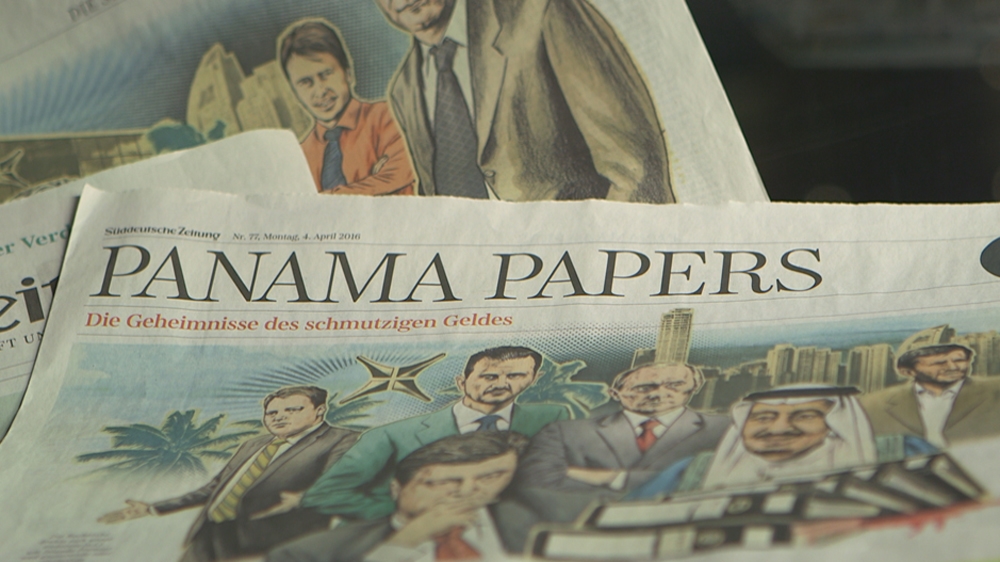

Panama Papers, The Secret of Dirty Money

Media Coverage of The Panama Papers Scandal

Throw them into the bay, or throw them into jail? Those were two possible replies to a poll set up by a user on Twitter. He wanted to know how to deal with “treacherous journalists” – the journalists in question were reporters working for the Panamanian daily newspaper La Prensa. The paper’s newsroom lies just 7.2 miles away from the offices of Mossack Fonseca, the law firm which plays the central role in the largest data-leak in history. The small state in Central America became eponymous for the scandals disclosed in the international research project Panama Papers – and many blamed La Prensa’s investigative journalists for this bad publicity. The majority of the participants in the twitter-poll demanded: Throw them into jail.

Bodyguards were still protecting the papers editors months after the stories had been published.

“This story was extremely personal for us. It involved many of our close friends, some of whom are no longer close friends”, said subdirector Rita Vásquez, “That is the price we knew we had to pay going into the project.”

A year has passed since the first stories on the Panama Papers appeared. Since then SZ, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and their media associates have published about 5000 articles, radio and television pieces. 400 journalists from 80 countries collaborated on the leak. Though they won many coveted Journalism Awards, they also had to suffer because of their work. The situation in Germany was comfortable in comparison; the team consisting of journalists from the public broadcasters WDR and NDR as well as members of SZ had to face increased security measures following the publication of Panama Papers. But for colleagues from other countries, things got a lot more risky. A Ukrainian reporter left his home country and didn’t come back until after the publication. Others were denounced in public or received threatening phone calls. In Tunisia the website of a media partner was hacked, a reporter in Venezuela was sacked. And some journalists were hounded by their own government. A brief overview:

“You put my face on the front page, have you no shame?”

In Turkey a newspaper received a death threat simply for mentioning a name included in the Panama Papers. On a Friday afternoon at the end of June 2016 the telephone rang in the offices of the Turkish paper Cumhuriyet. A male voice said:

“You put my face on the front page, have you no shame? I will fight you (…) You sons of bitches, don’t make a killer out of me.”

The caller was apparently Mehmet Cengiz, a Turkish entrepreneur. He and five other people were on the front page of that day’s edition, headshot and caption. They appeared in the leaked data. To interpret Cengiz’s call as a death threat seems plausible, maybe even necessary.

“Other protagonists of our stories sue us, but he didn’t”, says someone who works for the paper.

Cumhuriyet is one of the last remaining Turkish newspapers that is critical of the government. When the paper ran articles on the Panama Papers, many Turkish news sites picked them up. The government then had the uncomfortable websites blocked with court orders.

Keung Kowk-yuen was senior editor at the daily paper Ming Pao in Hong Kong. But just hours after publishing a story from the Panama Papers, he was told to clear his desk. The official statement said the reason for firing Keung Kowk-yuen was that the newspaper needed to save money.

“We can’t prove a direct link between the publication of the Panama Papers and his being fired, but attempts to intimidate the free press are very common”, says Benjamin Ismaïl, Asia expert for the journalist organization “Reporters Without Borders”.

Finland has ranked first in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index since 2010. So when the Finnish TV-journalist Minna Knus-Galán had to pick up a letter from the post office, she thought nothing of it. The 49-year-old works for the TV broadcaster Yle. Weeks prior to this day the TV broadcaster had made public the offshore dealings of Finnish businessmen and lawyers. The letter that Knus-Galán now received had been sent by the Finnish tax authorities: It demanded that Knus-Galán hand over the leaked data, so that the tax authorities would be able to run their own investigation.

“I was shocked and it felt unreal”, says Knus-Galán.

A politician from the conservative party even publicly accused the TV broadcaster of protecting tax evaders. The TV station also received mail from the tax authorities. Since then a Finnish court has been on the case: If the tax office wins it would soon be able to get its hands on the material from the leak.

“I see it as a way of the authorities to show efficiency, but they didn’t realize they were treading on press freedom and protection of source”, says Knus-Galán.

Watch Johannes Kr Kristjansson’s short video here.

Kristjansson nearly won the title “Icelander of the year” in 2016

Kristjansson nearly won the title “Icelander of the year” in 2016

There was one Panama Papers related media appearance in particular that got a lot of attention: Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, then prime minister of Iceland, was interviewed by the TV journalist Jóhannes Kristjansson. When Kristjansson asked the Prime Minister about his offshore dealings on camera, the politician began to stutter and abruptly ended the interview. The video spread around the world, Gunnlaugson stepped down a few months later. The reporter Jóhannes Kristjansson himself became a national celebrity, but not everyone has been supportive, he has also been confronted with a lot of criticism. He received letters, was insulted on the phone and yelled at in a grocery store:

“Are you happy now? You should be ashamed of yourself!”.

“To be a figure of public interest has more negative aspects than positive ones”, says Kristjansson, “but I would do it all again, no question.”

Kristjansson nearly won the title “Icelander of the year” in 2016. He came a close second to a team of paramedics in an online-poll. By the way: the third place went to Kristjansson’s adversary, the ex-Prime Minister Gunnlaugsson.

Translation: Thomas Salter