All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Wants to Hear From You!

***

Imperialism, the worldwide expansion of capitalism, motivated by the lust for raw materials such as petroleum, markets and cheap labour, involved fierce competition among great powers such as the British Empire, czarist Russia, and the German Reich, and thus led to the Great War of 1914–1918, later to be known as the First World War or World War I.

The First World War was the product of the nineteenth century, a “long century” in the view of some historians, lasting from 1789 to 1914. It was characterized by revolutions of a political, social, and also economic nature, especially the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution, and ended with the emergence of imperialism, that is a new, worldwide manifestation of capitalism, originally a European phenomenon. This essay focuses on how imperialism played a decisive role in the outbreak, course, and outcome of the “Great War” of 1914–1918; it is based on the author’s book,

The Great Class War 1914–1918, James Lorimer, Toronto, 2016.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789, the nobility (or aristocracy) constituted the ruling class in just about every country in Europe. But because of the French Revolution and other revolutions that followed – not only in France – in 1830 and 1848, the haute bourgeoisie or upper-middle class was able, by the middle of the century, not to unseat the nobility, but to join it at the apex of the social and political pyramid. Thus was formed an “active symbiosis” of two classes that were in fact very different. The nobility was characterized by great wealth based on large landownership, had a strong preference for conservative political ideas and parties, and tended to cultivate clerical connections. The upper-middle class, on the other hand, favored the ideology and parties of liberalism as well as free-thinking and even anti-clericalism, and its wealth was generated by activities in commerce, industry, and finance. The two had been on opposite sides of the barricades during the revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848, when the bourgeoisie had been a revolutionary class and the aristocracy the counter-revolutionary class par excellence. What united these two propertied classes, namely in 1848, was their common fear of a class enemy that threatened their wealth, power, and privileges: the poor, restless, and potentially revolutionary “underclass,” propertyless and therefore known as the proletariat, the “people who own nothing but their offspring.”

The upper-middle class ceased to be revolutionary and joined the nobility on the counter-revolutionary side after the revolutions that shook Europe in 1848. Those events revealed that the lower classes aspired to bring about not only a political but also a social and economic revolution that would mean the end of the power and wealth of not only the nobility but also the bourgeoisie. In the second half of the nineteenth century, then, and until the outbreak of the First World War, the nobility and the haute bourgeoisie formed one single upper class, one single “elite” or “establishment.” But while the bourgeois bankers and industrialists enjoyed more and more economic power, political power tended to remain a monopoly of the aristocrats in most countries, and certainly in big, quasi-feudal empires such as Russia. In any event, all members of the elite were obsessed by the fear of revolution, increasingly embodied by proletarian political parties that subscribed to revolutionary Marxist socialism.

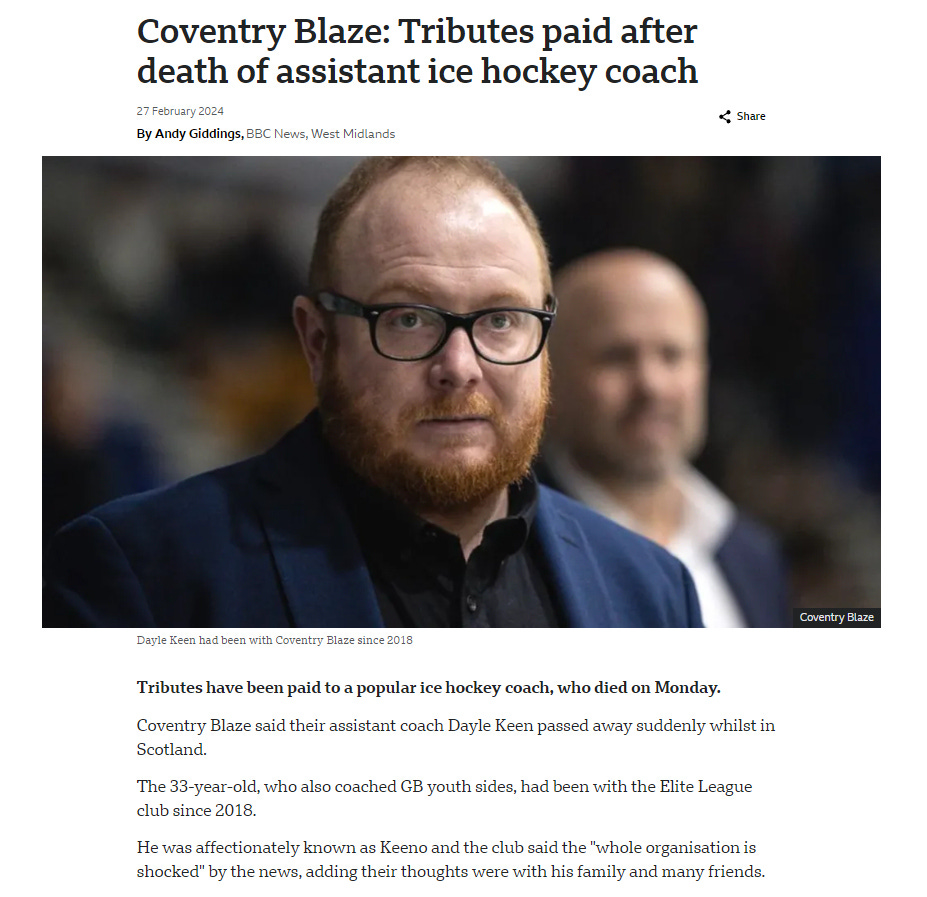

Illustrator T. Allom, Engraver J. Tingle – History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain by Sir Edward Baines (From the Public Domain)

The nineteenth century was also the century of the Industrial Revolution. In all countries where that revolution took place, the economy became much more productive. But this eventually caused the economic supply to exceed the demand, as was revealed in 1873 by the outbreak of a totally new kind of economic crisis, a crisis of overproduction. (Earlier economic crises had always been crises of underproduction, in which supply was insufficient in comparison to demand, for example, the infamous potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s.) In the most developed countries, that is, in Western and Central Europe and in the USA, countless small industrial producers disappeared from the economic scene as a result of this economic depression.

The industrial landscape was henceforth dominated by a relatively restricted group of gigantic enterprises, mostly incorporated, joint-stock companies or “corporations,” as well as associations of firms known as cartels, and also big banks. These “big boys” competed with each other, but increasingly, they also concluded agreements and collaborated in order to share scarce raw materials and markets, set prices, and find other ways to limit as much as possible the disadvantages of competition in a theoretically “free” market – and in order to defend and aggressively promote their common interests against foreign competitors and, of course, against workers and other employees. In this system, the big banks played an important role. They provided the credit required by large-scale industrial production and, at the same time, they looked all over the world for opportunities to invest the surplus capital made available by the megaprofits achieved by the corporations. Big banks thus became partners and even owners, or at least major shareholders, of corporations. Concentration, gigantism, oligopolies, and even monopolies characterized this new stage in the development of capitalism. Some Marxist writers have referred to this phenomenon as “monopoly capitalism.”

The industrial and financial bourgeoisie had hitherto been very much attached to the liberal, laissez-faire thinking of Adam Smith, which had assigned to the state only a minimal role in economic life, namely that of “night watch.” But now the role of the state was becoming increasingly important, for example, as buyer of industrial commodities, such as guns and other modern weapons, supplied by gigantic firms and financed by major banks. The industrial-financial elite also counted on the state’s intervention to protect the country’s corporations against foreign competition by means of tariffs on the importation of finished products, even though this violated the classical liberal dogma of free markets and free competition. (It is one of the ironies of history that the USA, today the world’s most fervent apostle of free trade, was extremely protectionist at that time.) “National economic systems” or “national economies” thus emerged, and they proceeded to compete fiercely against each other. State intervention – to be labelled “dirigism” or “statism” by economists – was now also favored because only a strong state was able to acquire foreign territories useful or even indispensable to industrialists and bankers as markets for their finished products or investment capital and as sources of raw materials and cheap labor. These desiderata were not normally available domestically, or at least not in sufficient quantities or at sufficiently low prices, they privileged a country’s industrialists and bankers vis-à-vis foreign competitors, and they helped to maximize profitability.

The kind of territorial acquisitions that could only be achieved under the auspices of a strong and interventionist state, also suited the nobility, the partner of the industrial-financial bourgeoisie within the ruling elite, and in many if not most countries still the class with a near-monopoly of political power. The aristocrats were traditionally large landowners, so it is only natural that they favored territorial acquisitions; the more acreage one controlled, the better. In noble families, moreover, the eldest son traditionally inherited not only the title but the family’s entire patrimony. Newly acquired territory overseas or – in the case of Germany and the Danube Monarchy – in Eastern Europe could function as “lands of unlimited possibilities” where the younger sons could acquire domains of their own and lord it over natives who were to serve as underpaid peasants or domestic servants, just as the Iberian Peninsula’s Reconquista had provided “castles in Spain” to junior aristocrats during the Middle Ages, the nobility’s golden age. Adventurous scions of noble families could also embark on prestigious careers as officers in conquering colonial armies or as high-ranking officials in the administration of colonial territories. (The highest functions in the colonies, for example, that of Viceroy of British India or Governor General of Canada, were indeed reserved almost exclusively for members of aristocratic families.) Finally, the nobility had started to invest heavily in capitalist activities such as mining, a branch of industry interested in overseas regions rich in minerals. The British and Dutch royal families thus acquired enormous portfolios of shares in firms that were prospecting for oil all over the world, such as Shell, so they too were likely to profit from territorial expansion.

Like its upper-middle class partner in the elite, the nobility could also expect to gain from territorial expansion in yet another way; such expansion proved useful as a means to exorcize the spectre of revolution, namely by co-opting potentially troublesome members of the lower orders and integrating them into the established order. How was this achieved?

First but not foremost, considerable numbers of proletarians could be put to work in colonized lands as soldiers, employees, and foremen on plantations and in mines (where the natives served as slaves), low-ranking bureaucrats in the colonial administration, and even missionaries. There they could not only enjoy a higher standard of living than at home but also a certain amount of social prestige, since they could lord it over, and feel superior to, the colored natives. Thus, they became more likely to identify with the state that made this form of social climbing possible and to be integrated into its established order. Second, within the mother countries themselves, a similar socialization of an even larger segment of the lower orders resulted from the acquisition of colonies. The ruthless “super-exploitation” that was possible in the colonies, whose denizens were robbed of their gold, their land, and other riches, and be made to slave away for virtually nothing, yielded “super-profits.”

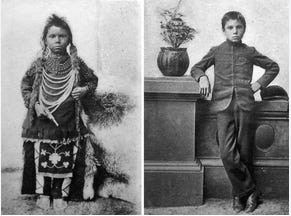

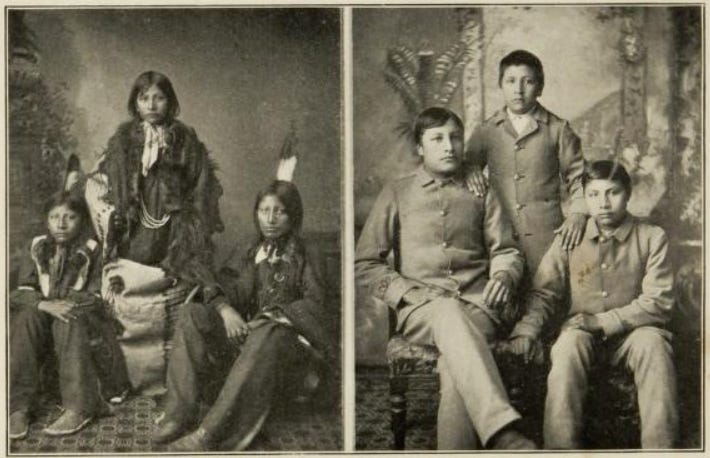

In the mother country, the employers could thus offer somewhat higher wages and better working conditions to their workers, and the state could start to provide modest social services. At least some of the proletarians in the mother lands thus became better off at the expense of the oppressed and exploited denizens of the colonies. In other words, the misery was exported from Europe to the colonies, to the unhappy lands that would later collectively be known as the “Third World.” (In the USA, the prosperity and freedom of the white population was similarly made possible by the exploitation and oppression of Afro-Americans and “Indians.”) In any event, under those conditions, most European socialists (or social-democrats) increasingly developed warm feelings towards a “fatherland” that treated them better, so they gradually abandoned their traditional Marxist internationalism to become rather nationalistic; discreetly, they – and their socialist (or social-democratic) parties – also ceased to believe in the inevitability and necessity of revolution and migrated from Marx’s revolutionary socialism to socialist “reformism.” This explains why, in 1914, most socialist parties would not oppose the war but would rally behind the flag to defend the fatherland that had presumably been so good to them. Third, territorial expansion also offered an advantage much appreciated by the many members of the elite who subscribed to Malthusianism, a trendy ideology at the time, which blamed overpopulation for the great social problems that ravaged all the industrialized countries. It made it possible to dump the restless and potentially revolutionary demographic surplus in distant lands such as Australia, where they could acquire land and start a farm, for example, by expelling or even exterminating the natives.

Projects for territorial acquisitions, undertaken under the auspices of a strong and even aggressive state, then, were favored by the aristocratic as well as the bourgeois factions of the elite. And they received considerable popular support, because they appealed to the romantic imagination and, more importantly, because even some of the proletarians could help themselves to the crumbs that fell off the table. The second half, and particularly the final quarter, of the nineteenth century thus witnessed a worldwide territorial expansion of European as well as two non-European industrial powers, the USA and Japan. However, the conquest of territories, where desiderata such as precious raw materials were to be found and where there existed plenty of investment opportunities, was rarely possible “next door.” The great exception to this general rule was provided by the USA, who grabbed the vast hunting grounds of the Native Americans, stretching all the way to the coast of the Pacific Ocean, and robbed neighboring Mexico of a huge part of its territory. It was generally more realistic, however, to dream of territorial acquisitions in faraway lands, above all in the “dark continent” that was to become the object of the famous “scramble for Africa.” Great Britain and France acquired vast territories, mostly in Africa but also in Asia. The USA expanded not only on its own continent but robbed Spain via a “splendid little war” of colonial possessions such as the Philippines, and Japan managed to turn Korea into a dependence. Germany, on the other hand, did not do very well, mostly because it remained focused for too long on the establishment of a unified state; as a latecomer in the scramble for colonies, it had to settle for relatively few and certainly less desirable possessions, such as “German Southwest Africa,” now Namibia. In any event, the industrial giants of Europe, plus the USA and Japan, without exception states organized according to capitalist principles, morphed at that time into “mother countries” or “metropoles” of vast empires. To this new manifestation of capitalism, originally a purely European phenomenon, that was henceforth spreading itself over the entire globe, a name was given in 1902 by a British economist, John A. Hobson: “imperialism.” In 1916, Lenin was to offer a Marxist view of imperialism in a famous pamphlet, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism.

Imperialism generated more and more tension and conflicts among the great powers that were competing to acquire control over as many economically important territories as possible. At that time, social Darwinism was a very influential scientific ideology, and it preached that competition was the basic principle of all forms of life. Not only individuals but also states had to compete mercilessly with each other in a struggle for survival. The strongest triumphed, and thus they became even stronger; the weak, on the other hand, were the losers, and they were left behind in the race for survival and were doomed to perish. To be able to compete with other states, a state had to be economically strong, and for that reason its “national economy” – that is, its corporations and banks – had to have control over as much territory as possible with raw materials, potential for the export of goods and investment capital, etc. Thus was generated a merciless worldwide scramble for colonies, even for lands one did not really need but did not want to fall into the hands of a competitor. Considering all this, the British historian Eric Hobsbawm drew the conclusion that capitalism’s trend towards imperialist expansion inevitably pushed the world in the direction of conflict and war.

Image: Head and shoulders portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II by Court Photographer T. H. Voigt of Frankfurt, 1902. (From the Public Domain)

However, in spite of tensions and crises, including a conflict about East African real estate that brought Britain and France to the brink of war in 1898, the Fashoda Crisis, Europe’s imperialist powers managed to acquire vast territories without fighting a major war against each other. By the turn of the century, the entire globe seemed to be partitioned.

According to historian Margaret MacMillan, this means that the imperialist powers no longer had any reason to quarrel, and she concludes that an accusing finger cannot be pointed at imperialism when the causes of the First World War are discussed. To this it can be replied – as the French historian Annie Lacroix-Riz has done – that there remained at least one “hungry” imperialist power which felt disadvantaged compared to “satisfied” powers such as Great Britain, was not prepared to put up with the status quo, aggressively pursued a redistribution of existing colonial possessions, and was in fact willing to wage war to achieve its objectives. That “hungry” power was Germany, which had belatedly developed an imperialist appetite, namely after Wilhelm II became emperor in 1888 and promptly demanded for the Reich a “place in the sun” of international imperialism, in other words, a redistribution of the colonial possessions that would provide Germany with a larger share. Colonial possessions, Lacroix-Riz points out, may have been distributed, but they could be redistributed. That redistributing the colonial possessions was possible, but also unlikely to be achieved peacefully, was demonstrated by the case of former Spanish colonies like the Philippines, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, which were transformed into satrapies of America’s “informal empire” as a result of the Spanish-American War of 1898.

Moreover, a considerable part of the world did in fact remain available for direct or indirect annexation as colonies or protectorates, or at least for economic penetration. MacMillan herself acknowledges that a “serious scramble for China,” similar to the earlier, risky race for territories in Africa, remained possible, the more so since not only the great European powers but also the USA and Japan displayed much interest in the land of unlimited possibilities that the Middle Empire seemed to be. The imperialist wolves were also keenly – and jealously – eying a couple of other major countries that had hitherto managed to remain independent, namely, Persia and the Ottoman Empire.

The competition between the imperialist powers was and remained very likely to lead to conflicts and wars, not only limited conflicts such as the Spanish-American War of 1899 and the Russian-Japanese War of 1905 but also a general conflagration involving most if not all powers. It almost came to such a conflagration in 1911 when, to the great chagrin of Germany, France turned Morocco into a protectorate. The case of Morocco shows how even supposedly satisfied imperialist powers such as France were never truly satisfied – just as immensely rich people never feel that they have enough riches – but continued to look for more ways to fatten their portfolio of colonial possessions, even if that threatened to cause a war.

Let us consider the case of the “hungry” imperialist power, Germany. The Reich, founded in 1871, had entered the scramble for colonies a little too late. It could actually consider itself lucky that it was still able to acquire a handful of colonies such as Namibia. But those hardly amounted to major prizes, certainly not in comparison to the Congo, a huge region bursting with rubber and copper that was pocketed by minuscule Belgium. With respect to access to sources of vital raw materials as well as opportunities for exporting finished products and investment capital, the tandem of Germany’s industry and finance thus found itself very much disadvantaged in comparison to its British and French rivals. Crucially important raw materials had to be purchased at comparatively high rates, which meant that the finished products of German industry were more expensive and therefore less competitive on international markets. This imbalance between extremely high industrial productivity and relatively restricted markets demanded a solution. In the eyes of numerous German industrialists, bankers, and other members of the country’s elite, the only genuine solution was a war that would give the German Empire what it felt entitled to and – to formulate it in Social-Darwinist terms – what it believed to be necessary for its survival: colonies overseas and, perhaps even more importantly, territories within Europe as well.

In the years leading up to 1914, the German Reich thus pursued an expansionist and aggressive foreign policy aimed at acquiring more possessions and turning Germany into a world power. This policy, of which Emperor Wilhelm II was the figurehead, has gone down in history under the label of Weltpolitik, “policy on a worldwide scale,” a term that was merely a euphemism for what was in fact an imperialist policy. In any event, Imanuel Geiss, an authority in the field of the history of Germany before and during the First World War, has emphasized that this policy was one of the factors “that made war inevitable.”

With respect to overseas possessions, Berlin dreamed of pinching the colonies of small states such as Belgium and Portugal. (And in Great Britain a faction within the elite, consisting mostly of industrialists and bankers with connections to Germany, was in fact willing to appease the Reich, not with a single square mile of their own Empire, of course, but with the gift of Belgian or Portuguese overseas possessions.) Nevertheless, it was above all within Europe itself that opportunities seemed to exist for Germany. Ukraine, for example, with its fertile farmland, loomed as the perfect “territorial complement” (Ergänzungsgebiet) for the highly industrialized German heartland; its bread and meat could provide cheap food for German workers, which would permit keeping their wages down. Likewise eyed by German imperialists was the Balkan, a region that might serve as source of cheap agricultural products and as market for German commodities. Germans in general were impressed with America’s conquest of the “Wild West” and Britain’s acquisition of the Indian subcontinent and dreamed that their country might similarly obtain a gigantic colony, namely by expanding into Eastern Europe in a modern-day edition of Germany’s medieval “push to the East,” the Drang nach Osten. The East would supply the Reich with abundant raw materials, agricultural products, and cheap labor in the shape of its numerous, supposedly inferior but muscular natives; and also a kind of social safety valve, because Germany’s own potentially troublesome demographic surplus could be shipped as “pioneers” to those distant lands. Hitler’s infamous fantasies with respect to “living space,” which he was to reveal in the 1920s in Mein Kampf and to put into practice during the Second World War, saw the light under those circumstances. In this respect, Hitler was not an anomaly at all, but a typical product of his time and space, and of the imperialism of that time and space.

Western Europe, more developed industrially and more densely populated than Europe’s east, was attractive to German imperialism as a market for the finished products of German industry, but also as a source of interesting raw materials. The influential leaders of the German steel industry did not hide their great interest in the French region around the towns of Briey and Longwy; that area – situated close to the border with Belgium and Luxembourg – featured rich deposits of high-quality iron ore. Without this ore, claimed some spokesmen of German industry, the German steel industry was condemned to death, at least in the long run. It was also believed that Germany’s Volkswirtschaft, its national economy, would profit greatly from the annexation of Belgium with its great seaport, Antwerp, its coal regions, etc. And together with Belgium its colony, the Congo, would of course also fall into German hands. Whether the acquisition of Belgium and perhaps even the Netherlands would involve direct annexation or a combination of formal political independence and economic dependence on Germany was a matter of debate among the experts within the German elite. In any event, in one way or another, virtually all of Europe was to be integrated into a “great economic space” under German control, The Reich would finally be able to take its rightful place next to Britain, the USA, etc. in the restricted circle of the great imperialist powers. (The historian Fritz Fischer has dealt with all this in his classical study of Germany’s objectives in World War I.)

It was obvious that Germany’s ambitions in the East could not be realized without serious conflict with Russia and the German aspirations with respect to the Balkans risked causing problems with Serbia. That country was already at loggerheads with the Reich’s biggest and best friend, Austria-Hungary, but it was supported by Russia. And the Russians were also very annoyed by Germany’s planned penetration of the Balkan Peninsula in the direction of Istanbul, since the straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean were at the very top of their own list of desiderata. St. Petersburg was almost certainly willing to go to war to deny Germany direct or indirect control of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles.

The German ambitions in Western Europe, and Belgium in particular, obviously ran counter to the interests of the British. At least as far back as the time of Napoleon, London had not wanted to see a major power ensconced in Antwerp and along the Belgian coast – and certainly not Germany, long a great power on land but now, with an increasingly impressive navy, also a menace at sea. With Antwerp, Germany would not only have at its disposal a “pistol aimed at England,” as Napoleon had described the city, but also one of the world’s greatest seaports. That would have made Germany’s international trade far less dependent on the services of British ports, sea lanes, and shipping, a major source of revenue of British commerce.

The real and imaginary interests and needs of Germany as a great industrial and imperialist power thus pushed the country increasingly rapidly, via an aggressive foreign policy, toward a war. But the possibility of war raised no great concerns within the elite of the military giant that Germany had already been for quite some time. To the contrary, among the industrialists, bankers, generals, politicians, and other members of the Reich’s establishment, only some rare birds did not wish for a war; most of them preferred a war as soon as possible, and many were even in favor of unleashing a preventive war. Of course, the German elite also featured less bellicose members, but among them, there prevailed the fatalist feeling that war was simply inevitable.

That the merciless competition between the great imperialist powers – a struggle of life and death, as seen from a social-Darwinist viewpoint – was virtually certain to lead to war, was also demonstrated by the case of Great Britain. That country marched into the twentieth century as the world’s superpower, in control of an unprecedented collection of colonial possessions. But the power and wealth of the Empire obviously depended on the fact that, thanks to the mighty Royal Navy, Britannia ruled the waves. And in that respect a very serious problem arose around the turn of the century. As fuel for ships, coal was quickly being replaced by petroleum on account of its far greater efficiency. Albion had plenty of coal but did not have petroleum, not even in its colonies, at least not in sufficient quantities. And so the search was on for plentiful and reliable sources of oil, the “black gold.” For the time being, that precious commodity had to be imported from what was then the world’s foremost producer and exporter, the USA. But that was not acceptable in the long run, since Britain often quarrelled with its former transatlantic colony about issues such as influence in South America, and the USA was also becoming a serious rival in the imperialist rat race.

Looking out for alternative sources, the British found a way to quench their thirst for petroleum, at least partly, in Persia. It was in this context that the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company was founded, later to be known as British Petroleum (BP). However, a definitive solution to the problem only appeared in sight when, still during the first decade of the twentieth century, significant deposits of oil were discovered in Mesopotamia, more specifically in the region around the city of Mosul. The patriciate ruling Albion – exemplified by gentlemen like Churchill – decided at that time that Mesopotamia, a hitherto unimportant corner of the Middle East destined to become Iraq after the First World War, but then still belonging to the Ottoman Empire, had to be brought under British control. That was not an unrealistic objective, since the Ottoman Empire was a large but weak country, from whose vast territory the British had already previously managed to carve attractive morsels, for example, Egypt and Cyprus. In fact, in 1899, the British had already snatched oil-rich Kuwait and proclaimed it a protectorate; they were to transform it in 1914 into a supposedly independent emirate. Possession of Mesopotamia, then, was seen to be the only way to make it possible for unlimited quantities of petroleum to flow unperturbed toward Albion’s shores.

However, in 1908, the Ottoman Empire became an ally of Germany, which meant that the planned acquisition of Mesopotamia was virtually certain to trigger war between Britain and the Reich. But the need for petroleum was such that plans were nonetheless made for military action. And these plans needed to be implemented as soon as possible. The Germans and Ottomans had started to construct the Bagdad Bahn, a railway that was to link Berlin via Istanbul with Baghdad, the Mesopotamian metropolis, situated close to Mosul, and that raised the prospect that barrels full of Mesopotamian oil might one day start to roll toward Germany for the benefit of the Reich’s growing collection of battleships, which happened to be the most dangerous rival of the Royal Navy! Since the Baghdad Bahn was expected to be completed in 1914, quite a few British political and military decision-makers were of the opinion that it was better not to wait very long before starting a war that appeared unavoidable in any event.

German Baghdad Railway. (From the Public Domain)

It was in this context that London’s traditional friendship with Germany came to an end, that Britain joined two former archenemies, France and Russia, in an alliance known as the Triple Entente, and that the British army commanders started to work out detailed plans for war against Germany in collaboration with their French counterparts. The idea was that the massive armies of the French and the Russians would smash Germany’s host, while the bulk of the Empire’s armed forces would invade Mesopotamia from India, beat the Ottomans, and grab the oil fields. The Royal Navy also promised to prevent the German Navy from attacking France via the English Channel, and on land, the French army was to benefit from (mostly symbolic) assistance by the relatively tiny British Expeditionary Corps (BEF). However, this Machiavellian arrangement was concocted in the greatest secrecy, and neither the Parliament nor the public were informed about it.

On the eve of the Great War, a compromise with the Germans remained possible and even enjoyed the favor of some factions within Britain’s political, industrial, and financial elite. A compromise would have provided Germany with at least a share of the Mesopotamian oil, but London sought to achieve nothing less than exclusive control over the “black gold” of Mesopotamia. The British plans to invade Mesopotamia were prepared as early as 1911 and called for the occupation of the strategically important city of Basra, to be followed by a march along the banks of the Tigris to Baghdad. Complemented by a simultaneous attack by British forces operating from Egypt, this invasion was to provide Britain with control over Mesopotamia and much of the rest of the Middle East. This scenario would indeed unfold during the Great War, but in slow motion, as it turned out to be a much tougher job than expected, and the objectives would only be achieved at the end of the conflict. Incidentally, the famous Lawrence of Arabia would not suddenly appear out of nowhere; he was merely one of the numerous Brits who, during the years leading up to 1914, had been carefully selected and trained to “defend” their country’s interests – mostly with respect to oil – in the Middle East.

The conquest of the oil fields of Mesopotamia constituted the prime objective of Britain’s entry into the war in 1914. When the war broke out, and the German and Austrian-Hungarian partners went to war against the Franco-Russian duo plus Serbia, there seemed to be no reason for Britain to become involved in the conflict. The government in London was confronted with a dilemma; it was honor-bound to keep the promises made to France but that would have revealed that these plans had been concocted in secret. However, Germany’s violation of Belgium’s neutrality provided London with the perfect pretext to go to war. In reality, the fate of the small country was of little or no concern to the British leaders, at least as long as the Germans did not proceed to grab Antwerp. Neither was the violation of a country’s neutrality deemed to be a big deal; during the war, the British themselves would not hesitate to violate the neutrality of a number of countries, namely, China, Greece, and Persia.

Like all plans made in preparation for what was to become the “Great War,” the scenario concocted in London failed to unfold as anticipated. The French and Russians did not manage to crush the Teutonic host, so the British had to send many more troops to the continent – and suffer much greater losses – than foreseen. And in the distant Middle East, the Ottoman army – expertly assisted by German officers – unexpectedly proved to be a tough nut to crack. In spite of these inconveniences, which caused the death of about three quarters of a million soldiers in the UK alone, all was well in the end; in 1918, the Union Jack fluttered over the oil fields of Mesopotamia.

This short survey demonstrates that, as far as the rulers of Britain were concerned, World War I was not fought to save “gallant little Belgium” or to champion the cause of international law and justice. At stake were economic interests, the interests of British imperialism, which happen to be the interests of the rich and powerful British aristocratic gentlemen and bourgeois burghers whose corporations and banks lusted for raw materials such as petroleum – and for much else.

It is also obvious that for the patricians in power in London, the war was not a war for democracy at all. In the conquered Middle East, the British did nothing to promote the cause of democracy, to the contrary. Britain’s imperialist interests were better served by subtle and not-so-subtle un- and even anti-democratic arrangements. Occupied Palestine was ruled by them in approximately the same way that occupied Belgium had been ruled by the Germans. And in Arabia, London’s actions only took into account its own interests – as well as the interests of a handful of indigenous families that were considered to be useful partners. The vast homeland of the Arabs was parcelled out and distributed to those partners, who proceeded to establish states they could rule as if they were personal property. And when many denizens of Mesopotamia had the nerve to resist their new British bosses, Churchill ordered bombs to rain down on their villages, including bombs with poison gas.

On the eve of the outbreak of the Great War, in all the imperialist countries there were countless industrialists and bankers who favored a “bellicose economic expansionism.” Nevertheless, many capitalists – and possibly even a majority – appreciated the advantages of peace and the inconveniences of war and were therefore not warmongers at all, as Eric Hobsbawm has emphasized. But this observation has wrongly caused the conservative British historian Niall Ferguson to jump to the conclusion that the interests of capitalists did not play a role in the eruption of the Great War in 1914. For one thing, countless industrialists and bankers and member of the upper-middle class displayed an ambivalent attitude with respect to war. On the one hand, even the most bellicose among them realized that a war would have most unpleasant aspects, and for that reason, they preferred to avoid war. However, as members of the elite, they also had reason to believe that the unpleasantness would be experienced mostly by others – and of course mostly by the simple soldiers, workers, peasants, and other plebeians to whom the nasty jobs of killing and dying were traditionally entrusted.

Moreover, the assumption that peace-loving capitalists did not want war reflects a binary, black-and-white kind of thinking, namely that peace was the alternative to war and vice-versa. However, reality has a way of being more complex. There was in fact another alternative to peace, namely revolution. And that other alternative to peace was far more repulsive than war to most if not all capitalists and other bourgeois and aristocratic members of the elite. The aristocracy and the bourgeoisie had been obsessed with fear of revolution ever since the events of 1848 and 1871 had revealed the revolutionary intentions and potential of the proletariat. Afterwards, working-class parties subscribing to Marx’s revolutionary socialism had been founded, had become increasingly popular, and remained officially committed to overthrow the established political and social-economic order via revolution even though, as we have seen, they had in fact discreetly become reformist. The decade before the outbreak of war, finally, ironically called Belle Époque, witnessed not only new revolutions (in Russia, in 1905 and in China, in 1911) but also, throughout Europe, a never-ending series of strikes, demonstrations, and riots that seemed to be harbingers of revolution in the very heartland of imperialism. In this context, war was promoted not only by philosophers such as Nietzsche and other intellectuals, by military and political leaders, but also by leading industrialists and bankers as an effective antidote to revolution.

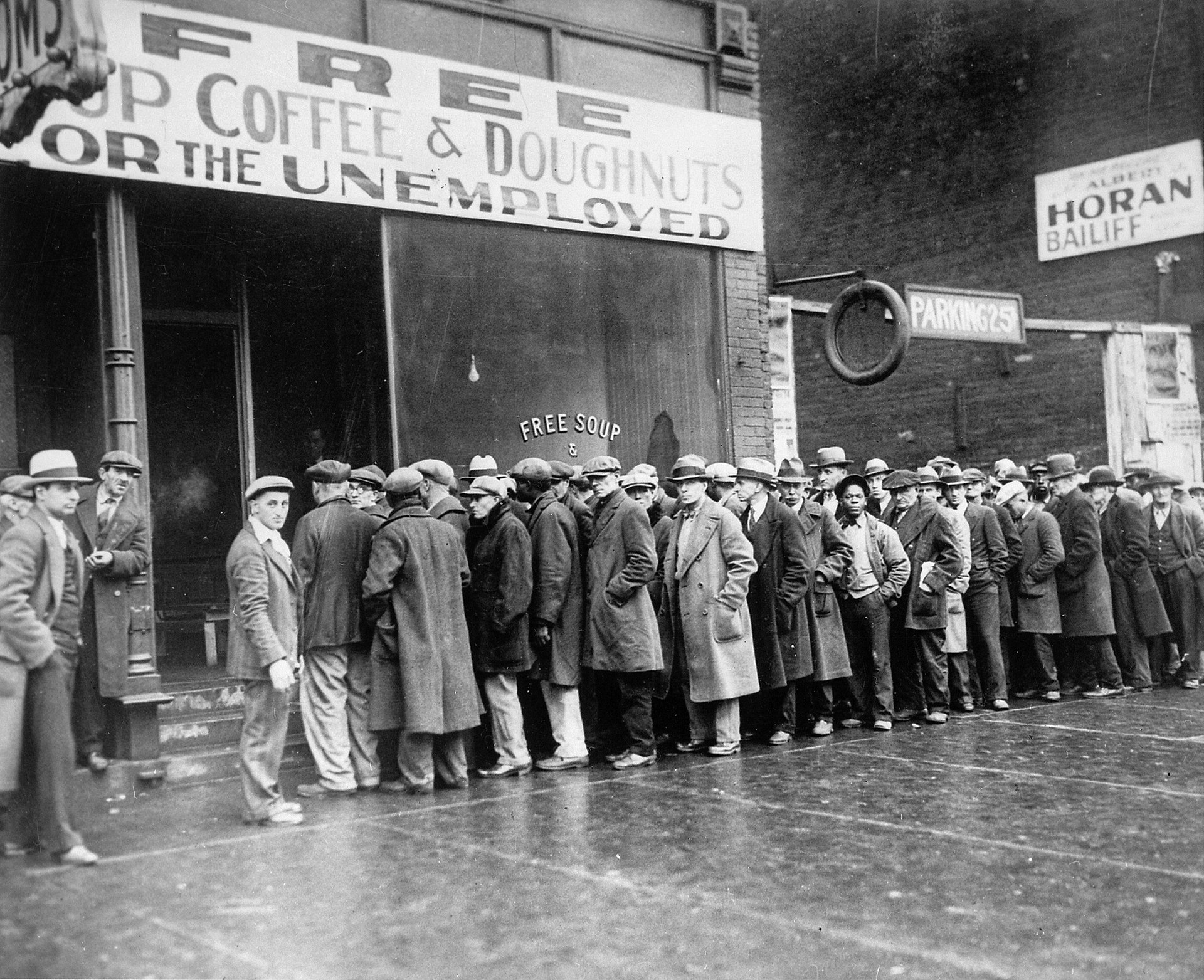

During the years leading up to 1914, countless members of the bourgeoisie (and the aristocracy) thus imagined themselves to be witnessing a race between war and revolution, a sprint whose outcome could be decided at any time. Which one of the two was going to win? The burghers, fearing revolution, prayed that war would be the winner. With revolution, rather than peace, as the most likely alternative to war, even the most peace-loving capitalists definitely preferred war. And since they were afraid that revolution might win the race, that is, might break out before war, the capitalists, and the bourgeois and aristocratic members of the elite in general, actually hoped for war to come as soon as possible, which is why they experienced the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914 as a deliverance from unbearable uncertainty and tension. This relief was reflected by the fact that the famous pictures of folks enthusiastically celebrating the declaration of war, taken mostly in the “better” districts of the capitals, almost exclusively featured well-dressed ladies and gentlemen, and not workers or peasants, who are known to have been mostly depressed by the news.

In its imperialist manifestation, capitalism was definitely responsible for the many colonial wars that had been waged and was also responsible for the Great War that broke out in 1914. Countless contemporaries realized this only too well. As the great French socialist leader Jean Jaurès already declared in 1895, “capitalism carries war within itself just like the thundercloud carries the storm.” Jaurès was a convinced anticapitalist, of course, but many members of the bourgeois and aristocratic elite were also keenly aware of the link between war and their economic interests, and occasionally acknowledged this. General Haig, for example, who would command the British Army from 1915 until the end of the war, declared on one occasion that he was not “ashamed of the wars fought to open up the markets of the world to our traders.” It was the fateful emergence of the imperialist version of capitalism, then, that, to use Eric Hobsbawm’s words, “pushed the world to conflict and war.” In comparison, the fact that numerous individuals among the industrialists and bankers may privately have cherished peace is of little or no importance and certainly does not permit the conclusion that capitalism did not lead to the Great War. It would be equally fallacious to conclude that Nazism was not really anti-Semitic and did not play a role in the origins of the Holocaust, because quite a few individual Nazis were personally not anti-Semitic.

It is also because imperialist aspirations were responsible for it, that the war that broke out in 1914, essentially a European conflict, developed into a world war. We should not forget that there was fighting not only in Europa but also in Asia and Africa. While the great powers would fight each other primarily, and most “visibly,” in Europe, their armies would also do battle in each other’s colonial possessions in Africa, in the Middle East, and even in China. Finally, in Versailles, the victors would divide and claim not only the relatively modest booty represented by Germany’s former colonies but especially the petroleum-rich regions of the Middle East that had belonged to the Ottoman Empire.

Japanese troops landing near Qingdao (From the Public Domain)

Let us take a quick look at the role played by Japan in the Great War. With its victory over Russia in 1905, the “land of the rising sun” revealed itself to be the only “non-Western” member of the restricted club of imperialism’s great powers. Like all other imperialist powers, Japan was henceforth keen to acquire additional lands as colonies or protectorates in order to make raw materials and such available to its industry, thus making it stronger vis-a-vis the competition – for example, from the USA. The war that broke out in Europe in 1914 provided Japan with a golden opportunity in this respect. On September 23 of that year, Tokyo declared war on Germany for the simple reason that this made it possible to conquer the Reich’s mini-colony (or “concession”) in China, the Bay of Kiao-Chau (or Kiao-Chao), as well as its island colonies in the Northern Pacific. In the case of Japan, it is obvious that the country went to war in order to achieve imperialist objectives. In the case of the Western imperialist powers, however, we continue to be told that in 1914, arms were taken up solely to defend liberty and democracy.

The Great War was a product of imperialism. Its focus was therefore on profits for the big corporations and banks under whose auspices imperialism had developed and whose interests imperialism purported to serve. In this respect, the war did not disappoint. It was admittedly a catastrophe for millions of human beings, for the plebeian masses, for whom it offered nothing but death and misery. But for the industrialists and bankers of each belligerent country – and quite a few neutral countries, such as the USA before 1917 – it revealed itself as a cornucopia of orders and profits.

The conflict of 1914–1918 was an industrial contest in which modern weapons such as cannon, machine guns, poison gas, flamethrowers, tanks, airplanes, barbed wire, and submarines were decisive. This materiel was mass produced in the factories of the industrialists, yielding gargantuan profits, profits that were taxed only minimally in most countries. Profitability was also maximized by the fact that in all belligerent countries the wages (but not the prices) were lowered, while the working hours were lengthened and strikes were forbidden. (That was possible because, as we have seen earlier, imperialism had integrated the leaders and the rank-and-file of the supposedly internationalist and revolutionary socialist parties – and labor unions – into the established order and turned them into patriots, who in 1914 revealed themselves ready to rush to the defense of the fatherland and make the sacrifices presumably required to ensure its victory.) The most famous of the arms manufacturers to be blessed with war profits was Krupp, the world-famous German producer of cannon. But in France too, “merchants of death” did a wonderful business, for example, Monsieur Schneider, known as the French Krupp, who in 1914–1918 enjoyed “a veritable explosion of profits,” and Hotchkiss, the great specialist in the production of machine guns. State orders for war materiel signified huge profits not only for corporations but also for the banks that were asked to loan the huge sums of money needed by governments to finance these purchases and the costs of the war in general. In the USA, J.P. Morgan & Co, also known as the “House of Morgan,” was the undisputed champion glutton in this field. Morgan not only charged high interest rates on loans to the British and their allies but also earned fat commissions on sales to Britain by American firms that belonged to its “circle of friends,” such as Du Pont and Remington.

In the spring of 1917, after a revolution had broken out in Russia and the French ally was rocked by mutinies in its army, it was feared that the British might lose the war and therefore not be able to pay back their war debts. It was in this context that the Wall Street lobby, headed by Morgan, successfully pressured President Wilson to declare war on Germany, thus enabling Albion to ultimately win the war and avoid a catastrophe for the US banks, especially Morgan. This development likewise illustrates the fact that the First World War was primarily determined by economic factors, that it was the fruit of imperialism, a system that purported to serve the profit-maximizing interests of corporations and banks – and did.

With respect to the entry of the USA into the great clash of imperialisms of 1914–1918, another remark is in order. It was clear that the imperialist powers that would exit the war triumphantly would pocket great imperialist prizes, and that the losers would have to cough up some of their imperialist assets. And what about the neutrals? In January 1917, the French Prime Minister, Aristide Briand, publicly gave the answer, obviously anticipating a victory for the Triple Entente; neutral countries would not be invited to the peace conference and would not receive a share of the loot, that is, of goodies such as German colonies, the oil-rich regions of the doomed Ottoman Empire, and concessions and lucrative business opportunities in China. In this respect, Japan, America’s great competitor in the Far East, had already made a move in 1914 by declaring war on Germany and pocketing the Reich’s concession in China. In the USA, this conjured up the risk that Japan might end up monopolizing China economically, excluding American business. It is extremely likely that Washington took Briand’s hint and that this consideration also influenced the decision, taken in April of 1917, to declare war on Germany. In the 1930s, an inquiry by the Nye Committee of the American Congress was to come to the conclusion that the country’s entry into the war had indeed been motivated by the wish to be present when, after the war, the moment would come “to redivide the spoils of empire.”

The war provided a mighty stimulus for the maximization of profits made by corporations and banks. But was that not one of the reasons why they had looked forward to war? (Another reason was of course the elimination of the revolutionary threat.) But the conflict also yielded them other considerable benefits. In all belligerent countries, the war reinforced the trend toward gigantism, that is, the ongoing emergence of a relatively small elite of very big corporations and banks. This was so because only big firms could benefit from the state orders for weapons and other war materiel. Conversely, small producers did not profit from the war. Many of them lost their personnel, their suppliers, or their customers; their profits declined, and many of them disappeared from the scene, never to return. In this sense, it is true what Niall Ferguson has pointed out, that during the Great War, the average profits of businesses were not very high; however, the profits of the big firms and banks, the capitalist big boys who dominated the economy since the emergence of imperialism were in fact considerable, as Ferguson himself acknowledges.

Class conflict is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon, as Domenico Losurdo has emphasized in a book on that topic. It is not merely a bilateral conflict between capital and labor but also reflects contradictions between bourgeoisie and nobility, between industrialists of different countries, between the colonies and their mother countries, and also between factions within the bourgeoisie. An example of the latter is the conflict between big and small producers, big business and little business, the upper-middle class or haute bourgeoisie, and the lower-middle class or petite bourgeoisie. Imperialism was – and continues to be – the capitalism of the big boys, the corporations and big banks, and it was imperialism that gave birth to the Great War. It is no coincidence that this big war also favored the big capitalists in their struggle against the little capitalists.

The Great War also privileged the upper-middle class, the gentlemen of industry and finance, vis-a-vis their partner within the elite, the landowning nobility. The nobility had also wanted war, because it expected many advantages from it. But the conflict revealed itself as something very different from the old-fashioned kind of warfare they had expected, in which their beloved cavalry and traditional weapons such as swords and lances would be decisive but, as Peter Englund has written, “an economic competition, a war between factories.” The Great War was an industrial war, fought with modern weapons mass-produced in the factories of the bourgeois industrialists, and in the course of the war, representatives of corporations and banks – such as Walter Rathenau in Germany – played an increasingly important role as “experts” within governments and state bureaucracies. The bourgeoisie thus managed to increase not only its wealth but also its power and prestige – very much to the disadvantage of the aristocrats, whose weapons and expertise proved useless for the purpose of twentieth-century warfare. Until 1914, the haute bourgeoisie had been the junior partner of the nobility within the elite in most countries but that changed during the war and because of the war. After 1918, within the elite, the industrial and financial haute bourgeoisie was on top, with the nobility as its sidekick.

The Great War was very much determined by economic factors, and it was the product of the merciless competition among the imperialist powers, a competition about territories with considerable natural and human resources. It is therefore only logical that this conflict was eventually decided by economic factors; the imperialist powers that emerged as victors in 1918 were those who already controlled the greatest colonial and other territorial riches when the war started in 1914 and were therefore abundantly blessed with strategic raw materials, especially rubber and petroleum, needed to win a modern, industrial war. Let us examine this issue in greater detail.

In 1918, Germany managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, so to speak, because in the spring and summer of that year, the Reich had actually come tantalizingly close to achieving victory. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed with revolutionary Russia on March 3, 1918, had enabled the Reich’s army commanders, led by General Ludendorff, to transfer troops from the eastern to the western front and launch a major offensive there on March 21. Considerable progress was achieved at first, but the Allies succeeded time and again to bring in the reserves of men and materiel needed to plug the gaps in their defensive lines, slow down the German juggernaut’s advance, and finally to arrest it. August 8 was the date when the tide turned. On that day, the Germans were forced onto the defensive and had to withdraw systematically until they finally capitulated on November 11. The allied triumph was made possible by the fact that they – and especially the French – disposed of thousands of trucks to quickly transport large numbers of soldiers to wherever they were needed. The Germans, on the other hand, still moved their troops mostly by train, as in 1914, but crucial sectors of the front were hard to reach that way. The superior mobility of the Allies was decisive. Ludendorff was to declare later that the triumph of his adversaries in 1918 amounted to a victory of French trucks over German trains.

However, this triumph can also be similarly described as a victory of the rubber tires of the Allies’ vehicles, produced by firms such as Michelin and Dunlop, over the steel wheels of German trains, produced by Krupp. Thus it can also be said that the victory of the Entente against the Central Powers was a victory of the economic system, and particularly the industry, of the Allies, against the economic system of Germany and Austria-Hungary, an economic system that found itself starved of crucially important raw materials because of the British blockade. “The military and political defeat of Germany,” writes the French historian Frédéric Rousseau, “was inseparable from its economic failure.” But the economic superiority of the Allies clearly has a lot to do with the fact that the British and French – and even the Belgians and Italians – had colonies where they could fetch whatever was needed to win a modern, industrial war, especially rubber, oil, and other “strategic” raw materials – plus plenty of colonial laborers to repair and even construct the roads along which trucks transported allied soldiers.

Rubber was not the only strategic type of raw material that the Allies had in abundance while the Germans lacked it. Another one was petroleum, for which the increasingly motorized land armies – and rapidly expanding air forces – were developing a gargantuan appetite. During a victory dinner on November 21, 1918, the British minister of foreign affairs, Lord Curzon, was to declare, not without reason, that “the allied cause floated to victory upon a wave of oil,” and a French senator proclaimed that “oil had been the blood of victory.” A considerable quantity of this oil had come from the USA. It was supplied by Standard Oil, a firm belonging to the Rockefellers, who made a lot of money in this type of business, just as Renault did by producing the gas-guzzling trucks. It was only logical that the Allies, swimming in petroleum, had acquired all sort of modern, motorized, gas-guzzling equipment. In 1918, the French not only had huge quantities of trucks but also a major fleet of airplanes. And in the war’s final year, the French as well as the British also disposed of cars equipped with machine guns or cannon and above all of large numbers of tanks. If the Germans had no significant quantities of trucks or tanks, it was also because they lacked petroleum; only insufficient amounts of Rumanian oil were available to them.

The Great War happened to be a war between imperialist rivals, in which the great prizes to be won were territories bursting with raw materials and cheap labor, the kind of things that benefited a country’s “national economy,” more specifically its industry, and thus made that country more powerful and more competitive. It is therefore hardly a coincidence that the war was ultimately won by the countries that had been most richly endowed in this respect, namely the great industrial powers with the most colonies. In other words: that the biggest imperialisms – those of the British, the French, and the Americans – defeated a competing imperialism, that of Germany, admittedly an industrial superpower, but underprivileged with respect to colonial possessions. In view of this, it is even amazing that it took four long years before Germany’s defeat was a fait accompli. On the other hand, it is also obvious that the advantages of having colonies and therefore access to unlimited supplies of food for soldiers and civilians as well as rubber, petroleum, and similar raw materials, as well as a virtually inexhaustible reserve labor force, were only able to reveal themselves in the long run. The main reason for this is that in 1914, the war started as a continental kind of Napoleonic campaign that was to morph – imperceptibly, but inexorably – into a worldwide contest of industrial titans. In 1914, Germany, a military superpower, still stood a chance to win the war, especially since it had excellent railways to ferry its armies to the western and eastern fronts – and more than enough of the coal needed as fuel for the steam trains. This is how a big victory was achieved against the Russians at Tannenberg. However, after four long years of modern, industrial, and in many ways “total” war, economic factors revealed themselves as decisive. By the time Ludendorff launched his spring-offensive in 1918, the prospects for a final victory had long gone up in smoke for a German Reich that was prevented by a Royal Navy blockade from reaching territories where it might have been able to fetch adequate amounts of the collective sine qua non of victory in a modern war – strategic raw materials such as petroleum, food for civilians as well as soldiers, cheap labor for industry and agriculture, and so forth.

The Great War of 1914–1918 was a conflict in which two blocks of imperialist powers fought each other for the possession of lands in Europe itself, Africa, Asia, and the entire world. The result of this titanic struggle was a victory for the Anglo-French duo, a major defeat for Germany, and the inglorious demise of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. In reality, the outcome of the war was unclear, confusing, and unlikely to please anybody. Great Britain and France were the victors but were exhausted by the enormous demographic, material, financial, and other sacrifices they had had to bring; they were no longer the superpowers they had been in 1914. Germany had likewise paid a heavy price, found itself punished and humiliated at Versailles, and lost not only its colonies but even a large part of its own territory; the country was allowed to have only a tiny army, but it remained an industrial superpower that was likely to try once again to achieve great imperialist objectives, as in 1914. Moreover, the war had been an opportunity for two non-European imperialisms to reveal their ambitions, namely, Japan and the USA. The struggle for supremacy among imperialist powers, which is what 1914–1918 had been, thus remained undecided. To make the situation even more complex, along with Austria-Hungary yet another major imperialist actor had departed from the scene, though in a very different way. Russia had morphed, via a great revolution, into the Soviet-Union. That resolutely anti-capitalist state revealed itself to be a thorn in the imperialist side, because it functioned not only as source of inspiration for revolutionaries within each imperialist country but also encouraged anti-imperialist movements in the colonies. Under these circumstances, Europe and the entire world continued to experience great tensions and conflicts that were to yield a second world war or, as many historians now see it, the second act of the great “Thirty Years’ War of the 20th Century.”

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Jacques R. Pauwels was born in Belgium in 1946, moved to Canada in 1969. Undergraduate history studies at Ghent University, Phd in history from York University in Toronto; MA and PhD in Political Science from University of Toronto. Part-time lecturer in history at various universities in Ontario from approximately 1975 to 2005.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Cross-References

- German Imperialism and Social Imperialism (1871–1933)

- United States, Imperialism in the Western Hemisphere

- United States, Imperialism, 19th century

Sources

Englund, P. (2012). The beauty and the sorrow: An intimate history of the first world war. London: Vintage.

Ferguson, N. (1999). The pity of war. New York: Basic Books.

Fischer, F. (1967). Germany’s aims in the first world war. New York: W. W. Norton.

Geiss, I. (1972). Origins of the first world war. In H. W. Koch (Ed.), The origins of the first world war: Great power rivalry and German war aims (pp. 36–78). London/Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Hobsbawm, E. (1994). The age of empire 1875–1914. London: Abacus. (Original edition: 1987).

Lacroix-Riz, A. (2014). Aux origines du carcan européen (1900–1960): La France sous influence allemande et américaine. Paris: Delga.

Lenin [Vladimir Ulyanov]. (1963). Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism (new ed.). Moscow: Progress Publishers. (Original edition: 1916). http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc.

Losurdo, D. (2013). La lotta di classe: Una storia politica e filosofica. Bari: Laterza.

MacMillan, M. (2013). The war that ended peace: The road to 1914. Toronto: Allen Lane.

Pauwels, J. R. (2016). The great class war 1914–1918. Toronto: James Lorimer.

Rousseau, F. (2006). La Grande Guerre en tant qu’expériences sociales. Paris: Ellipses Marketing.

Featured image: Vimy Ridge, April 1917–First World War–Photograph taken during Battle of Vimy Ridge. A large Naval gun. April, 1917. (CP PHOTO) 1999 (National Archives of Canada) PA-001187

Below are the author’s books:

Dimitri began his legal career at the Wall Street law firm of

Dimitri began his legal career at the Wall Street law firm of

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

The Worldwide QR Verification Code project lays the groundwork for the instatement of a “Digitized Global Police State” controlled by the financial establishment. It’s part of what the late David Rockefeller entitled “The March towards World Government” based on an alliance of bankers and intellectuals (See

The Worldwide QR Verification Code project lays the groundwork for the instatement of a “Digitized Global Police State” controlled by the financial establishment. It’s part of what the late David Rockefeller entitled “The March towards World Government” based on an alliance of bankers and intellectuals (See

Flashback to April 25, 2009: the World Health Organization (WHO) headed by

Flashback to April 25, 2009: the World Health Organization (WHO) headed by