GR Editor’s Note.

Included herewith are the main findings and sections of the the IPT report.

To read the entire document click here

EDITORIAL NOTE

This is the Final Report of the Judges who participated in the hearings held in the Nieuwe Kerk, The Hague, Netherlands from 10 to13 November 2015. Before the hearings, the judges received the Indictment and Prosecution Brief, as well as extensive background documentary material in the form of a Research Report of over six hundred pages.

During the four days of hearings, the judges heard the oral submissions of the prosecutors, as well as the testimony and responses to questions of more than 20 witnesses (some of whom testified with their identities protected under pseudonyms and/or behind screens). The judges also received several hundred pages of documents, tendered as evidence. The prosecution presented its case as nine counts, alleging the commission of the following crimes against humanity: (1) Murder, (2) Enslavement, (3) Imprisonment, (4) Torture, (5) Sexual Violence, (6) Persecution, (7) Enforced Disappearance, (8) Hate Propaganda and (9) Complicity of Other States.

Following the hearings, the judges examined the evidence and supporting material further, in their preparation of this Report. Helen Jarvis and John Gittings prepared and edited the Report, assisted by Shadi Sadr, Mireille Fanon-Mendes France and Zak Yacoob. Judge Yacoob provided a legal overview of the text. The Report amplifies and provides reasoned justification for the Judges’ Concluding Statement, delivered during the final session of the hearings on 13 November 2015 (see A3 below). It begins by addressing the overarching question of responsibility for the mass murders and other crimes; it then focuses on the counts presented by the Prosecution and in an amicus curiae Brief submitted to the Tribunal; and concludes with a series of findings and recommendations.

It is regrettable that the State of Indonesia did not accept the invitation to participate in the hearings or make submissions to the Tribunal. The governments of the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia, also did not accept the invitation extended by the Tribunal. The judges welcomed the willingness of individual members of Indonesian National Human Rights Commission, Komnas HAM, and the National Commission on Violence Against Women, Komnas Perempuan, to brief the Tribunal.

It should be noted that some significant though partial steps towards addressing these issues have been taken in Indonesia since the Tribunal was held, as outlined in Appendix D2.

A. THE IPT HEARINGS

A1 Introduction to the International People’s Tribunal by the Organizing Committee

The International People’s Tribunal (IPT) 1965 was established to end the impunity for the crimes against humanity (CAH) committed in Indonesia in and after 1965. These CAH have mostly escaped international attention and are silenced in Indonesia itself. Joshua Oppenheimer’s 2012 film, The Act of Killing, helped to disrupt the international silence. In March 2013 this documentary was launched in The Hague, during the Movies That Matter Festival. After the screening of the film a discussion was held which was attended by 35 exiles, the film director himself, a former member of the Indonesian National Human Rights Commission, and a few activists and researchers. How could the impunity around the CAH committed after 1 October 1965 in Indonesia be ended? The Indonesian government has still not followed up the impressive 2012 report of the Indonesian National Human Rights Commission on the CAH in and after 1965. The failure of the state to try to reach an internal Indonesian solution for these serious crimes made participants decide that international pressure was needed to fight against the impunity the perpetrators continue to enjoy and to break through the silence and stigma surrounding this period in Indonesian history. They felt that the best form for such a campaign would be an International People’s Tribunal, and appointed the human rights lawyer Nursyahbani Katjasungkana to be the general coordinator.

In the first months after the March 2013 meeting a small working team was formed, a Concept Note was drafted, a research coordinator was appointed (Saskia Wieringa), and secretariats and media teams were set up, both in Jakarta and in the Netherlands (led by Lea Pamungkas). The IPT 1965 became a legal entity (foundation) on 18 March 2014. In 2015 prosecutors and prospective judges were approached, the indictment was prepared and the hearings were held.

The Foundation IPT 1965 aims to redress the historic tendency to trivialize, excuse, marginalize and obfuscate these CAH, particularly the rapes and other forms of sexual violence and torture of women prisoners. Furthermore, the suffering of the thousands of Indonesians whose passports were arbitrarily revoked because they refused to support the “New Order” of President Soeharto must be acknowledged as a crime against humanity. The Foundation IPT 1965 has the following objectives:

- To ensure national and international recognition of the genocide and crimes against humanity committed in and after the “events of 1965” by the State of Indonesia, as well as the complicity of certain Western countries in the military campaign against alleged supporters of the 30 September Movement;

- To stimulate sustained national and international attention to the genocide and crimes against humanity committed by the State of Indonesia in and after the events of 1965, and to the continued inaction of the State to bring the perpetrators to justice, by, for example, inviting the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Past Human Rights Violations to Indonesia;

- In the long term: (a) to contribute to the healing process of the victims and their families of the genocide and crimes against humanity in Indonesia in and after 1965; (b) to contribute to the creation of a political climate in Indonesia where human rights are recognized and respected; (c) to prevent the reoccurrence of violence against victims of the genocide and crimes against humanity in and after 1965 and to ensure the fair trial of perpetrators of such violence;

- To provide a public record of the genocide and crimes against humanity committed after 1 October 1965;

- To affirm the uncompromising hope that justice is still possible and that such atrocities will never be repeated, and to contribute to the creation of a political climate in Indonesia where human rights and the rule of law are recognized and respected.

Since 2013, preparatory activities, both in the Netherlands and more importantly in Indonesia, were conducted in preparation for holding the tribunal in The Hague, from 10–13 November 2015. The year 2015 marked 50 years of silence on these crimes.

More than 100 volunteers helped to organize the Tribunal: researchers from all over the world, the media teams in Jakarta and the Netherlands, and many Indonesian students from all over Europe who helped during the hearings. The formal organs of the Foundation IPT 1965 were the Board of the Foundation, the Organizing Committee and the International Steering Committee. Indispensable political and legal advice was provided by our Advisory Board.

A3 Concluding Statement of the Judges of the International People’s Tribunal on the 1965 Crimes Against Humanity in Indonesia read at the Close of Evidence on 13 November 2015

The judges of this Tribunal were appointed by the Foundation of the International People’s Tribunal on the 1965 Crimes Against Humanity in Indonesia to evaluate the upheaval and violence that plagued Indonesia during and after September-October 1965, to determine whether these events amounted to crimes against humanity, to express a conclusion on whether the state of Indonesia and/or any other state should assume responsibility for these crimes and to recommend what may be done in the interests of lasting and just peace and social progress in Indonesia.

The judges regret that neither the government of Indonesia, nor any other state to whom notice was given have made any submissions before this tribunal despite having been invited.

This Statement is made on the 13th day of November 2015, at the end of the hearing of oral testimony of the victims, and of expert witnesses, over four days, having taken into account the broad historical background, much research material, writing and opinion and, in particular:

- the 23 July 2012 Statement by Komnas HAM (National Commission for Human Rights) on the Results of its Investigations into Grave Violations of Human Rights During the Events of 1965-1966;

- the 2007 report, “Gender-Based Crimes Against Humanity: Listening to the Voices of Women Survivors of 1965” by Komnas Perempuan (Indonesian Commission for Violence against Women); and

- the Concluding Observations of the UN Human Rights Committee in 2013 raising concerns about human rights violations in Indonesia in 1965 and after, the reiteration of those concerns in 2015, as well as the concerns expressed in 2012 by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

The broad historical background includes material concerning the government in Indonesia before the events of 1965, accounts of these events and their impact, the years of the Suharto dictatorship until about the turn of the century, the new reformist constitutional era ushered in after the round rejection of the Suharto regime as well as events after that.

The judges have had particular regard to the fact that there is no credible material disputing the occurrence of these grave violations of human rights, the passage in Indonesia of truth and reconciliation legislation in an effort to come to terms with the fact that these events had indeed occurred, the absence of any denial by any government of Indonesia that these events had occurred and the promise made by the President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo, to ensure that these violations will be redressed. All the material demonstrates beyond any doubt that the serious violation of human rights brought to the judges’ attention did occur.

The judges consider that allegations by the prosecution of cruel and unspeakable murders and mass murders of over tens of thousands of people, of unjustifiable imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of people without trial and for unduly long periods in crowded conditions, and the subjection of many of the people in prison to inhumane and ruthless torture and to forced labour that might well have amounted to enslavement, are well founded. It has also been demonstrated that sexual violence, particularly against women, was systematic and routine, especially during the period 1965-1967, that many political opponents were persecuted and exiled, and that many thousands of people who, according to propagandist and hate discourse, were thought not to support the Suharto dictatorship with sufficient fervour, disappeared. All of this was justified and encouraged by propaganda aimed at establishing the false proposition that those opposed to the military regime were by definition grossly immoral and unspeakably depraved.

It has been established that the State of Indonesia during the relevant period through its military and police arms committed and encouraged the commission of these grave human rights violations on a systematic and widespread basis. The judges are also convinced that all this was done for political purposes: to annihilate the PKI (Communist Party of Indonesia) and those alleged to be its members or sympathizers, as well as a much broader number of people, including Sukarno loyalists, trade unionists and teachers. The design was also to prop up a dictatorial, violent regime, which the people of Indonesia have rightly consigned to history. It cannot be doubted that these acts, evaluated separately and cumulatively, constitute crimes against humanity, both in International Law and judged by the values and the legal framework of the new reformist era accepted by the people of Indonesia 17 years ago. This Tribunal has heard the detailed and moving evidence of victims and families as well as the evidence of established experts. It saw this evidence as no more than the mere tip of the iceberg—a few tangible, graphic and painful examples of the devastation of the human beings who appeared before them, as well as the wholesale destruction of the human fabric of a considerable sector of Indonesian society.

The prosecution made the case that other states have aided Suharto’s ruthless regime to achieve these results in the pursuit of the establishment of a particular international order in the context of the Cold War. We will consider this in our final judgment.

The material presented to the judges may amount to proof that other grave crimes have been committed. This issue is also left open for the final judgment.

The judges are sufficiently satisfied of their conclusions to make them public now with confidence. However we need more time to set out in detail the basis upon which we have come to these conclusions. We shall file a final judgment justifying, with reasons, every conclusion and opinion in this statement within the coming months.

The judges consider the state of Indonesia responsible in the commission of such crimes against humanity as the chain of command was organized from top to bottom of the institutional bodies.

Despite the important and positive changes that took place in Indonesia in 1998, emphasizing the importance of human rights in governance, this has not led to a situation in which the successive governments have genuinely addressed past grave and systematic human rights violations.

In addition to the above conclusions, the Tribunal is convinced, on the evidence presented, that material propaganda advanced in 1965, which motivated the dehumanization and thus the killing of thousands of people, included many lies. In particular, the repeated assertion that the generals were castrated has long been disproved by autopsy reports, and these reports have been known to successive governments of Indonesia. It is the duty of the president and government of Indonesia forthwith to acknowledge this falsity, to apologize unreservedly for the harm that these lies have done, and to institute investigations and prosecutions of those perpetrators who are still alive. The Tribunal would have thought that the President would, of course, do all this and be eager to keep his electoral promise. Furthermore, the archives should be opened and the real truth on these crimes against humanity should be established.

In this regard, the Members of this Tribunal note that Komnas HAM commenced investigations in 2008, and that the government of Indonesia has received the commission’s report and recommendations. The government has not implemented these recommendations and in our view should do so as a matter of urgency. These recommendations include appropriate reparation for victims.

We commend the Foundation and the many people who have invested time and energy as well as financial and other resources into this Tribunal. Without all that involvement and determination, such a tribunal would not have been possible. We trust that their efforts will be justified by an appropriate national and international response.

Mireille Fanon-Mendes France

Cees Flinterman

John Gittings

Helen Jarvis

Geoffrey Nice

Shadi Sadr

Zak Yacoob

B. REPORT OF THE JUDGES

B1. Legal framework

The role of the IPT and its panel of judges was clarified in the Public Statement issued in October 2015, before the Hearings, as follows:

As a people’s tribunal, the Tribunal derives its moral authority from the voices of victims, and of national and international civil societies. The Tribunal will have the format of a formal human rights court, but it is not a criminal court. It has the power of prosecution but no power of enforcement. The essential character of the Tribunal will be that of a Tribunal of Inquiry.

Individual members of the Tribunal have extensive knowledge of international and human rights law and of this period of Indonesian history. The judges of the Tribunal will examine the evidence presented by the prosecution, develop an accurate historical and scientific record and, applying principles of international customary law, public international law and Indonesian law to the facts as found, will deliver a reasoned judgment. They will seek to establish, without fear or favour, the truth about these historical events, in the hope that this will contribute to justice, peace and reconciliation.

In their Opening Statement read before the start of evidence the judges said:

There is no doubt that the events of 1965 in Indonesia remain extremely important for Indonesia and for the world.

We believe that the most probable and reliable account of the exact causes of what happened in 1965 and thereafter must be identified, and that this account is necessary if real, lasting and just peace, that includes reconciliation and reparation, is to be achieved in Indonesia.

The panel of judges of the IPT was asked to consider the probity of prosecution charges and submissions that crimes against humanity had been committed in Indonesia in 1965 and beyond, and the state of Indonesia is legally responsible for recognizing, investigating and punishing these crimes under codified international law, customary international law and/or Indonesian domestic law. The judges examined these submissions in the light of their opening statement which, properly interpreted, necessarily implies that serious human rights violations did indeed occur in Indonesia at the relevant time. Therefore, the issues are what were the causes of these violations, and do these occurrences amount to crimes against humanity, in respect of which the State of Indonesia is obliged to act.

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY

Crimes against humanity stand as a necessary ingredient and pillar of customary international law. They were tried for the first time in the Military Tribunals in Nuremberg[1]and Tokyo.[2] The existence of these crimes was later codified in the inspirational Universal Declaration of Human Rights on 10 December 1948 and the Nuremberg Principles by the UN General Assembly in 1950.[3] They were also recognized and accepted as part of Indonesian domestic law, as is mentioned below. We start with customary international law.

As correctly pointed out by the Prosecution, crimes against humanity in customary international law are fundamentally:

- inhumane acts that are crimes in most national criminal law systems

- committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against civilians.[4]

The Prosecution submitted that the inhumane acts are crimes against humanity in international law. It also urged that because under customary international law the prohibition of crimes against humanity is a jus cogens norm, derogation is not permitted under any circumstances.[5] Customary international law therefore obliges these States to prosecute those responsible for the commission of these crimes, or to extradite them to States committed to pursue prosecution.[6]

Two matters must be emphasized. For crimes against humanity in customary international law to be proven there must first be a widespread or systematic attack against civilians. The attack need not be against the entire civilian population but against part of it. Here, as will be shown, the widespread systematic attack targeted the substantial civilian population constituted by the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI), all its affiliate organisations, its leaders, members and supporters and their families (as well as those alleged to have been sympathetic to its aims).[7] Secondly, it is not necessary for the attack to be both wide-ranging and systematic. A wide-ranging attack that is not systematic, and a systematic attack that is not wide ranging, would each qualify separately as attacks which fall within the purview of crimes against humanity in customary international law.

It must also be emphasized that to prove crimes against humanity, the acts which were part of the attack must be deemed crimes in most countries, as demonstrated through state practice. Indeed, the Prosecution submitted that all of the acts to be considered by the IPT qualify as crimes across the world, including in Indonesia, whose domestic law in relation to crimes against humanity does not differ significantly from that of other countries around the world.

In 2000, the Indonesian People’s Representative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR) adopted Law No. 26/2000 (Law 26), establishing a Human Rights Court” in order to resolve gross violations of human rights”, defined by Article 7 as:

gross violations of human rights include both the crime of genocide and crimes against humanity

Article 9 of this law defines crimes against humanity as including any action perpetrated as a part of a broad or systematic direct attack on civilians, in the form of:

- killing (Article 9(a));

- extermination (Article 9(b));

- enslavement (Article 9(c));

- enforced eviction or movement of civilians (Article 9(d));

- arbitrary appropriation of the independence or other physical freedoms in contravention of international law (Article 9(e));

- torture (Article 9(f));

- rape, sexual enslavement, enforced prostitution, enforced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or other similar forms of sexual assault (Article 9(g));

- terrorization[8] of a particular group or association based on political views, race, nationality, ethnic origin, culture, religion, sex or any other basis, regarded universally as contravening international law (Article 9(h));

- enforced disappearance of a person (Article 9(i)); or

10. the crime of apartheid (Article 9(j)).[9]

These follow closely those set out in Article 7 of the Rome Statute of 2000, governing the International Criminal Court.

And Article 43 of Law No. 26/2000 specifically provides for gross violations of human rights that occurred in the past to be heard and ruled on by an ad hoc Human Rights Court. The Article uses the word “shall” and thus renders the formation of the court and adjudication of these offences peremptory.[10]

The definition of crimes against humanity is broadly similar in both customary international law and Indonesian law. The first difference is that the attack must be wide ranging and systematic in customary international law, while it needs to be broad, systematic and direct in Law No. 26/2000. Secondly, the Indonesian law sets out specific acts that must be part of an attack while customary international law requires inhumane acts that are crimes in most countries. These differences are immaterial.

Accordingly this Report sets out to show that:

- there was an attack against civilians: that is the PKI, and those alleged to be its leaders, members, supporters and sympathisers, as well as their families, that was broad or wide ranging, systematic and direct in contravention of customary international law and Indonesian domestic law;

- the ingredients of these attacks relied upon by the Prosecution, namely, mass killings, imprisonment, enslavement, torture, enforced disappearance, sexual violence and persecution through exile, which are crimes in most national jurisdictions and covered by Law No. 26/2000, were indeed committed.

The inquiry by Komnas HAM, the government’s own Indonesian National Human Rights Commission into the 1965–66 events , undertaken pursuant to Law No. 26/2000, and in the light of the definition of crimes against humanity as set out in its Article 9, concludes its report with the following statement:

After having carefully examined and analysed all the findings discovered in the field, the statements of the victims, witnesses, reports, relevant documents and other information, the Ad Hoc Team to Investigate the Committal of Grave Crimes Against Humanity During the 1965/1966 events has reached the following conclusions:

- There is adequate initial evidence to believe that the following crimes against humanity, which are serious crimes against basic human rights, occurred:

- Killings (Article 7, letter b jo[11] Article 9 letter a of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts).

- Exterminations (Article 7, letter b, jo Article 9 letter b, of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Enslavement (Article 7, letter b jo Article 9 letter c of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Enforced evictions or the banishment of populations (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 letter d of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Arbitrary deprivation of freedom or other physical freedoms (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 letter e of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Torture (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Rape or similar forms of sexual violence (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 letter g of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

- Persecution (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 letter h of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

10. Enforced disappearances (Article 7 letter b jo Article 9 letter I, of Law 26, 2000 on Human Rights Courts.

The aforementioned actions were part of an attack aimed directly against the civilian population, namely, a series of actions against the civilian population as a consequence of the policy of the authorities in power. As these actions were widespread and systematic, these actions can be classified as crimes against humanity.[12]

The Prosecution Brief also argued strongly that the International Law Commission’s Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (ARSIWA) also imposes obligations and responsibility on the State of Indonesia for violations of crimes against humanity; it referred specifically to Article 40(2), which considers a serious breach to be constituted by gross and systematic failure by the responsible State to fulfil its obligations.

The Judges in their Concluding Statement emphasized that they had taken into particular account:

- the 23 July 2012 Statement by Komnas HAM (National Commission for Human Rights) on the Results of its Investigations into Grave Violations of Human Rights During the Events of 1965–1966;[13]

- the 2007 report, “Gender-Based Crimes Against Humanity: Listening to the Voices of Women Survivors of 1965” by Komnas Perempuan (Indonesian Commission for Violence against Women);[14] and

- the Concluding Observations of the UN Human Rights Committee in 2013 raising concerns about human rights violations in Indonesia in 1965 and after, the reiteration of those concerns in 2015, as well as the concerns expressed in 2012 by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.[15]

[1] 1945–1946.

[2] May 1946 to November 1958.

[3] Indonesia became a member of the United Nations on 12 June 1950. On 20 January 1965, during Konfrontasi (Indonesia’s military and political confrontation campaign against the formation of Malaysia), in response to the election of Malaysia as a non-permanent member of the Security Council, Indonesia informed the United Nations by letter that it wished to withdraw. A second letter was sent on 19 September 1966 notifying the Secretary-General of its decision “to resume full cooperation with the United Nations and to resume participation in its activities”. However, the Charter makes no provision for withdrawal of membership from the United Nations, and it appears that Indonesia did not thereby derogate from any of its treaty obligations. (See Blum, Yehuda Zvi (1993), Eroding the United Nations Charter. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-2069-7, cited in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Member_states_of_the_United_Nations#cite_note-81.)

[4] Article 9 of Law No. 26, Year 2000, Establishing the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court; Article 7 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998); Article 5 of the Statute of the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (1993); Article 3 of the Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (1994).

[5] Cherif Bassiouni, Crimes Against Humanity: Historical Evolution and Contemporary Application (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 263.

[6] Article 9. Obligation to extradite or prosecute of International Law Commission, Draft Code of Crimes against the Peace and Security of Mankind with commentaries, 1996. New York: United Nations, 2005.

[7] Although, as discussed in B2, instructions were issued and attacks launched from as early as 1 October 1965, the PKI and its affiliates were officially banned in 1966 by the People’s Representative Assembly (MPRS). Ketetapan (Tap) No XXV/MPRS/1966 MPRS Resolution No. XXV/1966 adopted on July 5, 1966 by the Provisional People’s Consultative Assembly (MPRS), which outlawed the teachings of Marxism-Leninism.

Article 2 of this Resolution reads as follows: “All activities undertaken in Indonesia to spread or promote the beliefs or teachings of Communism/Marxism-Leninism in all its forms and manifestations, using whatever means including the media for the spread and promotion of these beliefs or teachings, shall be prohibited.”

Indonesia is a signatory of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the provisions of which are binding upon Indonesia.

[8] In the Indonesian original penganiayaan is used. It is normally translated as “persecution,”as used in English texts on crimes against humanity.

[9] Republic of Indonesia, “Law No. 26 Year 2000 – Establishing the Ad Hoc Human Rights Court,”translation published by Asian Human Rights Commission, accessed through the website of the International Red Committee of the Red Cross https://www.icrc.org/.

Note: The numbering of Article 9 in this translation has been garbled, and is corrected here.

[10] Article 43 of Law 26 provides:

“1. Gross violations of human rights occurring prior to the coming into force of this Act shall be heard and ruled on by an ad hoc Human Rights Court.

- An ad hoc human rights court as referred to in clause (1) shall be formed on the recommendation of the House of Representatives of the Republic of Indonesia for particular incidents upon the issue of a presidential decree.

- An ad hoc human rights court as referred to in clause (1) is within the context of a Court of General Jurisdiction.”

[11] The translation of sentence 1a, h and i published by Tapol has been corrected here to conform to the Indonesian original text of Komnas HAM, Ringkasan Eksekutif: Laporan penylidikan pelanggaran HAM berat (Jakarta: KomnasHAM RI, 2012) p. 25. It uses the term “jo” throughout (abbreviation of Latin word juncto, meaning “in conjunction with”).

[12] Komnas HAM Report. This 470-page Executive Summary of the results of their investigation into ten cases, of which 40 pages relate to the 1965-66 events, was signed on 23 July 2012 by Nur Kholis, the Chair of Komnas HAM’s Ad Hoc Investigation Team into the 1965-66 Events, on the Results of its Investigations into Grave Violations of Human Rights During the Events of 1965-1966. http://www.tapol.org/sites/default/files/sites/default/files/pdfs/Komnas%20HAM%201965%20TAPOL%20translation.pdf (see Appendix D1.f for its conclusions).

The full text of the Komnas HAM Report has never been officially published, although copies of what appears to be the authentic text are in circulation.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Komnas Perempuan, Komnas Perempuan, Kejahatan Terhadap Kemanusiaan Berbasis Jender: Mendengarkan Suara Perempuan Korban Peristiwa 1965.( Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan, 2007). Published in English as Gender-Based Crimes Against Humanity: Listening to the Voices of Women Survivors of 1965, (Jakarta : Komnas Perempuan, 2007). Available at http://home.patwalsh.net/wp-content/uploads/Listening-to-the-Voices-of-Women-Survivors-of-1965.pdf. See Appendix D1.e for the recommendations in this Report.

[15] July 2013: UN HRC: “Concluding observations on the initial report of Indonesia” (see Appendix D1.g); UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, “Concluding Observations: Indonesia”, CEDAW/C/IDN/CO/6-7, 27 July 2012.

B2. Responsibility and Chain of Command

The Prosecution made a strong case that all these crimes:

were committed under the full responsibility of the State. General Suharto assumed immediately on 2 October 1965 de facto control of the capital and the armed forces. A new Operations Command for the Restoration of Security and Order (“Kopkamtib”) was established on 10 October to implement the liquidation of the PKI and alleged sympathisers. On 1 November General Suharto was appointed as the Chief Commander of the Kopkamtib. Consequently, this Command operated under the direct orders of General Suharto…

General Suharto and his associates immediately blamed the PKI as the masterminds of the G30S [Abbreviation of Gerakan September Tiga Puluh (30 September Movement)—added by Report editors]. A military propaganda campaign distributed pictures of the dead generals with claims that Communists, particularly Communist women, had tortured and butchered them before death. As a result, violence and demonstrations by the army and various youth groups, equipped and/or supported by the military and the government, targeting suspected Communists soon broke out in Aceh, Central and East Java, before spreading all over Indonesia. Civilians were killed, raped, tortured, enslaved or subjected to other crimes against humanity in their own homes or in public places.

On 21 December 1965, General Suharto issued an order (Kep-1/KOPKAM/12/1965) for military leaders around Indonesia to compile lists of members of PKI and PKI-affiliated organisations in their respective areas. Civilians whose names were included in these lists became the targets for gross human rights violations including murder, torture and other crimes, as has been reported by the Indonesian National Commission for Human Rights (Komnas HAM).

On the basis of the above, the following questions need to be asked relating to the issue of responsibility:

- Did the state of Indonesia acknowledge at the time, or has it since acknowledged, its responsibility for the mass killings and other crimes against humanity which occurred in 1965 and afterwards?

- What was the chain of command between the central state and the lower levels of authority alleged to have carried out the killings, and what was the relationship between state authorities and local militia or other groups which are alleged also to have carried out the killings?

- Acknowledgement

Since the restoration of democracy in Indonesia in 1998, two Presidents have made statements on the need for the government to address the mass killings of 1965.

In 2000, the then President Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur, the first elected president after Suharto resigned in 1998) discussed at some length in a TV interview his concern for “the victims of G30S/PKI” and suggested that his government would welcome opening up the case to determine the truth of what happened. He also acknowledged that members of the Islamist mass organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) — of which he was formerly the chairman — had participated in the killings and said that he had already apologized for their actions.[1]

The interview as reported in Kompas included the following remarks:

Much earlier, when I was still General Chair of the Board of the NU, I already apologized to the victims of the G30S/PKI.

The government welcomes it if society wants to open up the case of G30S/PKI and the other cases of human rights violations.

Much earlier I already apologized. Not only now — ask the friends in the NGOs — I already apologized for all killings that happened to people who were called communists….

It is not at all sure that people who were accused of being communists were all wrong so that they were sentenced to death. Prove it to the courts, not just like what happened. Gus Dur went on to say that if the G30/PKI issue were opened up again, it would be good to have a debate among the people of Indonesia. “For many people think that the PKI members were wrong. There are also those who think they committed no mistakes. Well because of that we had better decide via a legal procedure which is right.”

The current President Joko Widodo, in a mission statement issued in May 2014 shortly before he was elected, pledged that:

We are committed to bring about a just solution to past human rights violations that still impose a socio-political burden on the Indonesian nation, such as the May disturbances, the 1st and 2nd Trisakti-Semanggi events, forced disappearances, the Talang Sari-Lampung and Tanjung Priok incidents and the 1965 tragedy.[2]

The official investigation body established by Komnas HAM concluded in its Statement of 23 July 2012 that, on the basis of its investigations:

- There is adequate initial evidence to believe that the following crimes against humanity, which are serious crimes against basic human rights occurred… a. Killings … b. Exterminations … c. Enslavement … d. Enforced evictions or the banishment of populations … e. Arbitrary deprivation of freedom or other physical freedoms …

- Torture … g. Rape or similar forms of sexual violence … h. Persecution …

- Enforced disappearances ….

- Based on the wide range of crimes which occurred and the picture of victims who have been identified and the mountain of evidence that is available, the names of those who implemented these crimes and were responsible for the events of 1965/1966 are the following, added to which there may be more.

- Individuals/military commanders who can be called to account:

a.1 The commander who decided on the policy:

- PANGKOPKAMTIB – the Commander of KOPKAMTIB from 1965 until 1969.

1970. PANGKOPKAMTIB – the Commander of KOPKAMTIB from 19 September 1969 at the least until the end of 1978.

a.2 The commanders who had effective control (duty of control) over their troops.

The PANGANDAs and/or PANGDAMs [regional and local Commanders] during the period from 1965 until 1969 and the period from 1969 until the end of 1978.

- Individuals/commanders/members of the units who can be held responsible for the actions of their troops in the field.

Contemporary documentary evidence of the killings is almost completely lacking and appears to have been suppressed by the military authorities. It has been noted that “under the New Order, little was heard of the killings” and that “official and semi-official accounts, such as the National History of Indonesia and the so-called ‘White Book’ on the 1965 coup, famously ignored the killings, and there was a widespread perception that they could not be discussed publicly.”[3]

In a rare exception, a document does exist—dated 8 November 1973—in which the Jaksa Agung (Attorney General) issued an instruction to local prosecutor offices in Indonesia to set aside (not to prosecute) the cases of killings against members of the PKI and/or of PKI-affiliated organizations, as they had “arisen from popular anger and spontaneity of the masses.” It was feared that pursuing these cases would “give rise to psychological effects among G30S/PKI remnants emboldening their struggle, could be used by international organisations affiliated with or under the influence of the international communist movement and would cause apathy in society towards helping the Government and state instruments in the future.” It also stipulated that they must consult with the Laksusda(Special Territorial Administrator) in order to provide evidence that would prove that those killed were indeed members of the PKI and/or PKI-affiliated organizations. Further, they were requested by the Attorney General to avoid exposing to third parties this “setting-aside process” (specifically the media).[4]

An admission of state responsibility may also be inferred from statements by government ministers and senior politicians seeking to justify what occurred. In a recent example, the former coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs, Djoko Suyanto, issued a public statement on 1 October 2012 rejecting the Komnas HAM Report, saying that the killings were justified to save the country from communism and that there should be no official apology. Suyanto stated that “this country would not be what it is today if it didn’t happen. Of course there were victims [during the purge], and we are investigating them.”[5] And, most recently, such a view was expressed by Coordinating Minister for Politics, Law, and Security, Luhut Pandjaitan, in his Opening Remarks to the National Symposium on the 1965 Tragedy, held in Jakarta, 18–19 April 2016, “We will not apologise. We are not that stupid. We know what we did, and it was the right thing to do for the nation.”[6]

It should be noted that this National Symposium was the first time that the Government of Indonesia has facilitated the public discussion of a wide range of views regarding the 1965 events, and that its outcomes are not yet clear, as is discussed below in Appendix D2, Attempts at Redress and Reconciliation.

- Chain of command

There is abundant evidence, set out in a number of academic studies of this period, that a vertical system of military control and repression was established on the direct authority of General Suharto and conveyed through a series of Orders from Jakarta to the lower levels. Although orders and operations began in some areas as early as 1 October 1965, the main vehicle for this operation was Kopkamtib, set up on 10 October 1965 with General Suharto as its Commander (Pangkopkamtib). Instructions to lower levels in the army were issued as numbered Orders from Kopkamtib or from other military institutions, such as the Ministry of Defence or Army Strategic Reserve Command (Komando Cadangan Strategis Angkatan Darat, Kostrad), which Suharto already commanded. These were replicated or amplified by army commanders at lower levels (see below in this section for material from Aceh).

Starting with an order issued by Suharto on 1 October, the central theme throughout was the need to “annihilate” (menumpas) the G30S Movement (which was often described as “counter-revolutionary”).[7] But the G30S Movement was simply a euphemism for the PKI and every person directly or indirectly connected with it. This order was quickly replicated by Lieutenant General A.J. Mokoginta, the commander for Sumatra of the Supreme Operations Command (Komando Operasi Tertinggi, Koti) who called on all members of the Armed Forces to “resolutely and completely annihilate this counter-revolution and all acts of treason to the roots.”[8]

While initially the object of such instructions might appear to be limited to the small number of alleged leaders of the 30 September Movement, it was always so and soon became clear that the target was much broader, and applied to anyone who might be identified as belonging to, supporting or sympathizing with the PKI, directly or indirectly. Many other people also suffered who did not regard themselves as having any connection or even sympathy with the PKI. As time went on, the target broadened further to clear the ground for a thorough restructuring of society in which both the bureaucracy and the army were cleansed of left-leaning people in general, including many supporters of President Sukarno and progressive members of the Nationalist Party of Indonesia, PNI, who in many cases also suffered persecution.

Furthermore, some of the orders explicitly authorized army commanders to take action outside the law. Those orders given in the first three months of the operation have been summarized, on the basis of research into the original texts, by Mathias Hammer as follows:

Suharto tasked the commanders at the district level with establishing investigation teams (TEPERDA, Team Pemeriksa Daerah, or regional investigation teams) which were to interrogate prisoners and collect information about them (Army Strategic Reserve Command (KOSTRAD), Decree Kep-069/10/1965, in: Kopkamtib 1970). He also wanted these teams to assist the commanders in “taking measures for a solution

of the prisoners” (“mengambil tindakan penjelesaian pada tawanan/tahanan”), a bureaucratic euphemism for mass murder that smacks of the “final solution” with which the Nazis tried to veil the Holocaust. These solutions were to be “either according to the law or according to the special discretion” of the commanders (Army Strategic Reserve Command (KOSTRAD), Decree Kep-069/10/1965, in: Kopkamtib 1970). The last word on life and death was thereby entrusted to the district or KODIM commanders (Komando Distrik Militer, District Military Command). Between late October and late December 1965, the organisational structure involving a variety of “investigation” and “prosecution” teams, with central bodies in Jakarta and various subcomponents of their own, became more and more elaborate – Kammen and Zakaria (2012 p. 447) offer more details on this point. “Screening teams”, as these bodies were often called, eventually existed all over Indonesia, spreading along with the persecution of the PKI. In assessing individual cases, Suharto’s orders mandated the teams to also gather testimonials from witnesses (Army Strategic Reserve Command, decree Kep-70/11/1965, in: Kopkamtib 1970). Not only direct involvement in the 30th September Movement, but also attitudes towards that movement became criteria for persecution.

Finally, it was clarified that attitudes and activism from the time before October 1965 –the so-called “prologue” to the 30th September Movement – would be criteria for persecution as well (Ministry of Defence decree Kep-1/Kopkam/12/1965, 21 December 1965, in: Kopkamtib 1970).

Suharto thereby widened the legal and practical scope of persecution from the relatively small cabal of army officers involved in plotting the kidnapping of the seven army officers who were killed in Jakarta to the socio-political behaviour of millions of ordinary citizens throughout the archipelago. Obtaining information from civilian informants about such behaviour became a valid part of the procedure which local commanders and their teams were to follow in identifying individual execution targets.”[9]

From November 1965 onwards, orders were also issued for a system of classification to be applied to PKI suspects, and as time went on this system was refined further. On 18 October 1968 the Commander of Kopkamtib issued a Decision detailing that,

Those involved in the treasonable G30S/PKI movement are classified as follows:

- Those who were clearly involved directly….

- Persons clearly involved indirectly….

- Persons of whom indications exist or who may reasonably be assumed to have been directly or indirectly involved.[10]

There is no official account of how these operations were conducted throughout Indonesia. The Indonesian press, which quickly fell under military control, almost uniformly refrained from reporting any information regarding the killings. One researcher, John Roosa, notes that “according to the press coverage, the ‘destruction’ of the PKI ‘down to the roots’ was an almost bloodless affair.” In a rare exception, three Jakarta newspapers ran stories in February-March 1969 about Army-organized killings in the Purwodadi District of Central Java.[11] We may speculate on the existence of records kept by the Indonesian army, but if they exist they are not yet in the public domain.

However, the US embassy in Jakarta was able at the time to obtain information from army sources, and information on the army’s role in carrying out or organizing killings is contained in numerous reports from the embassy and the CIA to Washington. Telegrams in November 1965 give a detailed account of the way in which the Army Para-Commando Regiment (RPKAD) in Central Java mobilized civilian militias to assist it in arresting suspected PKI members and in disposing of them. Two researchers who have used this material, Douglas Kammen and David Jenkins, summarize the procedure as follows:

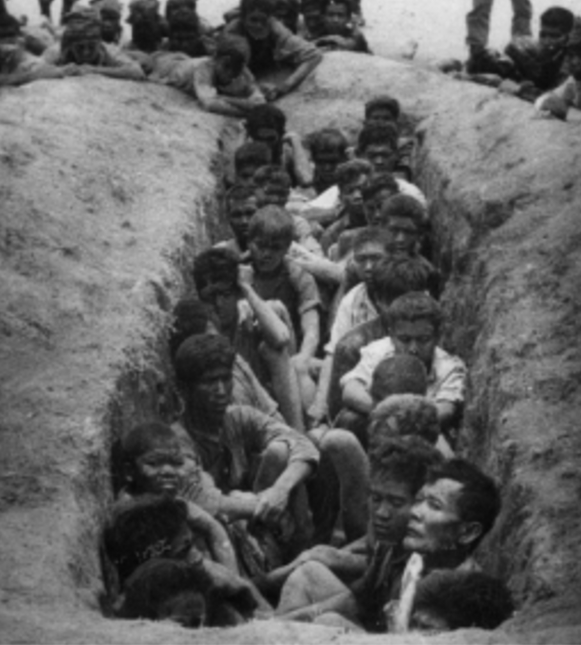

The most common procedure was for civilian paramilitaries operating under the direction of a small RPKAD post to arrest suspected communists and then take them to designated detention centres. The detainees were interrogated, however briefly, to separate PKI cadres from ordinary Party members, sympathisers, and relatives. Cadres were taken to isolated locations and killed. But this left large numbers of detainees, whom the military was neither interested in nor capable of feeding and housing. The solution was for military personnel to ‘move’ detainees at night and en route hand them down to designated civilian death squads.[12]

A rare insight into the killings in the one region—Aceh in northern Sumatra—is provided by internal documents from the Aceh Military Command, obtained by another academic researcher, Jess Melvin, who has made her work available to the Tribunal. On the basis of these documents, Melvin describes the killing process as “occurring in four distinct phases in the province: these phases include an initiation phase; a phase of public–‐spectral–‐ killings; a phase of systematic mass killings; and a, final, consolidation phase.” Other documents obtained by Melvin in Aceh show in detail how “the military and civilian government supported the formation of death squads, which the military and civilian government pledged to provide with ‘assistance’.” [13]

On the few occasions when the mass killings were mentioned openly in official sources, these were ascribed to popular anger, while no reference was made to military involvement. One example is the speech by President Suharto on 11 March 1971, on the fifth anniversary of the “Supersemar” order supposedly signed by then President Soekarno, which led to Suharto’s assumption of full powers. [14] In this speech Suharto claimed that mass killings had occurred in the countryside in 1965–66 as a result of pre-existing political tensions.[15] An official narrative sponsored by the Army and published in English for foreign consumption in 1968 acknowledged that mass killings had occurred, but described them as supposedly spontaneous acts by ordinary people wishing to punish the PKI for its coup attempt. It claimed that the people, “seeing justice neglected… decided to act as judges themselves, which resulted in the mass killings in Central and East Java and other parts of Indonesia.”[16]

However, the latest research in various regions is bringing a new perspective, revealing considerably more information on the degree to which even those killings that were carried out by non-military actors were planned, armed and facilitated (in short, engineered) by the Army. Of particular significance is the research by Indonesian scholar Yosef Djakababa, published in 2013, and more recently by John Roosa, who in April 2016 concluded that it negates the widely accepted:

dualistic thesis … that the violence was committed by a combination of army personnel and civilian militias, with the role of each varying by region.

The dualistic thesis does not grasp the striking uniformity in these descriptions in such widely dispersed locales. For all the diversity in the anti-communist violence, one finds a remarkable consistency across the provinces in the practice of disappearing people who had already been taken captive. One finds army personnel organizing the civilians, administrating the detention camps, and arranging the trucks to transport the detainees to the execution sites. [17]

Legal considerations

The state is responsible in international law for illegal acts which are expressly committed by it or on its behalf without its repudiation and punishment. Since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, it has also been a well-established principle that states and their superior or command-level military and civilian officers are responsible for the actions of their agents or servants, or by individuals under their effective command and control, or authority and control, even if these have not been explicitly authorized.

States also have a general responsibility under international law to take all possible measures to ensure that crimes against humanity are not committed by any persons within their jurisdiction, whether acting for the state or not, and to bring such acts to an end and take action against those responsible.

Furthermore, under the doctrine of superior responsibility, superior officers (both military and civilian) have responsibility for preventing or punishing illegal acts by those under their effective command and control, or authority and control. For example, Article 29 of the law of 2004 setting up the Cambodian Extraordinary Chambers to prosecute crimes committed in the period of Democratic Kampuchea provides that:

[the fact that illegal acts] were committed by a subordinate does not relieve the superior of personal criminal responsibility if the superior had effective command and control or authority and control over the subordinate, and the superior knew or had reason to know that the subordinate was about to commit such acts or had done so and the superior failed to take the necessary and reasonable measures to prevent such acts or to punish the perpetrators.

The acts of mass killing and associated crimes in 1965 and subsequently, and the failure to prevent their occurrence or to take action against their perpetrators, occurred under the full responsibility of the State of Indonesia. Senior members of the Indonesian government have acknowledged that these crimes were committed, but few have expressed a desire to investigate them or apologize for them. Although contemporary reporting of them was mostly suppressed by the military Suharto regime, there were occasional admissions that they occurred. Subsequent investigation by Indonesian and other researchers has exposed the orders and directives which link that regime to the crimes committed in various regions of Indonesia, showing a coherent chain of command from Jakarta to the lower levels. To the extent that some crimes may have been committed independently of the authorities, by so-called “spontaneous” local action, this did not absolve the government at the time from the obligation to prevent their occurrence and to punish those responsible.

This Report will not repeatedly indicate in the text, but it needs to be borne in mind throughout, that all the crimes against humanity committed during this time, and described in detail below, were against a discrete and large part of Indonesian society: the communists in Indonesia and everyone connected with them however remotely.

Notes

[1] “Gus Dur: Sejak Dulu Sudah Minta Maaf”, Kompas, 15 March 2000, accessed at http://indoprogress.com/2014/04/masihkah-meragukan-maaf-gus-dur/. His remarks elicited a hostile reaction from many Muslim political and religious leaders, see further Goenawan Mohamad, “Remembering the Left”, in Grayson J Lloyd & Shannon L Smith, eds., Indonesia Today: Challenges of History (Rowan & Littlefield, 2001), pp. 131-32.

[2] Extract from Joko Widowo’s main electoral platform as appeared in English as “The road towards an Indonesia that is sovereign, independent and with its own distinctive identity: Vision, Mission and Action Program,” Kalla, Jakarta, May 2014, accessed at http://abbah.yolasite.com/resources/VISI%20MISI%20JOKOWI%20JK.pdf. The other violations mentioned include the May 1998 riots, the shootings at Trisakti University in Jakarta in the same month, the February 1989 army killings at Talang Sari, Lampung, and in Tanjung Priok in September 1984.

[3] Robert Cribb, “Unresolved problems of the Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966, Asian Survey, XLII:4, July-August 2002, p. 559.

[4] Jaksa Agung Republik Indonesia, Nomor instr-007/J.A/11/1973 “Tentang penylesaian perkara pembunuhan oknum2 G.30.S/PKI” [Concerning resolution of cases of killing G.30.S/PKI operatives]. (A copy of the original document was supplied to the Tribunal).

[5] Accessed at http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/10/02/govt-denies-1965-rights-abuses-happened.html.

[6] Jess Melvin, “Symposium on Indonesia’s 1965 genocide opens Pandora’s box”, New Mandala, 9 May 2016. Accessed at http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2016/05/09/symposium-on-indonesias-1965-genocide-opens-pandoras-box/.

[7] Alex Dinuth, Dokumen Terpilih sekitar G.30S/PKI. [Selected Documents on G.30S/PKI] (Jakarta: Intermasa, 1997), p.59.

[8] Mokoginta, Letdjen A.J., “Koleksi Pidato2 Kebidjaksanaan Panglima Daerah Sumatra” (Medan: Koanda Sumatera, 1966) p. 152.

[9] Hammer, Mathias “The Organisation of the Killings and the Interaction between State and Society in Central Java, 1965”, in: Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 32, 3, 37–62 (2013). Used by permission.

[10] “The Decision of the Commander of the Kopkamtib no.kep-028/kopkam/10/68 (issued and operative from 18th October 1968) as amended by the Decision of the Commander of the Kopkamtib no.kep-010/kop /3/1969 (issued on 3rd March 1969 to operate retroactively for the period since 18th October 1968).” Amnesty International, Indonesia: An Amnesty International report (London: Amnesty International Publications, 1977), Appendix 1. (See Appendix D1.c for the full text of this Decision.) It should be noted that a further Decision by the President was made on 28 June 1975 concerning government employees who were still being detained as Category C prisoners. KepPres No. 28/1975.

[11] Sources cited by John Roosa in Contours, p. 45. n. 41. Two of these reports are translated in Robert Cribb ed., The Indonesian killings of 1965-6; Studies from Java and Bali. (Clayton, Victoria: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, 1990 (Monash papers on Southeast Asia no. 21).

[12] Jenkins and Kammen in Contours, p. 94, citing Airgram A-353, US Embassy Jakarta to State Department, 30 Nov. 1965.

[13] Jess Melvin, “Mechanics of Mass Murder: Military Coordination of the Indonesian Genocide”, paper presented at ‘“1965” Today: Living with the Indonesian massacres,’ Amsterdam, 2 October 2015 (Publication forthcoming).

[14] It is to be noted that the original of this document has never been released publicly, and there is considerable controversy regarding its contents and the circumstances under which President Sukarno signed, or did not sign, it.

[15] Suharto, “11 Maret Untuk Mengatasi Situasi Konflik Ketika Itu”, Kompas, 11 March 1971. Cited in Roosa, Contours, p. 45, n. 44.

[16] Notsusanto and Saleh, The Coup Attempts, p. 42.

[17] Yosef Djakababa, “The Initial Purging Policies after the 1965 Incident at Lubang Buaya,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 3/2013; John Roosa, “The State of Knowledge about an Open Secret: Indonesia’s Mass Disappearances of 1965–66.” The Journal of Asian Studies, published online 25 April 2016.

B3. Mass Killing, Imprisonment, Enslavement, Torture and Enforced disappearance

No one disputes that a very large number of Indonesians lost their lives in the mass killings of 1965 and after: nearly all estimates give a number of at least six figures. It is also a matter of record that tens of thousands were placed into prisons and camps over the following years without proper legal process: a significant number were subjected to forced labour and torture, were executed or died in captivity. There are also numerous reports, although harder to quantify, of people who were picked up or arrested (seldom through any formal process) and who then disappeared.

Given the accepted magnitude of killings and imprisonment, it is not strictly necessary for the purpose of reaching a conclusion in terms of international or human rights law to establish the precise, or even the approximate, figure. However, given the high degree of interest which this issue of numbers has always attracted, it was necessary to undertake an examination of several of the principal sources in order to give a summary of the estimates given over the past 50 years.[1]

a) Mass Killing

Statistical sources for the mass killings fall into three categories:

- a significant number of contemporary reports by foreign diplomats and journalists (no statistical information was published in the Indonesian press), who suggest an overall figure for killings up to that point. For example, the British ambassador in Jakarta, Andrew Gilchrist, informed the Foreign Office on 23 February 1966 that a previous estimate of 400,000 was considered by his colleague the Swedish ambassador, who had conducted some research in the field, to be an underestimate.[2] A few days later, the US journalist Joseph Craft reported in the Boston Globe that “Indonesia, the fifth most populous country in the world, has been the scene of a continuing massacre on the grand scale–some 300,000 persons killed since November but here the slaughter evokes no concern.”[3]

- a very small number of estimates from Indonesian government sources, for which we only have second-hand information. Two are often quoted: (a) an early estimate in November 1965 by a fact-finding commission appointed by President Sukarno which produced a figure of 78,000 to that date. (The figure was apparently derided as too low even by members of the commission); and (b) a later estimate by Kopkamtib in mid-1966, said to have been based upon a sample survey and circulated to foreign journalists, which gave a round figure of one million, of whom 800,000 were in Central and East Java, and 100,000 each in Bali and Sumatra.[4] The latter has been described by the Australian scholar Robert Cribb as being “a genuine attempt to obtain reliable figures, but its conclusions cannot be accepted with any certainty.”[5] Also often quoted is the statement by the Kostrad commander Sarwo Edhie who while on his death-bed allegedly told Permadi, a well-known diviner, that in this period some three million people were killed, and most of them on his orders.[6] There appears to be no corroboration of this statement.

- Accounts by participants, eyewitnesses and observers, typically confined to one area or one incident. The Komnas HAM Report of 2012, which confined its enquiry into the events of 1965-66 to only six separate areas, provides many examples such as this:

Killings in Flores Timor Kampung [region of Maumere]

The witnesses were people who had seen the killings in several places in the district of Maumere. People were brought there in trucks with their hands tied, taken down from the trucks and led to the edge of a trench. There were altogether 84 persons, of whom 36 had been taken from prison while others had been arrested in the mountains.[7]

Reports of this kind which come from many parts of the country indicate the widespread nature of the extermination campaign (the Komnas HAM enquiry, which had limited resources, noted that one of its main problems was “the huge geographical spread of the 1965-1966 Events”). Such reports also often illustrate in graphic detail the horrendous nature of the killings. However, they remain too scattered for any meaningful statistical aggregation.

The first systematic attempt to collate and analyse the varied and often not very satisfactory statistics from the above sources was made by Robert Cribb in his introductory chapter to the previously mentioned volume, published in 1990. This publication made a dramatic impact when it appeared and is still relied on today for its overview of the range of estimates, as well as its preliminary analysis of the difficulties in reaching any firm conclusions, and the reasons for both under-reporting as well as over-reporting. Cribb presented the available evidence in a table which showed estimates ranging from 78,000 to one million. However, he stated at the outset that:

We know surprisingly little about the massacres which followed the 1965 coup attempt. The broad outline of events is clear enough. The killings began a few weeks after the coup, swept through Central and East Java and later Bali, with smaller scale outbreaks in parts of other islands. In most regions, responsibility for the killings was shared between army units and civilian vigilante gangs. In some cases the army took direct part in the killings; often, however, they simply supplied weapons, rudimentary training and strong encouragement to the civilian gangs who carried out the bulk of the killings. The massacres were over for the most part by March 1966, but occasional flare-ups continued in various parts of the country until 1969. Detailed information on who was killed, where, when, why and by whom, however, is so patchy that most conclusions have to be strongly qualified as provisional….

The nature of the killing in 1965-66 – commonly dispersed, nocturnal and by small groups – was such that no-one could possibly have had first or even second hand involvement in more than a tiny proportion of the total number of deaths. Any estimate of the total number who perished must therefore be a composite of numerous reports, themselves probably also composites of reports.[8]

A 2013 review by Annie Pohlman gives continuing appreciation to Cribb’s 1990 overview, while providing several more recent estimates. Pohlman notes that the killings remain “a murky part of Indonesian history.” While a number of critical studies since Cribb’s work had “improved our knowledge about the who’s, the where’s and the why’s” there were “many factors, trends, actors and motivations which remain unclear….”[9]

In summary, then, Cribb’s assessment in 2001 still stands: “A scholarly consensus has settled on a figure of 400–500,000, but the correct figure could be half or twice as much,”[10] and “We are unlikely now to find empirical evidence to resolve this question.”[11]

Legal Considerations

Killing is named as a criminal act in almost all legal and moral codes, up to the specified crimes of murder and extermination as crimes against humanity in the Rome Statute of 2000, and in Articles 138–140 of the Indonesian Criminal Code (KUHP) and as Article 9 (a) and (b) of Law No. 26/2000. As legal scholars have observed:

The primacy of the right to life in the international order for the protection of human rights is self-evident; if it is not respected, those other rights already deemed to fall within the scope of contemporary customary international law-such as the right to equality and the prohibition against slavery and systematic racial discrimination, as exemplified by apartheid – would become meaningless.[12]

The deliberate taking of human life represents, of course, the quintessential crime against humanity. Lists of crimes against humanity, beginning with the IMT Charter and up through the ICTY and ICTR Statutes, the ILC’s 1966 Draft Code and the ICC Statute, begin with this crime.[13]

The acts documented above, in which it is widely understood that at least half a million people were killed in the aftermath of the G30S events, clearly constitute violations of crimes against humanity under international customary law of murder, appropriately the first count to be brought before the Tribunal by the Prosecution.

Considering the scale and scope of these killings, they may also be qualified as the crime against humanity of extermination, whose character is described as follows:

‘Extermination’ consists first and foremost of an act or combination of acts which contributes to the killing of a large number of individuals. Criminal responsibility for extermination therefore only attaches to those individuals responsible for a large number of deaths, even if their part therein was remote or indirect. By contrast responsibility for one or for a limited number of such killings is insufficient in principle to constitute an act of extermination. Acts of extermination must, therefore, be collective in nature rather than directed towards singled-out individuals…. any act or combination of acts could amount to extermination if contributed, whether immediately or eventually, directly or indirectly, to the unlawful physical elimination of a large number of individuals.[14]

b) Imprisonment

In the first months of the army-led campaign, many thousands accused of being PKI members or belonging to associated organisations were arrested and put into prison or into makeshift detention centres.

As early as 25 October 1965, General Abdul Haris Nasution (Army Chief of Staff, and the only targeted general who managed to escape the killings on the night of 30 September) described the process, although he refrained from naming the PKI:

It is clear who the enemies are within. It is clear because in every institution, including the SAB (Staf Angkatan Bersendjata or The Armed Forces Staff), the cleaning and regulating process are currently going on. The elements of these political adventurers or their supporters are being swept out, and people are now sweeping them out and hunting them down everywhere.[15]

Then on 12 November General A. H. Nasution issued Instruction INS-1015/1965 that spelled out three categories of individuals within the armed forces who were to be “secured” (those clearly involved, clearly involved in an indirect way, and those who can be presumed to be involved directly due to their involvement with the PKI). This was the precursor of the later ABC classification and the first purge instruction to name the PKI.[16] (See Appendix D1.c for a more detailed later version of this classification.)

Three days later, General Suharto, in his capacity as Commander of Kopkamtib, issued Directive, no. 22/KOTI/1965 widening the application of the three categories to be purged to the civilian bureaucracy.[17]

On 12 March 1966, as his first official act after gaining a handover of power to act in the name of President Sukarno, General Suharto signed Presidential Decree 1/3/1966 declaring the PKI to be a banned organisation throughout the territory of Indonesia, and declaring all its structures dissolved, from the centre to the regions, and including all its affiliated and related organisations.[18]

Another decree issued in May 1966 designated the mass organisations which were now proscribed. As well as the PKI structure down to the village committee level, the list comprised 22 mass organisations and 25 educational institutions. The all-Indonesia trade union federation, SOBSI (Sentral Organisasi Buruh Seluruh Indonesia), with a reported membership of over 3 million was included, with a sub-list naming 62 separate trade unions. Baperki, an organisation for Indonesian citizens of Chinese ethic origin, was also proscribed (together with three related institutions).[19]

Prisoners were said to be subject to a screening process to determine whether they belonged to one of other of the categories and/or the proscribed groups.[20]

As to how the authorities determined the appropriate classification for detainees, the Tribunal was presented with a written report and oral testimony by Dr. Saskia Wieringa regarding the procedures adopted for psychological testing of prisoners to determine classification, which “came to be a substitute for law.” Further, she documented collaboration in this process between Indonesian and Dutch psychologists.[21]

An overall figure for those detained (known as tapol, abbreviation for tahanan politik, political prisoners) is often given as one million. Official statistics began to be issued in the mid-1970s of the numbers in detention and of those who had been released (most of the latter were designated as ET (ex-tapol), and they and their families continued (and in some respects continue today) to suffer from loss of civil rights, denial of the right to free movement or to work in certain fields etc.). By 1975-6, a total variously stated as 500,000, 600,000, or 750,000 was officially stated to have been arrested and detained in the years immediately following 1965. In one such statement, Foreign Minister Adam Malik said in April 1975 that:

Immediately after the abortive coup in 1965, we began in 1966 to seize people for interrogation who had been connected with the coup. The number at that time was about 600,000. On the basis of our prevailing laws, our religious conscience and our humanitarian conscience, we immediately began to discover whether people were guilty or not. In that process, from a total of 600,000 there are now only about 20,000 left, and they fall into various categories. These people will be brought to trial. Those who already have been found not guilty have been released. As others are found not guilty, they too will be released.[22]

These figures were queried by Amnesty International and other critics, and Indonesian officials themselves admitted that the real total might be higher. In September 1971 the former Indonesian Prosecutor General, General Sugih Arto, told foreign journalists in Jakarta that “it is impossible to say exactly how many political prisoners there are. It is a floating rate, like the Japanese yen vis-a-vis the dollar.” He explained further that local commanders were empowered to arrest and interrogate suspects, and that “these people can be held for an unlimited period of time. It is not always compulsory to report such security arrests to the central command in Jakarta.[23] Very few of these detainees, who might be held for 10 years or longer, were ever subjected to any form of trial process. According to Amnesty International, “by early 1977, of the hundreds of thousands arrested in connection with the 1965 events, the government claimed to have tried about 800 prisoners in all, that is, an annual average of less than 100 cases.” Access to these trials was denied to foreign jurists.[24]

According the official account by the Armed Forces themselves, published in 1995, 1,887 prisoners were classified in Group A, of whom 1,009 were eventually tried by one of several types of court, and 878 were transferred into group B (none of whom was destined to be tried). Most of these former group A prisoners were sent to the forced labour camps of Buru Island.[25]

Legal Considerations

Considering the universal proscription of arbitrary and unlawful imprisonment under international customary law, the acts brought before the Tribunal, as documented above, support the Prosecution’s charge of violation of Article 9 (e) of Law No. 26/2000, as argued:

- …imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law is considered a crime against humanity….

…the State of Indonesia, acting individually or in concert with other organisations, arbitrarily arrested and imprisoned large numbers of members, followers

and sympathisers of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and PKI-affiliated organisations without trial and the vast majority detained without warrant of arrest and in violation of international law. In this regard, the absence of a valid arrest warrant rendered the initial arrest unlawful, additionally detainees were never informed of the reasons for their detention, nor were they formally charged, or informed of any procedural rights.

- On the contrary, the approximately 1 million prisoners were detained on a categorisation administered by psychologists and based on an assessment of their apparent level of communist loyalty. The prisoners’ categorisation was usually an indication of whether they would survive and thus the psychologists in essence were performing the role of de facto judges.[26]

c) Enslavement

Considerable evidence was tendered by the Prosecution, charging that many of those who were detained were forced to work under conditions that amounted to enslavement, one of the oldest established crimes under international law and constituting a crime against humanity.

The Prosecution Indictment gave the following examples: Monconglowe (called Moncong Loe by Komnas HAM), South Sulawesi; Buru Island, Maluku; Balikpapan, East Kalimantan; Nusa Kambangan and Plantungan, Central Java; and in several prisons in West Java.

The Komnas HAM Report in relation to prisoners confined to the island of Buru reached the following conclusion:

The island of Buru, in the Moluccas: Some 11,500 political prisoners were brought there. Slave labour also took place in the concentration camp in the island of Buru. Witnesses informed the Komnas team that they had to work without pay in a reservoir, a dam, the office of the camp commander, a cement factory, a housing complex, and they had to till the rice fields of the local population and of the officers without pay. They also testified that 90% of the wives of the prisoners were ordered to sexually service both military and civilian men. Komnas HAM concludes that slave labour took place on the island of Buru. This includes sexual slavery.[27]

Amnesty International reported in 1973 that in the women’s prisoners’ camp in Plantungan, Central Java,

…the women must work from morning until night in the fields to produce their own food stuffs. They are only provided with rice and vegetables and must rely on their relatives for other food, such as sugar, tea and coffee as well as soap and clothes. Relatives are not permitted to visit prisoners at Plantungan and although food parcels can be sent, communications are difficult and costs are high.[28]

Written evidence was submitted to the Tribunal describing this system as follows:

In many places of detention, political detainees were not only put to work within the confines of their camp. Here tapols were transported from their prisons to work for a pittance or no payment at all in infrastructure and building projects or plantations. This transportation took place under surveillance, either on daily basis or longer periods depending on the distance of the project area to the prison and on the type of project. In all cases there is speak of forced labour in captivity, whereby slavery conditions prevailed. Reports of such situations exist from Central Sulawesi (Palu, Donggala, Poso), North Sumatra (Asahan, Langkat, Deli Serdang), East- and Central Java as well as East and West Kalimantan.[29]

Two witnesses gave oral testimony during the Tribunal hearings, namely factual witness Mr. Basuki Bowo (pseudonym) and expert witness Dr. Asvi Warman Adam. Mr Basuki Bowo testified to his nine years’ imprisonment on Buru Island, during which time he was subject to intensive and extreme forced labour (without any remuneration) in the construction of infrastructure in the previously undeveloped jungle, and subsequently of cultivation of food crops, much of the produce of which was sold for the benefit of the guards and commanders.