(Please read the previous parts prior to this article)

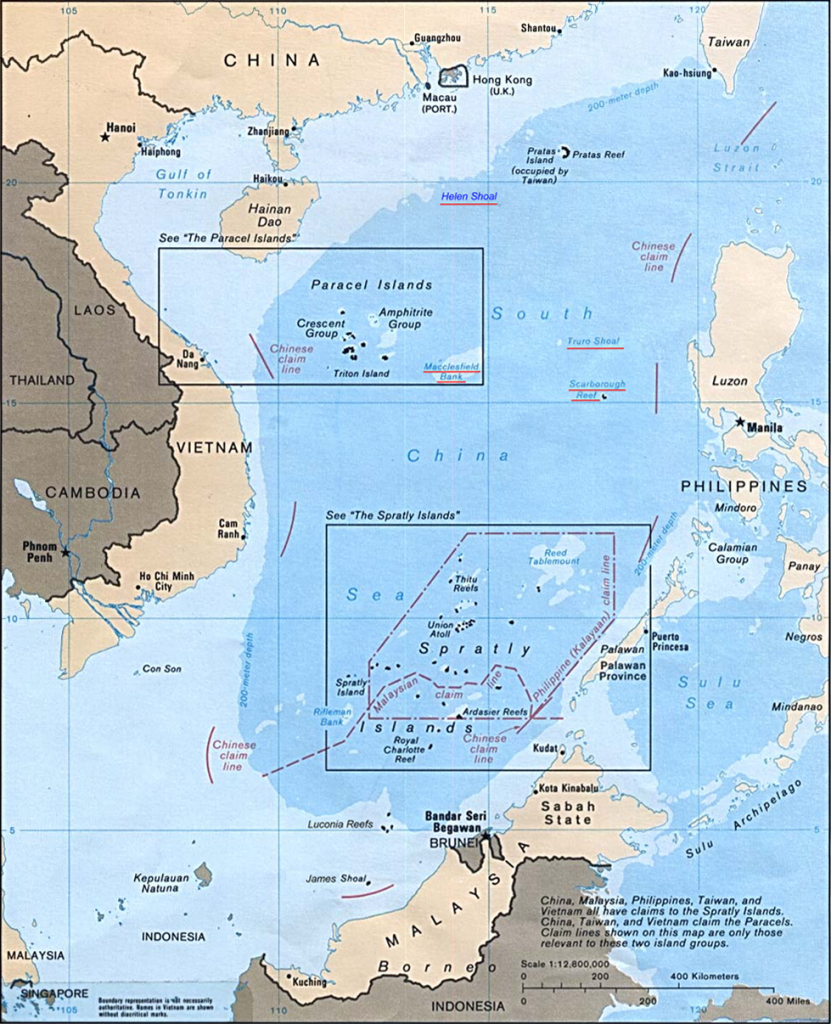

Insular ASEAN has a strategic role in presiding over maritime access points to the region and beyond, but it’s mainland ASEAN and its political stability that most directly affect China’s core strategy at the moment. It’s highly unlikely that circumstances will rapidly change to the point where China is completely cut off from the South China Sea and the international waterways around it, but it looks ever case that its access will come under the watchful gaze of the Chinese Containment Coalition (CCC) and that the potential for military-strategic blackmail might one day arise. In order to counteract this crippling scenario, Beijing is progressively taking steps to circumvent its full dependence on the waterways and balance this with a more substantialized on-the-ground infrastructure presence, the ASEAN Silk Road and the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

Both of these ambitious projects were comprehensively discussed at the beginning of the research’s ASEAN focus, and it’s predicted that the US will go to extraordinary lengths to disrupt their full implementation. To remind the reader, the Law of Hybrid War is “to disrupt multipolar transnational connective projects through externally provoked identity conflicts (ethnic, religious, regional, political, etc.) within a targeted transit state”, so it naturally follows that Color Revolution and Unconventional War schemes with be hatched against these countries in order to stop China’s strategic ‘escape’ from maritime containment. There are essentially three situational theaters in mainland ASEAN – Indochina, Thailand, and Myanmar – and the research will progress to examining each of these Hybrid War battlefields in that sequential order.

Indochina Backgrounder

The first area to be studied is Indochina, taken to mean the former French colonies of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. As with the other countries that have been geopolitically dissected thus far, it’s imperative that the reader first acquaint themselves with a relevant historical background prior to commencing the Hybrid War investigations. This will imbue the individual with an understanding that allows them to recognize the utility of certain socio-political variables to the scenarios that are subsequently described.

The Indosphere Meets The Sinosphere:

Indochina lies precisely at the geographic convergence point of Indian and Chinese civilizations, and as such, there’s actually a clear delineation point between them inside this subregion. For the most part, Cambodia and Laos fell under Indian cultural influence and their historical kingdoms were “Indianized” to a broad extent, while Vietnam was under Chinese control for over a millennium from 111 BC to 938 AD. The effect of these separate civilizational forces on such a small geographic area was to accentuate identity differences between these two adjacent parts, the legacy of which continues into the present day and is likely to once more become a driving factor in forthcoming events.

Indochina lies precisely at the geographic convergence point of Indian and Chinese civilizations, and as such, there’s actually a clear delineation point between them inside this subregion. For the most part, Cambodia and Laos fell under Indian cultural influence and their historical kingdoms were “Indianized” to a broad extent, while Vietnam was under Chinese control for over a millennium from 111 BC to 938 AD. The effect of these separate civilizational forces on such a small geographic area was to accentuate identity differences between these two adjacent parts, the legacy of which continues into the present day and is likely to once more become a driving factor in forthcoming events.

By itself, the civilizational separateness that “Indianized” Cambodia and Laos feel towards “Sinified” Vietnam wouldn’t coalesce into a sufficient agent for political action on its own, but the historical trend of Vietnamese expansionism at their expense (some of it subjectively so, other parts only perceived as such) reveals itself to be the catalytic cause. Neither country outright rejects Vietnamese influence, nor are they in an economic position to do so even if they wanted to, but the point is that their history of relations with Vietnam undoubtedly plays a role in why these two states want to diversify away from their former mono-dependence on their neighbor (experienced from 1975-1991) and achieve a balance through complementary relations with civilizationally similar Thailand and economically expanding China.

Caught In The Middle:

Being situated between their larger Thai and Vietnamese neighbors, Cambodia and Laos have historically been under pressure from both of these powers and eventually turned into the object of their conquests. The golden age that each of these modern-day states had prior to their submission came during the era of Cambodia’s Khmer Empire and Laos’ Lan Xang kingdom, stretching between 802-1431 and 1354-1707, respectively. After that, each of these once-glorious entities fell under the control of the Kingdom of Ayyuthaya, nowadays referred to as Thailand. Vietnam didn’t become a significant player in the rest of Indochina until after it completed its centuries-long “Nam tiến”, which was the state’s piecemeal incorporation of the southern parts of the country that only ended in the early 1800s.

Siamese Ebb, Vietnamese Flow:

After Vietnam’s contemporaneous consolidation, it fought two wars with Thailand from 1831-1834 and1841-1845 over Cambodia, but the object of their mutual rivalry eventually requested French “protection” in 1867 and threw off both of its neighboring rivals. It became France’s second colony after “Cochinchina”, the southern part of Vietnam, fell to an invasion and was occupied by the Empire a couple years earlier in 1862. Just a little over three decades later, Laos was added to the list of French conquests in 1893 following the Franco-Siamese War of the same year.

With their Indochinese imperial realm acquiring a great deal of strategic depth and coming to encompass almost the entirety of its eventual territory, the French were in a comfortable position to accelerate the economic exploitation of their colonies, with a concentrated focus on what is today Vietnam. It should be noted, however, that modern-day Vietnam was actually divided into three separate colonies by the French – Tonkin, Amman, and Cochinchina – but taken as an aggregate, Vietnam’s colonial economic output was much more valuable to Paris than Cambodia and Laos’. The period of French Indochina was also the first time that these two states were grouped together under the same umbrella as Vietnam, heralding a state of affairs that would go on to continue with various ups and downs until the end of the Cold War.

World War II And Greater Thailand:

Indochina was largely spared from the ravages of Japan’s traditional wartime occupational practices, although by no means was it totally immune. Still, Tokyo had less of a militant presence in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos than it did in Indonesia and the Philippines, for example, and the entire territory of French Indochina remained under their control until the end of the war. What’s notable about this period though isn’t necessarily the influence that Japan exercised over the former French colonies, but the role that Thailand played in reasserting its territorial claims eastward.

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (popularly known as Phibun) became Prime Minister of Thailand in 1938 and led his country on an irredentism campaign to re-annex parts of Cambodia and Laos after the Franco-Thai War from 1940-1941. He also expanded Thailand’s territoryinto northeastern Myanmar’s present-day Shan State and the northern territories of Malaysia, all of which he claimed used to be part of his kingdom prior to the advent of colonialism. Thailand was able to get away with all of this because it was an ally of fascist Japan at the time, and it wasn’t until 1946 that it rescinded all of its irredentist claims as part of a deal in exchange for joining the UN.

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (popularly known as Phibun) became Prime Minister of Thailand in 1938 and led his country on an irredentism campaign to re-annex parts of Cambodia and Laos after the Franco-Thai War from 1940-1941. He also expanded Thailand’s territoryinto northeastern Myanmar’s present-day Shan State and the northern territories of Malaysia, all of which he claimed used to be part of his kingdom prior to the advent of colonialism. Thailand was able to get away with all of this because it was an ally of fascist Japan at the time, and it wasn’t until 1946 that it rescinded all of its irredentist claims as part of a deal in exchange for joining the UN.

Despite representing an outburst of militant Thai nationalism, this brief period was not overly influential in determining the future attitudes of Cambodians and Laotians towards Bangkok, partly because of the civilizational similarities between all three peoples and also due to the fact that only portions of their respective territory (and not all of it) were annexed. Another factor that played a role was that the annexations were only in effect for five years. After World War II, Vietnam’s influence replaced Thailand’s and remained the paramount social factor impacting on these two countries’ affairs.

The First And Second Indochinese Wars:

The struggle against the French and Americans was a heroic one of epic proportions, and readers should look more into it on their own time if they have an interest in these exploits. For the sake of time and scope, the summarized relevance of this period of time to the research at hand is that it represented the on-the-ground expansion of (North) Vietnamese influence into Cambodia and Laos, with the Vietnamese communists training and supporting their Khmer Rouge and Pathet Laos counterparts during the entire conflict. In fact, if it wasn’t for crucial support from Hanoi, neither Phnom Penh nor Vientiane would have cast off their respective pro-Western governments, with all three countries liberating themselves from imperialism in full during the dramatic year of 1975. Alas, the conclusion of these two anti-imperialist wars weren’t a harbinger for the end of the region’s conflicts in general, and a few forthcoming ones would soon break out that would derail Indochina’s dynamics.

Post-Imperialist Conflicts:

Vietnam vs. Cambodia

The first war that broke out after the end of the anti-imperialist struggle was the one between Vietnam and Cambodia in 1978-1979. Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge government had turned on its former Vietnamese benefactors and began aggressively demanding territorial revisions in southern Vietnam’s Mekong Delta region. The supposed reasoning for this is that the lands of the late Cochinchina had historically been inhabited by ethnic Khmer (the majority demographic in Cambodia) and were only forcibly incorporated into Vietnam after the end of Nam tiến. There were also intra-communist Cold War considerations at play too, with Vietnam and its Laotian ally being aligned with the Soviet Union, while Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge authorities were very close to China (partly in order to balance against Vietnam’s 19th-century historic interests over the country). Although Vietnam righteously and quite accurately claimed that it was liberating Cambodia from the genocidal rule of the Khmer Rouge (which had killed up to a quarter of the country’s population in only four years’ time), it’s clear in retrospect that it was also pursuing clear geopolitical interests at the same time, installing a pro-Vietnamese government in Pol Pot’s wake and bringing the country fully under its influence as a result.

Vietnam vs. China

As an immediate response to the overthrow of China’s regional ally, Beijing invaded the northern part of Vietnam in mid-February 1979, intent on punishing its erstwhile partner and sending the strongest possible message that it totally denounced its actions. Neither side gained anything tangible from this brief but bloody campaign, but it’s worthwhile to remind the reader that this conflict occurred after China had already de-facto sided with the US in the Cold War. Seen from this vantage point of contextual insight, it’s evident that Beijing was enforcing Washington’s will by proxy against its hated Vietnamese enemy, whether it wittingly did so or was unknowingly guided into this scenario.

The exacerbation of intra-communist Cold War tension between China and the USSR also played to the US’ grand strategic advantage, and it was shortly after this conflict ended that the US took the decision to provocatively arm the Afghan Mujahedin on 3 July, 1979 in order to provoke a Soviet intervention. In the grand global scheme of things, China had put the Soviets’ position in Southeast Asia on the relative defensive while also ensuring that it would redirect a sizeable number of its forces to defending the joint border. Concurrently, the US started using radical Islam to stir up trouble in the USSR’s southern front with Afghanistan, and it was only one year later in 1980 that the anti-Soviet,CIA-influenced Solidarity movement would be created in order to tempt an Afghan-like intervention in Eastern Europe.

Taken together, the situationally coordinated anti-Soviet advances that had popped up in this short two-year period in Southeast Asia, the Chinese frontier, Afghanistan, and Poland are evidence that the US was serious in influencing a concerted effort aimed at destabilizing the USSR along as many of its strategic fronts as possible. Seeing as how this also coincided with the “Reagan Doctrine” of ‘rolling back’ the Soviet influence in Africa (e.g. Ethiopia, Angola, and Mozambique) and Latin America (Nicaragua), it can be said that the Sino-Vietnamese War was actually the opening salvo in this forthcoming worldwide campaign.

Vietnamese-Thai Border Skirmishes

After militarily withdrawing from Indochina, the US resorted to using Thailand as itsLead From Behind to promote their strategic vision in the region. Both Washington and Bangkok supported the Khmer Rouge and other insurgents against the Cambodian-based Vietnamese forces and newly installed pro-Hanoi government, effectively giving the Cambodian Civil War the foreign support that it needed to continue indefinitely. As part of its anti-insurgent campaign, the Vietnamese military would launch raids along the joint Thai-Cambodian border, even engaging in select cross-border attacks against fleeing militants.

After militarily withdrawing from Indochina, the US resorted to using Thailand as itsLead From Behind to promote their strategic vision in the region. Both Washington and Bangkok supported the Khmer Rouge and other insurgents against the Cambodian-based Vietnamese forces and newly installed pro-Hanoi government, effectively giving the Cambodian Civil War the foreign support that it needed to continue indefinitely. As part of its anti-insurgent campaign, the Vietnamese military would launch raids along the joint Thai-Cambodian border, even engaging in select cross-border attacks against fleeing militants.

The tensions that boiled up with Vietnam all along Thailand’s southeastern border with Cambodia would later directly express themselves in the Thai-Laotian Border War of 1987-1988, during which Bangkok and Vientiane (the latter supported by the Vietnamese forces that were based in the country) had a brief military conflict over their disputed frontier. Despite not resulting in any status quo changes, the incident was symbolic in the sense that it showed that the entire Thai-Indochinese border region was ‘fair game’ for proxy conflicts, especially considering that the Vietnamese military was based in both Cambodia and Laos at the time. The escalation of border tension with Laos was significant in that it occurred at the period of time when hostilities between Thailand and Vietnam were subsiding over Cambodia, thus showing that the US-backed authorities in Bangkok were insistent on advancing their anti-Vietnamese goals in some form or another no matter what third-party state was used to achieve these ends.

Interestingly enough, the US’ proxy policy of Southeast Asian destabilization via its Lead From Behind partner of Thailand carries with it a strong foreshadowing of what would later happen in the Mideast after the formal US military withdrawal in 2011. Just as the US withdrew from South Vietnam in 1973 but later used Thailand as its base of covert operations to destabilize its regional foe, so too did it do something similar by withdrawing from Iraq in 2011 but using Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar to continue promoting its anti-Syrian and anti-Iranian agendas, albeit in a more accelerated manner than it had done vis-à-vis Vietnam. Therefore, clear links of strategic continuity can be witnessed between the US’ Cold War policy in Indochina after 1973 and its current one in the Mideast after 2011, with both being characterized by an asymmetrical proxy offensive that follows a conventional retreat.

Indochina After The Cold War:

The changing global dynamics brought about by the end of the Cold War had a monumental impact on Indochina. First off, the most noticeable change was that Vietnam formally withdrew its military from Cambodia and Laos, thereby lessening the direct expression of its influence over these two neighboring states. In turn, Vietnam was able to concentrate its focus on internal economic affairs as opposed to external military-political ones, and the Western community lifted its anti-Vietnamese sanctions that were initially implemented in response to the 1978 Vietnamese-Cambodian War and subsequent military presence there. Due to the institutional relief that Vietnam experienced from this and the positive reaction that the pro-Western members of the region had to these dual developments, Hanoi was able to rapidly incorporate itself into the global economy, joining ASEAN in 1995 and establishing very close trade ties with the US, Japan, and South Korea afterwards.

Cambodia and Laos would go on to join ASEAN as well, albeit in 1999 and 1995, respectively. Instead of moving closer to the US and its East Asian allies, however, they would actually opt to intensify full-spectrum relations with China and Thailand. While both maintain cordial and somewhat close ties with Vietnam (Laos much more so than Cambodia), it can subjectively be assessed that they are no longer as strongly under its influence as they once were. Laos is integrating itself into the ASEAN Silk Road and becoming the literal link between China and Thailand, whereas Cambodia has blossomed into a bastion of Chinese economic and diplomatic influence. The current governments of these two Indochinese states are firmly in the sphere of the multipolar world, with their position exponentially increased by Thailand’s new pro-multipolar leadership.

That isn’t to say that Vietnam isn’t somewhat multipolar as well, seeing as how it beneficially cooperates with Russia in the economic and military realms, but overall the country has come under the strong influence of the unipolar anti-Chinese states of the US and Japan, with the TPP being the ultimate epitome. Going forward, it’s expected that Vietnam will balance its South China Sea maritime strategy with ambitious asymmetrical mainland inroads into its former ‘backyards’ of Cambodia and Laos, partly out of its own desire to economically entrap these two states into its subregional TPP influence zone, but also due to the US’ strategic guidance in using Hanoi’s historical proxy leadership over them to complicate China’s One Belt One Road plans.

The Vendetta Against Vietnam

Vietnam is currently one of the US’ closest strategic partners in the South China Sea, with bilateral relations on the strong upswing out of the shared economic interests and the joint vision of containing China. While ties are unprecedentedly positive between these two states, Vietnam might one day begin reasserting its strategic sovereignty against the US vis-à-vis a possible improvement of relations with China.

That doesn’t look all that probable in the given moment, but it certainly can’t be disregarded, especially since China is Vietnam’s largest trading partner and likely will remain so for at least the rest of the decade (despite the TPP and barring any anti-Chinese sanctions over the Spratly Islands dispute). In the event that Vietnam more pragmatically engages China and perhaps even chooses to fully participate in the One Belt One Road project, then it would draw the strong consternation of the US, whether this is publicly expressed or relegated to backdoor talks.

Just as the US stands to manipulate domestic Hybrid War factors in the presently pro-American countries of insular ASEAN, so too could it do so in Vietnam if Hanoi doesn’t behave as “loyally” as Washington envisions it to be. One of the possible ‘symptoms’ of an assuredly sovereign state policy would be if Vietnam refuses to go along with some of the US’ CCC practices, for which it would obviously experience certain punitive repercussions. For this reason, it’s useful to explore what kind of destabilization potentials exist in Vietnam and game out the various means for how the US could possibly manipulate them if its newfound ally wavers in its strategic anti-Chinese commitment.

The six most realistic variables and scenarios can be categorized into those that deal with ethnic, regional, and social divides, and they will be examined in that order below. The ethnic groups function as support actors, while the social ones are expected to be the primary ones that take the lead in sparking the destabilization. The regional divide that’s explained below allows for a supportive and encouraging backdrop for ideological predisposed or indoctrinated individuals, and it also creates high hopes for those that are already entertaining anti-systemic notions.

Ethnic:

Khmer Krom

A little more than one million Khmer inhabit the southern reaches of Vietnam, and in the past their presence was used by Pol Pot as justification for Cambodia’s historic claims over the Mekong Delta. While the issue itself has largely receded in the decades since Vietnam put a stop to the aggression in 1979, it still remains possible that this demographic could be used in some manner to stir local anti-government discontent. As it currently stands, the Cambodian government is anathema to such suggestions, both out of multipolar pragmatism and stark remembrance of how disastrously it turned out last time around, but that doesn’t mean that a third-party actor (either the US directly or via one of its many NGO pawns) could do aggravate the situation instead.

There’s no practical way that the Khmer Krom could ever destabilize the whole of Vietnam, but a coordinated campaign could be implemented to use them as bait for provoking a military crackdown that leads to collateral damage against ethnic Vietnamese and/or international condemnation, especially if this scenario is mixed with a labor rights dispute of some sort. What’s pivotal in this example is that the Khmer Krom, separate in culture and language from the majority Viet ethnicity, are vulnerable to identity mobilization and thenceforth to being led into a bloody confrontation with the state, with the end result of the clashes (collateral damage, misleading media exposure) being more important than whatever short-term aims the ethnic group had been misled into coalescing around.

Hmong

Infamous for their collaboration with the US military during the Vietnam War, this scattered ethnic group poses a joint destabilization threat to both Vietnam and Laos. The Hmong are divided through dialect but united through geography, occupying a crescent of territory from northern Vietnam into northeast Laos. There are estimated to be over one million Hmong in Vietnam and less than half of that in Laos, so altogether they only form a recognizable percentage of the population in the latter (which has about 6.7 million people). The Hmongs’ significance derives from their identity in being a restive, anti-communist demographic with experienced cross-border travel between Vietnam and Laos, raising the tactical prospects that they could once more be used for drug and/or weaponssmuggling.

While the ones that remained in both countries after the US retreat have mostly been re-incorporated into society, if they were to resort back to their illegal transnational practices (whether being contracted by an intelligence agency to do so or out of their own pursuit of profit), they could create some trouble in this rugged and underpopulated frontier despite their miniscule numbers. Strategically speaking, any eruption of instability in Laos could then more easily spill over into Vietnam, with the Hmong communities once more plying their militant trade across the border and potentially arming distressed factory workers that are preparing for a local, regional, and/or nationwide uprising. Just like with the Khmer Krom, the Hmong by themselves are not in any position to destabilize Vietnam aside from being an isolated nuisance, but if their specific on-the-ground advantages are utilized in a certain manner, then they could be used as a force multiplier in any larger unfolding scenario.

Degar/”Montagnard”

Degar people areal

These mutually synonymous terms are used to refer to the native people of the Western Highlands. These Christianized tribal groups were allied with the French and US forces during the First and Second Indochinese Wars, and in terms of geopolitical importance, they abut the country’s borders with Cambodia and Laos and are located at a critical position in the country’s south. They have a history of rebelling against all aspects of Vietnamese rule, be it from the former South or the current reintegrated state, and they partook in a low-intensity anti-government insurgency that wasn’t disbanded until 1992.

The Degar join the likes of their fellow Khmer Krom and Hmong minority compatriots in being unable to affect significant disturbances on their own (especially with the current Cambodian government being unwilling to offer them any type of sanctuary to do so), but having the opportunity to maximize the potential of other destabilization scenarios if their actions are coordinated in sync. For example, if the 2001 “land rights” unrest and 2004 Easter protests (both of which were instigated from abroad) were to repeat themselves in some form concurrent with violent labor disputes elsewhere in the country, then it could possibly offset the authorities and create an opening for asymmetrical advances such as a renewed insurgency.

Furthermore, Degar destabilizations could ultimately lead to a large refugee flow into Cambodia if they end up failing, and this carries with it a risk to the Kingdom’s overall balance. The northeastern provinces bordering the Western Highlands are rural and mostly underpopulated, so it’s possible that this demographic could exploit the feeble governance there in order to set up anti-Vietnamese training camps. For now, at least, this doesn’t seem likely at all, but if Phnom Penh were in the midst of putting down its own anti-government riots (likely initiated under the cover of a labor revolt and to be explained in the relevant section), then it could be expected that this might occur to some extent.

Regional:

The days of a distinct division between North and South Vietnam are long gone, but certain socio-cultural differences still remain between the two. The reunification of the two entities after 1975 was fraught with many challenges, but none so more difficult than integrating the formerly capitalistic market of the South into the state-controlled system of the North. After experiencing some economic turbulence related to this undertaking and feeling the winds of American-supported global change that were sweeping across the world, the Vietnamese authorities decided to progressively open up their economy through the 1986 Doi Moi reforms. What’s ironic about this is that it represented an about-face for the communist state, which had just gone through great lengths to implement a strict top-down system in the South, but only to retreat from this policy about a decade later.

Other than some of the global and structural factors that were at play and exerting an undeniable impact, it’s unmistakable that Southern-based liberals also had a role over this decision. It’s not to insinuate that they had any ulterior motives in doing so, but that they genuinely believed from their experience that the economic model previously in place in South Vietnam was relatively more efficient than the one that they were later ordered to transition into by the North. No matter the degree of influence that the Southern liberals had over initiating the Doi Moi reforms, the fact remains that they were a comparative reversal of the previous system and an embrace of capitalist principles, the same operating structure that had earlier been in place in the South.

The pertinence of that period to the present is that the pro-Western economic thinking of that time is once more on the ascent in Vietnam, and with it, the possibility of a complementary pro-Western foreign policy. The last time that Hanoi followed the lead of Western influencing factors in the mid-1980s, it ended up unassumingly doing the West’s foreign policy bidding a few years later by withdrawing from Cambodia and Laos at the end of the Cold War. This time, Vietnam is on the verge of entering into the forthcoming TPP arrangement, and it’s playing a more militant role in the CCC hand-in-hand with this development. Whereas in the past it may have been contextually pragmatic for Vietnam to implement Doi Moi and remove its troops from the rest of Indochina, no such rationale can be evoked when it comes to the TPP and the CCC, both of which Vietnam is lunging into head-first.

It’s the author’s understanding that the 1980s Doi Moi and Cambodian and Laotian withdrawals symbolized the victory of the ‘spirit of the South’, or in other words, of certain policies that wittingly or unwittingly corresponded to Western preferences. In the same vein, joining the TPP and the CCC, and perhaps reinvigorating soft (economic) Vietnamese influence in Cambodia and Laos, accomplishes the same thing, albeit this time in full and witting compliance to the US’ regional vision. Therefore, the regional differences in Vietnam are less of a geopolitical nature and more of an ideological one, with the North (in ideas, not necessarily in terms of actual politicians) typically representing independent pragmatism, whereas the South symbolizes pro-Western bandwagoning. Ultimately, it’s the rivalry between these two camps that defines the current state of Vietnam’s international economic and political decision making, with the South obviously in charge at the moment. Should that change, then it’s likely that the US would fall back on utilizing the country’s ethnic and/or social destabilization variables in order to enact pro-Southern pressure on the government to bring it back in line with its CCC preferences.

Social:

Banned Religious Groups

One of the largest social disruptors in Vietnam could potentially come from the religious community in the country. Freedom of religion is guaranteed in Vietnam per the 1992 Constitution, and the country currently boasts a belief rate of around 46%, with 16% practicing Buddhism, 8% partaking in Christianity (be it Catholicism or Protestantism), and the rest following unorganized traditional beliefs. On the whole, these individuals are peaceful and apolitical, and it’s very rare for regular believers to encounter any sort of trouble from the state. The issue arises when adherents of banned Buddhist and Christian organizations such as the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam and the Vietnam Evangelical Fellowship, to name just two of them, illegally gather for services and proselytization practices. As a general rule, such groups are banned because they have a track record of engaging in political practices, and this is why they could present such a difficult challenge for the authorities if they go out of control.

To expand on this idea, so-called “religious freedom” is a powerful rallying cry for indoctrinated individuals and those susceptible to Western liberal-democratic thought. The general concept holds that governments should unrestrictedly allow any and all religions to be practiced, including obscure cult beliefs affiliated or unaffiliated with a major religion. Obviously, the individuals experiencing some type of state restriction on their religious practices (whether semi-conventional or outright cultish) are the ones most eager to reverse this state of affairs, and they may go about recruiting related co-confessionalists (as in the case of the banned Buddhist and Christian organizations) in order to assist them in this endeavor. At this point, what’s important to concentrate on is broader religious affiliation (be it Buddhist, Christian, or sympathy to both) being used as a mobilization issue for non-state agenda-driven actors. It doesn’t matter whether they use their socio-physical networks to agitate against state atheism and certain religious “restrictions” or any other object of protest, since the saliency lies in them simply organizing a critical mass of demonstrators that can ultimately disrupt the state’s stability.

To expand on this idea, so-called “religious freedom” is a powerful rallying cry for indoctrinated individuals and those susceptible to Western liberal-democratic thought. The general concept holds that governments should unrestrictedly allow any and all religions to be practiced, including obscure cult beliefs affiliated or unaffiliated with a major religion. Obviously, the individuals experiencing some type of state restriction on their religious practices (whether semi-conventional or outright cultish) are the ones most eager to reverse this state of affairs, and they may go about recruiting related co-confessionalists (as in the case of the banned Buddhist and Christian organizations) in order to assist them in this endeavor. At this point, what’s important to concentrate on is broader religious affiliation (be it Buddhist, Christian, or sympathy to both) being used as a mobilization issue for non-state agenda-driven actors. It doesn’t matter whether they use their socio-physical networks to agitate against state atheism and certain religious “restrictions” or any other object of protest, since the saliency lies in them simply organizing a critical mass of demonstrators that can ultimately disrupt the state’s stability.

Another critical component of this disruption strategy is that the religious-driven organizations and their affiliates could easily mislead their congregants to the conclusion that the only way for them to achieve their goals is through a violent overthrow of the state. They might point to “state-suppression” of their prior ‘activism’ as ‘evidence’ that working within the system is futile, thus compelling them to resort to Color Revolution and Unconventional Warfare practices (Hybrid War) in order to actualize their objectives when the time is right. While keeping their faith and religiously motivated end goal of regime change a secret, they can then take to recruiting other citizens to join their ‘dissident’ cause, most likely using a more encompassing and non-religious rallying issue such as workers’ rights to broaden their movement’s base. There’s a high chance that the majority of people brought into this fold might not be aware of the regime change purposes of the growing underground movement, being guided instead into thinking that they’re lending their support to a short-term, low-intensity protest movement about a seemingly ‘legitimate’ issue such as workplace safety. Unbeknownst to them, they’re actually being attached to a preplanned provocation that will inevitably result in violence, with the most ardent of the religious believers leading the way in sparking the militant conflict against the authorities.

To summarize the strategic framework that’s been articulated above, select members of the banned religious community in Vietnam and their supportive state-approved counterparts could quite easily band together in building a covert anti-government network. The more radical of the bunch could have already been convinced that the only way to affect the tangible change that they’re aiming for is to violently overthrow the government, and they’ll probably keep these intentions hidden from the more moderate members of the group. Even if this religiously affiliated organization sought to commence a destabilizing protest or an outright putsch, they’d likely fail without garnering enough supporters in advance. Since it can safely be assumed that the vast majority of Vietnamese are against a violent overthrow of their government, the only way to get them to physically support the regime change movement is to conceal its ultimate intentions, using more inclusive and broad-based language such as protecting/advancing labor rights and other non-religious issues that the majority of people could relate to in order to motivate them enough to come out in the street with their support. Even then, it’s not guaranteed that the scheme will appeal to enough people to make it effective, but the vehemence of the religiously motivated core organizers might be enough to give it some gusto.

Labor Rights Activists

The final Hybrid War factor impacting on Vietnam is also the most important, and it deals with the forthcoming institutionalized unionization in the country. One of the TPP’s precepts is that it mandatesthat Vietnam “legalize independent labor unions and workers’ strikes”, which in and of itself is certainly a welcome and positive gesture, but considering the regime change reputation that Washington has mustered, such a seemingly innocuous and well-intentioned prerequisite must defensively be viewed with the utmost suspicion. The author doesn’t intend to imply that all labor unions and workers’ strikes are potentially nefarious fronts for anti-government plots, but that under certain national conditions, there’s no doubt that they could be used as vehicles for advancing this agenda.

Vietnam has been dragged into a stereotypical dilemma – on the one hand, it needs to ensure and better workers’ rights and conditions, but at the same time, it needs to prevent its reforms from being abused by politically motivated actors. The crux of the problem is that the state waited so long to legalize these labor privileges, so that neither it nor the citizenry fully know what to expect. Hanoi is predicating its decision on the notion that this move will strengthen the government’s appeal and preempt socio-economic disturbances, but it might inadvertently end up weakening its power over the country and ushering in the same type of destabilization that it hopes to avoid.

Vietnam has been dragged into a stereotypical dilemma – on the one hand, it needs to ensure and better workers’ rights and conditions, but at the same time, it needs to prevent its reforms from being abused by politically motivated actors. The crux of the problem is that the state waited so long to legalize these labor privileges, so that neither it nor the citizenry fully know what to expect. Hanoi is predicating its decision on the notion that this move will strengthen the government’s appeal and preempt socio-economic disturbances, but it might inadvertently end up weakening its power over the country and ushering in the same type of destabilization that it hopes to avoid.

It’s inevitable that some of the unions will be co-opted by politically motivated elements or outright created as front organizations for them, yet their magnetic appeal and the popular acceptance that they’re expected to attain in Vietnamese society could indicate that an uncontrollably large segment of the population might vehemently be in support of them. As was earlier stated, there’s nothing inherently wrong with labor unions, but from the Hybrid War perspective, these groups are capable of gathering a large amount of people and assembling highly charged and easily manipulatable crowds that could be turned against the government. For example, if the unions and their supporters enter into a confrontation with the authorities (which is bound to happen in any organized labor dispute and/or strike) and provocateurs steer the situation along a preplanned scenario of violence, then the government reaction, no matter how justified it may be, could end up upsetting many people and enflaming anti-government sentiment.

There’s no clear-cut solution to handling this dilemma, and it’s obvious that both the state and the citizenry will have to learn as they go along. As regards the government, it needs to be able to identify the difference between a peaceful and legitimate labor-related protest and one which is on the verge of bubbling into an anti-government riot. It also needs to learn how to handle such incidents so that it doesn’t unwittingly do more harm than good in the tactics that it uses in breaking such demonstrations up. Alternatively, the public needs to get a handle on what sorts of behaviors are acceptable and which aren’t, and legitimate protesters need to learn how to police their own ranks to root out any provocateurs before they have the chance to act. The issue, as mentioned previously, is that neither side has the necessary experience to engage in this sort of civil society discourse without there being some unavoidable ‘growing pains’ such as Color Revolution infiltration and/or overreactive government crackdowns, both of which may serve to exacerbate preexisting anti-state sentiment and advance an externally directed regime change scenario.

Out of all of the variables discussed thus far, the “labor rights activist” one is the most all-encompassing, since it can conceivably envelop most of the working-age population within its ranks in some form or another. It doesn’t matter if they’re card-carrying members or sympathetic citizens, what’s important for the Hybrid War observer to realize is that the banner of labor rights is capable of organizing millions of people for the same shared objective, and that this critical mass of individuals can be guided against the government by adept practitioners of crowd-control psychology. Put another way, an untold number of regular, law-abiding, and well-intentioned citizens could get drawn into participating in what they believe to be a labor rights-focused protest, but only to in effect function as human shields protecting a radical core of urban terrorists that are intent on attacking the state. These political and/or religious radicals aim to provoke ‘incriminating’ and visually-documented police-on-protester violence that could then deceptively be disseminated as ‘truth’ and used to help recruit more people into the growing anti-government movement.

Along the same lines, nationwide or strategically focused regional labor disputes and strikes could be used to enact economic war against a targeted state from within, especially if the “union” has been co-opted by externally directed anti-government elements or is an outright front organization for them. In the circumstances where this is the case, the external actor (in mostly every imaginable situation, this would be the US and its intelligence/NGO apparatus) can inflict a two-for-one destabilization against their target. If the state is compelled to violently crack down on the rioters in order to restore order, then this could be manipulated against it via the social and physical anti-government ‘activist’ networks in generating even more dissatisfaction against the authorities; but at the same time, if the government doesn’t react and it allows the labor dispute and/or strike to continue indefinitely, then it risks experiencing a prolonged economic loss, especially if the factory, industry, and/or locale chosen for the disruption is of a strategic nature. In both instances, there isn’t a ‘win-win’ solution for the authorities, and they’re pressed to choose what they believe will be the lesser of two evils.

Putting the state on the defensive and forcing it to continuously react to these sorts of strategic lose-lose dilemmas are precisely the sort of tactics that Hybrid War practitioners specialize in. No matter what specific form they take or whatever particular issue the infiltrated or front organization claims to support at the time (be it labor rights, “free elections”, or the environment, for example), the indisputable pattern is that they always find a way to lure as many civilians into their ranks as possible in order to use them as human shields and ‘collateral damage’ for their preplanned anti-government provocation. The next step follows naturally enough, and it’s that the average citizen who hears about what happened (either on their own or via a nifty NGO-directed social media campaign) starts to lose faith in the government, largely unaware that what they had seen or read was totally staged and/or guided to occur by a foreign intelligence agency. The compound effect of this occurring on a large enough scale and with a certain context-specific frequency is that the population begins to either actively turn against the authorities and/or passively comes to accept the individuals that are fighting against them and whatever new state entity emerges in the wake of the current one’s possible defeat.

The Chances For A Hybrid War Crisis In Cambodia

Moving along in the book’s examination of Hybrid War threats in mainland ASEAN, it’s time now to turn to Cambodia, the first of the studied states to most likely be in the US’ regime chance crosshairs. Up until this point, the research was addressing countries where engineered Hybrid War scenarios were possible only in the event that their governments strayed from the general anti-China line (to varying degrees of rhetoric and form) that the US had ‘preferred’ that they abide by. Cambodia is a completely different matter altogether, since it’s the first ASEAN state that the book addresses in which bilateral relations with China are at an extraordinarily high level.

Although not a key node in Beijing’s primary ASEAN Silk Road from Kunming to Singapore, there are plans in motion to make it a supporting spoke, and the close ties between Beijing and Phnom Penh have drawn the ire of the US. Cambodia occupies a strategic position in China’s ASEAN strategy, and thereby it’s likely that it will experience some sort of renewed regime change destabilization in the coming future despite not being a chief transit state for Beijing’s transnational connective infrastructure designs. Additionally, the US is aware of the strategic regional advantages that it would gain from overthrowing Cambodia’s current government, and these calculations further increase the odds that long-serving Prime Minister Hun Sen might become Washington’s next regime change target.

This segment of the research begins by explaining the geopolitical significance that Cambodia has to China and the mainland ASEAN region. Afterwards it looks into the present political situation in the country and highlights the determined efforts of the ‘opposition’ in trying to topple Hun Sen. Finally, the last part draws attention to the most realistic Hybrid War scenario facing Cambodia, which just like in Vietnam, is the infiltration of the labor rights movement and its hijacked repurposing into the optimal regime change instrument.

Why Strategists Care About Cambodia:

The average reader might be perplexed about why ASEAN’s poorest state has any significance whatsoever in terms of Great Power planning, but the answer lies no so much in economics (although there’s plenty of opportunity there, as will later be explained), but in geopolitics. This is partly explained by China’s historical relations with Cambodia and general strategy towards ASEAN, but it’s also due to the demographic and state-to-state destabilization potential that Cambodia could potentially release towards its neighbors if it ever became a pro-American satellite state.

The China Factor

The most important issue to address in describing Cambodia’s geostrategic significance is its relationship with China. In the eyes of Beijing’s decision makers, Cambodia occupies a similar geopolitical importance to China as Serbia does to Russia, in that the strong partnership between the two allows the Great Power to ‘jump’ past a wall of obstructionist states. In the instance of mainland ASEAN, these historically had been Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, with the first two actually becoming pretty pragmatic towards China since the end of the Cold War. Even if those two diplomatic successes hadn’t been achieved, the relationship with Cambodia allows China to maintain a strategic presence in the Gulf of Thailand and have a firmly committed ally in the ranks of ASEAN. Most importantly in terms of China’s contemporary global strategy, Cambodia has proven to be the ideal testing ground for China’s overseas investment vision. The lessons that it learned by investing $9.17 billion in the nearby state during the period from 1994-2012, begun during the early days of China’s international rise and carried into the present, were obviously instrumental in helping it acquire the feel for managing similar overseas projects. Altogether, these experiences would blend together and contribute to forming the global One Belt One Road vision, with China’s initial investment forays in historically allied Cambodia undoubtedly playing an influential role.

From the Cambodian perspective, its leadership has historically looked to China as a type of ‘big brother’ in helping it hedge against Thailand and Vietnam. The historical memory of having been an object of rivalry between these two powers, and in one sense or another, the military basing ground for each of them at different times, weighs heavily on its decision-making imperatives. The collapse of the Khmer Empire brought Cambodia under the Siamese (Thai) fold for centuries, whereas the country was institutionally closer with Vietnam during the French imperial period. During the Vietnam War, its territory was continuously traversed by the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, and although the Vietnamese later liberated Cambodia from the genocidal Khmer Rouge, nationalist elements interpret the subsequent years as an unnecessary military occupation by an historic rival. Aside from the decade-long Peoples Republic of Kampuchea period from 1979-1989 when it hosted Vietnamese troops and was barred from dealing with China, there’s a clear continuity of pragmatic relations with its ‘big brother’ that was practiced by Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and then Hun Sen. Nowadays, other than the political-economic benefits that it reaps from its partnership with China, Cambodia also gains elevated prestige in ASEAN simply by being so closely aligned with Beijing, which has thus transformed the country from a diplomatic backwater to a premier outpost for regional states to engage China’s interests in the region.

From an overall perspective, Chinese-Cambodian relations are a win-win for both sides, and they’re about to be taken to a totally new level of mutual benefit through the Greater Mekong Region’s “Central Corridor” project. To remind the reader, this is one of the various connective projects in mainland ASEAN, with this particular route being a branch of the North-South Corridor through Laos. The Central Corridor branches off from Vientiane and slithers southwards down the country’s spine towards Cambodia, following the Mekong River along the way. This variation of the ASEAN Silk Road is important in its own right because of the potential that it has for deepening trade between China and Cambodia via an optimal unimodal system (solely ground-based as opposed to transshipment from boat to land), but it lacks the geostrategic capability of providing Beijing with an alternative route to the Indian Ocean. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor fully avoids the South China Sea headache and Strait of Malacca bottleneck, while the primary ASEAN Silk Road through Thailand has the possibility of doing so in the region of southern Thailand. This explains why Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand have a higher chance of falling victim to the US’ anti-Chinese plans (either in co-opting their elite or wreaking havoc) than Cambodia does, although Phnom Penh’s chummy ties with Beijing unquestionably puts it on the target list as well, albeit in a relatively lesser prioritization.

From an overall perspective, Chinese-Cambodian relations are a win-win for both sides, and they’re about to be taken to a totally new level of mutual benefit through the Greater Mekong Region’s “Central Corridor” project. To remind the reader, this is one of the various connective projects in mainland ASEAN, with this particular route being a branch of the North-South Corridor through Laos. The Central Corridor branches off from Vientiane and slithers southwards down the country’s spine towards Cambodia, following the Mekong River along the way. This variation of the ASEAN Silk Road is important in its own right because of the potential that it has for deepening trade between China and Cambodia via an optimal unimodal system (solely ground-based as opposed to transshipment from boat to land), but it lacks the geostrategic capability of providing Beijing with an alternative route to the Indian Ocean. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor fully avoids the South China Sea headache and Strait of Malacca bottleneck, while the primary ASEAN Silk Road through Thailand has the possibility of doing so in the region of southern Thailand. This explains why Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand have a higher chance of falling victim to the US’ anti-Chinese plans (either in co-opting their elite or wreaking havoc) than Cambodia does, although Phnom Penh’s chummy ties with Beijing unquestionably puts it on the target list as well, albeit in a relatively lesser prioritization.

Transnational Ethnic Trouble

The Khmer ethnic majority in Cambodia are a very proud people, infused with the civilizational glory of the ancient Khmer Empire. Accordingly, they’re also very patriotic, and their manifestations of pride could sometimes translate into nationalist demonstrations that put Thailand and Vietnam in an uncomfortable position. The reason that Cambodia’s neighbors feel uneasy at the exercise of Khmer patriotism is because they have their own Khmer minority within their borders, a legacy that nationalists have tried to exploit by attributing it to colonialism. In the case of the Thailand, these are the Northern Khmer that inhabit the northeastern region of Isan and live close to the Cambodian border. They constitute around a quarter of the population in Buriram, Sisaket, and Surin provinces. There are also scattered segments of the Western Khmer living in Chanthaburi and Trat provinces, although they have less of an impactful contemporary presence than in Isan. All told, it’s estimated that there are a little over one million Khmer living in Thailand. The situation with the Khmer Krom in southern Vietnam was already discussed in the earlier section about that country’s Hybrid War vulnerabilities, but to revisit the details for a moment, there are also about one million Khmer living there as well.

The geographically contiguous presence of ethnic Khmer diaspora living in the Thai and Vietnamese border regions means that a nationalist-driven Cambodia could pose a serious threat to the region’s stability. At the moment, it’s extraordinarily unlikely that Hun Sun would ever proceed down this destabilizing path, but in the event that he’s overthrown by a Pravy Sektor-like band of ultra-nationalists, it’s foreseeable that this demographic variable could become a complication in Cambodia’s bilateral relations with each of these states. If history is an indication, then a future nationalism-obsessed government might follow in the Khmer Rouge’s footsteps and stage aggressive border provocations against Vietnam, possibly to the point of tempting Hanoi to launch a retaliatory strike to snub out the threat just as it did back in 1979. Drawing a parallel to the present, this might turn out to be a Southeast Asian variation of the “Reverse Brzezinski” stratagem, with the entire provocation predicated on the intent of dragging Vietnam into a quagmire (in this scenario, possibly as punishment for bettering relations with China).

Using these strategic principles, the same concept can actually more realistically be applied towards Thailand in the Khmer-populated areas of its already distressed Isan region. Bangkok has been rapidly warming up to Beijing since the 2014 military coup and is now an integral transit state for the ASEAN Silk Road, thus meaning that any future Khmer-nationalist government in Cambodia would most likely be directed or implicitly guided by the US to targeted Thailand before Vietnam. The only thing that needs to happen to turn this Hybrid War projection into an actual plan is for an ultra-nationalist opposition movement to seize power in Phnom Penh just as they did in Kiev two years ago, most likely following a similar template of urban terrorism as their pro-American predecessors on the other side of Eurasia. In fact, such a possibility is actually being actively prepared for, the specifics of which will be explored more in-depth when the research discusses the internal political situation in Cambodia.

Border Rumblings

Aside from the asymmetrical destabilization that a hyper-nationalist Cambodian government could bring to its Thai and Vietnamese neighbors, there are also more conventional dangers that would go with this type of American-imposed government as well. As the reader likely realized by this point, Cambodia hasn’t always had positive relations with its two largest neighbors, and these have also manifested themselves into border disputes, the most recent and acute of which is the one with Thailand. The two countries almost went to war in 2008 over a disputed patch of land right near the Preah Vihear Temple in northern Cambodia. The reasons for the disagreement extend well past the physical territory in question and broach the larger historical and cultural issues, but the immediate root of the problem was the use of differing imperial-era border maps to support either case. The problem was eventually settled in Cambodia’s favor by the International Court of Justice in 2011, but because of the broader historical-cultural disagreements at play and the potential for a Khmer-nationalist Cambodian government to aggravate the situation with Northern Khmers, there’s a plausible chance that Phnom Penh might render irredentist claims against Thailand one day. Adding a branch to this scenario, the US might extend some form of outward or implicit diplomatic support for this initiative in order to pressure the Bangkok authorities and incite grassroots reactionary violence against the Northern Khmer in Isan.

Border marker No.314 between Vietnam and Cambodia.

The border situation with Vietnam hasn’t been as dramatic as the one with Thailand since the time of the Khmer Rouge, and currently there aren’t any feasible scenarios that it could apply against its eastern neighbor. The Khmer Krom are vastly outnumbered in southern Thailand when compared to the majority ethnic Viet, unlike the situation in the underpopulated provinces of Isan where they form a critical mass concentrated nearby the border. The prospective problem, then, isn’t so much ethnic irredentism (which is logically impossible to pull off against Vietnam), but a militant dispute over their recently delineated border. Historic flukes and random kinks along their frontier had long marred bilateral relations after the Vietnamese withdrawal from Cambodia, and even now, the border demarcation issue been exploited by the nationalist opposition in the latter in an attempt to score political points. Sam Rainsy, head of the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNPR) and the country’s main opposition leader,criticized Hun Sen for allegedly ceding land to Vietnam. His politically ally, Senator Hong Sok Hour, was arrested in August 2015 for presenting a forged government document that purportedly ‘proved’ Rainsy’s accusation, and the opposition leader himself was later issued his own arrest warrant in early January 2016 for involvement in the case. By that time he had already fled to France to avoid doing jail time for an unrelated defamation offense, but the fact that this issue has continued to bubble indicates that Rainsy may militantly act on his supposed claims if he ever succeeds in violently seizing power.

King Of The Cambodian Political Jungle:

The mentioning of Sam Rainsy is a perfect time to transition the research into discussing the internal political setup in the country. In a sense, it can read as a lead-up to what most likely will be a forthcoming Color Revolution attempt sometime between now and the July 2018 general elections. There are only two main players – Prime Minister Hun Sen and opposition leader Sam Rainsy – but only one can be king of the Cambodian political jungle.

Hun Sen

Cambodia’s prevailing leader has been in some capacity or another of the premiership since 1985, making him one of the world’s longest-serving heads of state. He was briefly a member of the Khmer Rouge before defecting to Vietnam, after which he reentered his homeland following its liberation by the Vietnamese military. He became Prime Minister in 1985 and served under the Kampuchean People’s Revolutionary Party, which later rebranded itself as the Cambodian People’s Party in 1991 and continues to hold power to this day. Hun Sen was almost booted from the government after losing the disputed 1993 elections, but after protesting the result and threatening that he’d lead the eastern part of Cambodia to secession, an agreement was reached whereby he’d serve in the position of co-Prime Minister.

His counterpart Norodom Ranariddh attempted to clandestinely seize power in 1997 through the use of covertly infiltrated Khmer Rouge and mercenary units to the capital, but Hun Sen was able to preempt the coup and stage his own countermoves that removed his rival from power and solidified his sole leadership. The next and last threat to his premiership came during the aftermath of the 2013 elections, whereby Sam Rainsy and his newly formed Cambodian National Rescue Party clinched 44.46% of the vote compared to Hun Sen and the Cambodian People’s Party’s 48.83%, which prompted Rainsy to accuse the authorities of fraud. The resultant protests descended into riotous behavior and closely resembled a Color Revolution attempt at times, but the drama was officially resolved when both parties agreed to a parliamentary power-sharing proposal on 22 July, 2014. Still, the close election results and the regime change behavior that was exhibited for a prolonged period afterwards indicates that a repeat of such events is very likely to happen in 2018, if not beforehand.

Looked at more broadly in an international perspective, Hun Sen is an adept pragmatic, skillfully able to maneuver his country between its two historical rivals and still retain the dominant political position within his country. Although he began his career as being ardently pro-Vietnamese during his premiership of the People’s Republic of Kampuchea, he moderated his approach the moment that his nominal ally’s military forces departed from his country. While never taking any anti-Vietnamese moves, he then swiftly sought to replace his former patron’s role with that of China, as has been the historic post-independence tradition of most Cambodian leaders. This decision was made on geopolitical grounds in hedging against both Vietnam and Thailand, although not doing so in an aggressive security dilemma-like manner that would jeopardize profitable relations with each. Consequently, he was able to retain his country’s friendship with Vietnam while making positive inroads with Thailand, and his partnership with China allowed Cambodia to secure its strategic independence and safeguard its decision-making sovereignty in what otherwise could have been a complicated geopolitical situation (especially after having just emerged from a ravenous US-supported civil war).

Sam Rainsy

Cambodia’s main opposition leader is the son of Sam Sary, one of the organizers of the Dap Chhuon Plot. Also known as the Bangkok Plot, this failed 1959 coup attempt sought to remove Sihanouk from power and is suspected of having been assisted by the CIA. Rainsy moved to France in 1965 and remained there for 27 years until 1992, after which he returned to his homeland and became a member of parliament. Since then, he has consistently remained involved in politics and founded the Khmer Nation Party in 1995, before changing its name to the Sam Rainsy Party in 1998. It’s interesting to note that he initially chose nationalistic name for his organization, which corresponds to the thesis that his opposition movement seeks to capitalize on such sentiment and may plan to take it to a destabilization international extent against Thailand and/or Vietnam if he ever attains full power.

Rainsy’s own actions attest to his nationalist bent, since he was arrested in 2009 for encouraging villagers to destroy border markets along the Vietnamese frontier, for which he was found guilty in-absentia for inciting racial discrimination and intentionally damaging property. He was pardoned by the King in July 2013 and returned that month to run in the general elections under the newly formed Cambodian National Rescue Party, a merger organization composed of his namesake party and the “Human Rights Party”. He eventually lost the vote and used his defeat as a rallying cry for organizing a Color Revolution attempt to seize power, which as was mentioned, ended up diffused after a parliamentary power-sharing proposal was agreed to.

True to his nationalist ‘credentials’, he continued to agitate that Hun Sen was apparently ‘ceding’ land to Vietnam, and he worked hand-in-hand with his political ally Senator Hong Sok Hour in having the latter produce a forged government document ‘proving’ this outrageous charge. His sidekick was soon arrested, and when Rainsy’s own parliamentary immunity was stripped from him and a warrant issued for his arrest during a visit to ‘supporters’ tin South Korea, he opted to evade the courts and currently remains abroad. Days before, he had gone on social media to intimate that Suu Kyi’s electoral victory forebodes well for what he believes will be his own forthcoming one in Cambodia, seemingly confirming that he too might also have been groomed by the CIA for future leadership. Overall, in assessing Sam’s political strategy, it’s evident that he has repeatedly gone out of his way to emphasize Khmer nationalism, which for the reasons described in the previous section, could end up being very destabilizing for the region if he ever succeeds in seizing power.

Constructing Cambodia’s Next Regime Change Scenario:

Rainsy The Rascal

Wrapping up the research on Cambodia, it’s now time to finally address the most likely scenario in which Hun Sen’s government could be overthrown. Sam Rainsy, like has been earlier described, is a clear nationalist and has sought to fuse his aggressive ideological rhetoric and provocations with Color Revolution tactics. His near-victory in the 2013 elections demonstrates that there’s a sizeable proportion of the population that agrees with him, although not quite enough to democratically legitimize his leadership aspirations. Rainsy will face arrest due to his two outstanding warrants (one for defamation and the other for his involvement in Senator Hour’s forged government documents case) if he returns to Cambodia, and Hun Sen has recently said that he’d “cut off [his] right hand” before he allows his rival to be pardoned again. In all probability, he’s likely to do whatever it takes to make sure that Rainsy doesn’t come back to Cambodia before the July 2018 elections, seeing as how he so bluntly put his entire reputation on the line through his dramatic threat.

Thematic Backdrop

What will probably happen then is that Rainsy will become a type of political symbol either through his ‘self-imposed exile’ (as he styles it) or the ‘political martyrdom’ that would result in his return to Cambodia. If he chooses the latter, it might be a lot easier to stir the Color Revolution pot and paint him as following in the footsteps of Tymoshenko or Suu Kyi, two of his regime change predecessors whose imprisonment catapulted them to global (Western) media stardom. No matter how it occurs, it’s certain that the Color Revolution movement will aim to socially precondition both the Cambodian masses and the foreign media into viewing the upcoming vote as a battle between a pro-Chinese (and possibly even falsely slandered as a pro-Vietnamese) “dictator” and a pro-Western “democrat”, bringing the tiny Southeast Asian state into the forefront of global attention. By that time, the Color Revolution infrastructure would be in place and the opposition can then commence their regime change operation, knowingly taking it as far as urban terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, thus representing the latest Hybrid War battleground.

Tactical Considerations

Be that as it may, the scenario can actually be fast-forwarded and deployed before the elections. Like with the newer Color Revolution templates that have been experimented with across the world, a concrete “event” such as a ‘disputed election’ or some other conventional rallying cry need not actually happen in order to spark the premeditated insurgency. What’s most important is that the necessary social infrastructure be capable of gathering large crowds of ‘human shields’ (civilian protesters) in order to protect a small core of violent provocateurs and engineer what can later manipulatively be made to appear as a “bloody government crackdown” against “peaceful protesters”. While nationalism is visibly a strong unifying force in Cambodian society, patriotism is equally as strong, and even though these two could clash (manifested by anti-government and pro-government demonstrators, respectively), the patriots might neutralize the disruptive “nationalists” and spoil their plans for a larger uprising. Along the same lines of thinking, a minor border spat in one of the frontier villages might not be enough to motivate people in the capital to come out to the streets in protest, especially since they have to worry about their own mouths to feed in ASEAN’s poorest state.

Labor Unions’ Unifying Role

That last point is actually the most important, and it’s precisely the one that’s capable of bringing large segments of the population out to protest against the government. Unlike in Vietnam, labor unions are already legalized in Cambodia and have played an active role in the country’s post-civil war history. The threat of labor disturbances has become increasingly common in the past few years, and garment workers recently prevailed in pressuring the government to once more raise their minimum wage in October 2015, this time to $140 a month from the previous $128 that they succeeded in gaining the year prior. To put this into context, the minimum wage had earlier been $80 a month in 2012, before being raised to $100 a month for 2014 prior to the aforementioned increases, all of which were the result of threatening labor strikes and engaging in selective clashes with police. Just like the author argued in the preceding analysis for Vietnam, there’s nothing at all inherently wrong with an organized labor movement that agitates for worker’s rights, but the danger presents itself when these organizations are exploited by politically minded actors working for regime change ends.

Hun Sen is the Prime Minister of Cambodia.

Unleashing The Dogs Of Hybrid War

In the prospectively forthcoming scenario for Cambodia, labor rights activists take center stage in leading a renewed anti-government movement, perhaps even before the July 2018 elections. They may either do so independently as part of their strategy to continuously raise the minimum wage, or they might craft a provocation in order to prompt a “government crackdown” against the “peaceful protesters”. Additionally, if Hun Sen accepts Washington’s offer to join the TPP but then gets cold feet like Yanukovich did with the EU Association Agreement, then that event in and of itself might be the spark needed to ‘justify’ the preplanned anti-government movement. No matter which route is finally decided upon, the end result is that the labor movement, particularly one which involves the country’s 700,000 garment factory workers (responsible for $5.8 billion in exports for 2014), takes the leading role in opposing the authorities.

This critical mass of individuals could then enact or threat to enact a paralyzing strike that would cripple the country’s economy and immediately cast it as an unpredictable and unstable place to do business in. The nationalist appeal of this campaign would be maximized if it’s coordinated in such a way as to target Vietnamese business, which account for $3.46 billion worth of projects in Cambodia and are the country’s sixth largest investor.

Expectedly, the ‘labor protesters’ will link up with the Cambodian National Rescue Party to create a unified front against Hun Sen, and the combined sum of their efforts might realistically be enough to topple the government. The only alternative in such a case would be large-scale state-inflicted violence, which even if it’s done in the interests of self-defense and the preservation of overall peace and harmony, could be damage the authorities’ legitimacy to the point of unwittingly engendering even more anti-government sentiment. Worse still, Western countries could pull out their investments and cooperate with ASEAN in sanctioning Phnom Penh. In this dire scenario, Hun Sen hangs on to power by a thread and the consequent economic warfare that’s launched against the country is impactful enough to lead to his government’s dissolution within the next few years.

To be continued…

Andrew Korybko is the American political commentator currently working for the Sputnik agency. He is the post-graduate of the MGIMO University and author of the monograph “Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach To Regime Change” (2015). This text will be included into his forthcoming book on the theory of Hybrid Warfare.

PREVIOUS CHAPTERS:

Hybrid Wars 1. The Law Of Hybrid Warfare

Hybrid Wars 2. Testing the Theory – Syria & Ukraine

Hybrid Wars 3. Predicting Next Hybrid Wars

Hybrid Wars 4. In the Greater Heartland

Hybrid Wars 5. Breaking the Balkans

There is something profoundly wrong with the way we are living today. There are corrosive pathologies of inequality all around us — be they access to a safe environment, healthcare, education or clean water. These are reinforced by short-term political actions and a socially divisive language based on the adulation of wealth . . .

There is something profoundly wrong with the way we are living today. There are corrosive pathologies of inequality all around us — be they access to a safe environment, healthcare, education or clean water. These are reinforced by short-term political actions and a socially divisive language based on the adulation of wealth . . .