Pan-African Struggles Against Colonialism and the First Imperialist War, 1876-1919

From the decline of the Triangular Trade to the rapacious extraction of mineral resources and labor exploitation, Africans have organized and revolted against western domination

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Big Tech’s Effort to Silence Truth-tellers: Global Research Online Referral Campaign

***

Beginning in 1876, the monarchy in Belgium initiated a massive campaign to fully conquer the Congo where tremendous wealth existed in natural resources and labor power.

King Leopold I pursued the riches and workforce in Congo as a private enterprise where agents of the monarchy and other transnational corporations functioned as a de facto regime.

Over the next 32 years until 1908 when the colonial administration in Brussels took over the national oppressive and exploitative system in Congo, several reports indicate that up to ten million Africans were killed in the territories claimed by Belgium.

Several years after the Belgian intervention in Congo during 1884-85, the Berlin West Africa Conference was held in Germany which carved up the continent as spheres of interests for the imperialist powers.

Nonetheless, in the so-called Belgian Congo, Africans from various regions of the country resisted the horrendous methods of domination and forced labor. According to Calvin C. Kolar in his review of the literature on the efforts by the people to repel colonial rule noted that:

“A Force Publique officer reported, ‘I expect a general uprising…the motive is always the same, the natives are tired of the existing regime transport work, rubber collection, furnishing [food] for whites and black…For three months I have been fighting, with ten days rest…Yet I cannot say I have subjugated the people. They prefer to fight or die…What can I do?’ These revolts by the Mongo people highlighted the fact that revolts were not constrained to the Kasai region. Reacting to various pressures, violent resistance was widespread throughout the Congo.”

These developments were by no means isolated incidents. Africans resisted the onslaught of classical colonialism which resulted in the reported deaths of millions. From the late 19th century through the period of World War I, there were several rebellions and organized wars of resistance in the areas now known as Zimbabwe and Malawi, then controlled by Britain, along with Southwest Africa and Tanganyika under German domination.

The attempts to conquer Mashonaland and Matabeleland, now known as Zimbabwe, by the British military forces prompted the First Chimurenga (war of resistance). Africans fought a series of battles over a two-year period (1896-97) against the British.

Due to the lack of sophisticated weapons in abundance, the people of Mashonaland and Matabeleland were eventually defeated militarily and brought under colonial domination. See this.

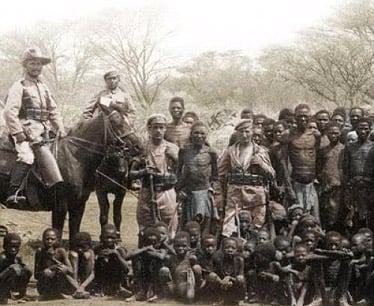

Later between 1904-1907, the Herero and Nama people of Southwest Africa, now known as Namibia, waged a resistance war against German colonialism. In retaliation for their resistance, the German imperialists systematically relocated and slaughtered 80 percent of the Namibian people. See this.

Also under German control, the colony of Tanganyika experienced a war of resistance popularly referred to as the Maji Maji Revolt of 1905-7. Africans in Tanganyika objected to the theft of their land, the paying of taxes to the colonialists while being subjected to forced labor in the production of agricultural products. (See this)

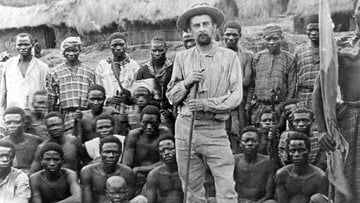

Image: Belgian colonialism in Congo

These events in Southern and Eastern Africa are highlighted to emphasize that African people responded in similar ways to the rise of colonialism during the 19th and early 20th centuries across the continent. The atrocities committed by the Belgian, British and German colonialists have been well documented by numerous journalists and historians during this period and in subsequent years.

The military phase of the struggle against imperialism in Africa was paralleled by the formation of mass organizations and conferences throughout the world. This process of opposition to European domination was a combined political, cultural and military effort to bring about the eventual independence of these territories and colonial states.

Colonialism in Africa and the Movements Against Racism

On July 23-25, the First Pan-African Conference was held in London, England just prior to the Paris Exposition. The gathering was attended by Africans and people of African descent largely from the British colonies and other English-speaking territories.

This meeting followed the Chicago Columbian Exposition and the Congress on Africa in 1893 where African American leaders such as anti-slavery organizer, women’s suffrage advocate and diplomat Frederick Douglass along with Ida B. Wells, who had built an international reputation as a journalist and an outspoken critic of the United States legal system for its refusal to prosecute mobs and law-enforcement personnel for carrying out thousands of lynchings in the South, utilized Douglass’ links with the Haitian government to distribute thousands of pamphlets exposing the actual conditions of Black people during this period. Wells’ work in defense of the security and rights of African Americans played an instrumental role in the launching of the African American women’s movement which came into fruition during the late 1890s and early 1900s. (See this)

The 1900 Pan-African Conference was described by the following source in this way:

“Speakers over the three days addressed a variety of aspects of racial discrimination. Among the papers delivered were ‘Conditions Favoring a High Standard of African Humanity’ (C. W. French of St. Kitts), ‘The Preservation of Racial Equality’ (Anna H. Jones, from Kansas), ‘The Necessary Concord to be Established between Native Races and European Colonists’ (Benito Sylvain, Haitian aide-de-camp to the Ethiopian emperor), ‘The Negro Problem in America’ (Anna J. Cooper, from Washington), ‘The Progress of our People’ (John E. Quinlan of St. Lucia) and ‘Africa, the Sphinx of History, in the Light of Unsolved Problems’ (D. E. Tobias from the USA).

By 1912, Duse Muhammad Ali from Egypt, founded the African Times and Orient Review in London. The newspaper published articles in opposition to colonialism in Africa and Asia.

People such as Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association-African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) in 1914 worked at the African Times and Orient Review prior to his emergence as world leader. In 1916 Garvey re-located to the U.S. and by the early 1920s, the UNIA-ACL had grown to an international movement with chapters around the U.S., the Caribbean, South America, Europe and in some regions of the African continent. (See this)

Consequently, leading up to the beginning of World War I, there were many instances of political and military resistance to imperialism on the part of African people on the continent and within the Diaspora. The First imperialist war from 1914-1918 led to an intensification of the struggle to end institutional racism and colonialism.

African Resistance to World War I

One of the earliest rebellions against the First Imperialist War took place in the British colony of Nyasaland, which is modern-day Malawi in early 1915. The rebellion was led by John Chilembwe, a U.S.-trained Baptist minister and educator who sought to prevent Africans from being recruited into the war effort.

There were battles on the African continent between German and British imperialist forces over the control of territories. Chilembwe protested the conscription of Africans into the British military for the purpose of fighting the Germans.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in a publication said of the Nyasaland Revolt:

“John Chilembwe’s rising was precipitated by the enlistment of Nyasas and their large death toll in the first weeks of the war in battle with the Germans. In his memorable censored letter to the Nyasaland Times of 26 November 1914 he protested ‘We understand that we have been invited to shed our innocent blood in this world’s war … we are imposed upon more than any other nationality under the sun’.” (See this)

John McCracken in his book entitled “A History of Malawi, 1859-1966, the author said of the Nyasaland Revolt:

“Within a fortnight the revolt had been suppressed. Three Europeans had died; two had been severely wounded, 36 convicted rebels had been executed, many others had been killed by the security forces. ‘For a rebellion against foreign rule, it had been, on the face of it, singularly ineffective’ noted Shepperson and Price in their authoritative account of the rising. Yet, as they also commented, the importance of the rising was far greater than its immediate, quantifiable, impact. A leading historian has claimed that this was the only significant rebellion in the whole of Africa to be inspired by Christianity prior to the First World War. It provided Malawi with its one unproblematic hero, John Chilembwe; his image is now depicted on Malawian bank notes.”

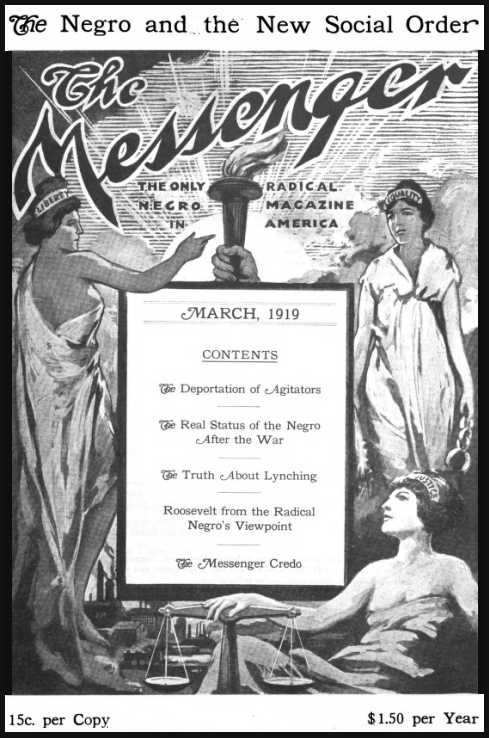

In the U.S., A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owens, editors of the Messenger newspaper, which was affiliated with the Socialist Party during World War I, were charged with violating the Espionage Act of 1917. The paper opposed African American involvement in the imperialist war. (See this)

Although Randolph and Owens were arrested at a Socialist Party rally in Cleveland on August 4, 1918, and brought into court for espionage, the judge refused to sentence them because he did not believe that the two young African Americans could have written and edited the Messenger. He believed that they were mere agents of the Socialists and ordered them to leave the city.

Randolph and Owens were only two of the estimated 10,000 people who were arrested for opposing the war, many of whom were socialists. Others were deported for advocating peace and social change. The repression initiated by the Department of Justice during the war continued under Attorney General W. Mitchell Palmer when in 1919-20, 6,000 people were unlawfully detained in over 30 cities.

After the conclusion of the First Imperialist War, Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois convened the Pan-African Congress in Paris. This gathering in 1919 coincided with the escalation of racist violence inside the U.S. along with anti-colonial rebellions in Egypt. (See this and this)

As the 1920s and 1930s would reveal, the struggle against national oppression, institutional racism and imperialism escalated. By the beginning of the Second Imperialist War, the historical stage was set for the advent of the independence and civil rights movements which swept the entire African world.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

All images in this article are from the author