This article by award winning author Professor David Ray Griffin was first published on September 10, 2008. We are reposting this article in the context of the 15 years commemoration of the 9/11. This carefully researched article is of particular relevance in relation to the rising tide of Islamophobia in Europe and North America

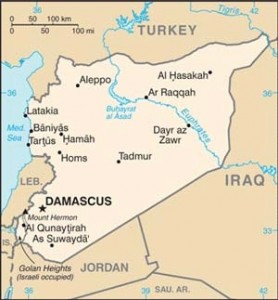

Much of America’s foreign policy since 9/11 has been based on the assumption that it was attacked by Muslims on that day. This assumption was used, most prominently, to justify the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is now widely agreed that the use of 9/11 as a basis for attacking Iraq was illegitimate: none of the hijackers were Iraqis, there was no working relation between Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden, and Iraq was not behind the anthrax attacks. But it is still widely believed that the US attack on Afghanistan was justified. For example, the New York Times, while referring to the US attack on Iraq as a “war of choice,” calls the battle in Afghanistan a “war of necessity.” Time magazine has dubbed it “the right war.” And Barack Obama says that one reason to wind down our involvement in Iraq is to have the troops and resources to “go after the people in Afghanistan who actually attacked us on 9/11.”

The assumption that America was attacked by Muslims on 9/11 also lies behind the widespread perception of Islam as an inherently violent religion and therefore of Muslims as guilty until proven innocent. This perception surely contributed to attempts to portray Obama as a Muslim, which was lampooned by a controversial cartoon on the July 21, 2008, cover of The New Yorker.

As could be illustrated by reference to many other post-9/11 developments, including as spying, torture, extraordinary rendition, military tribunals, America’s new doctrine of preemptive war, and its enormous increase in military spending, the assumption that the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were attacked by Muslim hijackers has had enormous negative consequences for both international and domestic issues.1

Is it conceivable that this assumption might be false? Insofar as Americans and Canadians would say “No,” they would express their belief that this assumption is not merely an “assumption” but is instead based on strong evidence. When actually examined, however, the proffered evidence turns out to be remarkably weak. I will illustrate this point by means of 16 questions.

1. Were Mohamed Atta and the Other Hijackers Devout Muslims?

The picture of the hijackers conveyed by the 9/11 Commission is that they were devout Muslims. Mohamed Atta, considered the ringleader, was said to have become very religious, even “fanatically so.”2 Being devout Muslims, they could be portrayed as ready to meet their Maker—as a “cadre of trained operatives willing to die.”3

But this portrayal is contradicted by various newspaper stories. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Atta and other hijackers had made “at least six trips” to Las Vegas, where they had “engaged in some decidedly un-Islamic sampling of prohibited pleasures.” These activities were “un-Islamic” because, as the head of the Islamic Foundation of Nevada pointed out: “True Muslims don’t drink, don’t gamble, don’t go to strip clubs.”4

One might, to be sure, rationalize this behavior by supposing that these were momentary lapses and that, as 9/11 approached, these young Muslims had repented and prepared for heaven. But in the days just before 9/11, Atta and others were reported to be drinking heavily, cavorting with lap dancers, and bringing call girls to their rooms. Temple University Professor Mahmoud Ayoub said: “It is incomprehensible that a person could drink and go to a strip bar one night, then kill themselves the next day in the name of Islam. . . . Something here does not add up.”5

In spite of the fact that these activities were reported by mainstream newspapers and even the Wall Street Journal editorial page,6 the 9/11 Commission wrote as if these reports did not exist, saying: “we have seen no credible evidence explaining why, on [some occasions], the operatives flew to or met in Las Vegas.”7

2. Do Authorities Have Hard Evidence of Osama bin Laden’s Responsibility for 9/11?

Whatever be the truth about the devoutness of the hijackers, one might reply, there is certainly no doubt about the fact that they were acting under the guidance of Osama bin Laden. The attack on Afghanistan was based on the claim that bin Laden was behind the attacks, and the 9/11 Commission’s report was written as if there were no question about this claim. But neither the Bush administration nor the Commission provided any proof for it.

Two weeks after 9/11, Secretary of State Colin Powell, speaking to Tim Russert on “Meet the Press,” said he expected “in the near future . . . to put out . . . a document that will describe quite clearly the evidence that we have linking [bin Laden] to this attack.”8 But at a press conference with President Bush the next morning, Powell reversed himself, saying that although the government had information that left no question of bin Laden’s responsibility, “most of it is classified.”9 According to Seymour Hersh, citing officials from both the CIA and the Department of Justice, the real reason for the reversal was a “lack of solid information.”10

That same week, Bush had demanded that the Taliban turn over bin Laden. But the Taliban, reported CNN, “refus[ed] to hand over bin Laden without proof or evidence that he was involved in last week’s attacks on the United States.” The Bush administration, saying “[t]here is already an indictment of Osama bin Laden” [for the attacks in Tanzania, Kenya, and elsewhere],” rejected the demand for evidence with regard to 9/11.11

The task of providing such evidence was taken up by British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who on October 4 made public a document entitled “Responsibility for the Terrorist Atrocities in the United States.” Listing “clear conclusions reached by the government,” it stated: “Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda, the terrorist network which he heads, planned and carried out the atrocities on 11 September 2001.”12

Blair’s report, however, began by saying: “This document does not purport to provide a prosecutable case against Osama Bin Laden in a court of law.” This weakness was noted the next day by the BBC, which said: “There is no direct evidence in the public domain linking Osama Bin Laden to the 11 September attacks. At best the evidence is circumstantial.”13

After the US had attacked Afghanistan, a senior Taliban official said: “We have asked for proof of Osama’s involvement, but they have refused. Why?”14 The answer to this question may be suggested by the fact that, to this day, the FBI’s “Most Wanted Terrorist” webpage on bin Laden, while listing him as wanted for bombings in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Nairobi, makes no mention of 9/11.15

When the FBI’s chief of investigative publicity was asked why not, he replied: “The reason why 9/11 is not mentioned on Usama Bin Laden’s Most Wanted page is because the FBI has no hard evidence connecting Bin Laden to 9/11.”16

It is often claimed that bin Laden’s guilt is proved by a video, reportedly found by US intelligence officers in Afghanistan in November 2001, in which bin Laden appears to report having planned the attacks. But critics, pointing out various problems with this “confession video,” have called it a fake.17 General Hamid Gul, a former head of Pakistan’s ISI, said: “I think there is an Osama Bin Laden look-alike.”18 Actually, the man in the video is not even much of a look-alike, being heavier and darker than bin Laden, having a broader nose, wearing jewelry, and writing with his right hand.19 The FBI, in any case, obviously does not consider this video hard evidence of bin Laden’s responsibility for 9/11.

What about the 9/11 Commission? I mentioned earlier that it gave the impression of having had solid evidence of bin Laden’s guilt. But Thomas Kean and Lee Hamilton, the Commission’s co-chairs, undermined this impression in their follow-up book subtitled “the inside story of the 9/11 Commission.”20

Whenever the Commission had cited evidence for bin Ladin’s responsibility, the note in the back of the book always referred to CIA-provided information that had (presumably) been elicited during interrogations of al-Qaeda operatives. By far the most important of these operatives was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), described as the “mastermind” of the 9/11 attacks. The Commission, for example, wrote:

Bin Ladin . . . finally decided to give the green light for the 9/11 operation sometime in late 1998 or early 1999. . . . Bin Ladin also soon selected four individuals to serve as suicide operatives. . . . Atta—whom Bin Ladin chose to lead the group—met with Bin Ladin several times to receive additional instructions, including a preliminary list of approved targets: the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the U.S. Capitol.21

The note for each of these statements says “interrogation of KSM.”22

Kean and Hamilton, however, reported that they had no success in “obtaining access to star witnesses in custody . . . , most notably Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.”23 Besides not being allowed to interview these witnesses, they were not permitted to observe the interrogations through one-way glass or even to talk to the interrogators.24 Therefore, they complained: “We . . . had no way of evaluating the credibility of detainee information. How could we tell if someone such as Khalid Sheikh Mohammed . . . was telling us the truth?”25

An NBC “deep background” report in 2008 pointed out an additional problem: KSM and the other al-Qaeda leaders had been subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques,” i.e., torture, and it is now widely acknowledged that statements elicited by torture lack credibility. “At least four of the operatives whose interrogation figured in the 9/11 Commission Report,” this NBC report pointed out, “have claimed that they told interrogators critical information as a way to stop being “-tortured.'” NBC then quoted Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, as saying: “Most people look at the 9/11 Commission Report as a trusted historical document. If their conclusions were supported by information gained from torture, . . . their conclusions are suspect.”26

Accordingly, neither the White House, the British government, the FBI, nor the 9/11 Commission has provided solid evidence that Osama bin Laden was behind 9/11.

3. Was Evidence of Muslim Hijackers Provided by Phone Calls from the Airliners?

Nevertheless, many readers may respond, there can be no doubt that the airplanes were taken over by al-Qaeda hijackers, because their presence and actions on the planes were reported on phone calls by passengers and flight attendants, with cell phone calls playing an especially prominent role.

The most famous of the reported calls were from CNN commentator Barbara Olson to her husband, US Solicitor General Ted Olson. According to CNN, he reported that his wife had “called him twice on a cell phone from American Airlines Flight 77,” saying that “all passengers and flight personnel, including the pilots, were herded to the back of the plane by . . . hijackers [armed with] knives and cardboard cutters.”27

Although these reported calls, as summarized by Ted Olson, did not describe the hijackers so as to suggest that they were members of al-Qaeda, such descriptions were supplied by calls from other flights, especially United 93, from which about a dozen cell phone calls were reportedly received before it crashed in Pennsylvania. According to a Washington Post story of September 13,

[P]assenger Jeremy Glick used a cell phone to tell his wife, Lyzbeth, . . . that the Boeing 757’s cockpit had been taken over by three Middle Eastern-looking men. . . . The terrorists, wearing red headbands, had ordered the pilots, flight attendants and passengers to the rear of the plane.28

A story about a “cellular phone conversation” between flight attendant Sandra Bradshaw and her husband gave this report:

She said the plane had been taken over by three men with knives. She had gotten a close look at one of the hijackers. . . . “He had an Islamic look,” she told her husband. 29

From these calls, therefore, the public was informed that the hijackers looked Middle Eastern and even Islamic.

Still more specific information was reportedly conveyed during a 12-minute cell phone call from flight attendant Amy Sweeney on American Flight 11, which was to crash into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.30 After reaching American Airlines employee Michael Woodward and telling him that men of “Middle Eastern descent” had hijacked her flight, she then gave him their seat numbers, from which he was able to learn the identity of Mohamed Atta and two other hijackers.31 Amy Sweeney’s call was critical, ABC News explained, because without it “the plane might have crashed with no one certain the man in charge was tied to al Qaeda.”32

There was, however, a big problem with these reported calls: Given the technology available in 2001, cell phone calls from airliners at altitudes of more than a few thousand feet, especially calls lasting more than a few seconds, were not possible, and yet these calls, some of which reportedly lasted a minute or more, reportedly occurred when the planes were above 30,000 or even 40,000 feet. This problem was explained by some credible people, including scientist A.K. Dewdney, who for many years had written a column for Scientific American.33

Although some defenders of the official account, such as Popular Mechanics, have disputed the contention that high-altitude calls from airliners were impossible,34 the fact is that the FBI, after having at first supported the claims that such calls were made, withdrew this support a few years later.

With regard to the reported 12-minute call from Amy Sweeney to Michael Woodward, an affidavit signed by FBI agent James Lechner and dated September 12 (2001) stated that, according to Woodward, Sweeney had been “using a cellular telephone.”35 But when the 9/11 Commission discussed this call in its Report, which appeared in July 2004, it declared that Sweeney had used an onboard phone.36

Behind that change was an implausible claim made by the FBI earlier in 2004: Although Woodward had failed to mention this when FBI agent Lechner interviewed him on 9/11, he had repeated Sweeney’s call verbatim to a colleague in his office, who had in turn repeated it to another colleague at American headquarters in Dallas, who had recorded it; and this recording—which was discovered only in 2004—indicated that Sweeney had used a passenger-seat phone, thanks to “an AirFone card, given to her by another flight attendant.”37

This claim is implausible because, if this relayed recording had really been made on 9/11, we cannot believe that Woodward would have failed to mention it to FBI agent Lechner later that same day. While Lechner was taking notes, Woodward would surely have said: “You don’t need to rely on my memory. There is a recording of a word-for-word repetition of Sweeney’s statements down in Dallas.” It is also implausible that Woodward, having repeated Sweeney’s statement that she had used “an AirFone card, given to her by another flight attendant,” would have told Lechner, as the latter’s affidavit says, that Sweeney had been “using a cellular telephone.”

Lechner’s affidavit shows that the FBI at first supported the claim that Sweeney had made a 12-minute cell phone call from a high-altitude airliner. Does not the FBI’s change of story, after its first version had been shown to be technologically impossible, create the suspicion that the entire story was a fabrication?

This suspicion is reinforced by the FBI’s change of story in relation to United Flight 93. Although we were originally told that this flight had been the source of about a dozen cell phone calls, some of them when the plane was above 40,000 feet, the FBI gave a very different report at the 2006 trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, the so-called 20th hijacker. The FBI spokesman said: “13 of the terrified passengers and crew members made 35 air phone calls and two cell phone calls.”38 Instead of there having been about a dozen cell phone calls from Flight 93, the FBI declared in 2005, there were really only two.

Why were two calls still said to have been possible? They were reportedly made at 9:58, when the plane was reportedly down to 5,000 feet.39 Although that was still pretty high for successful cell phone calls in 2001, these calls, unlike calls from 30,000 feet or higher, would have been at least arguably possible.

If the truth of the FBI’s new account is assumed, how can one explain the fact that so many people had reported receiving cell phone calls? In most cases, it seems, these people had been told by the callers that they were using cell phones. For example, a Newsweek story about United 93 said: “Elizabeth Wainio, 27, was speaking to her stepmother in Maryland. Another passenger, she explains, had loaned her a cell phone and told her to call her family.”40 In such cases, we might assume that the people receiving the calls had simply mis-heard, or mis-remembered, what they had been told. But this would mean positing that about a dozen people had made the same mistake.

An even more serious difficulty is presented by the case of Deena Burnett, who said that she had received three to five calls from her husband, Tom Burnett. She knew he was using his cell phone, she reported to the FBI that very day and then to the press and in a book, because she had recognized his cell phone number on her phone’s Caller ID.41 We cannot suppose her to have been mistaken about this. We also, surely, cannot accuse her of lying.

Therefore, if we accept the FBI’s report, according to which Tom Burnett did not make any cell phone calls from Flight 93, we can only conclude that the calls were faked—that Deena Burnett was duped. Although this suggestion may at first sight seem outlandish, there are three facts that, taken together, show it to be more probable than any of the alternatives.

First, voice morphing technology was sufficiently advanced at that time to make faking the calls feasible. A 1999 Washington Post article described demonstrations in which the voices of two generals, Colin Powell and Carl Steiner, were heard saying things they had never said.42

Second, there are devices with which you can fake someone’s telephone number, so that it will show up on the recipient’s Caller ID.43

Third, the conclusion that the person who called Deena Burnett was not her husband is suggested by various features of the calls. For example, when Deena told the caller that “the kids” were asking to talk to him, he said: “Tell them I’ll talk to them later.” This was 20 minutes after Tom had purportedly realized that the hijackers were on a suicide mission, planning to “crash this plane into the ground,” and 10 minutes after he and other passengers had allegedly decided that as soon as they were “over a rural area” they must try to gain control of the plane. Also, the hijackers had reportedly already killed one person.44 Given all this, the real Tom Burnett would have known that he would likely die, one way or another, in the next few minutes. Is it believable that, rather than taking this probably last opportunity to speak to his children, he would say that he would “talk to them later”? Is it not more likely that “Tom” made this statement to avoid revealing that he knew nothing about “the kids,” perhaps not even their names?

Further evidence that the calls were faked is provided by timing problems in some of them. According to the 9/11 Commission, Flight 93 crashed at 10:03 as a result of the passenger revolt, which began at 9:57. However, according to Lyzbeth Glick’s account of the aforementioned cell phone call from her husband, Jeremy Glick, she told him about the collapse of the South Tower, and that did not occur until 9:59, two minutes after the alleged revolt had started. After that, she reported, their conversation continued for several more minutes before he told her that the passengers were taking a vote about whether to attack. According to Lyzbeth Glick’s account, therefore, the revolt was only beginning by 10:03, when the plane (according to the official account) was crashing.45

A timing problem also occurred in the aforementioned call from flight attendant Amy Sweeney. While she was describing the hijackers, according to the FBI’s account of her call, they stormed and took control of the cockpit.46 However, although the hijacking of Flight 11 “began at 8:14 or shortly thereafter,” the 9/11 Commission said, Sweeney’s call did not go through until 8:25.47 Her alleged call, in other words, described the hijacking as beginning over 11 minutes after it, according to the official timeline, had been successfully carried out.

Multiple lines of evidence, therefore, imply that the cell phone calls were faked. This fact has vast implications, because it implies that all the reported calls from the planes, including those from onboard phones, were faked. Why? Because if the planes had really been taken over in surprise hijackings, no one would have been ready to make fake cell phone calls.

Moreover, the FBI, besides implying, most clearly in the case of Deena Burnett, that the phone calls reporting the hijackings had been faked, comes right out and says, in its report about calls from Flight 77, that no calls from Barbara Olson occurred. It does mention her. But besides attributing only one call to her, not two, the FBI report refers to it as an “unconnected call,” which (of course) lasted “0 seconds.”48 In 2006, in other words, the FBI, which is part of the Department of Justice, implied that the story told by the DOJ’s former solicitor general was untrue. Although not mentioned by the press, this was an astounding development.

This FBI report leaves only two possible explanations for Ted Olson’s story: Either he made it up or else he, like Deena Burnett and several others, was duped. In either case, the story about Barbara Olson’s calls, with their reports of hijackers taking over Flight 77, was based on deception.

The opening section of The 9/11 Commission Report is entitled “Inside the Four Flights.” The information contained in this section is based almost entirely on the reported phone calls. But if the reported calls were faked, we have no idea what happened inside these planes. Insofar as the idea that the planes were taken over by hijackers who looked “Middle Eastern,” even “Islamic,” has been based on the reported calls, this idea is groundless.

4. Was the Presence of Hijackers Proved by a Radio Transmission “from American 11”?

It might be objected, in reply, that this is not true, because we know that American Flight 11, at least, was hijacked, thanks to a radio transmission in which the voice of one of its hijackers is heard. According to the 9/11 Commission, the air traffic controller for this flight heard a radio transmission at 8:25 AM in which someone—widely assumed to be Mohamed Atta—told the passengers: “We have some planes. Just stay quiet, and you’ll be okay. We are returning to the airport.” After quoting this transmission, the Commission wrote: “The controller told us that he then knew it was a hijacking.”49 Was this transmission not indeed proof that Flight 11 had been hijacked?

It might provide such proof if we knew that, as the Commission claimed, the “transmission came from American 11.”50 But we do not. According to the FAA’s “Summary of Air Traffic Hijack Events,” published September 17, 2001, the transmission was “from an unknown origin.”51 Bill Peacock, the FAA’s air traffic director, said: “We didn’t know where the transmission came from.”52 The Commission’s claim that it came from American 11 was merely an inference. The transmission could have come from the same room from which the calls to Deena Burnett originated.

Therefore, the alleged radio transmission from Flight 11, like the alleged phone calls from the planes, provides no evidence that the planes were taken over by al-Qaeda hijackers.

5. Did Passports and a Headband Provide Evidence that al-Qaeda Operatives Were on the Flights?

However, the government’s case for al-Qaeda hijackers on also rested in part on claims that passports and a headband belonging to al-Qaeda operatives were found at the crash sites. But these claims are patently absurd.

A week after the attacks, the FBI reported that a search of the streets after the destruction of the World Trade Center had discovered the passport of one of the Flight 11 hijackers, Satam al-Suqami.53 But this claim did not pass the giggle test. “[T]he idea that [this] passport had escaped from that inferno unsinged,” wrote one British reporter, “would [test] the credulity of the staunchest supporter of the FBI’s crackdown on terrorism.”54

By 2004, when the 9/11 Commission was discussing the alleged discovery of this passport, the story had been modified to say that “a passer-by picked it up and gave it to a NYPD detective shortly before the World Trade Center towers collapsed.”55 So, rather than needing to survive the collapse of the North Tower, the passport merely needed to escape from the plane’s cabin, avoid being destroyed or even singed by the instantaneous jet-fuel fire, and then escape from the building so that it could fall to the ground! Equally absurd is the claim that the passport of Ziad Jarrah, the alleged pilot of Flight 93, was found at this plane’s crash site in Pennsylvania.56 This passport was reportedly found on the ground even though there was virtually nothing at the site to indicate that an airliner had crashed there.

The reason for this absence of wreckage, we were told, was that the plane had been headed downward at 580 miles per hour and, when it hit the spongy Pennsylvania soil, buried itself deep in the ground. New York Times journalist Jere Longman, surely repeating what he had been told by authorities, wrote: “The fuselage accordioned on itself more than thirty feet into the porous, backfilled ground. It was as if a marble had been dropped into water.”57 So, we are to believe, just before the plane buried itself in the earth, Jarrah’s passport escaped from the cockpit and landed on the ground. Did Jarrah, going 580 miles per hour, have the window open?58 Also found on the ground, according to the government’s evidence presented to the Moussaoui trial, was a red headband.59 This was considered evidence that al-Qaeda hijackers were on Flight 93 because they were, according to some of the phone calls, wearing red headbands. But besides being absurd for the same reason as was the claim about Jarrah’s passport, this claim about the headband was problematic for another reason. Former CIA agent Milt Bearden, who helped train the Mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan, has pointed out that it would have been very unlikely that members of al-Qaeda would have worn such headbands:

[The red headband] is a uniquely Shi’a Muslim adornment. It is something that dates back to the formation of the Shi’a sect. . . . [I]t represents the preparation of he who wears this red headband to sacrifice his life, to murder himself for the cause. Sunnis are by and large most of the people following Osama bin Laden [and they] do not do this.60

We learned shortly after the invasion of Iraq that some people in the US government did not know the difference between Shi’a and Sunni Muslims. Did such people decide that the hijackers would be described as wearing red headbands?

6. Did the Information in Atta’s Luggage Prove the Responsibility of al-Qaeda Operatives?

I come now to the evidence that is said to provide the strongest proof that the planes had been hijacked by Mohamed Atta and other members of al-Qaeda. This evidence was reportedly found in two pieces of Atta’s luggage that were discovered inside the Boston airport after the attacks. The luggage was there, we were told, because although Atta was already in Boston on September 10, he and another al-Qaeda operative, Abdul al-Omari, rented a blue Nissan and drove up to Portland, Maine, and stayed overnight. They caught a commuter flight back to Boston early the next morning in time to get on American Flight 11, but Atta’s luggage did not make it.

This luggage, according to the FBI affidavit signed by James Lechner, contained much incriminating material, including a handheld flight computer, flight simulator manuals, two videotapes about Boeing aircraft, a slide-rule flight calculator, a copy of the Koran, and Atta’s last will and testament.61 This material was widely taken as proof that al-Qaeda and hence Osama bin Laden were behind the 9/11 attacks.

When closely examined, however, the Atta-to-Portland story loses all credibility.

One problem is the very idea that Atta would have planned to take all these things in baggage that was to be transferred to Flight 11. What good would a flight computer and other flying aids do inside a suitcase in the plane’s luggage compartment? Why would he have planned to take his will on a plane he planned to crash into the World Trade Center?

A second problem involves the question of why Atta’s luggage did not get transferred onto Flight 11. According to an Associated Press story that appeared four days after 9/11, Atta’s flight “arrived at Logan . . . just in time for him to connect with American Airlines flight 11 to Los Angeles, but too late for his luggage to be loaded.”62 The 9/11 Commission had at one time evidently planned to endorse this claim.63 But when The 9/11 Commission Report appeared, it said: “Atta and Omari arrived in Boston at 6:45” and then “checked in and boarded American Airlines Flight 11,” which was “scheduled to depart at 7:45.”64 By thus admitting that there was almost a full hour for the luggage to be transferred to Flight 11, the Commission was left with no explanation as to why it was not.

Still another problem with the Atta-to-Portland story was the question why he would have taken this trip. If the commuter flight had been late, Atta, being the ringleader of the hijackers as well as the intended pilot for Flight 11, would have had to call off the whole operation, which he had reportedly been planning for two years. The 9/11 Commission, like the FBI before it, admitted that it had no answer to this question.65

The fourth and biggest problem with the story, however, is that it did not appear until September 16, five days after 9/11, following the collapse of an earlier story.

According to news reports immediately after 9/11, the incriminating materials, rather than being found in Atta’s luggage inside the airport, were found in a white Mitsubishi, which Atta had left in the Boston airport parking lot. Two hijackers did drive a blue Nissan to Portland and then take the commuter flight back to Boston the next morning, but their names were Adnan and Ameer Bukhari.66 This story fell apart on the afternoon of September 13, when it was discovered that the Bukharis, to whom authorities had reportedly been led by material in the Nissan at the Portland Jetport, had not died on 9/11: Adnan was still alive and Ameer had died the year before.67

The next day, September 14, an Associated Press story said that it was Atta and a companion who had driven the blue Nissan to Portland, stayed overnight, and then taken the commuter flight back to Boston. The incriminating materials, however, were still said to have been found in a car in the Boston airport, which was now said to have been rented by “additional suspects.”68 Finally, on September 16, a Washington Post story, besides saying that the Nissan had been taken to Portland by Atta and al-Omari, specified that the incriminating material had been found in Atta’s luggage inside the Boston airport.69

Given this history of the Atta-to-Portland story, how can we avoid the conclusion that it was a fabrication?

7. Were al-Qaeda Operatives Captured on Airport Security Videos?

Still another type of evidence for the claim that al-Qaeda operatives were on the planes consisted of frames from videos, purportedly taken by airport security cameras, said to show hijackers checking into airports. Shortly after the attacks, for example, photos showing Atta and al-Omari at an airport “were flashed round the world.”70 However, although it was widely assumed that these photos were from the airport at Boston, they were really from the airport at Portland. No photos showing Atta or any of the other alleged hijackers at Boston’s Logan Airport were ever produced. We at best have photographic evidence that Atta and al-Omari were at the Portland airport.

Moreover, in light of the fact that the story of Atta and al-Omari going to Portland was apparently a late invention, we might expect the photographic evidence that they were at the Portland Jetport on the morning of September 11 to be problematic. And indeed it is. It shows Atta and Omari without either jackets or ties on, whereas the Portland ticket agent said that they had been wearing jackets and ties.71 Also, a photo showing Atta and al-Omari passing through the security checkpoint is marked both 05:45 and 05:53.72

Another airport video was distributed on the day in 2004 that The 9/11 Commission Report was published. The Associated Press, using a frame from it as corroboration of the official story, provided this caption:

Hijacker Khalid al-Mihdhar . . . passes through the security checkpoint at Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Va., Sept. 11 2001, just hours before American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon in this image from a surveillance video.73

Continued

David Ray Griffin is Emeritus Professor of Philosophy of Religion at Claremont School of Theology and Claremont Graduate University. He has published 34 books, including seven about 9/11, most recently The New Pearl Harbor Revisited: 9/11, the Cover-Up, and the Exposé (Northampton: Olive Branch, 2008).

![U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry on Aug. 30, 2013, claims to have proof that the Syrian government was responsible for a chemical weapons attack on Aug. 21, 2013, but that evidence failed to materialize or was later discredited. [State Department photo]](https://consortiumnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/kerry-syria-remarks-300x199.jpg)