By the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries Africans in the newly-formed United States were in rebellion against slavery. Since 1619 under British rule there had been a rising stream of indentured servants and enslaved persons fueling the agricultural and industrial growth of the country.

Incorporated as a state within the union in 1837, the areas now known as Detroit and Michigan also engaged in the peculiar institution dating back to the closing decades of the 18th century. Many of the streets that we travel on daily were named after white men who owned enslaved Africans.

People such as Joseph Campeau and John R. Williams who are considered the founding fathers of the city of Detroit owned Africans. Although those born in the Northwest Territory and later Michigan were ostensibly free persons, this was not extended to people transported into the area by landowning whites.

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, second from right, with other panelists on Sat. Oct. 29, 2016

Canada as a North American territory still under British domination in the early decades of the 19th century, also allowed slavery up until the 1833 Abolition of Slavery Act imposed on the territories of the English crown. As early 1772 in England itself as a result of the decision in the Somerset v. Stewart case, there were reforms to the slave system. By 1806, the British had legally abolished the trade in enslaved Africans. Although the U.S. Congress ostensibly banned the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, the practice continued internally for another five decades or more. However, the system of slavery did not recede but expanded between the first decades of the 19th century to the time of the U.S. Civil War.

By the time of the Blackburn Rebellion there were already well over 100 African people residing in the city. Most had come from the southern regions of the country fleeing from the plantation system of agricultural production.

Rebellion in Early Years of the 1800s

The number of enslaved Africans increased immensely between 1800 and 1833. Census figures indicate that the trade in human cargo had produced large numbers of people who essentially remained stateless and subject to the super-exploitation, torture and transferal of the dominant slave-owning class. At the turn of the 19th century there were less than one million enslaved Africans in the U.S. However, by 1830 the number had risen to approximately 2.1 million.

Accompanying the escalation in the number of Africans enslaved in the U.S. was various forms of resistance including rebellion. The Haitian Revolution beginning in 1791 and extending to the declaration of independence for the Black Republic in 1804, served as an inspiration to other enslaved nations throughout the Western hemisphere.

In 1800, an insurrection plot was uncovered in Richmond, Virginia said to have been led by Gabriel, a literate African skills tradesman, who was influenced by developments in Haiti.

Gabriel was captured, imprisoned and hung in response to the failure of the rebellion. Nonetheless, these historical events are said to have changed the course of the debate over African slavery in the U.S. Those who feared the demise of the system of chattel slavery worked incessantly to stiffen laws aimed at preventing insurrection. Others in opposition to slavery pointed to the plot as evidence that the system had to be eliminated.

The Blackpast.org website provides a summary account of the plot led by Gabriel and numerous other fellow enslaved Africans. It says based upon the historical research conducted by Herbert Aptheker that, “Prosser [the surname of his owners] and the other revolt leaders were probably influenced by the American Revolution and more recently the French and Haitian Revolutions with their rhetoric of freedom, equality and brotherhood. In the months prior to the revolt Prosser recruited hundreds of supporters and organized them into military units. Although Virginia authorities never determined the extent of the revolt, they estimated that several thousand planned to participate including many [of whom] were to be armed with swords and pikes made from farm tools by slave blacksmiths.”

This same report also emphasized: “Prosser [the name of his owners] planned to initiate the insurrection on the night of August 30, 1800. However, earlier in the day two slaves who wanted to protect their masters betrayed the plot to Virginia authorities. Governor James Monroe alerted the militia. A rainstorm delayed the uprising by 24 hours, preventing Prosser’s army from assembling outside Richmond and providing the militia crucial time to prepare a defense of the city. Realizing their plan had been discovered, Prosser and many of his followers dispersed into the countryside. About 35 leaders were captured and executed but Prosser escaped to Norfolk where he was betrayed by fellow slaves who claimed the reward for his capture on September 25. Prosser was returned to Richmond and tried for his role in the abortive uprising. He was found guilty on October 6, 1800 and executed the following day.”

Some 11 years later in Louisiana, another rebellion was staged led by an African who could trace his ancestral lineage to the area in West Africa now known as Ghana. Some historians have speculated that Charles Deslondes, the leader, had lived in Haiti as well being influenced by the Revolution and coming to the U.S. with his master during an exodus by whites from San Domingo after the seizure of power and the establishment of a republic.

Rhae Lynn Barnes wrote of the uprising which began on January 10, 1811 noting: “Although the slaves under Deslondes’s leadership possessed very few firearms, they engaged in combat with the local militia led by General Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), a plantation owner, three days after the rebellion began. Hampton had responded to a call from William C. C. Claiborne, the governor of the Territory of Orleans, to suppress the revolt. A second brigade from Baton Rouge, under the command of Major Homer Virgil Milton, was also roused to combat the slaves. The two militias merged the following morning, 11 January 1811, near Francois Bernard Bernoudi’s plantation. The slaves fought with pikes, hoes, and axes. They carried banners, marched to the beat of drums, and were broken into subunits that each had individual leaders on horseback. The slaves wreaked havoc on the region, set plantations on fire as they marched towards New Orleans, and recruited additional slaves, while white residents fled to the city of New Orleans or the backwoods nearer their plantations. At the end of two days’ fighting the militias had largely quelled the rebellion and captured Deslondes and other rebels. Some estimates from white officials and journalists at the time claimed that sixty-six rebels were killed, with a further sixteen arrested and seventeen missing, though that number may have been higher.”

This same author later explains that: “Beginning on 13 January 1811, a two-day tribunal was held at the Destrehan Plantation under the jurisdiction of St. Charles Parish judge Pierre Bauchet St. Martin to determine what should be done with the remaining slaves. As the slave rebels were not equipped with firearms, the militia had killed at least sixty of them, and wounded many more. The tribunal sentenced sixteen of the rebellion leaders for execution. The tribunal also decapitated them and displayed their heads along the river.”

These Africans had rose up against their plantation owners and marched in military formation towards New Orleans with the expressed intent to seize control of weapon depots and leading an insurrection to end slavery. Such incidents proved that Africans were committed to gaining their freedom despite the threat of capture, torture and death.

New Orleans, Louisiana, like the Richmond area in Virginia, was a major entry point into the U.S. for enslaved Africans even under British and French rule. A long term insurrection in either of these locations would have proved disastrous for the system of slavery in North America.

Later in 1822, another plot was uncovered in Charleston, South Carolina, centered-around the second oldest African Methodist Episcopal Church. Telemaque, also known as Denmark Vessey, was said to have been the leader. The discovery of the insurrection plot prompted the banning of the church in Charleston until after the conclusion of the Civil War over four decades later.

Telemaque may have also lived in Haiti during the tumultuous period leading up to the African revolution. His name Denmark possibly derived from his tenure in the Virgin Islands then under Danish control. Such historical intersections between the Caribbean and Southern U.S. developments suggest a Pan-African consciousness which evolved in the antebellum era. Many Africans resisted the slave system through various forms of non-cooperation and outright disruption.

Of course, the Nat Turner Rebellion of August 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia has been illuminated through the Nate Parker film “The Birth of a Nation.” Nat had been a preacher and traveled to various plantations and towns. In the film it illustrates how the clergy has been used by the ruling class to convince the enslaved to accept their plight as oppressed people.

Flight, Resistance by Institution Building and the Quest for Political Power

Opposition to slavery was exemplified as well through flight from the plantations and work settings. Evidence of this being a major problem during the antebellum period is reflected in the numerous ads taken out in Southern and Northern newspapers by plantation owners and their agents asking for information on what was considered escaped property.

Various law-enforcement agencies arose with the expressed intent of capturing and containing the African population. Laws against the flight and disobedience of enslaved Africans stiffened as the 1830s came into being.

In most cases deliberate rebellion and insurrection was not feasible therefore other forms of resistance arose through the running away from slavery and the establishment of African communities in non-slave owning states. Other forms of resistance were representative of the formation of independent African organizations and religious institutions.

The African Baptist Church was initially organized under British colonial rule in Georgia, South Carolina and Virginia in 1773-74. There are disputes over whether the church had its origins in Virginia or Georgia. Nonetheless, these institutions represented the desire for independent existence and self-determination.

After the American settlers revolted against the British in 1776, Africans who were members of the First Baptist Church took refuge behind British military lines. After the intensification of the war, many Africans were evacuated from Savannah and were relocated in Nova Scotia. Later others were transported to the West African region now known as Sierra Leone. They would establish a British outpost for a century-and-a-half until the African independence movements sweep the continent during the 1950s and 1960s.

In the city of Philadelphia in the Northeast of the U.S., the Free African Society and the African Methodist Episcopal Church were formed over a number of years between the late 1780s and the two decades of the 19th century. The Mother Emmanuel Church of Charleston, South Carolina, is recorded as the second AME Church founded in the U.S. The first institution in Philadelphia was formed by figures such as Paul Allen, Sara Allen and Absalom Jones.

Another important figure in the African resistance movements both in regard to political agitation and emigration was Paul Cuffe (Kofi). Cuffe was born in Massachusetts in the late 1750s. He was of Ashanti descent, originating in the West African region now known as Ghana. Cuffe became involved in politics when he was in his 20s by leading a campaign which petitioned the newly-independent colony of Massachusetts to either grant full citizenship rights to African people or cease taxing them.

Although the political effort was not successful at the time by 1783 when the state constitution was adopted it proclaimed full rights for all “citizens.” Soon enough Cuffe became wary of the capacity of Africans to gain complete freedom in the U.S.

He had trained as a sailor and later purchases a shipping line becoming the most prosperous African in the country by 1811. Cuffe became an advocate of emigration to the British colony of Sierra Leone where Africans had been transported in the aftermath of the American insurrection of 1776-1783.

The Blackpast.org website says of Cuffe and his emigration efforts that he was “Inspired by British abolitionists who had established Sierra Leone, Cuffe began to recruit Blacks to emigrate to the fledgling colony. On January 2, 1811, he launched his first expedition to Sierra Leone, sailing with an all-African American crew to Freetown. While there Cuffe helped to establish ‘The Friendly Society of Sierra Leone,’ a trading organization ran by African Americans who had returned to West Africa. Cuffe and others hoped the success of this enterprise would generate a mass emigration of free Blacks to West Africa who, once there, would evangelize the Africans, establish business enterprises, and work to abolish slavery.”

This entry goes on revealing: “In 1815 Cuffe led 38 African American colonists to Sierra Leone. The colonists established new homes and integrated into the small community of former English residents and refugees from Nova Scotia. Cuffe hoped to organize larger groups of black emigrants. Cuffe’s efforts, however, were soon eclipsed by the larger and much better funded American Colonization Society (ACS), founded in 1816, which promoted a similar scheme that eventually created the colony of Liberia. As white and Black Americans debated the merits of the ACS’s mass emigration program, Cuffe’s earlier efforts were soon eclipsed. Paul Cuffe died on September 9, 1817.”

The Detroit Blackburn Rebellion and Its Political Significance

Consequently, the African population in the U.S. was by the second and third decades of the 19th century creating the basis for a protracted struggle for liberation. Utilizing various forms of resistance including rebellion, flight, emigration and the fight for political rights and independence, this movement was utilizing all of the tools of the evolving capitalist society.

Therefore it is not surprising that by the early 1830s Detroit had become a center of African migration through flight from slavery and the escalating struggle to end involuntary servitude in both the North and the South. Others on the panel have provided a much more detailed account of the specific circumstances leading to the migration of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn to Detroit from Kentucky along with the chronological development of the heroic breaks from detention, the flight to Canada and the political and legal work that led to their ability to have refuge in the country as well as the pioneering professional successes of the family in the newly-incorporated City of Toronto.

Our emphasis is on examining the social dynamics of the migration and settlement along with the impact of the already failing system of slavery in the South as well as other regions of the U.S. Detroit experienced exponential population growth during the period of 1830 to 1840, from approximately 2,200 at the beginning of the decade, to 4,900 by its conclusion.

The African population officially had grown from 67 in 1820 to 126 in 1830 (5.6 percent) and by the end of the decade it stood at 193 (2.1 percent). As early as the 1830s Detroit was emerging as a major commercial hub being strategically located on the River which flowed into the Great Lakes.

Flour milling and a nascent ocean-going cargo ship repair and building industry sprung up during the 1830s. By the 1840s, the city’s shipyards were among the first to build steam-powered vessels.

Detroit was not alone in moving away from the reliance on farming and slavery to mass production, along with interstate and international trade in commodities. This burgeoning industrialization would eventually place further strains on slavery as an economic system.

The slave system was revitalized after the 1793 invention of the cotton gin addressing the demand for raw material in the textile industry which flourished. Eli Whitney is reported to have taken the idea for the cotton gin from an enslaved African. This new technology also drove the demand for slave labor through the period of the middle decades of the 19th century.

As the 19th century unfolded the growth in the cotton industry led to the further concentration of slave ownership by a relatively small group of planters as the European settlers moved westward. In various areas of the antebellum South very few whites owned Africans and many were landless. The reliance on slave labor in the production of cotton was instrumental in the growth of industrialization in Europe and the Northern states of the U.S. However, this economic specialization in raw material supplying stifled the development of industrial production and its concomitant sectors such as communications, transportation and the acquisition of new skills. In order for the system to survive there was the need to expand slavery to other U.S.-acquired territories and states across North America. Therefore, a struggle between the slave-owning South and the rapidly industrializing North ensued.

Under such expansive conditions many Africans fled the plantations for northern cities where they could work in other sectors of the economy. Those who fled were by no means completely free from national oppression, false imprisonment and being captured by agents of the planters in order to be turned back over into slavery.

Africans in addition to the flight from slavery and rebellions against the planter class, served as some of the first advocates for the legal abolition of the system. The earliest known African newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, founded in 1827 by John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish in New York City, was a staunch anti-slavery periodical.

Others such as Maria W. Stewart of Boston was influenced by the militant outspoken writer David T. Walker who drafted and published an appeal in 1829 demanding the end of slavery and national oppression against the African people. Stewart is cited as one of the first women of any race to deliver public speeches. She spoke and wrote extensively in opposition to slavery beginning in 1832.

Stewart’s father had worked with William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist and publisher of The Liberator newspaper beginning in early 1831. Stewart’s articles appeared in The Liberator which was distributed across the U.S. and internationally.

A report on Stewart’s contribution to the struggle for African and women’s emancipation is published on the African American Registry saying: “In her first address, in 1832, Stewart spoke before a women-only audience at the African American Female Intelligence Society, an institution founded by the free Black community of Boston. Speaking to that female Black audience, she used the Bible to defend her right to speak, and spoke on both religion and justice, advocating activism for equality. The text of the talk was published in Garrison’s newspaper on April 28, 1832. On September 21, 1832, Stewart delivered a second lecture, this time to an audience that also included men. She spoke at Franklin Hall, the site of the New England Anti-Slavery Society meetings. In her speech, she questioned whether free Blacks were much more free than slaves, given the lack of opportunity and equality. She also questioned the move to send free Blacks back to Africa. Garrison published more of her writings in The Liberator. He published the text of her speeches there, putting them into the Ladies Department. In 1832, Garrison published a second pamphlet of her writings as Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart. On February 27, 1833, she delivered her third public lecture, ‘African Rights and Liberty,’ at the African Masonic Hall. Her fourth and final Boston lecture before moving to New York was a “Farewell Address” on September 21, 1833, when she addressed the negative reaction that her public speaking had provoked, expressing both her dismay at having little effect, and her sense of divine call to speak publicly.” (www.aaregistry.org)

Walker in his Appeal proclaimed that the conditions under which his people lived in 1829 were the worse of any oppressed nation in history. He says to the reader: “HAVING travelled over a considerable portion of these United States, and having, in the course of my travels, taken the most accurate observations of things as they exist–the result of my observations has warranted the full and unshaken conviction, that we, (colored people of these United States,) are the most degraded, wretched, and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began; and I pray God that none like us ever may live again until time shall be no more. They tell us of the Israelites in Egypt, the Helots in Sparta, and of the Roman Slaves, which last were made up from almost every nation under heaven, whose sufferings under those ancient and heathen nations, were, in comparison with ours, under this enlightened and Christian nation, no more than a cypher–or, in other words, those heathen nations of antiquity, had but little more among them than the name and form of slavery; while wretchedness and endless miseries were reserved, apparently in a phial, to be poured out upon our fathers, ourselves and our children, by Christian Americans!” (Preamble)

Ending this document which includes four pamphlets published by Walker, the author stresses again: “In conclusion, I ask the candid and unprejudiced of the whole world, to search the pages of historians diligently, and see if the Antideluvians–the Sodomites–the Egyptians–the Babylonians–the Ninevites–the Carthagenians–the Persians–the Macedonians–the Greeks–the Romans–the Mahometans–the Jews–or devils, ever treated a set of human beings, as the white Christians of America do us, the Blacks, or Africans. I also ask the attention of the world of mankind to the declaration of these very American people, of the United States.”

Walker’s Appeal, the speeches and writings of Maria W. Stewart, the African revolt in Southampton County, Virginia in 1831 and the subsequent rebellions and other forms of flight and political agitation, point clearly in the direction of an eventual civil war to end slavery. The participation of Africans in the war to end legalized slavery was considerable and decisive to the Union victory of 1865. It was the African troops which liberated Richmond the last capital of the Confederacy which collapsed several days later after retreating southern soldiers set fires in the city in April 1865.

Emigration of African people, self-determination and the agitation for democratic rights were not necessarily mutually exclusive as forms of resistance. Journalist, educator and eventual lawyer, Mary Ann Shadd Carey, published a monograph in Detroit during 1852 advocating resettlement in Canada. This pioneering Black woman had relocated in Canada after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which endangered the already precarious status of any person of African descent enslaved or “free.”

Nevertheless, after the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 and its going into effect on January 1, 1863, Shadd Carey crossed back over into the U.S. to serve as a recruitment officer for Africans entering the Union army. The struggle of the African people in North America has been a multi-faceted one depending upon the objective and subjective factors involving race relations and economic developments.

Implications for Detroit’s Racial History and the Political Future of North America

The three decades after the Blackburn Rebellion would witness Detroit becoming a more populated city due to the migration from Europe and the Southern states. Growth in the production of marine ship engines for export by the 1840s led to more people moving into the area.

By the 1860s, Detroit was a leading source of copper production for domestic use and export. For two decades copper smelting and refining from ores became the leading industry in the city.

In 1861, the Civil War erupted after the President Abraham Lincoln ordered an attack on a military installation held by Confederates at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. By late 1862, the threat of a Confederate victory was very much in evidence. Plans were made for the evacuation of the president from Washington, D.C. Lincoln by this time had no other choice than to institute a draft and allow the induction of Africans into the Union army.

The passage by Congress of the Military Conscription Act on March 3, 1863 gave rise to social tensions throughout many Northern cities. Just three days later the African community in Detroit was attacked by white mobs in the aftermath of a racially-charged two day trial of William Faulkner, a business owner, who was accused of sexually assaulting two young girls, one white and the other Black.

Having been found guilty on the second day of the trial, Faulkner, while leaving the courtroom, was set upon by a racist mob. Guards escorting Faulkner to the jail were hit with projectiles. When one of the guards fired into the crowd a German man was killed. This set off the mob which began to attack copper businesses and other establishments owned by Africans in what is now known as the downtown area.

In the attack on one of the coppersmith businesses, an African man was axed to death. The Africans inside the building returned fire. Later mobs of whites ran through the African community assaulting residents and setting houses ablaze. The military units stationed in nearby Ypsilanti were deployed and by the following morning the unrest had been put down.

Personal accounts of the race terror indicated the level of hatred toward Africans at the height of the Civil War. The Detroit Free Press, which was a Democratic Party publication, was blamed for fanning hatred towards the African community.

Many Africans fled from the Detroit area into surrounding communities and Ontario, Canada. This process of racial attacks on the African community was repeated four months later with greater vigor in New York City where 1,000 Black people including children were killed in days of racist terror.

Nevertheless, by the 1880s, the copper resources were depleted. The city through its mining of copper, manufacturer of steam engines for ships led to other forms production including carriages for transportation. Under such circumstances the city was poised for the expansion of the automotive industry in the first decades of the 20th century.

This industrial growth brought about a rapid migration into Detroit. Consequently, the African American population grew by leaps and bounds during 1910-1920.

Despite these advances in technology, racism and national oppression remained in force. Housing for many recent arrivals was segregated and substandard. The city leaders sought to maintain racial dominance through super-exploitation, police brutality and dividing of the Black and White working class people.

City administrations, industrial firms, real estate brokers, and all other established institutions in Detroit were bastions of racial discrimination. The Great Depression which struck in 1929 was particularly devastating for Detroit due to its industrial base. Joblessness, home evictions and hunger were rife. Popular struggles flourished in the early 1930s, where communist and left-wing labor demonstrations demanded an end to evictions, jobs, relief and food.

With the outbreak of World War II, the situation worsened as a result of increased migration amid a shortage of housing and recreational space. In 1942, the government-built Sojourner Truth Homes on the city’s eastside became battleground where whites sought to prevent African Americans from moving into the complex.

The following year in June 1943, one of the worst episodes of racial unrest erupted prompting the authorities to deploy the military to restore order. Over 30 people were killed, the majority of whom were African Americans. Whites attacked African Americans on the major streets of the city while the community formed self-defense units to stave off the onslaught of racist terror.

After the War in the late 1940s, an urban removal plan was enacted designed to relocate African Americans from the lower eastside of the city. This process took a decade-and-a-half to complete so by the early 1960s, the areas known as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley had been razed making way for expressways and new housing complexes.

Many objected to this forced removal to no avail. The U.S. government had established a GI Bill for returning white soldiers which provided credit for the rapid suburbanization of the region. During the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Federal Highway Administration was created providing funds from the government to build expressways which facilitated the dislocation of communities in Detroit and across the U.S.

Detroit has been at the center of racial unrest and mass resistance for the last 185 years. Therefore, the July 1967 Rebellion, the largest up until that time in U.S. history, was not a surprising event. This was a highly-politicized outbreak of unrest rooted within the Black working class. Its impact is still felt today nearly five decades later.

Even with the decline in Detroit’s population which stems from the restructuring of the world capitalist system beginning during the late 1950s and extending to 1975, the city remains a center for racial domination, national oppression, gross economic exploitation and in response, organized resistance based upon self-determination and independent mass mobilization.

The second decade of the 21st century is touted by the ruling class and its corporate media pundits as the “end of history” in Detroit. However, there are too many unknown factors in ruling class politics and mass working class initiatives to predict the political future of the city. Racial tensions remain and are rising. If events in Ferguson, Baltimore, Milwaukee and Charlotte are any indication of the nature of race relations in the U.S., then the city of Detroit will continue as a source of conflict as well as potential solutions to the ongoing crises of inequality and undemocratic governance.

Note: This address was delivered at a panel discussion on Saturday October 29, 2016 at the Skillman Branch of the Detroit Public Library downtown. The event was held to honor the location of the historic Blackburn Rebellion of 1833 where Africans and their supporters liberated two fugitive enslaved persons facilitating their transport to neighboring Canada.

The library was built in 1931 on the same land as the former jail where Lucie and Thornton Blackburn were broken free after they were captured by slave catchers in an effort to send them back into bondage in the state of Kentucky. This story is told in a recent book entitled “A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland”, edited by Karolyn Smardz Frost and Veta Smith Tucker. Frost presented as well on the panel. Other panelists were David Goldstein of the United States National Park Service; Prof. Roy Finkenbine, co-chair of the History Department at the University of Detroit-Mercy campus;

Prof. DeWitt Dykes of the History Department at Oakland University; Ms. Elsie Harding-Davis, an internationally-recognized African Canadian Heritage Consultant; Jamon Jordan, owner of Black Scroll Network History & Tours and President of the Detroit chapter of the Association for the Study of African American Life & History (ASALH). The panel was assembled and moderated by Ms. Kimberly L. Simmons, President and Executive Director of the Detroit River Project who is also a contributor to the aforementioned book.

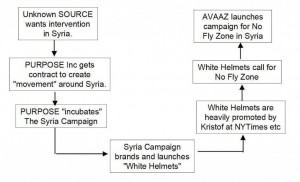

Backed by the Obama White House, Clinton and the media felt they had a green light to keep pressing ahead with blaming Russia – not only for the controversial DNC leaks, but also for hacking into

Backed by the Obama White House, Clinton and the media felt they had a green light to keep pressing ahead with blaming Russia – not only for the controversial DNC leaks, but also for hacking into

These are just a few scandals surrounding the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign, along with the many exposés revealed through Wikileaks, and the Podesta email batches. Those are actual scandals with real tangible evidence – unlike the ‘Russians hacking the DNC and John Podesta and passing those to Wikileaks.’ Suffice to say, the Democratic Party machine has already demonstrated that it is prepared to say anything in order to deflect and divert attention away from the damning Wikileaks material, and also blame Donald Trump in the process. It should be obvious by now that in their desperation to push a highly comprised Hillary Clinton over the finish line on November 8th, the Washington establishment has concocted the story that ‘Putin is trying to influence our electoral process in the US.’ They’ve tried to lay this at the feet of Donald Trump, who Obama and Clinton claim has some secret special relationship with Vladimir Putin. The liberal mainstream media have made a meal out of this talking point, and anti-Russian war hawks on the Republican side love it too. For the White House and the Clinton campaign this seemed like the ultimate clean sweep – a perfectdouble entendre.

These are just a few scandals surrounding the Democratic Party and the Clinton campaign, along with the many exposés revealed through Wikileaks, and the Podesta email batches. Those are actual scandals with real tangible evidence – unlike the ‘Russians hacking the DNC and John Podesta and passing those to Wikileaks.’ Suffice to say, the Democratic Party machine has already demonstrated that it is prepared to say anything in order to deflect and divert attention away from the damning Wikileaks material, and also blame Donald Trump in the process. It should be obvious by now that in their desperation to push a highly comprised Hillary Clinton over the finish line on November 8th, the Washington establishment has concocted the story that ‘Putin is trying to influence our electoral process in the US.’ They’ve tried to lay this at the feet of Donald Trump, who Obama and Clinton claim has some secret special relationship with Vladimir Putin. The liberal mainstream media have made a meal out of this talking point, and anti-Russian war hawks on the Republican side love it too. For the White House and the Clinton campaign this seemed like the ultimate clean sweep – a perfectdouble entendre.