This is a translation of a keynote speech delivered by Muto Ichiyo at a peace conference held in Hiroshima Aug. 4-5, 2015, marking the 70th anniversary of Japan’s defeat in the war. The conference, attended by 300 local and national activists, sought to shed new light on the war responsibility of imperial Japan and US responsibility for the atomic bombings. The text has been revised and updated for the Asia-Pacific Journal.

The speech was made during a summer of intense public protests over security legislation then being debated in the Japanese Diet. Despite opinion polls that showed the legislation to be exceedingly unpopular, the laws were rammed through the Diet on September 19, 2015. These contentious issues have now entered a new stage, with the drive to revise Japan’s peace constitution at the center of the Upper House election scheduled for July 10. Muto’s speech analyzes the issues that lie behind the present contest in light of the complex dynamics of Japan’s postwar politics.

John Junkerman, Translator, 1 July 2016.

The struggle over reshaping postwar Japan entered a new phase on March 2, 2016, when Prime Minister Abe Shinzo declared at an Upper House Budget Committee hearing that he was committed to revising the constitution within his term of office, that is, by September 2018. Changing the postwar regime by fundamentally revising the present pacifist constitution has been Abe’s goal since he returned to power in 2012, but for some time he had avoided clearly stating his plan, knowing that the majority of voters oppose constitutional revision.

In the three elections that have taken place during his administration (including the one that returned him to power in 2012), Abe has trumpeted “Abenomics,” ultra-lax monetary and fiscal policies aimed at extracting the economy from deflation by stimulating consumer spending, as his main political program. However, while campaigning on its economic policies, since the elections the Abe administration has pressed forward with changes in laws, systems, and institutions to heighten Japan’s defense posture and undermine the constraints on Japan’s armed forces imposed by Japan’s constitution.

For example, after the LDP scored a victory in the 2013 Upper House election, Abe significantly increased defense spending and pushed through the controversial State Secrets Act in December of that year. The most blatant action in this direction was the Cabinet’s decision in July 2014 to reverse a long-standing interpretation of the constitution; for decades the Cabinet Legislative Bureau had held that Article 9 of the constitution prohibited the Japanese Self-Defense Forces from exercising the right of collective self-defense. Reversing this interpretation meant that Japan could come to the aid of an ally under attack, even if Japan itself was not attacked. In line with this decision, a set of laws called the “security legislation” was drawn up and presented to the Diet in May 2015.

This called forth strong popular protest, which mounted over the summer into the largest demonstrations in Japan since the 1970s. Thousands of citizens mobilized spontaneously, joined by peace and other movement groups from earlier decades. After many years of absence, students joined the rallies in front of the Diet, demonstrating in ways markedly different from those of the traditional left. Each individual speaker delivered personal messages, telling her or his particular reasons for confronting Abe and his power grab. In place of the standard shouted slogans of past demonstrations, their rhythmic, rap-influenced call and response lent spirit and buoyancy to the rallies.

One of the developments that spurred the demonstrations was the testimony in the Diet by three leading constitutional scholars in early June 2015, unanimously advising that the proposed security legislation was unconstitutional. This delivered a bombshell to the LDP, as two of the scholars were known for their conservative views, and one was invited to the hearing by the LDP itself. Subsequent surveys of constitutional scholars found a nearly unanimous consensus that the legislation was unconstitutional. Until that point, the Diet deliberations had focused on the various individual provisions of the legislation, but their testimony shifted the focus to the unconstitutionality of the entire package of legislation.

This added momentum to the keen sense of crisis already motivating the public to action, the perception that the security legislation would change Japan into a country that would fight wars. This alarmed young people. In addition to the issue of unconstitutionality, the issue of peace—and whether there would be a military draft—loomed large in their eyes.

Public anger at what came to be called Abe’s “war legislation” heightened and more and more people joined the demonstrations at the Diet. On August 30, more than 100,000 occupied the broad avenue in front of the Diet, overwhelming steel barricades set up by the riot police. The demonstrations became an everyday affair, involving ever new groups of people.

The Diet deliberations on the bill were a sham as Abe and his ministers refused to seriously answer opposition interpellators. On September 17, the bill was forced through an Upper House committee and then passed on September 19 by the full house, where the LDP-Komeito coalition government holds a majority.

The Abe administration used this victory to advance two major policy positions. The first is to promote the doctrine of deterrence. Arguing that the international security environment has drastically changed, specifically pointing to China and the danger it poses, they argue that it is necessary to strengthen the Japan-US alliance to counter the threat. Second, they argue that, if the security legislation violates the constitution, then the constitution should be changed. In the upcoming Upper House election, Abe has set an explicit goal of obtaining a two-thirds majority of seats for the LDP and its allies, which will allow them to initiate the revision of the constitution.

So, what is at the heart of these issues? What is the Abe administration attempting to accomplish?

A Semi-Coup d’état in Process

The Abe administration is the first postwar administration to call for and attempt to carry out a “change of regime.” In the 1980s, PM Nakasone Yasuhiro called for “settling the accounts of postwar politics,” which closely resembles “breaking with the postwar regime,” the slogan of the first Abe Cabinet (2006–07). In Nakasone’s case, the slogan was mere rhetoric. Abe, however, may be able to realize his goals.

What he has been carrying out is a form of coup d’état. The evidence for this is that he has placed men and women under his command in some of the most important positions in Japanese society. In the United States, when the president changes, the personnel in Washington change dramatically. This has been far less true in Japan, but Abe moved quickly to consolidate his hold on government after he returned to power in 2012. He placed people who will follow his lead in positions such as the governor of the Bank of Japan (to do his bidding with his Abenomics agenda); the director-general of the Cabinet Legislative Bureau (to revise the official interpretation of the constitution); and the chairman of NHK (to ensure more favorable political coverage). The character of these appointments was typified by Saitama University emeritus professor Hasegawa Michiko, who was installed on the NHK Board of Governors. Hasegawa has written in the journal of the ultra-right Nippon Kaigi organization:

Depopulation might destroy Japan. It is often described as a disorder of advanced civilization but, looking around the world, there is something else involved here. It is the disease of feminism. Feminism is the activist movement of women who can’t abide the fact that they are women. Stated more concretely, raising children well, protecting the family, nurturing fine children, men and women marrying when they reach the proper age, and as a matter of course, having children after they marry. Feminism rejects all of this.

While calling for a “society where women shine,” Abe appointed someone who thinks this way to the NHK Board of Governors. The appointment required Diet approval, and it was questioned in the Upper House budget committee hearings on March 12, 2014. According to the Asahi Shimbun, “Abe responded, ‘She is one of the country’s leading philosophers, studying thought and philosophy and writing such books as Karagokoro: Nihon Seishin no Gyakusetsu [Chinese Heart: The Paradox of the Japanese Spirit].’” This is unbelievable. This notorious right-wing thinker is appointed to a key position at NHK. The first thing a coup d’état administration does is to occupy the controlling heights, especially asserting control over broadcasting. This is the Abe methodology, grabbing state power in what amounts to a virtual coup d’état.

Then comes the security legislation. It is evident to all that the laws are unconstitutional, but the administration tries to push them through with a logic that has no logic. To start with, “changing the regime” or “changing the system” would normally necessitate changing the constitution. The LDP drafted a revised constitution in April 2012, when it was out of power. The Abe administration has always promoted constitutional revision, and the first Abe Cabinet made moves in this direction, in 2007 revising the Fundamental Law on Education, the “constitution” of the educational system, to promote patriotic education. He also pushed through legislation to establish the framework for the public referendums that are necessary to ratify any changes to the constitution.

In September 2007, Abe left power, apparently ill, and the first Abe Cabinet ended in failure. Abe hoped to push for constitutional revision when he launched his second cabinet in December 2012, but he realized that he lacked the required two-thirds of the vote in the Upper House, and the prospects were not good for winning a majority in a national referendum to approve the amendments. So he first proposed changing Article 96 of the constitution, which requires two-thirds vote in both houses of the Diet to initiate an amendment; he aimed to lower the threshold to one-half of each house of the Diet to make it easier to enact the LDP’s amendments. This proposal was not only very unpopular, but was dismissed by constitutional scholars as a “backdoor” approach, and Abe abandoned it.

What the administration did instead, with the collective security legislation, was to effectively change the constitution without going through the formal process of revision. While in recent decades LDP-led governments have regularly revised the interpretation of the constitution to allow the dispatch of the SDF overseas (for UN peacekeeping operations and for support of the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq), this legislation represented a more fundamental change. Its passage constituted a “semi-coup d’état.” What would normally be possible only after revision of the constitution (a successful coup d’état) the Abe administration carried out under and in the name of the present constitution. They had to find a way to make an unconstitutional act fit the constitution. Somewhat ineffectually, LDP Vice President Komura Masahiko invoked the 1959 Supreme Court decision in the Sunagawa Incident (a ruling that US bases in Japan did not violate Article 9 of the constitution), an entirely farfetched rationale. The administration then argued that it understood the geostrategic reality Japan faces, and the necessity for collective self-defense, better than the nation’s constitutional scholars. But in the end, they simply used their parliamentary majorities to force through the legislation.

A Nonsensical Understanding of History

In July 2013, Vice PM Aso Taro said that constitutional revision should be carried out quietly, without a fuss. He suggested that Japan learn from the example of the Nazis who, having won an electoral victory under the Weimar Constitution, replaced it with a Nazi constitution without the German people noticing. This was a misreading of history, since the Nazis, rather than amend the constitution, instead used the Enabling Act to effectively suspend the constitution and grant Hitler emergency powers. But in any case Aso’s intention was to avoid a frontal assault on the constitution and use the weight of accumulated unconstitutional changes to make it easier to breach the walls preventing revision when the time came.

The Japanese situation is very different from the Nazi era. The Nazis came to power during the Great Depression when society had fallen into chaos; the Communist Party had grown via intense class struggle, and in that context the Nazis gained strength and took control of the Reichstag. It was a time of social upheaval. Today’s Japan is entirely different. To be sure, the LDP enjoys majority support, but these supporters think it is the LDP of old. The previous DPJ administrations were so ineffectual that the LDP was simply returned to power; people didn’t vote to endorse Abe’s scheme to gut the constitution. Therefore, in public opinion polls since the start of the administration, the Cabinet’s basic policies have never had majority support. An odd situation has prevailed, where support for basic policies has been far below 50%, while support for the Cabinet has been around 50% (though support fell below this level during the Diet deliberations on the security legislation). Thus, though the weakness of the opposition has enabled the LDP to win successive elections, the Abe administration’s social foundation is not at all solid, nor is it broad.

However, the Abe Cabinet has at its base a solid core of ultra-right organizations. A majority of the LDP Diet members (and quite a few from other parties) belong to Nippon Kaigi and/or are affiliated with other right-wing groups, constituting the so-called “Yasukuni faction.” One indication of the ideology of these groups is seen in the example of Tamogami Toshio, the ex-Chief of Staff of the Air Self-Defense Force. Tamogami was fired in 2008 after he won an essay contest by arguing that the Comintern caused the Manchurian Incident, that the Xi’an Incident that led to the anti-Japanese united front in China was a setup by Stalin, and other assertions that have as much credibility as warnings of UFO attacks. But PM Abe appeared at an “Evening in Thanks to Tamo-chan,” and delivered the following paean to Tamogami. “In every era there are people who have the courage to say, ‘This is wrong,’ and to sound the alarm for the world, sometimes risking their jobs, and sometimes risking their lives. It is on account of such people that the times move in the proper direction.” That’s the kind of ridiculous historical consciousness the prime minister has.

The slogans of the first Abe Cabinet were “Toward a Beautiful Japan” and “Breaking with the Postwar Regime.” Now the slogan is “Retake Japan.” The premise is that something has been lost. What is it? It is the essence of the Empire of Japan. To Abe, the “postwar” has been an extremely unfortunate era. The reason is that the honor of the glorious Japanese empire was denied and the Occupation imposed the constitution on Japan.

It is not only Abe who thinks this way; this thinking is fairly deeply rooted in postwar Japanese leadership long dominated by the LDP. In fact it is my contention that in the postwar Japanese state, the continuity of the Japanese empire was preserved, if surreptitiously, as a principle of the legitimacy of the state.

The Incompatibility between the Constitution and the United States

A state must be organized around certain legitimizing principles. The state is all mighty, so it can legally kill people. It can fight wars. When it fights a war, it can take people’s lives, and those who are sent to war die. In order to undertake these things, it is necessary for the state to have legitimizing principles. Unless the state has fundamental, legitimizing principles, it can hardly ask the people to risk their lives for the state. What were the legitimizing principles of the postwar Japanese state?

The United States has the Declaration of Independence as its legitimizing document. France has the Declaration of the Rights of Man from the time of the French Revolution. Sometimes the actual functioning of the state diverges from those fundamental principles; in these cases, the actions must be fudged or an excuse found to justify them. The legitimizing principle in the prewar Japanese empire was the sovereignty of the emperor. Everything that was done by the imperial state in his majesty’s name was legitimate and justified. The invasion of Ainu homelands, the annexation of the Ryukyu kingdom, the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars, the annexation of Korea, the invasion of China, the Great East Asia War—all of these were justified in the name of the emperor.

Japan surrendered in 1945, and the empire lost its legitimacy. The Occupation began, the constitution was created, and the postwar state was born. So, what provided legitimacy for the postwar state? First of all, the Constitution of Japan. This is the foundational law of the postwar state and the source of its legitimacy and justification. Or, it was supposed to be. However, in fact, not everything the Japanese state did could be justified and legitimized by the constitution. Why? Because of the presence of the US military throughout the postwar period. On the very day in September 1951 that the San Francisco Peace Treaty was signed at the Opera House, PM Yoshida Shigeru proceeded alone to the Presidio military base and signed the Security Treaty. The Peace Treaty stated that foreign military forces would withdraw within 90 days, but it included an exception for the Security Treaty, and US forces would remain in Japan for an indefinite time after its independence.

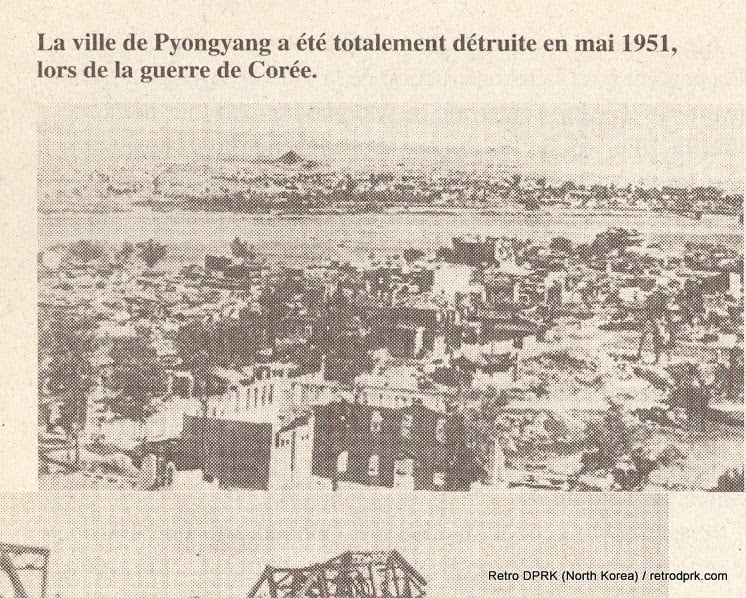

Even more significant, Japanese armed forces—proscribed by the constitution—were created by order of Douglas MacArthur, the supreme commander of the Occupation, over the heads of the Japanese Diet. This was in 1950, soon after the Korean War began, and they were called the National Police Reserve. The reserve force was intended to fill the vacuum that was created when most of the Allied forces stationed in Japan were shifted to the Korean Peninsula to engage in full-scale war. At this time, the term “indirect invasion” was coined. Normally, an invasion means a foreign army landing on the shores of a country, but if large-scale riots and disturbances in Japan were considered to have occurred through instigation or intervention by an outside power, they would be deemed an indirect invasion; and it was the National Police Reserve that was to deal with the “invasion.” Moreover, under the 1951 security treaty, US forces may be utilizedto put down such disturbances in Japan. As is clear from their origin, the postwar Japanese armed forces were, and have ever been, an alien entity in the Japanese state. From the start, they were a part of the US military system, and as they grew, they came to function as a part of the American strategic posture. They do so to this day.

There is a commitment to interoperability in the Japan-US defense guidelines, so since 1951 the US military and the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) have shared weapons and equipment, war plans, logistics, operational manuals, terminology, and communication and other systems. The body that exists as the Japanese military has been organically incorporated into and subordinated to the US military. In other words, the state power of the US has been internalized in the Japanese state. This means that the principle of United States hegemony has been integrated into the Japanese nation and plays a role as one of its legitimizing principles.

The Japanese Empire as a Third Principle

The conflict between the pacifist principles of Japan’s constitution and the American hegemonic principle has long been contested, for example in the anti-base movement in the 1950s. In this context, constitutional scholars such as Hoshino Yasusaburo pointed out that the constitution and the Security Treaty system exist in Japan as parallel, contradictory legal and ruling systems. This is clear when we look at postwar domestic developments in Japan. For example, Okinawa, which was under the control of a US military government, was separated from Japan in 1952 when the SF Peace Treaty came into effect. The military government of Okinawa made it a US military colony that fit into no category of international law.

An agreement was reportedly reached at the time of the SF Peace Treaty, whereby the US recognized Japan’s “residual” sovereignty in Okinawa. This was considered a victory for Japanese diplomacy. Some even argue that the emperor’s message, proposing that the US administer Okinawa indefinitely,1 helped win the acknowledgment of “residual” sovereignty (translated into Japanese as senzai shuken, or “latent sovereignty”).

We can see here an example of how the legitimizing principle of the US state—the principle of hegemony, of Pax Americana—became incorporated as a principle of the Japanese state. Through its latent sovereignty, the Japanese state retained control over Okinawa, while it remained in substance a military colony of the US. When Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, its status was one of an internal colony of Japan, while the concentration of US bases there ensured that it would continue to be a US military colony.

However, in postwar Japan, there is a third fundamental principle. This is something that has normally remained hidden. It is the manner in which the Empire of Japan survived within the postwar Japanese state. The most important vehicle for the survival of this legitimizing principle was the postwar emperor system.

The prewar and wartime emperor was not at all an ornament, but rather was the generalissimo who rode out from the palace in uniform on a white horse. A photograph of this scene was displayed on the walls of many homes. This man led his country in successive wars, his army was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions of people in Asia, and millions of his own soldiers and Japanese civilians died. Many of those soldiers starved to death. And he lost the war. Despite being the commander in chief of the war, after his government surrendered to the allies, he retained the title of emperor and continued to live in the Imperial Palace.

The logic of this was spelled out as early as 1942 by the Japan scholar and later US ambassador Edwin Reischauer, who advised the US government to exploit the emperor to maintain control after defeating Japan.2 The maintenance and exploitation of the emperor system was carefully prepared by the State Department and implemented by the Occupation. MacArthur was adept at using the emperor. The general issued solemn statements in the form of New Years messages and the like, but he seldom appeared in public. This was similar to the prewar emperor. MacArthur remained ensconced in the Occupation headquarters in central Tokyo. Instead, it was the emperor who was sent out on numerous tours through Japan, exposed to the public eye.

MacArthur made strenuous efforts to ensure that the emperor, far from being prosecuted or even forced to testify in the Tokyo war crimes trial, retained the throne. He promoted a constitution that removed the governing authority of the emperor, while preserving his status (in Article 1) as “the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people.” This was done rapidly so the draft would be ready before the Far Eastern Commission (which would have the authority to decide policies for the occupation of Japan) could be set up and issue a directive to prosecute the emperor. The draft constitution was comparatively democratic, with content that would not raise objections among the public in either the Soviet Union or the US. That constitution was adopted, so the postwar emperor system is often referred to as an American-made system.

Thus Emperor Hirohito, who had the highest responsibility for the war, was left unpunished and did not abdicate. The consequence of this was that it limited the punishment of those who acted under his orders and in his name. The entire responsibility for the war was shifted to General Tojo Hideki and the other Class-A war criminals, seven of whom were executed even though the emperor was their supreme commander. The emperor became a “symbol of peace,” credited not with waging the disastrous fifteen year war but with the surrender. The result was that, following the execution of the Class-A war criminals, with Hirohito remaining on the throne, the Japanese state could do no more to punish war responsibility.

Restoring the Honor of the Class-A War Criminals

In this fashion, a vessel was created to preserve and nurture the idea that the wartime actions of the empire were not wrong, and even that they were right. After the Occupation ended, the legitimizing principle of the prewar empire was clearly retained within the Japanese government. On May 1, 1952, immediately after Japan regained its independence on April 28, Attorney General Kimura Tokutaro issued a notice that stated that war criminals who had been put to death were not “executed” but instead had suffered “death during legal duty” (hōmushi).3 This is a term that was never used before or since. It was an official measure that restored honor by declaring that all of the war criminals who were put to death had not died as punishment for committing crimes. At the same time, the cause of death in the family registers of these individuals was changed from “execution” to “death during legal duty,” and the payment of war pension benefits was resumed. The San Francisco Peace Treaty includes a clause that states that Japan accepts the judgments of the war crimes trials. But immediately after the treaty came into effect, the honor of the Class-A war criminals was restored. Doing this in such short order indicates the existence of a strong state will. There is more. In 1952 and 1953, the Diet voted three times to approve the release of imprisoned war criminals. A few members of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and the Labor-Farmer Party were opposed, but the measures passed with nearly unanimous support, including from the Japan Socialist Party. A petition in support of releasing all imprisoned war criminals gathered 40 million signatures. During the Diet debate, one supporter of the release described all convicted war criminals as victims of the war.4 The grounds for demanding the release of war criminals was that the Tokyo trial represented victor’s justice, which is what the right wing still asserts today.

It is certainly true that the Tokyo trial was victor’s justice and lacking in fairness, but if that was the case, then Japan should have conducted proper trials of its own. In the war they initiated, the leaders of the Japanese empire committed crimes, not only against people in foreign countries but against their own people. Contemporaries should have said, “We’ll try them on our own.” If there were many flawed convictions among the B- and C-Class war criminals, then their own country should have held new trials and brought these to light. But the thinking during the Diet deliberations was that all of the war criminals were victims of the war, to be told, “Sorry for your hardship, welcome back.”

Thus postwar Japan created a sphere of immunity from responsibility. In this sphere, the thinking that the Empire of Japan had been right was kept alive within the postwar Japanese state, and this thinking was then put into action. The best evidence of this is in the Ministry of Education’s textbook authorization process. The ministry (now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, MEXT) has followed a policy of concealing, to the extent possible, the war crimes and horrifying actions committed by imperial Japan. As typified by the order to reword “invasion” as “advance,” the will of the state is transmitted to the schools. When this was exposed internationally, it developed into a diplomatic issue, the “Japanese textbook problem.”

In the field of foreign affairs, the Japanese government has always taken the position that the annexation of Korea was legitimate. The Tokyo trial had narrowed the timeframe for Japanese war crimes to after 1931, so the 1910 annexation was outside its scope. There was a risk involved in addressing the issue during the trial. The US and Japan had reached an understanding in 1905, the secret Taft-Katsura Agreement,5 that after the Russo-Japanese War ended, the US would recognize Japanese control over Korea, while Japan would recognize American control of the Philippines. This is one important reason why the trial did not address the annexation of Korea.

In this fashion, the principle of imperial continuity, which the new constitution ostensibly disavowed by making the emperor a “symbol,” was retained and implemented by the postwar state wherever possible. This indeed was a third principle of the postwar state, which could not be spoken about openly. But because it was a legitimizing principle of the state, every action the Empire of Japan had taken, from the seizure of Ainu lands and Ryukyu, through the invasion of China and the Pacific War could be treated as legitimate.

To repeat, it is my view that the postwar Japanese state is formed from these three legitimizing principles—the postwar constitution, American hegemony, and the continuity of imperial Japan. The three have continued to exist in a relationship of mutual incompatibility. The first and second are visible, while the existence of the third is usually denied or downplayed. None in fact was able to assert itself at the expense of the others. As a result, none of these three principles has been able to attain the status of the fundamental principle.

There is a need to consider the merits of the Japanese constitution, but what has made the principle of pacifism embodied in Article 9 function as an effective principle of the state and society is the strength of the movement from below. The state itself has not been able to properly use the principle of pacifism as a principle. The decision of the Tokyo District Court in the case of the Sunagawa Incident was that the Security Treaty violated Article 9 and was unconstitutional. At that moment, the Japanese state recognized the pacifist principle as the foundational principle of the state. However, immediately afterward, Supreme Court Justice Tanaka Kotaro (the presiding justice for the Sunagawa case) met with US Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II and then issued a baffling ruling declaring that the Security Treaty fell into the category of a “political act,” and therefore its constitutionality could not be judged through the process of “judicial determination.” With that, the Japanese state transformed the pacifist principle into a pseudo-principle.

Then, did American hegemony attain full status as a principle? No, it didn’t, because of the strong force of such movements as the anti-Security Treaty struggles of 1960 and 1970. The US hegemonic principle is “freedom,” which equated to anti-Communism. Japan did not become an anti-communist state the way Germany did immediately after the war; during the early postwar administration of Konrad Adenauer, for example, the slogan “better dead than red” gained currency. Thus, none of the three principles gained ascendancy, and the Japanese state saw to it that they coexisted reasonably well, using them each when it was appropriate. As a result, all three lost their qualification as fundamental principles.

It was the LDP that took best advantage of this situation, and was able to remain in power for decades. Standing in opposition to this was the so-called progressive forces. The largest of these, the JSP, had as its political base 4.5 million organized workers of the Sohyo labor federation. In addition were the JCP and a political bloc of progressive intellectuals. These formed the opposition to the LDP-led government. This postwar progressive force embraced the constitution’s pacifist principle as a principle, and forced the state to respect constitutional pacifism as a fundamental principle the state should adhere to. However, there was a major weakness. This force saw peace entirely from the perspective of domestic Japan. In their perception war was something that would attack peaceful Japan from the outside, and it was enough to avoid that. With this mode of thinking, all that mattered was peace within Japan, and the movement tended toward the conservative goal of maintaining peace, i.e., the status quo.

The Beheiren and Zenkyoto Movements

In the second half of the 1960s, a new movement emerged as distinct from the traditional left. Beheiren (the official English title is Japan “Peace for Vietnam” Committee; the literal translation is Citizen’s Coalition for Peace in Vietnam), Zenkyoto (All-Campus Joint Struggle Committee), and later, the women’s liberation movement came on the scene. Most visible were the intense street demonstrations where New Left sects clashed with the riot police and the Zenkyoto campus struggles that occupied and shut down universities. Meanwhile the struggles in Sanrizuka and Minamata spread their strong impact nationwide as local movements against environmental pollution and development, and Beheiren’s activities to help deserters from the US military gained attention. There was an eruption of every form of resistance, and they created an unexpectedly large and dynamic sphere of political activism.

The political movements of that era overturned what was considered common sense by earlier Japanese movements. Earlier movements were aimed at protecting something—protecting peace, which over time came to mean the status quo. In the context of rapid economic growth, the “peace” that represented resistance in 1960 shifted to the maintenance of the status quo. In contrast, the movements of the late 1960s pointed to the status quo itself as the problem: It came to be understood that Japan was already complicit in the American war in Vietnam, and that relationship had to be changed then and now. That was an essential characteristic of the new movement. And in the midst of it, the concept of fundamental principles of state and society was refined and enriched. I think we can see in this new movement process the crystallization of the concept of the right to live in peace (heiwa-teki seizon ken), integrating three elements in the constitution, namely, the pacifist statement in the preamble, renunciation of war and armed forces in Article 9, and the people’s right to life and the pursuit of happiness in Article 13.

I think we also need to take a look at changes in the underlying structure that sustained the workings of the postwar state. This is what amounts to the national territory-centered mode of capital accumulation of postwar Japanese capitalism. This economic structure underlay the LDP’s ability to rule more or less securely by manipulating the three otherwise incompatible legitimizing principles. The structure combined large-scale land development, siting industrial estates along the coastlines; the systemization of large enterprises and their small- and medium-sized subcontractors; the system of food control (price support for rice farmers); and pork-barrel politics using the national coffers, all of which were instrumental to achieving rapid economic growth. As long as this functioned well, politics sorted itself out. There was little need to politically mobilize citizens. The economy was the stand-in for politics.

This began to crumble in the late 1980s, as neoliberalism and globalization undermined this foundation. The economic cycle that was contained within Japan broke down, which in turn eroded the LDP’s political base. Meanwhile, privatization, especially of the national railways, began to rapidly undermine the base of public sector labor unions, and in 1989, the Sohyo confederation was absorbed by the corporate-oriented Rengo federation. This left the JSP without its main organizational support, and it fell into decline.

1995 was, in numerous ways, the beginning of the present era.

That year saw the advent of the Murayama Tomiichi Cabinet. The LDP, JSP, and the New Party Sakigake formed a strange-bedfellows coalition, with the LDP giving the premiership to JSP Chairman Murayama in order to cobble together a majority in the Diet, with the inclusion of the smaller Sakigake. It was a moment when two conflicting currents crossed paths. One was the emergence of wartime compensation claims, including those of “military comfort women,” which resulted in a succession of court cases. Within Japan, there was a growing tendency to acknowledge these claims, and a movement emerged calling for new inquiries into wartime victimization.

It was also around this time that rightwing forces seeking to justify imperial Japan began a simultaneous offensive on a number of fronts. Nippon Kaigi formed as a broad coalition of all the ultra-right forces. The Society for History Textbook Reform was launched, textbooks reflecting their nationalistic historical stance were produced, and an effort was begun to have the texts adopted by Japanese schools. This finally brought the third legitimizing principle—imperial continuity—to the fore, and with that principle at the core a full-fledged move was launched to revise the constitution and replace the postwar state with a state based on the principles they adhere to. Ten years later, Abe Shinzo, deeply identified with these rightist campaigns, formed his first cabinet. This rightist force does not actually have a strong base in the wider society. But during these years, the counter force on the left has grown weaker, both organizationally and philosophically. The impact of the collapse of socialism has been great, and no new vision for transforming society has been gained momentum. In that context, the right has taken advantage of the opportunity to fan the flames of xenophobia. Bookstores are flooded with anti-Chinese and anti-Korean books, ephemeral as they may be. This should not be taken lightly.

Abe’s Policies Could Destroy Japan-China Relations

One concern is that, as long as the Abe administration stands on the principle that the Japanese empire was legitimate, that could undermine the premise of Japan’s relations with China. As long as Abe embraces the idea that the Nanking massacre never happened, or that comfort women were simply prostitutes, that the Chinese war of resistance against Japan was a Comintern conspiracy—even if he sugarcoats these beliefs in his public declarations—he cannot build a stable relationship with China or South Korea. Politically, PM Abe will not say these things openly, but it is clear from his statements from the time the LDP was still out of power, that his true beliefs differ very little from those of Tamogami.

The foundations of the Japanese relationship with China were set in clear terms in the joint communique that established diplomatic relations in 1972. There it was stated that Japan, “keenly conscious of the responsibility for the serious damage that Japan caused in the past to the Chinese people through war, deeply reproaches itself.” If this statement is overturned, friendly relations with China become impossible.

Japanese officials say that they welcome top-level talks and the door is always open, but since PM Abe affirms Japan’s imperial past, meeting with him would mean giving China’s stamp of approval to those views, and China is not about to do that.

Even more to the point, Abe has developed and seeks to implement something like a global doctrine that makes relations with China impossible. Abe often says in his speeches, “I create my strategy by looking at a globe.” What kind of strategy? He proposes to organize an “arc of liberty and prosperity,” running from Europe through the Middle East, to India, Southeast Asia, and Japan, an alliance of countries with shared values led by Japan, advancing economic development and guaranteeing mutual security. This is clearly a China containment policy. It is virtually impossible to build friendly relations with China on that foundation.

When it comes to relations with the US, there’s no way the US will accept the stance that the Great East Asia War was legitimate. As a result, US-Japan relations were very tense for a while. In October 2013, when Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel arrived in Japan for negotiations on the US-Japan defense guidelines, their first stop was to make an offering at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery, (which houses a memorial to unidentified war dead and is considered a neutral war memorial compared to the politicized Yasukuni Shrine). It was a forceful expression of displeasure. Shortly afterward, PM Abe made a visit to Yasukuni. The US embassy issued a statement of “disappointment” over his decision to do so. Abe’s stance creates cracks in the Japan-US relationship.

The US and China have created a dynamic relationship, which I have called “composite hegemony.” The US has no intention of fighting a war with China or building a wall of containment. It aims to maintain a balanced relationship, mixing confrontation and cooperation, while implicitly acknowledging that the two countries will exercise control over Asia and the Pacific. Pivoting its global strategic thrust toward Asia, while facing the pressure of cuts to its military budget, the US seeks to shift some of the burden onto an alliance of Japan, Australia, and South Korea, creating what amounts to a standing multinational force. It aims to exploit Japan to this end. It expects Japan to provide funds, and to make the SDF a force that the US military can more easily utilize.

The third Armitage-Nye report (2012) contains a series of recommendations, such as restarting Japan’s nuclear reactors and increasing the marine-corps capabilities of the Ground Self-Defense Force. It supports removing restrictions on collective self defense, but it does not back revising the constitution. To the US, revising the constitution in what amounts to an open embrace of imperial continuity is a red flag. Except for this, the Abe administration accepted the recommendations across the board, and started to implement them. Abe sees this as the way to maintain the relationship with the US.

The desire to build the country on the third fundamental principle of imperial continuity, and the subordination of Japan to the US are interlinked in a peculiar way. Abe wants to return Japan to its prewar imperial status and return to the ranks of the world powers, with a strong military in place. But, for the foreseeable future, Japan cannot go against the US, in particular it cannot become a nuclear power. So, what can it do? It can curry favor with the US and fulfill the role of subcontractor to the US military. The more Abe follows the Yasukuni course, however, the more the US can raise the price of supporting his government.

The Future Outlook

The fight to change this dynamic is, therefore, a struggle in the realm of fundamental principles: To reconstitute the principle of pacifism forged in the postwar Japanese movement, to build connections to a universal world, and thus to free ourselves from the principles of American domination and imperial continuity. This would amount to transcending the postwar regime from our side, based on the principle of the right to unarmed, peaceful existence.

Our principle is one that can form the basis for policies and the goals of a movement. I think we should set a long-term goal of de-hegemonizing the Pacific. In place of the “we may have spats but we’re the ones in control” composite hegemony of the US and China, we should aim for non-hegemony. But we have to end our integration into the present structure of hegemony, and to take a stance that sides neither with American nor Chinese hegemony, and refuses to recognize their composite hegemony. Keys to this goal are the demilitarization of Okinawa and the signing of a peace treaty between the US and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. This kind of thinking must inform our fight against Abe. We will not side with American or Chinese hegemony. As a true deterrent force, we will bring about peace and reform by forging links among people. In this way, we’ll put an end to the theory of deterrence, which can only lead to an ever-expanding and nuclear arms race.

For this reason, the struggle with the Abe administration over fundamental principles is one that opens new prospects for the future.

Muto Ichiyo is a Japanese writer on political and social affairs. He has been an activist in the anti-war movement since the 1950s. He was active in the anti-Vietnam war Beheiren movement (1965-74), inaugurated the English-language magazine AMPO in 1969, founded the Pacific-Asia Resource Center in 1973, and played a leading role in organizing the People’s Plan 21 program (1989-2002). He founded the People’s Plan Study Group (PPSG) in Tokyo in 1998 and serves on its board of directors. He is the author of many books, the most recent of which isSengo Rejiimu to Kenpō Heiwashugi (The Postwar Regime and Constitutional Pacifism), which was published in 2016.

NOTES

1 In 1949, Emperor Hirohito sent a message through an aide to William Sebald, political advisor to SCAP, in which he stated his views that 1) the US military occupation of the Ryukyu Islands should continue; 2) there should be a long-term lease, with Japan retaining sovereignty; and 3) the procedures should be established by an agreement between the two countries.

2 See George R. Packard,

Edwin O. Reischauer and the American Discovery of Japan (2010).

3 A similar term, “death during public duty” (kōmushi), was used in a set of questions submitted in the Diet to Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro in 2005. Asked whether the honor of Class-A war criminals had been restored, Koizumi ducked the question by responding, “The meanings of ‘honor’ and ‘restore’ are not necessarily clear, which makes it difficult to respond to this question.”

4 Hitotsumatsu Sadayoshi (Reform Party) at an Upper House session on June 9, 1952.

5 In 1905, during the Russo-Japanese War, Prime Minister Katsura Taro and Secretary of War William Taft reached this understanding to recognize each other’s spheres of control. Taft later became president.

Unfortunately, the 9/11 Commission Report came out 14 months later, providing a fourth account, and it contradicted all of the previous accounts and testimony. The Commission’s Report stated that:

Unfortunately, the 9/11 Commission Report came out 14 months later, providing a fourth account, and it contradicted all of the previous accounts and testimony. The Commission’s Report stated that:

eurozone of having a central bank to spend money to revive the European economy. Instead of working to heal the economy from the debt deflation that has occurred since 2008, the European Central Bank (ECB) finances banks and obliges governments to save bondholders from loss instead of writing down bad debts.

eurozone of having a central bank to spend money to revive the European economy. Instead of working to heal the economy from the debt deflation that has occurred since 2008, the European Central Bank (ECB) finances banks and obliges governments to save bondholders from loss instead of writing down bad debts.