Shifting the Focus

So rank are the injustices wrought upon Okinawa, and so long continuing, that I am led to conjecture that the reason the world pays so little attention to the issues and makes such muted criticism of the governments largely responsible for the injustices must be that the situation is so complex and so little-reported as to defy understanding. Historians and political scientists pay close attention to the East China Sea, but tend to see it, and the military conflicts that occur around it, through the prism of the nation state. In what follows, I look at the present and recent past of the “Okinawa problem” through the prism of Okinawa, paying closest attention to how the Okinawan people see their recent past and present. I focus especially on the years of the (second) Abe Shinzo government (beginning December 2012).

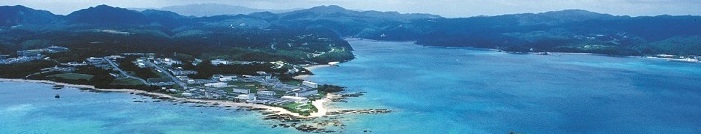

This essay is designed to chart a path and see a pattern in the struggles in the courts and on the Okinawan streets over recent decades, in the hope that it might serve as a kind of basic compendium on today’s Okinawa problem.1 How can it be that the Japanese state should now be attempting to sweep aside the overwhelming opposition of the Okinawan people in order to enforce the reclamation and construction works for a major Marine Corps facility at Henoko and for a string of Marine Corps “Osprey” landing zones in the vicinity of Takae hamlet in Higashi village, and that it by and large escapes international scrutiny for doing this, despite deploying high levels of discrimination and violence towards Okinawa in the process?

The “Okinawa problem” is complicated because it combines inter-state and intra-state elements. In its present, intense, form the antagonism between the Japanese nation state and the people and government of Okinawa dates to 1995 but its roots go back at least four centuries. For roughly half a millennium (1372-1879) these islands constituted the Ryukyu kingdom, self-governed and part of the China-centred “tribute system” world. Tribute missions plied the routes between Okinawa (then Ryukyu) and the China coast and ritual submission, evidently unmarked by violence or threat, seems to have generated less dissent than anywhere else in the then Sinic world. Twice, however, over these years, the mutually beneficial relationship was disrupted by violence and the threat of violence, on both occasions emanating from Japan, from the pre-modern state of Satsuma in 1609, and then decisively from the modern Meiji state in 1879, which simply incorporated the islands and abolished the kingdom.2

China protested, but those two interventions, taking place at moments of maximum Chinese weakness and disorder, the early 17th century decline of the Ming dynasty in the former case and the late 19th century decline of the Qing dynasty in the latter, were decisive. On both occasions the disruptive force came from Japanese militarism and imperialism, in the pre-modern form represented by Satsuma’s samurai and in the modern by the Meiji Japanese state. In the context of imperialist encroachment, civil war, and general decline of the 19th century in particular, China had no way to protest effectively against the Japanese severance of the China link and incorporation of Ryukyu as Okinawa prefecture. Negotiations towards a diplomatic agreement on the East China Sea border (and its islands, including not only Okinawa but also Miyako, Ishigaki and Yonaguni) in 1880-81 ended without resolution – although Japan had signalled its readiness to abandon the border islands – and eventually Japan dictated its terms on the region by victory in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-5. When Chinese voices in a much later era were raised to complain that there had been no negotiated diplomatic settlement of the East China Sea, it was strictly speaking correct.3

In 1945 Okinawa was the sole part of Japan that suffered the full force of American ground invasion and the “typhoon of steel” that pulverized the island, resulting in the deaths of between one-quarter and one-third of the population. As the war turned to occupation, and with the survivors in internment camps, the US enforced its claim to the prefecture’s best lands, upon which it then constructed the network of military bases that remain to this day, a process remembered in Okinawa as one of “bayonet and bulldozer.” In the peace agreement eventually signed at San Francisco occupation, the Japanese government, in part following the express wish of the emperor, encouraged the US to retain full control over Okinawa, with the result that it was 1972 before “administrative control” reverted to Japan. Even then, however, “reversion” was nominal, because the US retained its assets, the chain of bases, and extraterritorial authority over them, and even exacted a huge payment from Japan accompanying the deal.

During the 27-year period when Okinawa was completely under US rule, when there was no democracy and no mechanism for registering Okinawan protest, the American base structure was reduced in Japan proper but concentrated and expanded in Okinawa prefecture. 74 per cent of US base presence in Japan came to be concentrated on Okinawa’s 0.6 per cent of the national land. Over the 44 years since “reversion “ Okinawan governments have sought in vain to regain the sovereignty then lost, facing governments in Tokyo committed to faithful service of the US. As the Cold War was liquidated elsewhere, despite Okinawan expectations of liberation, it was retained and reinforced for them, and they were subject to persistent lying, deception, manipulation and discrimination.4 Okinawa became, and remains, to today a joint US-Japanese colony in all but name.

Richard Falk sets the “forgotten” Okinawan problem in comparative context:

“The tragic fate that has befallen Okinawa and its people results from being a ‘colony’ in a post-colonial era … captive of a militarized world order that refuses to acknowledge the supposedly inalienable right of self-determination. From a global perspective [Okinawa] is a forgotten remnant of the colonial past … In this respect it bears a kinship with such other forgotten peoples as those living in Kashmir, Chechenya, Xinjiang, Tibet, Puerto Rico, Palau, [the] Marianas Islands, among others.”[5]

Since the end of the Cold War, and especially under the two Abe Shinzo governments (2006-2007 and 2012- ) Japan’s defence and security systems have moved closer to full integration with those of the US. Major new facilities are under way for the US in Okinawa, Guam and the Marianas, and for the Japanese Self-Defense Forces on the Southwestern islands of Amami, Miyako, and the Yaeyama’s (Ishigaki and Yonaguni), while Abe proceeds towards setting up Japanese versions of the CIA and the Marine Corps (an “amphibious rapid deployment brigade”). In the first year of his second spell as Prime Minister, Abe alarmed Washington with his history and identity agenda (Yasukuni, comfort women, war memory) but gradually and under intense pressure he shifted his focus to economy and security, more than compensating, and setting aside for the time being the former. His security agenda depends on establishing Okinawa as joint American-Japanese military headquarters for the East Asian region.

Henoko, 1996-2012

Just 16 kms east of the capital, Naha, lies the bustling city of Ginowan, about one-quarter of which (including what should be its mid-city) is taken up by Futenma Marine Air Station. US forces first occupied the site around 70 years ago when the residents of the area had been rounded up into detention centres even before the formal Japanese surrender at the end of the war, and have continued to occupy it, in breach of international law (Article 46 of the 1907 Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War forbids occupying armies from confiscation of private property) even if with the consent, or encouragement, of the government of Japan, ever since. Okinawan resentment for long was simmering, but with the gang-rape of an Okinawan schoolgirl by three US servicemen in 1995, it came to the boil. A year later, in 1996, the governments of Japan and the US struck a deal: its main provisions were that Futenma Air Station would be returned to Japan “within 5 to 7 years” on condition that an alternative “heliport” facility for the marine Corps be provided, and that about half of the Yambaru forest area spanning Higashi and Kunigami villages, known to the Americans as Camp Gonsalves and serving as a Jungle Warfare Centre, would also be returned when additional “helipads” were substituted for those in the area to be returned.

As the 1972 “reversion” deal had cloaked “retention” of key US bases and extraterritorial privileges under the Status of Forces Agreement or SOFA, so this 1996 agreement for apparent “reversion” cloaked a significant expansion and upgrade of US military facilities. Henoko on Oura Bay was the designated site for a mega military complex, and the Yambaru forest for a supplementary chain of mini-bases.

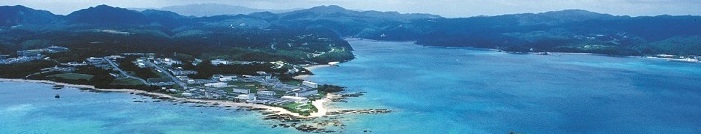

The “Futenma Replacement Facility” (FRF) agreed between the two governments of Japan and the US in 1996 would be a “heliport” built at Henoko on Oura Bay. Okinawans struggled by mass non-violent resistance, however, to such extent that the first (1999) design, for a demountable, offshore “floating base,” was cancelled in 2005 because, as then Prime Minister Koizumi put it, of “a lot of opposition”6 and, as was later learned, because the Japanese Coastguard was reluctant to be involved in enforcing the removal of protesters from the site for fear of bloodshed.7 In its stead the current (2006) design, for extension of the existing Camp Schwab Marine Corps site by substantial reclamation into Oura Bay, was adopted. It grew into today’s project to reclaim 160 hectares of sea fronting Henoko Bay to the east and Oura Bay to the west, imposing on it a mass of concrete towering 10 metres above the sea and featuring two 1,800 metre runways and a deep-sea 272 meter-long dock, constituting a land-sea-air base with its own deep-water port and other facilities. Smaller in area, it would be far more multifunctional and amount to a significant upgrade of the inconvenient and obsolescent Futenma.

Alongside the nearby massive Kadena US Air Force (USAF) base, the prospective Henoko facility would serve through the 21st century as potentially the largest concentration of land, sea, and air military power in East Asia, from which Japanese and US forces would combine to confront and contain China. The Abe government’s public and often repeated rationale for Henoko construction, moreover, is that it is the onlyway to accomplish reversion of the Marine Corps’ Futenma base.

However, though less densely populated than the Futenma vicinity, Henoko happens to be one of the most bio-diverse and spectacularly beautiful marine and coastal zones in all Japan, core to the “Amami-Ryukyu island zone that the Ministry of the Environment wants to promote as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It hosts a cornucopia of life forms from blue–and many other species of–coral (with the countless micro-organisms to which they are host) through crustaceans, sea cucumbers and seaweeds and hundreds of species of shrimp, snail, fish, tortoise, snake and mammal, many rare or endangered and strictly protected. In the seas the dugong and Japan’s only intact coral reef, and in the forest the Yambarukuina rail and Noguchigera woodpecker, have come to stand for all the creatures of the site vicinity.

When the Democratic Party assumed office in 2009, it found that its hands had been tied by a formal government to government agreement, the “Guam International Agreement,” negotiated in haste by Hillary Clinton to shield the Futenma substitution agreement from any attempt by a new government to revisit it.8 Months later, as Clinton had foreseen, Hatoyama Yukio came to office pledging to transfer Futenma “at least outside Okinawa” (saitei demo kengai). His efforts to accomplish this were feeble and the Guam International Agreement locked his government into submission. His failed promise to Okinawa nevertheless helped sowed seeds of hope that have underpinned the anti-base movement ever since.

By the time Abe Shinzo formed a government in December 2012, he faced an unprecedented Okinawan consensus, shared by the Governor, Prefectural and City Assemblies, prefectural chapters of the major national political parties (including Liberal Democratic Party and New Komeito), the two main newspapers and majority opinion in general (according to repeated surveys): it was time to wind back the US military presence, not reinforce it; Oura Bay had to be saved. If a new base was needed, it could be constructed outside Okinawa.

Futenma/Henoko from 2012

The government of Abe Shinzo, in his second term commencing in December 2012, faced this solid phalanx of opposition (in effect, the entire prefecture), but was determined nevertheless that Henoko would be built according to plan.9 In January 2013, an extraordinary Okinawan delegation, the Kempakusho, made up of the heads of Okinawan cities, towns and villages, and prefectural assembly representatives, called on the government in Tokyo to demand unconditional closure and return of Futenma, abandonment of the Henoko base substitute project and withdrawal of the MV-22 Osprey vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) Marine Corps aircraft. The delegation was headed by Naha City mayor, Onaga Takeshi, and many of its members were, like Onaga, staunchly conservative. Abe brusquely dismissed them and the coldness and abuse they experienced both from him and in the streets of Tokyo helped feed the identity politics that later became “All Okinawa.”

Thereafter, Prime Minister Abe concentrated on dividing and neutralizing that opposition. LDP party chief Ishiba Shigeru expressed what was probably the shared view within government when he wrote of the burgeoning protest movement in his blog (on 29 November 2013) that after all there was little difference in substance between vociferous demonstrators and terrorists.10 Opposition to any Oura Bay construction rose steadily, from 74 per cent in late April of 2014 to over 80 per cent in late August.11

Through 2013, Abe secured the surrender, first, in April of two prominent Okinawan Liberal-Democratic Party (LDP) Diet members, followed in December by the Okinawa chapter of the LDP itself and eventually by the Governor, Nakaima Hirokazu, who issued the necessary license for reclamation of Oura Bay as site for the base. Abe then turned to serious preparations for reclamation and construction, declaring, at the beginning of July 2014, just over half of Oura Bay off limits and initiating the preliminary boring survey. Despite the unfailingly non-violent character of the Okinawan movement, large numbers of prefectural riot police were sent against them, reinforced from late the following year by detachments from all over Japan. The riot police land force was matched at sea by the National Coastguard, whose armed vessels were commissioned to fend off the canoes and kayaks of protesters.

The surrender of the Okinawa branch of the LDP in December 2013, however, was not enough to break the prefectural opposition. Instead it was the Okinawan LDP that split, turncoats submitting to Abe outweighed by those who followed Onaga into what became known as the “All Okinawa” camp. The sense of betrayal stirred the Okinawan anti-base forces to a new level of mobilization. Through 2014, an entire prefecture voted against the national government’s plans (and rejected its blandishments) at successive elections and at multiple levels. In January, Nago City (which includes Henoko and Oura Bays, the designated new base construction site) returned as its mayor the anti-base (“no new base in this city whether on land or on sea”) Inamine Susumu, in the process rejecting the extraordinary offer by the LDP Secretary-General of a 50 billion yen “inducement” fund for Nago City development if only it would elect a pro-base candidate. In September, Nago returned an anti-base majority to the City Assembly. In November, Onaga Takeshi was chosen as Governor by an unprecedentedly large margin (380,820 to 261,076) over the turncoat Nakaima Hirokazu, after pledging to do “everything in my power” to stop construction at Henoko, close Futenma Air Base, and have the Marine Corps’ controversial Osprey MV 22 aircraft withdrawn from the prefecture. Then in December all four Okinawan constituencies in the lower house of the Diet returned anti-base candidates in the national elections. It was a decisive democratic rebuff to the government in Tokyo.

Early in 2015, the Okinawa Defense Bureau dropped 49 concrete blocks (each weighing between 10 and 45 tons), into Oura Bay as anchor for the works to come, causing damage to coral that was clear in photographs taken by naturalists and journalists. Onaga ordered them to stop (16 February) but declined to formally cancel the permit for rock and coral crushing issued by his predecessor in August 2014, despite strong urgings from Okinawan civil society and nature protection organizations. Inexplicably, he declared, “unfortunately it is not possible to make a judgement as to destruction of coral.”12 Although works were several times suspended during the year that followed due to fierce continuing Okinawan protest, typhoon weather, and the exigencies of elections, budgetary allocations continued to pass unchallenged, tenders to be let, landfill sought and allocated, workers hired. Abe repeatedly assured the US government that the works would proceed according to his plan, irrespective of Okinawan sentiment.

“All Okinawa” and Governor Onaga, 2014

From December 2014, therefore, Okinawa had a Governor and a prefectural assembly or parliament committed to stopping the construction works at Henoko and restoring Oura Bay. Yet, new governor notwithstanding, prefectural riot police and national Coastguard forces continued to crush protesters and government contractors bore into the bed of Oura Bay.

Onaga’s appeal to Okinawan mass sentiment was based on his “re-birth” as an avatar of “All-Okinawa” identity politics, transcending the categories of conservative and progressive, “left” and “right,” and proclaiming the principle of “identity over ideology.” Yet, the problem with that “All Okinawa” mantra is that identities are commonly multiple. Okinawan governor Onaga is both implacable opponent of the national government in certain respects and yet in other respects the quintessential, conservative local government Japanese politician. He is not only Okinawan but, like Prime Minister Abe, a lifelong (to 2014) member of the Liberal Democratic Party. While he poses a major challenge, rooted in identity politics, to the government of Japan (and beyond it, to that of the United States), it is not clear how far he can be expected to lead the prefecture down the path of resistance to his conservative colleagues and counterparts at the helm of the nation state. Whether Okinawan identity can trump ideology and generate a credible democratic politics remains to be seen.

Upon taking office as Governor, Onaga was shocked to find that major figures (Prime Minister, Cabinet Secretary, Foreign Minister) refused to see him. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga said bluntly, “I have no intention to meet him during [the remainder of] this year.”13 Defense Secretary Nakatani said (13 March 2015) it would be “meaningless.” That stance was of course not long tenable, but the hostility it expressed was palpable. At the Henoko site, where the sit-in at the gate of Camp Schwab began in July 2014, protesters were harassed and threatened. Ryukyu shimpo editorialized,

“As far as we know, the government has never unleashed such reckless disregard of the will of the people as we have seen at Henoko. … We wonder if there has ever been a case like this, where the government has trampled on the will of the overwhelming majority of people in a prefecture elsewhere in Japan. This action by the government evokes memories of the crackdown against peasants during the Edo period. … The Abe government seems to be in the process of moving from ‘dictatorship’ to ‘terror politics’.”14

The US authorities refused (for “operational reasons”) permission to the Governor to enter the site to conduct the survey he had promised to assess damage to the coral from the concrete blocks dropped into the sea-floor, and the government, brushing aside protest, resumed the process. In a particularly egregious act of violence, in March 2015 it sent in riot police to rip away the tent-like protection that had been put in place for a National Sanshin Day performance at Camp Schwab Gate by 20 Okinawan performers (on the Okinawan three-stringed instrument known in Japan as shamisen), leaving them to perform in the rain. On 12 March 2015, it began to bore into the sea floor from a gigantic drilling rig.15

Though Onaga’s support level remains high in Okinawa, there are nagging doubts about how he would reconcile his “All Okinawa” posture with his conservative record. Onaga has limited his differences with Tokyo to two specific demands: closure of Futenma without substitution (i.e., abandonment of the Henoko project), and withdrawal of the MV-22 Osprey aircraft, the subjects of the Kempakusho protest delegation to Tokyo that he led in January 2013. Onaga makes no secret of his support for the US-Japan Security Treaty and the base system (obviously with the exception of the Futenma substitution project), and he was silent during the summer of nation-wide protest against the Abe government’s secrecy and security bills in 2015, suggesting that he supported, or at least did not oppose, Abe’s controversial interpretation of collective self-defense and security legislation package.16 Onaga also remained silent on the Osprey-pad construction protest at Takae until the summer of 2016, and even then made no visit to the site and no attempt to assert his authority over the riot police who acted in his name, reserving his criticism for the reliance on force, the “excesses” rather than the act itself. When riot police reinforcements were sent from mainland Japan to enforce works at Henoko from late 2015 and at Takae from July 2016 they were sent under the provisions of the National Police Law (1954) at the request of the Prefectural Public Safety Commission, whose members are responsible to and nominated (or dismissed by) the Governor.17 It is one of the paradoxes of contemporary Okinawan politics that Onaga has not been subjected to any public demand that he attempt to exercise authority over prefectural policing, for example by cancelling or withdrawing the request for such reinforcements. At least in theory, he could dismiss any or all of its five members and appoint others who would represent Okinawan principles.18

Onaga could, however, be very forthright in making his prefecture’s case. While Abe and his ministers insisted that the Henoko project amounted to a “burden reduction” for Okinawa, that it was the only way to achieve Futenma return and that it was irreversible, Onaga spoke of an inequitable and increasing burden, building upon the initial illegal seizure of Okinawan land and in defiance of the clearly and often expressed wishes of the Okinawan people; of a struggle for justice and democracy and for the protection of Oura Bay’s extraordinary natural biodiversity, worthy, as he saw it, of World Heritage ranking. Onaga quoted the Okinawa Defense Bureau estimate of more than 5,800 kinds of biota in the Bay zone, (262 of them in danger of extinction), and referred to the sea around Henoko as being twice as rich in biota as the sea around Galapagos,19 and noted the likely environmental devastation that dumping into the Bay of 3.4 million dump-truck loads (20 million cubic metres) of soil and sand for reclamation would be likely to cause.20

The state under Abe has tended to adopt perverse or arbitrary readings of law and constitution, and in regard to Henoko it has relied on superior force and intimidation. It is certain that no other prefectural governor in Japan would ever refer to the national government in the way that Onaga does, as “condescending,” “unreasonable,” “outrageous,” (rifujin) “childish” (otonagenai) and even “depraved,” (daraku).21 Before the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva in September 2015, he accused it of “ignoring the people’s will.”22 He also complained about the government’s weakness in being “completely lacking in ability to say anything to America.”23 To the Prime Minister, Onaga said,

“Construction of Futenma and other bases was carried out after seizure of land and forcible appropriation of residences at point of bayonet and bulldozer, while Okinawan people after the war were still confined in detention centres. Nothing could be more outrageous than [for you] to try to say to Okinawans whose land was taken from them for what is now an obsolescent base [i.e. Futenma], the world’s most dangerous, that they should bear that burden and, if they don’t like it, they should come up with an alternative plan.”24

Judicial Proceedings (1) The Experts Report (2015)

To advise him on the legal and environmental questions arising from the consent given by his predecessor to the reclamation of Oura Bay, Onaga early in 2015 set up an advisory committee of experts, the “Third Party Commission on the Procedure for Approval of Reclamation of Public Waters for the Construction of a Futenma Replacement Airfield,” to identify possible flaws in the legal process that might warrant its cancelation.

The Commission’s report, on 16 July, amounted to an unambiguous finding of multiple procedural “breaches” (kashi) in the way the Nakaima administration had made its crucial December 2013 decision to approve the environmental assessment. It adopted the common expert view of the Henoko environmental impact assessment (EIA) process as “the worst in the history of Japanese EIA.”25 It found that “necessity for reclamation,” a crucial consideration under the 1973 revision to the “Reclamation of Publicly Owned Water Surfaces Act” (Koyu suimen umetateho, 1921), had not been established. Of the six specific criteria under Article 4 of that law for reclamation, the Henoko project failed on three. It did not meet the tests of proof of “appropriate and rational use of the national land,” proper consideration for “environmental preservation and disaster prevention,” and compatibility with “legally based plans by the national government or local public organizations regarding land use or environmental conservation.” It was also incompatible with other laws including the Sea Coast Law (1956) and the Basic Law for Biodiversity (2008). In short, the basis of the reclamation project was legally flawed.26 This opened the path for Onaga to cancel the reclamation license.

Following a one-month (August-September 2015) lull in the Oura Bay confrontation while a round of “talks” was conducted fruitlessly, the government reiterated (through the Minister of Defense) its stance that there had been no “flaw” in the license Nakaima had granted. It therefore ordered site works resumed. Its agents scoured the coastal hills and beaches of Western Japan to identify and place orders for millions of tons of soil and sand to dump into Oura Bay. It also ordered an additional 100-plus riot police (units with names such as “Demon” and “Hurricane”) from Tokyo to reinforce the mostly local Okinawan forces who till then had been imposing the state’s will at the construction site. Eventually, on October 13, Onaga formally revoked (torikeshi or canceled) the reclamation license.27

The national government, its warrant for works removed, temporarily suspended them, but the Okinawa Defense Bureau (OBD) formally complained to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLITT), protesting that there were no flaws in the Nakaima land reclamation approval of December 2013 and that Governor Onaga’s revocation of it was illegal, asking MLITT to review, suspend, and nullify that order under the Administrative Appeal Act.28 Onaga presented a 950-page dossier in which he outlined the prefectural case,29 but, following a cabinet meeting on October 27, MLITT Minister Ishii Keiichi duly suspended the Onaga order on grounds that otherwise it would be “impossible to continue the relocation” and because in that event “the US-Japan alliance would be adversely affected.”30 To Governor Onaga, he issued first (October 27) an “advice,” and then, days later (November 6), an “instruction” to withdraw the cancellation order. Onaga refused. On October 29, works at Henoko resumed, the government referring to them as “main works” (hontai koji), evidently in order to have them seen as a fait accompli, inducing despair and abandonment of the struggle on the part of protesters, even though the boring survey was still at that point incomplete and the outcome of the struggle far from determined.

On 2 November, Onaga launched a prefectural complaint against the Abe government with the Central and Local Government Disputes Management Council, a hitherto relatively insignificant independent review body set up in 2000 by the government’s Department of General Affairs. That Council took barely six weeks, to 24 December, to dismiss the complaint, without calling upon any evidence. Despite the fact that it would be hard to imagine anything that could better qualify as a dispute between those two wings of government, it ruled, mysteriously, that the complaint was “beyond the scope of matters it could investigate.”31

While this Disputes Council complaint was being heard, on November 17 2015, the national government (through the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, or MLITT) filed suit against the Okinawan government under the Administrative Appeals Act, alleging administrative malfeasance and seeking to have Onaga’s order set aside and a “proxy execution” procedure adopted.

The presiding judge in this “proxy execution” suit was Tamiya Toshiro. Tamiya had only taken up office in this court two weeks earlier, on 30 October, following transfer by the Ministry of Justice from the Tokyo High Court.32 There was speculation that his appointment, weeks before the government’s suit against Governor was lodged, might have been the result of bureaucratic/judicial collusion designed to ensure Okinawan submission to the base construction plan. There was no doubt that the government wanted at all costs to secure a court ruling that would confirm the MLITT minister’s reinstatement or “proxy execution” of the land reclamation approval. But beyond that, and with Judge Tamiya’s verdict still some weeks away at time of writing, it is impossible to go at this point.

On 25 December, the prefecture launched its counter-suit in the same Naha branch of the Fukuoka High Court, seeking to have the October ruling by the Minister set aside. The extraordinary nature of the conflict was thus evident as state and prefectural authorities sued each other over the same matters and in the same Naha court.

The prefecture insisted it was a breach of its constitutional entitlement to self-government for the state to impose the Henoko construction project on it unilaterally and by force. Onaga pointed to what he saw, on expert advice, as fatal flaws in the land reclamation approval process. He objected to the ODB’s use of the Administrative Appeal Act, for which purpose the state was pretending to be just like a “private person” (ichishijin) complaining under a law specifically designed to allow individual citizens to seek redress against unjustified or illegal acts by governmental agencies, and noted that, while the state sought relief as an aggrieved citizen it deployed its full powers and prerogatives as state under the Local Self-Government Law to sweep aside prefectural self-government and assume the right to proxy execution of an administrative act (gyosei daishikko). The state was in his view thus adopting a perverse and arbitrary reading of the law.

The state, for its part, argued that base matters were its prerogative, having nothing to do with local self-government, and being a matter of treaty obligations were not subject to any constitutional barrier. Abe spoke repeatedly of “Futenma return,” but only on condition that there was a substitute, and the substitute had to be in Okinawa, and in Okinawa at Henoko. That new base would be more multi-functional, more modern, and almost certainly permanent but, by his reasoning, its building would amount to a “burden reduction” for Okinawa.

Tamiya rejected applications by the prefecture to call expert witnesses on military and defense matters (who might dispute the need for a Marine Corps presence in Okinawa) or on the environment or environmental assessment law (who might challenge the compatibility of Okinawa’s unique bio-diversity with large-scale reclamation and militarization). The matter on which his court showed strong, even exceptional, interest was the securing of an explicit statement from Governor Onaga that he would abide by its ruling.33 In proceedings before the Tamiya court six months later (discussed below) this same pattern was apparent.

Judicial Proceedings (2) Wakai/Conciliation (2016)

As the flurry of writs and interrogatories continued, and the tense and sometimes violent confrontation continued between state power and protesting citizens at the reclamation/construction site, it was hard to imagine where ground for compromise might be found. Yet that is precisely what Chief Justice Tamiya ordered when, on January 29, 2016, he advised the disputing parties in the suit launched by the Government of Japan against Governor Onaga to consider an out-of-court settlement. He began with the following exhortation:34

“At present the situation is one of confrontation between Okinawa and the Government of Japan. So far as the cause of this is concerned, before any consideration of which is at fault both sides should reflect that it should not be like this. Under the 1999 revision to the Local Autonomy Law it was envisaged that the state and regional public bodies would serve their respective functions as independent administrative bodies in an equal, cooperative relationship (italics added). That is especially desirable in the performance of statutory or entrusted matters. The present situation is at odds with the spirit of this revised law.

The situation that in principle should exist is for all Japan, including Okinawa, to come to an agreement on a solution and to seek the cooperation of the United States. If they did this, it could become the occasion for positive cooperation on the part of the US too, including broad reform.35

Instead, if the issue continues to be contested before the courts, and even if the state wins the present judicial action, hereafter it may be foreseen that the reclamation license might be rescinded or that approval of changes accompanying modification of the design would become necessary, and that the courtroom struggle would continue indefinitely. Even then there could be no guarantee that it would be successful. In such a case, as the Governor’s wide discretionary powers come to be recognized, the risk of defeat is high. And, even if the state continued to win, the works are likely to be considerably delayed. On the other hand, even if the prefecture wins, if it turns out that the state would not ask for Futenma return because it insists that Henoko construction is the only way forward, then it is inconceivable that Okinawa by itself could negotiate with the US and secure Futenma’s return.”

Tamiya thus rebuked and warned the state that, unless it fundamentally changed its strategy, it was heading towards defeat. In particular he focussed attention on the 1999 revision to the Local Autonomy Act that turned the national-prefectural government relationship from instrumental (vertical, superior/inferior) to equal and cooperative. Tamiya went on to urge the parties to “conciliate” (wakai), offering two alternatives, “basic” and “provisional.” The “basic” solution would have Okinawa reverse its withdrawal of the reclamation permit in exchange for the Japanese government opening negotiations with the U.S. to have the new base

“either returned to Japan or converted into a joint military-civilian airport at some point within thirty years from the time it becomes operational.”

The inclusion of provisos for the defendant [prefecture] and the plaintiff [the state] to cooperate in the reclamation and subsequent operation [of the base] meant that this plan was predicated on the contested base at Henoko actually being built and provided to the Marine Corps, probably until at least the year 2045 (or indeed much longer, because there could be no guarantee as to how the Government of the United States would respond to any Japanese request at such a remote future date). There was nothing conciliatory or amicable about it. It was hard to see in such ideas any inkling of a solution. Nakasone Isamu, himself a retired judge, noted,

“the success or failure of diplomatic negotiation with the United States is contingent on the cooperation of a third party, namely the United States. In other words, the paragraph does not describe something that the Japanese government has the authority to execute freely. Thus it fails to adhere to the requisites of a term of settlement, and thus the settlement proposal as a whole lacks validity from a legal standpoint.”36

Under the “provisional” plan the state would stop site works, and the parties open talks towards a satisfactory resolution (enman kaiketsu) pending outcome of a judicial determination, which both parties would respect and implement. If the talks failed to achieve a solution, the government would then file a different, less legally forceful type of lawsuit to verify the legality of the permit withdrawal.

Although it was hard to see how negotiations in 2016 would accomplish more than the “intensive negotiations” of August-September 2015, or how fresh court proceedings would overcome the problems the judge himself alluded to, on 4 March the parties came, as directed by Tamiya, to an “out-of-court” or “amicable” (wakai) settlement.37 Site works were halted, both parties withdrew their existing suits under the Administrative Appeals Act and the state agreed to ask the prefecture under Article 25 of the Local Autonomy Act to cancel the order cancelling the reclamation license and agree to the matter being referred to the Central and Local Government Disputes Management Council in the event of its declining. Clearly Tamiya’s court saw such a suit as more appropriate to the formally equal relationship between the parties than the execution-by-proxy suit that the Abe government had chosen. The parties would discuss and seek “satisfactory resolution” pending the final outcome of judicial proceedings, and both would then abide by whatever outcome then emerged.

The fact that Judge Tamiya combined formal, procedural critique of the Abe government’ with support for its case, evident in this recommendation of a “solution” that involved construction of the very base that Okinawans were determined to stop, held ominous implications for the prefecture. The barb in the “Amicable Agreement” was the superficially innocuous “sincerity” provision eventually incorporated in Paragraph 9, designed to remove any possible further recourse to the courts once the Supreme Court comes to its decision. It read:

“The complainant and other interested parties and the defendant reciprocally pledge that, after the judgment in the suit for cancellation of the rectification order becomes final, they will immediately comply with that judgment and carry out procedures in accord with the ruling and its grounds, and also that thereafter they will mutually cooperate and sincerely respond to the spirit of the ruling.”38

Challenged in the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly on 8 March 2016 as to what this commitment to “cooperate and sincerely respond to the spirit of the ruling” meant, Governor Onaga explained his understanding that, although his October 2015 order might thereby be cancelled, and the Nakaima license restored, in respect of all other matters he would make “appropriate judgement in accord with the law.”39 He did not go into detail, but that would seem to mean that, even if defeated in court, he could still resort to his ultimate sanction – repeal of the Nakaima reclamation license (umetate shonin tekkai), going beyond the “cancelation” order he had issued in October 2014. Not only that but he could, and evidently would, refuse or obstruct requests from the state for detailed adjustments to the reclamation plan or engineering design.40 Nago City mayor Inamine has also made it clear on many occasions that he would follow suit.

Since the March 4 “amicable settlement” was drawn up and agreed in accord with court directives, it was neither “out-of-court” nor a “settlement.” Nor was there anything “amicable” about it. Under it the government shifted its case against Okinawa from the Administrative Appeals Act, where its position was procedurally weak, to the Local Government Act, where it might be stronger.

Japan versus Okinawa, 2014-2016 – Major Events

| 2014 |

|

| 10 December |

Onaga Takeshi assumes office as Governor of Okinawa. |

| 2015 |

|

| 16 July |

Okinawan “Third Party [Experts] Committee advises Oura Bay reclamation license issued December 2013 by (former) Governor Nakaima “flawed.” |

| 13 October |

Governor Onaga cancels Oura Bay reclamation license. |

| 27 October |

Government (Ishii, MLITT Minister) “suspends” Onaga order. |

| 2 November |

Okinawa prefecture complains to Disputes Council (Central and Local Government Disputes Management Council). |

| 17 November |

National Government (Ishii, MLITT) launches malfeasance suit under Administrative Appeals Act in Naha Court (Fukuoka High Court, Naha branch) against Okinawa seeking “proxy execution.” |

| 24 December |

Disputes Council refuses to act on prefectural complaint. |

| 25 December |

Prefecture launches suit in Naha court against government. |

| 2016 |

|

| 29 January |

Naha Court advises government and prefecture to settle. |

| 4 March |

Wakai (out-of-court) Settlement. |

| 7 March |

State (Ishii, MLITT) demands Onaga retract his cancelation order. |

| 14 March |

Onaga (Prefecture) refuses MLITT request (as an “illegal intervention by the state”). |

| 17 June |

Disputes Council refuses to rule, urging “sincere discussions” to resolve “continuing undesirable” relations between state and prefecture. |

| 22 July |

State launches new suit against prefecture in Naha Court. |

| 16 September |

Naha court verdict expected (likely to be followed by appeal to Supreme Court). |

Judicial Proceedings (3) “Out of Court”

However, no sooner had the “Amicable Settlement” with Okinawa promising those “discussions aimed at satisfactory resolution” been reached than Prime Minister Abe insisted anew that Henoko was “the only option,” implying that there was nothing to negotiate but Okinawa’s surrender.41 Just three days after agreeing to engage in discussions, and without so much as a preliminary meeting, MLITT Minister Ishii (for the government) sent Governor Onaga a formal request that he retract his cancellation of the Oura Bay reclamation license (i.e. that he restore the license granted by Nakaima in December 2013). It was exactly as prescribed under Paragraph 3 of the agreement, committing the parties to proceed in accord with Article 245 of the Local Autonomy Law, but it was plainly at odds with the prescription under Paragraph 8: that they negotiate.

“Until such time as a finalized court judgement on the proceedings for cancellation of the rectification order is issued, the plaintiff and other interested parties and the defendant will undertake discussions aimed at ‘satisfactory resolution’ (enman kaiketsu) of the Futenma airfield return and the current [Henoko] reclamation matter.”

On March 14, Governor Onaga responded, refusing. He pointed out that the Government had given no reason for its request and therefore his cancellation order could not be seen as a breach of the law.42 Submitting the matter to the Disputes Management Council, he referred to Ishii’s act as “an illegal intervention by the state.”43 It was, he said, a “pity” that the government had seen fit to issue such a Rectification Order immediately after entering the Amicable Agreement.

The five-member Disputes Management Council, since its establishment in 2000 had only twice been called upon to adjudicate a dispute and on neither occasion – both matters of relatively minor importance – had it issued any ruling against the government.44 It was an unlikely avenue for resolution of a major dispute between national and regional governments especially since it had abstained from doing so just months earlier, in December 2015, without so much as a statement of its reasons.

While the national government insisted there was no alternative to Henoko construction, Onaga told the Dispute Resolution Council that the project was “a monumental idiocy likely to cause a treasure of humanity to vanish from the earth.”45 There was little or no room for compromise between the prefecture’s argument that the Nakaima consent to reclamation was wrongful because it failed to meet the requirements of the Reclamation Act and the state’s argument that reclamation was within its powers because it had exclusive responsibility for defense and foreign relations.

The Council, however, on June 17, 2016 delivered an astonishing judgement: unanimously, it refused to rule on the legitimacy of MLITT Minster Ishii’s March order to the Okinawan Governor. The panel head, Kobayakawa Mitsuo, told a press conference,

“We thought issuing either a positive or a negative judgement on the rectification order would not be beneficial in helping the state and local governments create desirable relations.”46

The panel lamented the “continuing undesirable” state of relations between state and prefecture, and urged “sincere discussions” to reach agreement.47 Since it issued no ruling, it meant that Governor Onaga’s cancelation order remained in place, and that site works could not be resumed. In that sense it might be seen as a victory for the prefecture. But the constitutional problem was left: if a Commission especially set up to decide on disputes between national and regional governments could not resolve them, who or what could?

Judicial Proceedings (4) Back to Judge Tamiya’s Court

With the door thus closed by the Disputes Management Council, on July 22, the national government filed a fresh suit with the Naha branch of the Fukuoka High Court (i.e. Judge Tamiya’s court), seeking a ruling that the Okinawan government comply with the MLITT minister’s order and amend (reverse) its revocation of permission for landfill work on Oura Bay. It declared that it had already submitted its detailed case on grounds of foreign affairs and defence policy in the previous hearings and would not repeat it. It made no reference to Judge Tamiya’s injunction that central and regional government bodies perform “their respective functions as independent administrative bodies in an equal, cooperative relationship.” Nor did it mention his call for resolution of their differences by negotiation. It thus turned its back on the conciliation process ordered by Tamiya’s court when in January it called for:

“all Japan, including Okinawa, to come to an agreement on a solution and to seek the cooperation of the United States. If they did this, it could become the occasion for positive cooperation on the part of the US too, including broad reform.”

And likewise on the Disputes Council’s call for “sincere negotiations.” Its position that there was no alternative to Henoko construction and therefore nothing to negotiate bordered on contempt of court, and presented a dilemma for Judge Tamiya. As the Asahi Shimbun noted in March, the Abe government’s actions

“suggest the arrogance that comes from regarding Okinawa as an inferior, despite the High Court’s statement that the central government and all local governments are ‘equals’.”48

As for Okinawa, through its Governor and its Prefectural Assembly, its parliament, and through repeated mass gatherings of its citizens, as well as through its panel of lawyers in the Naha court, it made clear that it accepts, indeed embraces, the principle of equality enunciated by Tamiya and that, as an equal, it rules out any new base construction on its territory. Governor Onaga insisted (5 August) that he had exercised his authority properly and that there was no reason why he should submit to a contrary, improper “rectification” directive from the state. At issue, he insisted, were “fundamentals of regional self-government and by extension fundamentals of democracy.”49

Tamiya, undoubtedly under pressure from the government, adopted an extraordinarily fast “speed trial” schedule. From issue of the writs on July 22 there were just two open days of hearings (5 and 19 August), with verdict to be announced on 16 September. Tamiya dismissed the prefecture’s request to call eight expert witnesses (including Mayor Inamine of Nago City), and gave Onaga himself short shrift, again repeatedly asking him to confirm that he would obey the ruling of the court (a highly irregular query from the bench, according to lawyers present).50

Tamiya will rule on these vexing matters on 16 September. Whichever side “loses” at that stage is certain to appeal to the Supreme Court. Even then, however far from necessarily signifying an end to the problem that presumed “final” and “irreversible” judgement might simply spark a more intense level of political and social crisis, affecting in turn the Japan-US relationship and the frame of regional order. One of Okinawa’s most respected figures, the prize-winning novelist Medoruma Shun, who as a Henoko canoeist has formed part of the non-violent civic blockade designed to block reclamation works, commented,51

“It seems very unlikely that the Henoko new base construction problem can be solved solely by the administration, the law, or the parliament. Public opposition will keep delaying the construction. And the Japanese government will probably only give up on construction if public protest extends beyond Camp Schwab to US bases throughout the prefecture, and comes to affect the functioning of Kadena Air Base …”

That, Medoruma adds, is a far from impossible prospect.

Judicial precedents are not encouraging for Okinawa. In December 1959, the Supreme Court held in the “Sunagawa case” that matters pertaining to the security treaty with the US are “highly political” and concern Japan’s very existence, so that the judiciary should not pass judgement on them. That ruling, on expansion of the existing US base at Tachikawa (outside Tokyo), in effect elevated the Security Treaty above the constitution and immunized it from any challenge at law, thus entrenching the US base presence. It would be surprising if the 2016 (or 2017) court, addressing the project to create a new base at Henoko, did not follow this precedent.

Furthermore, it is just 20 years since then Okinawan Governor Ota Masahide (Governor 1990-1998) was arraigned before the Supreme Court facing the demand by the Prime Minister that he exercise his duties of state under the Local Self-Government Law to sign the proxy lease agreements on privately owned land appropriated by the US military (which he had refused to do). Ota made an eloquent plea, but the court dismissed it, contemptuously, in a two-sentence judgement.52 For Ota, the Supreme Court ruling was the last word. He submitted and signed the proxy lease agreements.

In the case of civil suits too, by Okinawan citizens and civic groups against the government of Japan, the record points to similar judicial inclination to endorse the state, dismissing the Okinawan case against it. One long-running (2009-2014) suit brought by a citizen group to have the environmental impact study on Henoko reopened because of its being fundamentally unscientific was dismissed at both initial hearing and later on appeal, the latter judgement so brief that it took just 30 seconds to read out. Other long-running suits have been pursued against the government over the intolerable levels of noise and nuisance emanating from the US bases. Between 2002 and 2015, courts have issued altogether seven judgements on this matter, repeatedly accepting evidence (in the words of the most recent judgement of Naha District Court in June 2015) that the 2200 plaintiffs of Ginowan City did indeed suffer “mental distress, poor sleep, and disruption to their daily lives” from “serous and widespread” violations that “could not be defended on any ground of public interest” and that they should therefore be paid 754 million yen (approximately $9 million) compensation. Courts have, however, refused to order a stop to that nuisance. By so doing, in effect they concede that the US military is beyond and above the law, and that the government of Japan is complicit in enforcing its ongoing illegality and the accompanying suffering of its people. As Ryukyu shimpo commented, “how could a government that enforces continuing illegality upon the citizens of one of its regions be considered a law-ruled state?”53

Confrontation

While court battles engage a small army of lawyers and officials, it is the citizen engagement on the front lines, at Henoko and Takae, that best embodies the Okinawan spirit. Despite being relatively remote and difficult of access from major population centers, especially in the early mornings, Henoko has become one of the longest sit-in protests of modern times, sustaining a ten-year protest encampment at the fishing harbour which saw off the first design for a floating heliport base in 2005 and then continued till July 2015, when it was joined by the encampment at the gate to Camp Schwab marine base, a couple of kilometres from the fishing harbour. From July 2014, this Schwab-gate site became the main access route to the construction site. Core protesters are often supplemented by “All Okinawa” chartered buses bringing volunteers from throughout the island. On an average day, the core group may be between sixty and one hundred or so protesters, but on special occasions many more, as on the 500th day of the Camp Schwab Gate camp, 18 November 2015, that attracted over 1,000. The impromptu exchange of experience and ideas, interspersed with performances of song or dance, grew during 2016 to such extent that the gathering declared itself “Henoko University” and organized a series of “lectures” by activists and scholars.

While the citizenry remained resolutely non-violent and exercised the right of civil disobedience only after exhausting all legal and constitutional steps to oppose the base project, the National Coastguard and Riot Police flaunted their violence, dragging away protesters (quite a few of whom are in their 70s and 80s), dunking canoeists in the sea, pinning down one protest ship captain till he lost consciousness, and on a number of occasions causing injuries to protesters requiring hospital treatment.54 On 20 November 2014, 85 year old Shimabukuro Fumiko (a Battle of Okinawa survivor) was carried off to hospital from the Camp Schwab protest gathering suffering a suspected concussion. On the following day journalists from the Okinawan daily Ryukyu shimpo were manhandled, abused and forcibly removed from the site. On 20 January 2015, a Coastguard officer gripped a woman film maker around the neck with his legs (a “horse riding” assault) intent on wrenching away her camera. Protesting canoeists and kayakers were intimidated and driven off or on occasion dumped at sea, as far as four kilometres from shore, after being held for varying periods.

On 22 February 2016, just before the opening of a mass protest meeting at the gate of Camp Schwab, local Japanese security agents for the US Marine Corps arrested three protesters, including the head of the Okinawa Peace Movement Centre, Yamashiro Hiroji, on suspicion of breaching the special criminal law (adopted in 1952 at the height of the Korean War to prescribe stringent punishment for unauthorized entry or attempted entry into US bases in Japan). Film footage showed Yamashiro, ordering demonstrators to be especially careful not to cross the boundary line, being suddenly attacked, flung to the ground, handcuffed, and dragged feet-first into the base by US Marine Corps security personnel. As the Okinawa Times noted, it appeared to be a clear case in which the constitutional right to freedom of assembly, opinion, and expression had been sacrificed to the overarching extraterritorial rights enjoyed by the US.55 For Okinawans, it suggested a return to the lawless 1950s when US forces confiscated land and constructed bases at will (under “bayonet and bulldozer”), and treated Okinawans with violence and contempt. Two months later, on 1 April 2016, the prize-winning novelist, Medoruma Shun, was pulled from his kayak and held, first by US and then by Japanese authorities, for a total of 34 hours under the stringent Special Criminal Law – as if he were planning to attack the base.56

As these matters were prominently reported in the Okinawan (but barely mentioned in the mainland) media, Abe’s close friend and his appointee (in 2013) to the board of governors of Japan’s public broadcasting corporation, NHK, the novelist Hyakuta Naoki, expressed the view that the two Okinawan newspapers (Ryukyu shimpo and Okinawa Times) should be closed down because they express “traitorous” views.57

Even as the confrontation continued and deepened at the Henoko site, the government strove to “buy off” opposition where it could. Since Nago City had from 2010 twice returned a mayor and local assembly majority that resisted all attempts at suasion and refused to accept any monies linked to it, Abe, Shimajiri, and other members of government worked to find ways to divide and weaken the city’s anti-base movement. Late in October, the heads of three of the city’s 55 sub-districts (ku) – Henoko, Kushi and Toyohara (population respectively 2014, 621, and 427) – were invited to the Prime Minister’s office in Tokyo. They set out their wish list, asking for repairs to the local community halls, purchase of lawnmowers, and provision of one (or perhaps several) “azumaya” (a kind of summer-house or gazebo).58 They were told they were to be allocated the sum of 13 million yen each in the 2016 budget, a subsidy that would bypass the representative institutions of the city and prefecture. It was to be (as Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga later put it), “compensation” for the noise and nuisance caused them by the protest movement.

Suga declared that the local ku districts “agreed” to the Henoko construction albeit with some strings attached, and suggested it was only natural that they be given every encouragement. However, within weeks, all three heads contradicted him, saying he had misunderstood them. The head of Kushi insisted that the district had not changed its opposition to Henoko base construction since taking that position in 1997, and the head of Toyohara stated that “absolutely no-one in Toyohara” wanted a base.59

It was a trifling enough sum (less than half a million dollars in all), but the appropriation of public funds, with no accountability, to encourage a cooperative, base-tolerant spirit in a few corners of a stubbornly anti-base city was, as Ryukyu shimpo put it, an “unprecedented politics of division.”60 It was also an almost certainly illegal attempt to evade democratic will and constitutional procedure.61

Elections, 2016

In 2016, while the contest continued and intensified at Camp Schwab gate and in the courts, three important elections were held: in January for mayor of Ginowan City, in June for the Okinawan Prefectural Assembly, and in July for the upper house (House of Councillors) in the national diet. In the second and third of these, Tokyo-supported candidates were soundly defeated, an “All Okinawa” majority supporting the Governor was confirmed in the prefectural assembly, and in the Upper House of the Diet one of the best-known opponents of base substitution within Okinawa, Iha Yoichi, (Ginowan mayor for two terms, 2003-2010) was chosen by a huge majority over the Abe government’s favourite (and from late 2015 actually Minister for Okinawa), Shimajiri Aiko. The margin of defeat, 100,000 votes, signified her humiliation. Both of these may be considered “All Okinawa” victories.

In Ginowan City the outcome was more nuanced.62 The Abe government’s anointed candidate, the incumbent Sakima Atsushi, had been elected to the office in 2012 on a “no new base for Okinawa” pledge but, like Shimajiri, was party to a collective Okinawan “tenko” (conversion under pressure) the following year, abandoning his campaign political pledge and switching to favour construction of the “Futenma replacement facility” at Henoko. In the January 2016 election, he defeated the “All Okinawa” candidate, Shimura Keiichiro, by a comfortable margin, 27,668 to 21,811. Prime Minister Abe declared himself “greatly encouraged” and said he would “continue efforts at dialogue in order to lessen the burden on Okinawa and promote its development.”63 But the outcome can scarcely be seen as an Abe victory since both candidates promised to secure reversion of Futenma, Sakima within three years (by 2019) and Shimura within five years (by 2021). The victorious Sakima did not so much as mention the word “Henoko” during his campaign (the only difference in their speeches was Shimura’s phrase “without allowing any new base to be built”) and both he and his Abe government supporters must have known full well that there would be no Futenma return within either three or five years. Sakima made one other campaign promise, to attract a “Disneyland” to the City, but it was equally unrealistic, and was dismissed as pipedream by Disneyland (Oriental Land Company) executives shortly after the election. There would be no Futenma return within three (or five) years and no Ginowan City Disneyland ever.

Apart from consistently returning anti-base candidates, Okinawa showed itself unforgiving of candidates who, once elected on an anti-Henoko base construction platform, then reversed themselves. Most notable in this category is Nakaima Hirokazu (Governor 2006-2014), (re-) elected in 2010 on an anti-base platform who famously “turned coat” during a week secreted in a Tokyo hospital in December 2013. In the subsequent November 2014 gubernatorial election he was resoundingly dismissed by the electorate. Likewise, Upper House member Shimajiri Aiko, elected in 2010 on an anti-base platform who “turned coat” in April 2013 and later that same year led the “surrender” of conservative Diet members. She was highly appreciated in Abe circles not only for her role in orchestrating the crucial 2013 reversal but for the views she expressed later: calling for the Riot Police and Coastguard to be mobilized to curb the “illegal, obstructionist activities” of the anti-base movement (February 2014), denouncing Nago mayor Inamine for “abusing his power (April 2015), and referring contemptuously to the “irresponsible citizens’ movement” (October 2015). With such views, she rose meteorically in the Tokyo establishment, becoming Minister for Okinawa in the third Abe cabinet (with responsibilities that included also the Northern Territories, science and technology, space, oceans, territorial problems, IT, and “cool Japan”). But to rise in Tokyo is to fall in Okinawa, and in July 2016 Okinawans dismissed her by a massive 100,000 vote margin.64

Futenma – Reversion?

Already twenty years have passed since 1996 when Tokyo and Washington first promised Futenma return “within 5 to 7 years,” i.e., by 2003. In December 2013, Prime Minister Abe promised Governor Nakaima to accomplish it by February 2019, but when Abe conveyed this request to Washington in February 2014, Marine Commander Wissler explicitly ruled it out.65 In the Ginowan City mayoral election of January 2016 the Abe-supported conservative candidate gave that same date as his pledge to the city. Already by then, however, at the inter-governmental (US-Japan) level the date for completion and handover of the new facility had been set as “no earlier than 2022.”66 In 2016, as the 20th anniversary of the original agreement passed, the Marine Corps’ “Marine Aviation Plan 2016″ pushed it further back to fiscal year 2025 (October 2024-September 2025).67 Admiral Harry Harris, Commander-of US Pacific forces, gave that date in evidence to Congress early in 2016.68 Harris noted that, of 200 base transfer-related items carried in Japan’s 2015 budget, just nine had been completed, eight were still underway, and the situation at the Henoko site was not improving but rather protest was “continuing to escalate.”69

But even as that date was being reluctantly accepted by the Marine Corps and Congress, at the beginning of March 2016, Japan despatched its top security official, Yachi Shotaro, to Washington to seek the Obama government’s understanding for a further substantial delay.70 Only after the US consented did the Abe government come to an “out-of-court” March 4 agreement (with Okinawa Prefecture) that involved a complete and indefinite suspension of site works at Henoko. Lt. General Robert Neller, commander of the US Marine Corps, told a Senate military affairs committee meeting that the wakai suspension could be expected to last a further 12-months.71 President Obama, advised of the impending delay, is said to have responded with “So there will be nothing happening for a while then.”72

It means that the Government of Japan has promised the Government of the United States that Henoko works will resume around February 2017, for a base that will be completed and handed over to the Marine Corps around 2026. Even for that to happen, somehow in the remaining months it must extract the legal warrant to resume works at Henoko. Given the well-demonstrated ability of the protest movement to delay and obstruct construction of the new base, even 2026 could prove a conservative estimate.

Takae – Reversion?

Takae deserves a special place in any consideration of the Okinawa struggle. Like Henoko, its travails date to 1996. Under the agreement of that year, as condition for the return of about half of the Marine Corps’ Camp Gonsalves’ Jungle Warfare Center in the Yambaru forest, six “Helicopter Landing Pads” were to be constructed. Only after completion of the environmental impact study (2007-2012) did the government reveal that they would be used, not by the conventional CH 46 helicopter but the ear-crushingly noisy and dangerous vertical takeoff and landing “Osprey.” When the residents of Takae village (population ca 150) began a roadside protest in 2007, the government resorted to various devices, including “SLAPP”-type restraining court orders against it.73 In February 2015 Japan handed over to the Marine Corps in advance two completed Osprey pads. As it did so, the Higashi Village Assembly adopted unanimously a resolution declaring that the Osprey-pad construction contravened the wishes of the local community and banning US aircraft from using them. Days later, on 25 February 2015, the Marine Corps’ Osprey appeared at the site and began training flights. From the start, it was flying roughly twice as often as the CH-46 it replaced. 74 By June 2016, the Okinawa Defense Bureau reported that the especially aggravating night flights had increased 8-fold over 2014, to 400 that month.75 These were especially terrifying when conducted without lights. When the Noguchigera woodpecker began to die mysteriously, some suspected that the avian nervous system too could not cope with the disturbance to their world brought by the Osprey.76 But the US military enjoyed priority over all the forest dwellers, not only human but animal, avian, insect or botanical.

The once peaceful, bio-diverse, forested environment became a virtual war zone. A local newspaper conducted a door-to-door survey of opinion among local residents and found opposition running at 80 per cent, with not one soul in favour.77

On 22 July 2016, weeks after the Upper House election in which the Abe government’s key Okinawa policy person, Shimajiri Aiko, was humiliated, the government launched a full-scale assault on Takae (following prolonged suspension of operations partly to avoid disturbing forest birds during breeding time and partly to avoid political damage in the forthcoming Upper House election), mobilizing a small army of over 500 riot police from various parts of mainland Japan to lay siege to the 150-person population of Takae, creating in effect a “law-less” zone.78 This Abe “army” aimed to crush the Okinawan resistance at a point where it was most difficult to mount, sweeping aside the Takae protest tents and vehicles and periodically closing or limiting traffic on Highway 70.79 As Ryukyu shimpo pointed out, it was the sort of mobilization of force with which a major assault on a yakuza gangster headquarters might be launched.80 For the people carrying on the resistance year after year, mostly small farmers, the experience of being overwhelmed by state force, outnumbered roughly 5:1, was “akin to martial law” as novelist Medoruma put it.81 Late in August 2016, the 87 year-old Shimabukuro Fumiko, front-line heroine of the Okinawan resistance, was carried off to hospital for a second time after falling in the melee at Takae.

For the first time, the prefectural parliament, the Prefectural Assembly, adopted a resolution calling for immediate halt to the works.82 The American veterans’ organization, the 3,000-strong Veterans for Peace, issued a statement from its Berkeley California annual meeting denouncing the action to crush demonstrators at Takae.

“Whereas, on July 22, reportedly as many as 800 riot police, collected from all over Japan, swarmed into the tiny village of Takae (which is surrounded by a sub-tropical forest that could qualify as a world heritage site), tore down their tents and towed away their cars, reaffirming that the Government views Okinawa as a colony …”

and urging the US government to distance itself from such repressive, shameful acts.83

Frontier Islands

The problem of Okinawa’s Frontier or Southwest (Sakishima or Nansei) islands has to be understood in the same frame as the “Okinawa problem” and the “Henoko problem.” As noted above, these islands were assigned to China in the draft Sino-Japanese treaty of 1880, only remaining in Japan’s hands because China had second thoughts. Throughout the Cold War, the 600 kilometre chain of Southwest Japanese islands stretching through the East China Sea from Naha to Taiwan remained peaceful and stable, with no significant military presence despite the Cold War. Yonaguni was as much “offshore” from Taiwan and China in the East China Sea as from Japan, and it relied on two policemen, a hand-gun apiece, to keep order.84

From the time of the Democratic Party governments of 2009-2012 the commitment to establish a military presence on these islands has been part of a bipartisan security consensus, especially following the 2010 incidents at sea between Japan and China over the Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands (for administrative purposes part of the Okinawan Yaeyama Island group). As in Henoko and Takae, for these islands too national policy exigency overrides all other considerations.

In the midst of a booming region, Yonaguni suffers population attrition and economic decline because of the lack of direct transport or communications links with either Taiwan or China. Populated half a century ago by over 10,000 people but now a mere 1,500, uniquely in Japan it has twice in the past decade formally debated its collective future, in 2004-5 and in 2008-2015. In 2005, it formulated a “Vision” for a future based on regional (East China Sea) cooperation and open door trade, fishing and tourism link with Taiwan, but Tokyo forbade it. Then, following a US naval intelligence-gathering visit to the island in 2007, a different, even opposite, idea of a military centred future began to gather attention. A petition to urge a base presence was organized in 2008 by a local “Defense Association.” In June 2009, the Yonaguni mayor, Hokama Shukichi, approached the Ministry of Defense and the Ground Self-Defense Forces to suggest they set up a base on the island. There followed a series of elections, referenda, and bitterly divisive campaigns contested by pro- and anti-base forces. The matter was eventually resolved by the narrow election victory of the pro-base mayor in June 2013 (553:506) followed by a “Yes” to the SDF in an island referendum in February 2015 (632:445). Early in 2016, the base was ready and the Ground Self Defense Force (GSDF) unit marched in.

Fatigue from years of bitter struggle in the small, close-knit island community played a large role in the outcome. Many were discouraged by the silence of Governor Onaga. They had assumed, following his victory in November 2014 that he would incorporate the island within his general “All Okinawa” anti-base camp. Without external support, and knowing that Minister of Defense Nakatani Gen had said that construction was going to proceed irrespective of the 2015 poll result, it seemed futile for a few hundred islanders to attempt to resist the determined central government. Still, 41 per cent of islanders did return a “No” vote, showing that divisions in the community remained deep. As the GSDF began its surveillance of Chinese shipping and other communications, islanders could be sure that they had at least earned a place on the Chinese missile target list. Those who remember the consequences of an Okinawan role in defence of “mainland” Japan in 1945 contemplate the new arrangements with deep misgivings.

Some in the other Japanese SDF services (Air and Maritime) suspected that “turf” considerations were a major factor behind the GSDF deployment to Yonaguni (and other frontier islands), compensating for the loss of role in Hokkaido where, through the Cold War, they prepared for a putative land attack by Soviet forces. In the post-Cold War, post-War on Terror era, the South-West was the growth area for Japan’s military. Apart from Yonaguni, Miyako was targeted for an 800-strong security and missile force, with another 500 likely to be sent to Amami Oshima in Kagoshima prefecture.85 500-more had been ear-marked for Ishigaki Island, where the conservative mayor is known to be supportive and Maritime SDF ships welcomed.86

Outlook

Okinawan people’s faith in justice and democracy has been sorely tested ever since its “reversion” to Japan under a secret deal over 40 years ago in which Okinawan opinion was ignored and the prosecution of the US war in Southeast Asia prioritized. However many times and in however many different forums Okinawans insist that no new base be allowed, it makes no difference. Construction of the Henoko base and the “Osprey pads” designed to accommodate them, is a core national policy, and the key raison d’êtrefor Okinawa in the eyes of Tokyo is as a joint US-Japan bastion projecting force where required for the regional and global hegemonic project.

The role of “base island” long imposed on the Okinawan people by the US and Japanese governments has meant for them not just deprivation of sovereignty and territory but deprivation of personal security in the name of national security. As the current phase of Okinawan protest had been triggered by the rape case of 1995, so it was again in May 2016. Sadness and anger stirred the anti-base movement again over the rape and murder of a 20-year old Okinawan woman, to which an American ex-Marine base worker confessed.87 Indelibly etched on the Okinawan collective memory are not just the 1995 case but many others going back to the rape-murder of 6 year-old Yumiko-chan in 1955 and the crash of a fighter jet onto Miyamori Primary School in 1959 (killing 17 people, including 11 children). A protest and mourning meeting attended by some 400 citizens at short notice on 25 May adopted five demands: drastic overall reduction of US bases, basic revision of the US-Japan SOFA (Status of Forces Agreement), closure and return of Futenma, withdrawal of Osprey, and abandonment of Henoko. Two days later the Prefectural Assembly adopted almost identical demands, but adding that all Marine Corps bases and soldiers (i.e., not just Futenma but also the large, sprawling bases at Camp Schwab, Camp Hansen, and the Northern Training Area) withdraw from the island.88

Then, a prefectural mass meeting on 19 June, in sombre, mourning mood under a blazing 35 degree sun, heard a message from the father of the victim asking for prefectural unity in demanding withdrawal of all bases. A coalition of 16 Okinawan women’s organizations making up the “Okinawa Women Act against Military Violence” announced the same demand, for the withdrawal of all military bases and armed forces (thereby including also the massive US Air Force base at Kadena and Japan’s own Self-Defense Force units).89 As posters held by many of the 65,000 who gathered to mourn the victim at the prefectural mass meeting on June 19 declared, the people’s anger “has gone beyond any limit.”

Over the 43 years since Okinawa was resumed within Japan in 1972, by official count US forces and their dependents and civil employees had been responsible for 5,896 criminal incidents, one tenth of them (574) crimes of violence including rape.90 Countless resolutions of protest had been met with countless promises of good behavior. The Okinawan mood was such that the same promises of future “good behavior” no longer sufficed. A gulf began to open between those calling for withdrawal of all Marines or even all military forces from the island and the “All Okinawa” leadership, including Governor Onaga, who stuck resolutely to the more limited (if nevertheless major) demands: Close Futenma without substitution (no Henoko), and withdraw Osprey.

The crisis today pits the “irresistible force” of the nation state against the “immovable object” of the Okinawan resistance in a grand, and massively unequal, struggle. At sea, a miniscule flotilla of canoes and kayaks confronts a solid wall of National Coastguard ships and on land a few hundred protesters face off 24 hours a day against riot police outside Camp Schwab Marine Corps base and Takae, trying to block reclamation and construction works on Oura Bay and in the Yambaru forest.