African Americans and Mass Struggle during the Early Years of the Great Depression: The Yokinen Trial of 1931

July 18th, 2016 by Abayomi Azikiwe

author Abayomi Azikiwe

Founded in 1919 by at least two factions of the United States socialist movement, what became known as the Communist Party, USA (CP) was faced with formidable obstacles in building a Marxist-Leninist party inside the citadel of world imperialism. In the aftermath of World War I the U.S. was poised to gain hegemony over other capitalist states in Europe resulting from a variety of factors.

With specific reference to the war itself, fighting was largely concentrated in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe along with the territories that constituted sections of the former Ottoman Empire. Consequently, the industrial infrastructure was not damaged by the war and through the need for military equipment the factories were expanding their operations to supply the necessary hardware for the U.S. and its allies.

During the course of World War I racial unrest erupted in several locations throughout the country including incidents involving African American soldiers serving in the military.

In the aftermath of the war a new round of unrest erupted the largest being in Chicago in the summer of 1919.

This expansion in the industrial production of the U.S. in World War I attracted millions of African Americans into the urban areas of the South and North. Competition for housing, jobs and public space pitted African Americans against whites who were born in the U.S. as well as foreign-born European immigrants.

Efforts to organize labor unions and popular organizations inside the country had been hampered by racial divisions which were fostered by the ruling class interests within industry, real estate, commerce and finance. State institutions from the federal government down to the state and local structures reflected the inherent racist character of the economic and social growth of the U.S. which was rooted in the forced removals of the indigenous Native people and the centuries-long enslavement of Africans.

The Political Significance of the Yokinen Trial

At the Second Congress of the Communist International (CI) held in Moscow in 1920 the question of the status of African Americans was discussed and resolutions were passed. Although no African Americans were in attendance, John Reed, who had written an account of the Russian Revolution of 1917, prepared and delivered a report July 25 on the conditions of the Black population in the U.S. and the potential for organizing work among them.

Reed seemed to suggest that the African American people should be approached and organized as workers and not a nationally oppressed group seeking self-determination. Although Reed mentioned the role of A. Philip Randolph of the Socialist Party and the Messenger newspaper that he co-founded, there was no reference to the rapidly emerging Garvey Movement (Universal Negro Improvement Association-African Communities League) or the cultural renaissance taking place in Harlem and other African American communities nationwide.

In his remarks Reed said

“The only correct policy for the American Communists towards the Negroes is to regard them above all as workers. The agricultural workers and the small farmers of the South pose, despite the backwardness of the Negroes, the same tasks as those we have in respect to the white rural proletariat. Communist propaganda can be carried out among the Negroes who are employed as industrial workers in the North. In both parts of the country we must strive to organize Negroes in the same unions as the whites. This is the best and quickest way to root out racial prejudice and awaken class solidarity.”

Reed continues emphasizing

“The Communists must not stand aloof from the Negro movement which demands their social and political equality and at the moment, at a time of the rapid growth of racial consciousness, is spreading rapidly among Negroes. The Communists must use this movement to expose the lie of bourgeois equality and emphasize the necessity of the social revolution which will not only liberate all workers from servitude but is also the only way to free the enslaved Negro people.”

V.I. Lenin, the central figure in the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, in his “Draft Theses on National and Colonial Questions” from the Second Congress of the Communist International of 1920, said after listing a series of oppressed peoples including African Americans that,

“An abstract or formal posing of the problem of equality in general and national equality in particular is in the very nature of bourgeois democracy. Under the guise of the equality of the individual in general, bourgeois democracy proclaims the formal or legal equality of the property-owner and the proletarian, the exploiter and the exploited, thereby grossly deceiving the oppressed classes. On the plea that all men are absolutely equal, the bourgeoisie is transforming the idea of equality, which is itself a reflection of relations in commodity production, into a weapon in its struggle against the abolition of classes. The real meaning of the demand for equality consists in its being a demand for the abolition of classes.”

Lenin continues stressing that

“In conformity with its fundamental task of combating bourgeois democracy and exposing its falseness and hypocrisy, the Communist Party, as the avowed champion of the proletarian struggle to overthrow the bourgeois yoke, must base its policy, in the national question too, not on abstract and formal principles but, first, on a precise appraisal of the specific historical situation and, primarily, of economic conditions; second, on a clear distinction between the interests of the oppressed classes, of working and exploited people, and the general concept of national interests as a whole, which implies the interests of the ruling class; third, on an equally clear distinction between the oppressed, dependent and subject nations and the oppressing, exploiting and sovereign nations, in order to counter the bourgeois-democratic lies that play down this colonial and financial enslavement of the vast majority of the world’s population by an insignificant minority of the richest and advanced capitalist countries, a feature characteristic of the era of finance capital and imperialism.”

However, even though some African Americans and African-Caribbean people were recruited into the Communist Party from the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) and Socialist Party, by 1925 very little had been accomplished on a mass level. In 1925 the CP-initiated American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC) made several attempts to organize conferences bringing together African American workers and intellectuals. Several of these cadres were sent to study in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) at the KUTVA School. Discussions taking place during 1925-1928 in Moscow and the U.S. coincided with factional disputes inside the American Party. By the Sixth Congress of 1928, a full-blown campaign was launched to force the U.S. Communists to develop more effective work among African Americans.

The Garvey Movement and other organizations had made tremendous efforts during the 1920s. Discontent had set in among leading African American cadres claiming that the Party leadership was not taking the plight of Black workers and farmers seriously. By this time the Party was heavily dominated by both Anglo-American whites and foreign-born immigrants from Europe.

Coming out of the Sixth Congress were resolutions that took specific positions on the status and role of African Americans within the struggle for socialism and communism. Placing these developments within an historical context this writer during a 2010 public meeting in Detroit noted:

“Prior to 1928, very few African-Americans had attended the CI congresses. Otto Huiswood, who had been associated with the ABB attended the fourth congress in 1922 along with the Jamaican-born poet Claude McKay. Even though the Sixth Congress had developed the Black Belt thesis and urged greater work among the African-American community, the rightist forces inside the CP advocated the notion of “American exceptionalism,” which implied that the economic conditions of the United States were different than what prevailed in European capitalists states. The rightist forces within the CP refused to fully implement the thesis adopted at the Sixth Congress of the Communist International. By 1929, another major split developed inside the Communist movement. The followers of Jay Lovestone, the majority faction, were expelled along with some members of a minority faction that included James P. Cannon and Max Schatman, who went on to form the Trotskyist movement in the United States.” (Socialism and the Right of Oppressed Nations to Self-Determination)

When the Great Depression took hold in late 1929, the African American community was devastated. Mass unemployment, racist violence, displacements through forced removals from rural areas and housing evictions in urban centers became the norm. The Communist Party by 1930 had established Unemployed Councils which demanded jobs and food for workers facing extreme deprivations. The Councils fought for a moratorium on evictions and blocked bailiffs from throwing families out of rental properties in cities such as New York, Cleveland and Chicago. Several leading Communist organizers among African Americans were killed and wounded in confrontations with the police.

It was during this period that the Party made significant inroads into the African American communities. Hundreds and later thousands began to join rallies, marches, picket lines and rent strikes. When African Americans witnessed both Black and white communists fighting in the streets for their rights to housing, food and civil rights, the Party began to grow exponentially. Leading African American community leaders and labor activists joined the Communist Party in great numbers.

Nonetheless, the party was still dominated by Anglos and foreign-language clubs. Political development was uneven and consequently the overall institutional racist character of U.S. society fostered division along color lines. While thousands of African Americans joined CP-led mass organizations and campaigns along with becoming party members, racist attitudes prevailing in American society remained.

In areas where segregated labor unions either totally barred African Americans from joining or forcing them into Jim Crow locals with limited resources and no real political attention, the CP emphasized the need to reject racism in all of its forms. The bringing together of Black and white workers, both U.S. and foreign-born, brought out reactionary tendencies among the European Americans. Consequently, in order to preserve its gains in the area of mass work as well as growing Party membership among African Americans, the CP opened a campaign against white chauvinism inside the organization.

A Harlem Show Trial

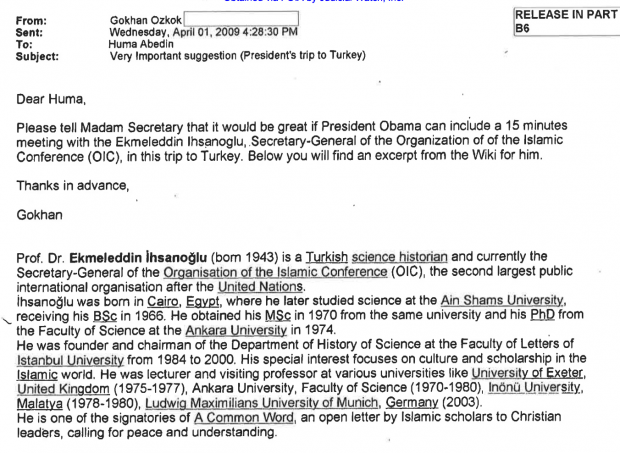

August Yokinen was a Finnish immigrant and a member of the Communist Party in New York. He was charged with white chauvinism and put on trial by the New York District on March 1, 1931. The trial resulted from the apparent racist treatment of a delegation of African Americans who responded to a notice about a public social event held at the Finnish Club in Harlem.

A pamphlet published by the CP in the aftermath of the hearing in 1931 entitled “Race Hatred on Trial”, said

“This club, composed of Finnish workers, regularly gives such entertainments in the very heart of the Negro neighborhood. At this particular dance three Negro workers came to enjoy themselves as did the other workers there. But when these three Negro Workers came they found, that instead of being given the welcome repeatedly promised by the Communist Party and by all revolutionary workers, they were pushed off to one side and given anything but a cordial reception. In addition to this there was a definite group in this hall that showed such an attitude of hostility to these three Negro workers that they wanted to eject them bodily from the hall. I repeat: instead of receiving the welcome they expected, and the opportunity to enjoy themselves, as did the other workers in the hall, these three Negro workers had to leave the hall because of the hostility of certain white workers.” (p.7)

Moreover, according to this same document,

“we find that the Party members, who are also members of this club, instead of going to the defense of the Negro workers, adopted a tolerant attitude to those elements bitterly hostile to the Negroes. While the principles of the Party declare for stubborn opposition to all persecution and discrimination against Negroes, our Party members in this particular club did not fulfil their responsibilities and duties as Party members. They adopted a policy of smoothing over these issues without taking a decisive stand for the defense of the right of the Negro workers to attend this dance together with the white workers. We have in this organization, Party members, apparently, who vote in favor of a resolution which declares equality for Negroes, but when it comes to actually putting equal rights into practice in the Finnish Workers Club, the Party members were not ready to rush to the defense of these Negro workers. On the contrary, by this negative position they aided those who hounded Negroes out of the hall.” (p. 8)

Once this act of racism and white chauvinism came to light among broader segments of the Party an immediate investigation was conducted. Efforts were underway to institute disciplinary actions against those white comrades who failed to come to the defense of the African American workers. Many of the Finnish workers when confronted admitted their mistakes saying they should have maintained the official policy against discrimination as enunciated by the Party and thrown out those who engaged in the racist behavior.

During interviews with the white comrades present, the majority of which took a position of self-criticism, the Party investigative team encountered August Yokinen who attempted to justify the racism shown toward the African American workers. The Communist Party pamphlet reviewing the Yokinen trial said of the accused “He argued that if the Negroes came into the club and into the pool room, they would soon be coming into the bathroom, and that he for one, did not wish to bathe with Negroes. He justified throwing the Negroes out of the dance, because he was afraid if Negro workers were permitted to come to a dance, they would also come to play pool; they would also come to bathe in the excellent bathroom of which the Finnish comrades are justly proud.” (p. 8)

Identifying Yokinen’s view as “A Dangerous Attitude” in a section of the pamphlet, the CP surmised that this sentiment among white comrades was not an isolated one. The Finnish comrade’s outlook represented a formal acceptance of equal rights for African Americans without putting it in to practice. When faced with social situations where racist norms were destined to prevail within U.S. society, the white comrades fell back on to the institutional discrimination which is at the base of the exploitative system of capitalism, serving as a main impediment to building multi-racial class unity within the Communist Party, the trade unions and the mass movement in general.

The report on the Yokinen trial then states “In this he was giving expression to the white-superiority lies that have been developed consciously by the capitalists and the Southern slave-owners. He was taking a position that hindered the mobilization of the Negro masses for struggle together with the white workers under the leadership of the Communist Party. Just so long as any of our Party members take such an anti-Communist stand, we give to the Negro workers the perfect right to mistrust us and our promises. We must bear in mind that others, besides Communists, have also made promises to Negroes. The Socialists, the Republicans, the Democrats, the American Federation of Labor—all of these bodies have and can continue to make promises. But none of these have fulfilled nor will fulfill their promises. The Negroes have learned to expect from them nothing but broken promises and betrayals. They have learned to mistrust all whites.” (p. 9)

Continuing on this same theme, the pamphlets surmises “Unless every member of our Party fulfils in action the Communist promise to the Negro masses they have the same right to distrust us as they have learned to distrust the other Parties. We say, therefore, that when Yokinen opposed the use of the bath room, the pool room, or any other part of the Finnish Club by the Negro workers, he was giving expression to views that undermine the confidence of the Negro masses in the Communist Party and in the revolutionary white working class. And we must guard the revolutionary integrity of our Party by immediately expelling Comrade Yokinen from membership.”

Yokinen was expelled at the conclusion of the trial but offered the potential of renewed membership if he worked within the mass movement for one year defending the rights of African American people. The accused later acknowledged that he had also been infected with anti-Black prejudices and pledged to reform. The CP claimed that Yokinen understood his crimes and would rectify his attitude and behavior.

The Finnish comrade committed himself to working for a year in the emerging League of Struggle for Negro Rights (LSNR), a successor to the ANLC. This new formation largely grew out of the campaign to save the lives and win acquittals in the Scottsboro Boys case in Alabama where African American men were falsely charged for raping two white prostitutes aboard a freight train. This case won national acclaim for the CP and provided openings for the organization of the Sharecroppers’ Union in Alabama.

This case against August Yokinen gained national and international attention through not only the CP publication but through an article published by the Associated Press. The trial was held in Harlem before an audience of 1,500 African American and white workers. The CP pamphlet noted that Yokinen “was not tried before any court of American ruling-class ‘justice’. He was tried by a court of workers. He was brought to trial by the Communist Party for conduct detrimental to the interests of the working class as a whole and for violation of the fundamental program of the Party.”

Nevertheless, due in part to the wide publicity given to the case by the CP, Yokinen was targeted by the U.S. government for deportation. He was accused of violating the terms of his admission in the country by being a member of what was considered a subversive organization. Yokinen was arrested and detained. A campaign arose in his defense by the CP and its mass units even after his expulsion for anti-Black prejudice and racism. Eventually he was deported even though he was married to a U.S. citizen and had fathered a child which was an American.

The Yokinen trial represented the contradictions facing the CP during the so-called Third Period in the aftermath of the Sixth and Seventh Congresses of the Communist International. Demanding that the American Party take decisive action in eradicating white chauvinism and the demand by African American comrades for more direct political work within their communities, the CP was coming into serious conflict with the values and institutions of U.S. capitalism. If they did not attempt to tackle racism within its own ranks, the Party would be doomed to marginalization within the African American communities and consequently be in defiance of the resolutions on self-determination and full equality mandated by the CI.

Harry Haywood, one of the initial recruits into the CP in early the 1920s, became a proponent of the right of self-determination for the African American people. Haywood had studied in the Soviet Union at KUTVA and pressed during the Sixth and Seventh Congress for the resolutions requiring sustained work among the Black workers and farmers in the U.S.

Haywood wrote in an article published in the Communist in September 1933 that

“The first real achievements of our Party in the leadership of the Negro masses date from the beginning of the application of this Leninist line. A historical landmark in the development of our Negro work was the public trial of August Yokinen. In this trial the case of discrimination by a white Party member against Negroes was made the occasion for a political demonstration in which the Party’s program on the Negro question and the struggle against white chauvinism were dramatized with an unprecedented effect before the widest masses throughout the country. Comrade Browder in his report before American students, in estimating the political significance of this trial, declared ‘that it was a public challenge dramatically flung into the face of one of the basic principles of social relationships in America — the American institution of Jim-Crowism… The explusion of Yokinen, expressing our declaration of war against white chauvinism, exerted a tremendous influence to draw the Negro masses closer to us.’ In this trial the Party achieved a great step forward in the education of its membership and the masses around the Party on our program on the Negro question. This was particularly exemplified in Comrade Yokinen himself who, after six months, came back into the Party as one of the staunchest fighters for its program of Negro liberation and who, as a result of his courageous and militant stand on this question, was deported by the Negro-hating imperialist government. The trial of Yokinen served to prepare the Party ideologically for a real interest in the struggle for Negro rights.”

Building on this point related to the struggle against white chauvinism within the CP and the growth in influence by the Party among the African American masses, Haywood says “Only through the vigorous application of our correct Leninist program on the Negro question could the Party carry through and lead such a struggle as the Scottsboro campaign. This campaign gave rise to the sudden movement of mass participation of Negro workers on an unprecedented scale in the general struggles of the working class throughout the country. The great strikes of the Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia coal miners which broke out in 1931, during the first part of the Scottsboro campaign, witnessed greater participation of Negro workers than any other economic action led by revolutionary trade unions. Large masses of Negro workers rallied to the unemployed movement, displaying matchless militancy in the actions of the unemployed. Notable examples of this were the heroic demonstrations against evictions in the Negro neighborhoods of Chicago and Cleveland.

This same article continues saying “While the Negro masses were beginning to participate more in the class struggles in the North, an event of great historical significance occurred in the Black Belt — the organization of the Sharecroppers Union and the heroic resistance of the sharecroppers to the attacks of the landlords and sheriffs at Camp Hill, Alabama. In this struggle the revolutionary ferment of the Negro poor farmers and sharecroppers received its first expression, resulting in the establishment of the first genuine revolutionary organization among the Negro poor farmers — the militant Sharecroppers Union. The agrarian movement of the Negro masses was further continued and developed in the Tallapoosa fight in which the sharecroppers gave armed resistance to the legalized robbery of the landlords and merchants.

This whole series of class and national liberation struggles was further deepened and politicized through the Communist presidential election campaign of 1932. In this campaign the Party was able to further extend its program among the masses, rally large numbers of Negroes behind its political slogans. Thus the application of a Bolshevik program in conditions of sharpening crisis and growing radicalization of the Negroes has resulted in the extension of the political influence of the Party among the broad masses of Negroes, and in the growth of Party membership among them. Of outstanding importance in this period is the establishment of the Party in the South and in the Black Belt.”

Lessons of the Yokinen Trial for Today

Some may question the contemporary significance of the Yokinen trial and the struggle for a Leninist position within the revolutionary movement. Inside the U.S. the “white only” signs have been taken down across the South and the North. However, racism still permeates U.S. society and the emerging anti-racist movement labelled as “Black Lives Matter” has once again raised the questions of the intersections between national oppression, economic exploitation and political repression.

A phenomenon of police killings of African Americans and Latinos has reached epidemic proportions while the state institutions from the federal government to the local entities have failed to discipline, arrest, prosecute, convict and imprison law-enforcement agents and vigilantes who engage in the unwarranted use of lethal and the systematic targeting of oppressed people for liquidation. The first U.S. president of African descent has been in office for nearly eight years amid worsening social conditions for Black people.

Numerous academic and journalistic studies have documented the policies of racial profiling carried out by police agencies around the U.S. In the aftermath of the police killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the Department of Justice (DOJ) conducted a wide-ranging study of the situation involving African Americans and the legal system in St. Louis County.

This author in a review of the Ferguson Report published in 2015 a year after the gunning down of unarmed Michael Brown by white police officer Darren Wilson, notes “In a quote taken directly from the Ferguson Report as it relates to the ostensible Fourth Amendment rights of African Americans which are supposed to protect them from illegal search and seizure, it says that ‘In reviewing Ferguson Police Department records, we found numerous incidents in which— based on the officer’s own description of the detention—an officer detained an individual without articulable reasonable suspicion of criminal activity or arrested a person without probable cause. In none of these cases did the officer explain or justify his conduct. Many of the unlawful stops we found appear to have been driven, in part, by an officer’s desire to check whether the subject had a municipal arrest warrant pending. Several incidents suggest that officers are more concerned with issuing citations and generating charges than with addressing community needs.’” (Modern Ghana, August 4, 2015)

The same article goes on to say “The reasons in part for the aggressive policing operations against African Americans in Ferguson and St. Louis County stems from the desire to reap economic gains through excessive citations which are often reinforced by an already biased court system. Despite these observations by the DOJ investigators no criminal charges for civil rights violations were filed and consequently the situation will remain the same until the realization of a mass revolutionary movement that can effectively challenge the system of racism and national oppression.”

Mass demonstrations have continued throughout the U.S. since 2013 when George Zimmerman of Florida was acquitted in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford. These protests continued after the outrage over the police shooting of Michael Brown spread throughout the country. The Black Lives Matter hashtag started by three African American women Alicia Garza, Patrice Cullors and Opal Tometi, came in response to the acquittal of Zimmerman during the summer of 2013. The hashtag has become a movement and organization mirroring the mounting militancy on the part of African American youth and workers.

By the spring of 2015, Baltimore would erupt in rebellion after the death in police custody of Freddie Grey. More demonstrations and vigils were held nationally providing further evidence of the rising national consciousness among African Americans related to their growing intolerance towards racist violence. In the fall of 2015, these anti-racist demonstrations would erupt on the campuses at the University of Missouri, Princeton, and others. An attack on the tributes paid to ideological racists and imperialists at these institutions emphasized the need for a reinterpretation of U.S. and world history.

The character of the anti-racist demonstrations and other actions varied. Many were led by African Americans while others were more multi-national. These aspects of the movement raise questions as to the character of the required organizational structures which have not yet reached full maturity.

Of course there are limitations to the effectiveness and sustainability of spontaneous demonstrations and even rebellions. During the 1960s and 1970s, mass demonstrations and urban rebellions were widespread and consequently the forms of organization took on a more ideological orientation.

For example, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began through civil disobedience opposing legalized segregation in public accommodations in 1960. By 1961, a staff had been established with a broadening focus on voter registration. By 1964, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) pointed to the necessity of an independent political organization. The founding of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), the first Black Panther Party in Alabama, emphasized the need for both independent politics and self-defense.

By 1966 SNCC had come out in full opposition to the U.S. war of occupation and genocide in Vietnam. The Black Panther Party for Self Defense founded in Oakland, California in October 1966, later ran for political offices in 1968 but also sought to form a revolutionary Black party committed to armed self-defense and fundamental political transformation of U.S. capitalism and imperialism. The Republic of New Africa (RNA) formed in Detroit in March 1968, demanded five states in the South for the establishment of an independent Black nation. Many saw the RNA position as a continuation of the Black Belt Thesis emanating from the Sixth and Seventh Congresses of the CI.

Tensions existed during the 1960s and 1970s among Black and white radicals. Efforts were undertaken in the early 1970s to form multi-racial communist parties which would take into consideration the errors of the various left formations of the period between the 1920s and 1960s. These attempts at the formation of a new Communist movement were not sustainable. Many of the same contradictions involving race, gender and social class would emerge amid the major shifts within the structures of the world capitalist system that began in the early to mid-1970s.

In 2016, if these contradictions in race relations within the left movements themselves, both Black and white, are not resolved, there can be no real advancement in the struggle to transform the racist capitalist system in the U.S. Looking back upon the historical occurrences such as the Yokinen trial of 1931reveals the extent to which these contradictions have not been resolved.

A Black-led movement against racism on an ideological level represents the advancements over the degree of political repression levelled against the struggle during the 1950s through the 1970s by the Counter-intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and other forms of U.S. government subversion of the popular movements for social change. Nonetheless, the role of whites in these demonstrations and movements and their alliances with the African American national liberation struggle requires a systematic study of the triumphs and failures of the past century.

Without question racism must be defeated both within and without of the social justice movements if the organizations are serious about playing a critical role in these reemerging struggles. African American youth are displaying a keen aversion to national chauvinism and attempted marginalization of their concerns. Activists have confronted presidential candidates demanding that they address the plight of the African American people at the hands of law-enforcement and the broader prison industrial complex.

This confrontation will reveal as Bob Marley once said in his song on the Zimbabwe national liberation movement, “who are the real revolutionaries.” Those who reform and adhere to a correct line on the national and class questions of the day will survive and thrive. Others of course will be rendered to the dust bins of history. These developments are inevitable in light of the instability and fracturing within the world imperialist system and its institutions including political parties.

Therefore, the resolution to the issues of the character of the mass movements and revolutionary organizations are pivotal in making the progress necessary to achieve victory over racism, capitalism and imperialism.