In the early morning hours of January 26, 1987, federal agents across Los Angeles charged into the homes of seven men and one woman and led them away in handcuffs. More than 100 law enforcement officers—city, state and federal—were involved. “War on Terrorism Hits LA,” read the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner.

The defendants were all pro-Palestinian activists, but it wasn’t clear what they’d been arrested for. Soon the government conceded it would not introduce criminal charges, instead seeking to deport the group by alleging material support to a communist organization—an ancient Red Scare statute that would soon be declared unconstitutional. The case quickly became a mess, and in the end, 20 years of legal wrangling would pass before a judge would call the case “an embarrassment to the rule of law.” But in the first days of the defense, the lawyers for the men who would become known as the LA Eight were turning over a greater puzzle: why their clients had been targeted in the first place.And then the document arrived.It was a small manila envelope. No return address. No note. Inside, a typewritten government memo, barely legible. The package had been sent to one of the attorneys for the LA Eight, who rushed it to Marc Van Der Hout, his co-counsel.

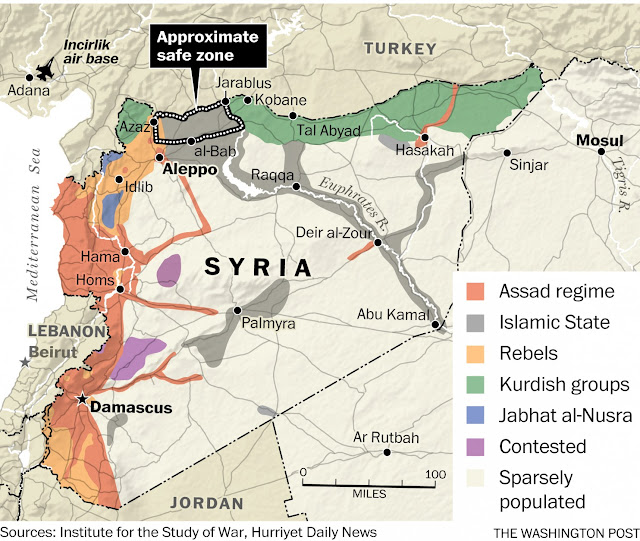

Van Der Hout was bewildered as he skimmed through it.The 40-page memo described a government contingency plan for rounding up thousands of legal alien residents of eight specified nationalities: Libya, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Tunisia, Algeria, Jordan and Morocco. Emergency legal measures would be deployed—rescinding the right to bond, claiming the privilege of confidential evidence, excluding the public from deportation hearings, among others. In its final pages, buried in a glaze of bureaucratese, the memo struck its darkest note: A procedure to detain and intern thousands of aliens while they awaited what would presumably become a mass deportation. Van Der Hout read the final pages carefully. The details conjured a vivid image of a massive detainment facility: 100 outdoor acres in the backwoods of Louisiana, replete with specifications for tents and fencing materials, cot measurements and plumbing requirements.

Four decades had passed since the U.S. closed its World War II-era internment camps, a disgraceful chapter when, without cause, the federal government forcibly relocated 120,000 Japanese Americans, imprisoning them across an archipelago of camps pocking the American South and West. Now, a working group in the Reagan administration was grasping for a similar-sounding measure. In 1987, the targets would not be Japanese Americans, but Middle Eastern aliens, lawful U.S. residents without the protection of green cards.

This wasn’t the far-fetched fever dream of an INS hothead; it was the product of careful deliberation, a process that had begun months earlier in the White House. In 1985, President Ronald Reagan, jarred by images of Americans killed on foreign soil at the hands of terrorists, sought a more aggressive tack to an emerging threat. It was the beginning of a shift from the twilight calm of the Cold War to a hotter, all-encompassing federal fixation on terrorism.

Large swaths of the federal government would be retrofitted with a counterterrorism agenda—from the Office of Management and Budget to the Department of Transportation. High on the list was the country’s immigration apparatus—or, as a phalanx of federal reformers began soon to call it, the first line of terrorism defense.

The document received by the attorneys for the LA Eight had originated from within the Immigration and Naturalization Service, then a division of the Department of Justice. The memo was hatched by Group IV of the INS’ Alien Border Control Committee. Van Der Hout had been in immigration law for years, but had never heard of it. In interviews 30 years later, the members of the ABC Committee insist that the document was not seriously considered—a bureaucratic fantasy with few meaningful ramifications—even as they defended the rationale that produced it.

In 1987, after the memo’s existence was briefly exposed, the ABC Committee was promptly terminated, the subgroup and the plan abandoned. But the ideas borne of the anxieties of the ’80s have gained new currency in the years since. In the wake of 9/11, America began detaining foreign nationals deemed threats to American safety—problematic though the legal grounds might be—in Guantanamo Bay. And with every fresh attack, at home or abroad, our demand for aggressive prosecution mounts. It is this fear that has underpinned the platform of Donald Trump—his promises of banning Muslims, blocking travel from countries compromised by terrorism and removing millions in a Herculean deportation scheme. Trump, however unwittingly, has drawn from much the same playbook as the plan once advanced by the ABC committee.

The existence of the committee and its long-forgotten work illustrates a truism of all government policy: old ideas never really die; they lie dormant in a frigid file cabinet, or buried in the Congressional Record, ready to bloom in a moment of political exigency.

One day recently, over lunch at a Virginia mega-mall, I placed the memo beside the plate of one former member of Group IV of the ABC Committee. How did it come to be? I asked him. He was pleasant, but indignant. The government is loaded with contingency plans like you wouldn’t believe, he told me. Best to stop worrying. “You said the department had to scrap this after it was leaked?” he asked. “If they withdrew this in 1986, they probably had something operational by 1992,” he continued. “They’d be foolish not to.”

***

In the late spring of 1986, Tom Walters sat in his office at the INS, scrawling out the details of a plan he barely understood. Days earlier, he had received an unusual directive from his superior Executive Commissioner, handed down to the Border Patrol: We need you to draw up a plan.

Since Walters had arrived at the INS headquarters in 1984 to oversee the formation of a Border Patrol tactical unit, he had already been asked to draw up a number of contingency plans. As far as he knew, none had come to fruition; INS had a habit of devising plans and shoving them into storage, rarely informing the agencies whose cooperation would be needed to execute them. But as he bulleted the details of this plan, Walters couldn’t recall a scenario as grandiose as the one he was tasked with writing. “This is an emergency response for dedicating border patrol resources,” Walters recalls being told by an Executive Commissioner who handed down the assignment. He pulled an old military plan, literally, off the shelf, outlining the use of an INS Detention and Deportation facility in Oakdale, Louisiana. Walters wrote out his adjustments in longhand, and handed them to a secretary to type up.

The ABC Committee had been authorized in June 1986, by the Department of Justice, but it was founded in spirit a year earlier, in June 1985 in the Oval Office. Underneath a patina of calm and domestic stability, Americans in the 1980s began to witness a creeping trend of political terrorism: 17 Americans killed by Hezbollah in Lebanon, a suicide truck bomber killed 241 at a U.S. Marines barracks in Beirut, more bombings in Kuwait, Athens and Madrid. Then, in June 1985, two gun-wielding Lebanese men affiliated with Hezbollah hijacked a San Diego-bound TWA 847, bearing 147 passengers and crew. The hostage crisis lasted 17 days; by its end, hijackers had murdered a U.S. Navy Petty Officer, Robert Dean Stethem, and tossed his body onto the tarmac.

“It was the first time the U.S. felt itself being actually targeted, even though most of the attacks occurred overseas,” says Buck Revell, then an Assistant Director of Investigations at the FBI. President Reagan was especially troubled by the murder of Stethem, and felt pressure to respond. In July, he signed a security directive to convene a cabinet-level task force on combating terrorism. The Task Force devolved into a working group of senior agency officials, charged with drawing up recommendations.

Almost immediately, they seized on immigration law as an untapped weapon against terrorism. “INS didn’t view themselves as part of the national security establishment,” says Revell, who served on the working group. During weekly meetings in a spacious conference room inside the Old Executive Office building, members of the working group became convinced that INS could be retooled to closely track incoming and outgoing aliens, receive intelligence shared by law enforcement, and speed up deportation proceedings.

Frustration with the glacial pace of deportations was informed by the Iranian Hostage Crisis, an event that haunted everyone in the working group. In 1979, after Iranian revolutionaries overtook the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, the Carter administration had mobilized INS to register the 75,000 Iranian college students in the United States—an undertaking mentioned throughout the memo that the ABC committee would later produce. In November and December of ’79, according to agency accounts, INS agents piled into cars and rolled into college towns. They met lines of Iranian students that stretched out cafeteria doors, waiting to register their names with INS officials seated behind fold-out tables. Students who evaded Carter’s order to register were detained and, overwhelmingly, released on bond, a setback that infuriated INS officials. Of the 60,000 Iranian students registered, 430 were deported. The revelation that INS lacked a method to track non-immigrant aliens other than road trips and registries that relied on the aliens showing up to be counted earned the agency the scorn of Congress.

If another mass registration were at hand, the working group would avoid the Iranian debacle. On January 20, 1986, President Reagan adopted the Task Force’s 44 recommendations in full, half of which still remain classified.

In November, six months after he wrote the plan for the Border Patrol, Tom Walters was summoned to the INS Commissioner’s windowless conference room, the nicest in the department, on the seventh floor of the Chester Arthur building in Washington. Around the dimly-lit conference table sat 13 low-level representatives from four federal agencies: The Justice Department, Customs, the U.S. Marshals and the FBI. At the head of the table sat the chair of committee, a young Walter “Dan” Cadman. Cadman had been tapped to lead Group IV of the Alien and Border Control Committee, the ABC subgroup that dealt with contingency plans. “Being a young and fairly new guy in the Central Office with little seniority, I got tagged because no one else wanted to sit around on what seemed to them to be a bureaucratic exercise,” Cadman told Politico Magazine via email.

Days in advance of the first meeting, the ABC committee’s members separately received the memo, titled “Alien Terrorists and Undesirables: A Contingency Plan,” the same document that would later leak to Weinglass and Van Der Hout. As the discussion began, Walters found himself in disbelief—not at the moral content of the meeting, but its technocratic scale. “I’d best characterize my reaction as shock,” he told me. Walters, like everyone else at the table, had never thought of INS as a terrorist-fighting organization; it was a domestic agency with a domestic charge. In its doling out of visas, perennial underfunding and quotidian attempts to weed out fraud at the border, INS shared more in common with the Social Security Administration than the Navy’s SEAL Team Six.

For the first hour, the men discussed the mission their superiors had given them: How to make INS a high-functioning weapon in the Reagan administration’s new war on terror. At the conference table in the Chester Arthur building, much of the fortnightly meetings were spent explaining definitions and concepts. Little time was devoted to discussing the merits of internment.

The memo begins with its summary recommendation: Banning incoming aliens from countries compromised by terrorism; deporting non-immigrant aliens through a section of the Immigration and Nationality Act relating to destruction of government property; rushing through new changes to the Code of Federal Regulations, and circumventing the typical rulemaking procedure to do so; expanding the legal definitions of international terrorism; and calling for intelligence-sharing to facilitate the deportations.

The INS’ multi-pronged proposals left little to the imagination, offering two options: a “general registry” and “limited targeting.” In its general registry scenario, the State Department would “invalidate the visas of all nonimmigrants” of the targeted nationalities, “using that as the first step to initiate a wholesale registry and processing procedure.” In its limited targeting scenario, the Investigations Division imagined a series of eight steps to expedite the deportation of the targeted nationalities. One was an executive order, requiring the FBI and CIA to share data with INS to locate alien undesirables and suspected terrorists. Another expanded the legal definition of international terrorism as a deportable offense; to speed the process, the measure would circumvent “proposed rule-making procedures, as a matter of national security.” The INS recommended holding aliens without bond, excluding the public from the deportation proceedings and convincing immigration judges to agree to those terms by referencing classified evidence.

A final note detailed “other program recommendations.” They included “summary exclusion” in the form of an executive order, imagining a president who suspended entry to “any class of aliens whose presence … was deemed detrimental to the public safety.” And it recommended a holding facility in Oakdale, Louisiana, a camp that could “house and isolate” up to 5,000 aliens.

It requested $2 million to develop the 100 grassy acres adjacent to the Oakdale facility with tents and fence materials, which would allow the site to be active on four weeks’ notice. “Community is receptive and has agreed to the location,” the section notes.

Toward the end of the document, an enigmatic military plan makes an appearance, punctuating the clipped prose and smeared typeface with a conspicuous ellipse: “Upon identification and activation of a military location,” it reads, “most of the various components of the South Florida Plan would then be operative.”

The South Florida Plan, according to intelligence officials and sources interviewed by Politico Magazine, was a little-known contingency plan for an emergency scenario inspired the 1980 Mariel Boatlift, when 125,000 Cubans fled the island in a months-long flotilla. From April through October, Cuban refugees, many of them felons and mentally ill prisoners, poured onto the beaches of southern Florida and the Gulf states. The immigration system groaned under the weight of a mass migration crisis, as prisons swelled and the INS was plunged into chaos.

The chaos in South Florida gave officials at the Department of Justice pause. Mariel had jettisoned a sliver of Cuban society. What would happen if the Castro regime collapsed? According to officials at the Justice and Defense Departments, to handle that exodus would require converting some of the largest military installations in the South into mass alien detainment centers, at least until the influx could be stemmed.

Willingly or not, Group IV of the ABC was now contemplating triggering the South Florida Plan. The ABC memo is never clear on the exact number of people targeted for internment and deportation: A Border Patrol preface identifies a target number “considerably less” than 10,000, while the Oakdale facility’s upper limit is proposed at 5,000. But buried in the memo, without preface or explanation, is a page that tallies 230,000 alien U.S. residents from eight targeted countries in the Middle East and North Africa. If internment and deportation proceedings were going to approach anything on that scale, the South Florida Plan was a viable option.

Dan Cadman remembers groaning at the sight of Walters’ memo in November 1986, when the ABC Committee first met. In Walters’ retelling, he simply delivered the memo he was instructed to. Through the group’s four meetings during November, December and January, little disagreement was aired.

“Our thought in [Investigations] was that once the other members had a chance to read the whole thing and come back together, collectively the group could kick that appendix to the curb in going forward with a final document,” Cadman told Politico Magazine in an email. “That didn’t happen because someone in the group—probably equally dismayed at the appendix—leaked the document.”

None of the men would discover the source of the leak—who at the table had sent the manila envelope to Weinglass. Usually, at the end of each meeting, the men would discuss the date they would reconvene. But at the last meeting, days before the leak, Cadman said the meeting time was TBD.

“Nobody called back,” says Walters.

***

As he looked over the leaked document in Los Angeles, Marc Van Der Hout was stunned.

The memo’s language lacks the circumspection of policy, barreling through one legal recommendation after another in a blaze of technocratic procedure. Yet at times, a glint of recognition shines through, moments in which the memo seems possessed of an awareness of its own transgressions. The memo notes that an attempt to register en masse lawful aliens of mostly Arab countries is “replete with problems in that it indiscriminately lumps together individuals of widely differing political opinions solely on the basis of nationality.” It quickly corrects: “There are, however, some advantages to the initiation of a registry”—one of which was the “benefit of being tested in administrative tribunals.”

Van Der Hout and a co-counsel, David Cole, now a professor at Georgetown University Law Center, became convinced that the memo was an uncanny outline of the government’s position and plan to deport the LA Eight—the “test case” which the document seemed to imply.

“They picked for arrest and deportation eight people who were essentially alien activists,” remembers Cole. “They sought to use classified evidence to detain them. [The memo] felt like a kind of blueprint for the case against our clients.”

The attorneys for the LA Eight were not the only ones to receive the leaked document. So did Stephen Engelberg, a reporter for the New York Times. His story on February 1, 1987, brought intense pressure on the INS. Beset by reporters at a news conference, William Odencrantz, a regional counsel for INS, was asked about the similarities between the case and the strategies described in the memo, and the seemingly political nature of the charges. “To use a football analogy,” Odencrantz told them, “we don’t care how we score our touchdown, by pass or run. We just want to get them out of the country.”

It was an astonishing confession. Cole, Weinglass and Van Der Hout launched a legal counterattack with the help of the ACLU. If they could prove the government had targeted their clients for their political beliefs and not due to ostensible unlawful behavior, they might get the case dismissed. Bringing their case to a district court, they won—though the decision would be overturned by the Supreme Court in 1998.

But the battle over the document roared on in the court of public opinion. And in Los Angeles, the leak of a federal plan to target legal U.S. residents based on their nationality caught the attention of another group: The Japanese American Citizens League.

The organization, whose members carried the memory of the internment camps, came to the public aid of the LA Eight, attending press conferences and distributing flyers in their defense. That is likely how the ABC memo passed into the possession of Norman Mineta, a California Democrat who represented the San Jose/Silicon Valley region in the U.S. House.

Mineta, now 84, can’t remember who first handed him the document. But he remembers the shock of reading it, a somber recognition.

In 1942, as a 6-year-old, Mineta and his family joined the roughly 120,000 Japanese Americans who were detained and forced from their homes and behind the barbed wire of internment camps hundreds of miles away. Mineta’s family was held at the Heart Mountain internment camp in Cody, Wyoming. Nationally, roughly two-thirds of those interned were citizens. The rest were aliens legally residing in the U.S.

At the time he received a copy of the ABC memo early in 1987, Congressman Mineta had been leading a charge for the Civil Liberties Act of 1987. The proposal would grant federal reparations to the survivors and families of those Japanese Americans interned during the 1940s. Speaking before a House subcommittee in April of that year, Mineta introduced the ABC memo into the Congressional Record, where Politico Magazine first found it.

Speaking from his living room in Annapolis, Mineta described reading the memo for the first time. He skimmed past the disembodied tone and reams of raw figures. His eyes then stopped on a single detail: the plan’s specification for the number of cots. “All I could think of was in 1942, having been forcibly evacuated and interned, we had to make our own mattresses,” Mineta says. “When we got off the train, the first thing we had to do was get this mattress ticking with hay and straw. And I’m reading this report, thousands of mattresses, cots, to be able to accommodate the people they had apprehended.”

Mineta’s testimony drove the final stake into the heart of the ABC.

“I believe it is vital to bring to the subcommittee’s attention that in recent months, a Department of Justice task force has proposed as legal and appropriate the mass round-up and incarceration of certain nationalities for vague national security reasons,” Mineta told the House subcommittee in his prepared statement. He quoted Solicitor General Charles Fried, who had told the Supreme Court earlier that year that the Japanese internment camps represented a “racial caste which was our shame.” “So this bill is not just about the past,” Mineta continued, referring to the reparations legislation. “It is about today and the future as well.”

Between 1987, when he entered the plan into the Congressional Record and preserved it for history, and when we spoke last month, Mineta says he hadn’t thought about the ABC memo—with one exception.

During the September 11th attacks, Mineta, then the Secretary of Transportation, ordered the FAA to ground every air carrier in the country. As a cabinet member in the line of presidential succession, he spent much of the next two days in a bunker. On the morning of September 13, the air in New York, Arlington, and Shanksville, Penn., still thick with smoke and ash, Mineta joined President Bush for a summit with the leadership of the House and Senate.

Toward the end of the meeting, Mineta recalls, House Democratic Whip David Bonior of Michigan expressed a fear to Bush: Our Muslim population in metro Detroit, Bonior told the president, is worried about rumors of targeting and round-ups. “David, you’re absolutely correct,” Bush replied. “We’re equally concerned about all that rhetoric.” The president extended a plaintive hand toward Mineta. “We don’t want to have happen today what happened to Norm in 1942.”

***

Fifteen years after President Bush implored the country not to relent to vengeful rhetoric, the country finds itself in familiar waters. The public debate is rife with talk of immigration bans, loyalty tests, intensified surveillance, deportations. Such ancillary ideas revive the one that never really disappears; it returns, it seems, every 30 or 40 years—from the Palmer Raids of 1919 to the camps of World War II, from the anxiety of the mid-1980s to the fear inherent in the 2016 race. But the pernicious resilience of mass internment became more clear when speaking to the men whose meetings and memos kept it alive.

In interviews over the past several months with Politico Magazine, former members of the ABC Committee struck a note of indignant stoicism about the 1986 memo—a brittle shell, earned from years toiling in the most political branch of federal policy. Didn’t I know anything about immigration, the men asked me. Didn’t I know how complex a time this was?

Walters, for his part, exuded an equanimity and glow in his post-retirement, despite the scrutiny he sensed a story about the document would bring him. I asked whether he thought the emotion from immigrant activist groups was warranted.

“I understand the view of the civil libertarian types on this, and they had some legitimate concerns,” Walters told me. But, he seemed to suggest, the group that was under siege was the INS. “The immigration service at the time, especially at the Border Patrol side, was feeling pretty overwhelmed and under-supported,” Walters said. A fantastical government agenda, handed down from on-high, was the last thing the Border Patrol wanted. But the the government gets the contingency plans it asks for.

One retired ABC member, who spoke to Politico Magazine on the condition of anonymity, came close to insisting the document wasn’t far off base. We met over lunch at an Italian chain restaurant in Virginia, where I propped the document astride his veal parmesan.

“Let’s be realistic,” he said. “If I’ve been told to watch out for bad Iranians or whatever—I do some work and quickly determine there’s 3,000 of these people in my county. So I’m going to go out and I’m going to follow 3,000 people? Oh, so I’ll start alphabetically?”

“Believe it or not, everything is not roses,” he said. “And ultimately, it takes force in order to enforce the laws.”

When I asked him about Mineta’s comments about the internment camps, he cocked his head and shot me a plaintive smirk. “Don’t you think that’s a bit hyperbolic?” he said. “If you really want to see genocide in the United States, go back and look to see what happened to the American Indian in California. That’s 1849.” He blinked, considering this for a moment. “Now, the Japanese were rounded up on the entire West coast. You don’t know. You’ve just been attacked—Hawaii! If the Japanese had sent troops, they would have had Hawaii.” He shakes his head, trailing off in a murmur. “We were wiped out. Very few ships got out.”

Most former ABC Committee members made some gesture toward disavowal, an important recognition that the document was not good policy. At the heart of this angst was the I-word: “It smacks of the dark period of U.S. history involving internment of Japanese Americans,” Cadman, the ABC chairman, wrote in an email. “What I regret is that because the project was killed and the group was disbanded, we didn’t get the chance to see the appendix officially disavowed as the work of the group progressed, however slowly that work was going.”

Still, the men of ABC retain a sense of common cause. They agree, for instance, that other branches of government—and civilians—simply don’t understand the tribulations of enforcing immigration law. In most of our conversations, there was a palpable nostalgia for some of the more benign proposals that the document laid out—a registration system, for instance; a way to track outgoing alien departures, not just entries; and, especially, a deportation process unmolested by the maneuverings of finicky defense counselors.

The LA Eight have been free for nine years, but Cole, their lawyer, takes little comfort. “This pattern repeats itself every time we face a crisis that creates fear,” he admonishes. “It’s easier to introduce these things if they’re targeted at foreign nationals than when they’re targeted at Americans. The government can say, ‘we’re talking away their liberties for your security.’”

As for the members of the ABC Committee, some would not rule out voting for Trump; they widely viewed his statements on immigration as flamboyant rhetoric, easy to be misinterpreted by a public that doesn’t understand hard truths, like their memo.