a value beyond monetary reward”. The Canadian philosopher of education thus challenged what has become the dominant paradigm with respect to higher education, that “the market model is the only way forward”. He argued that governments have a responsibility to fund universities, making it possible for them to become again what they are supposed to be, namely, “the only places in society where the critical search for knowledge takes precedence”.

In an equally engrossing book published in the spring of this year by Routledge in New York, Critical Reflections on Teacher Education: Why Future Teachers Need Educational Philosophy, Woodhouse has turned his attention to primary and secondary education and teacher training not only in Canada, but also in the US and the UK. He observes that at this level too, education has been forced to conform to the market model, with schools increasingly becoming businesses and teachers as well as administrators morphing into “managers of small businesses”, providing young people with the kind of training deemed necessary for them to find a job and for the corporations and entrepreneurs who will employ them “to compete in the global market”. As in the case of higher education, what is prioritized is private material gain, normally in the form of money, whether for the students in their future career or for their future employers. What students learn, and what educators are required to teach, are the skills and knowledge that meet this overriding goal.

However, education at the primary and secondary levels should not be exclusively a for-profit enterprise, since it is capable of producing knowledge that can be shared for the common good. Rather than promoting the goal of “amassing private wealth,” education has the power to strengthen what Woodhouse calls the “goods of the civil commons”, namely those “life goods” available regardless of the ability to pay, such as clean air and water, universal health care, public libraries, and public broadcasting. In other words, education should be about teaching “human beings to live in ways that sustain the lives of all, including the earth and other species”.

As Woodhouse writes, echoing the late Brazilian specialist in the field of education, Paulo Freire, a system of education that adopts such a mission is much more likely to encourage “organic” and “creative” growth in young people who are “inherently curious and active creatures capable of independent, critical thought” and a “desire to know”, thus making education a “joyful mental adventure”. Conversely, Freire denigrated what he called the “banking approach” to education, whereby “all-knowing teachers”, acting on behalf of “an educational machine”, fill the “empty vessels” that happen to be the minds of children, with knowledge deemed to be useful by the current powers that be, useful, that is, for the purpose of “what the market designates as value”: making money.

Obviously, a Freirean alternative approach to education would require teachers capable of inspiring and guiding young people, and this brings Woodhouse to the topic of teacher education. As he sees it, teachers would benefit from studying, and should be enabled to teach, a discipline for which there is currently little or no room, namely philosophy as a process of inquiry about matters of everyday life.

Philosophy in this sense is above all about critical thinking, posing questions about human relationships, and engaging students in their capacity to reason about entrenched ideas, for example how the market may be undermining the earth’s capacity to sustain a wide diversity of species. Teachers should be able to introduce children to elementary principles of “philosophical reasoning”, teaching them not so much “what to think” but “how to think”, and helping them to understand or — to use Freirean terminology — “name” the world. Well established practices along these lines, known as “Philosophy for Children” (PforC), “bringing teachers and children together to discuss things that matter” so as to respect the views of others, have proved to be quite successful.

Teaching philosophy to children, then, means teaching them to think critically, and Woodhouse explains that this can be done in a variety of ways within the established curriculum. “Story-telling, dancing, drawing, music-making, writing, and science” can be useful for the purpose of stimulating “philosophical dialogue” in the sense of “use of imagination, questioning, dialogue, self-criticism, [and] respect [for] differences of opinion”. Such Freirean “praxis” can enable young people to deal with issues such as “racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression” and with the huge problems that afflict our society and the world in general, including the climate crisis.

In Canada and the US, unlocking young people’s potential for philosophical thinking should also involve exposing them to traditional indigenous thinking, especially with respect to the importance of land and other forms of the commons, solidarity with other living beings, and, last but not least, the crisis of climate change and environmental degradation, for whose gravity it can provide “an understanding that builds upon hope rather than despair”. Indigenous “two-eyed seeing” can and should indeed be used “in conjunction with Western science” to educate students about the climate crisis, since the two share much “common ground”.

The title of Howard Woodhouse’s stimulating book is “Critical Reflections on Teacher Education”, and its subtitle is “Why Future Teachers Need Educational philosophy”. However, it is hoped that this compact opus will be read not only by future educators: despite the dismissive way in which philosophy is treated in the dominant market model of education, we can all learn a lot from the critical reflections offered by this remarkable philosopher of education.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Jacques Pauwels is a Belgian-born Canadian historian. He is the author of The Great Class War of 1914-1918 (2016). His articles appear regularly on the Global Research website.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

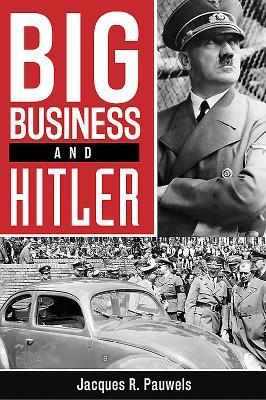

Big Business and Hitler

Big Business and Hitler

Author: Jacques R. Pauwels

ISBN: 9781459409873, 1459409876

Published: October 31, 2017

Publisher: James Lorimer & Company

For big business in Germany and around the world, Hitler and his National Socialist party were good news. Business was bad in the 1930s, and for multinational corporations Germany was a bright spot in a world suffering from the Great Depression. As Jacques R. Pauwels explains in this book, corporations were delighted with the profits that came from re-arming Germany, and then supplying both sides of the Second World War.

Recent historical research in Germany has laid bare the links between Hitler’s regime and big German firms. Scholars have now also documented the role of American firms — General Motors, IBM, Standard Oil, Ford, and many others — whose German subsidiaries eagerly sold equipment, weapons, and fuel needed for the German war machine. A key roadblock to America’s late entry into the Second World War was behind-the-scenes pressure from US corporations seeking to protect their profitable business selling to both sides.

Basing his work on the recent findings of scholars in many European countries and the US, Pauwels explains how Hitler gained and held the support of powerful business interests who found the well-liked oneparty fascist government, ready and willing to protect the property and profits of big business. He documents the role of the many multinationals in business today who supported Hitler and gained from the Nazi government’s horrendous measures.