First published on September 15, 2014

World War II demonstrated an enormous shift in the technological capability of the United States to bring death and destruction to the civilian populations of its enemies through aerial attack. The American air forces undertook strategic bombing campaigns that pulverized and burned numerous German and Japanese cities, culminating in the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This bombing killed hundreds of thousands of civilians.

Although the massive killing of noncombatants did not provoke widespread protests or recriminations among Americans at the time, the aftermath was not a simple story of acceptance of the practice as a common and legitimate method of warfare in a new technological age of air power. The experience of the Korean War demonstrated that American moral scruples against targeting civilians did not disappear with the bombing in World War II, as some historians have argued.1 Instead, American norms about bombing civilians followed a more complicated evolution.

Only five years later, the Korean War followed the pattern set by World War II of massive civilian destruction inflicted by bombing. Nevertheless, American leaders continued to claim throughout the war that U.S. air power was being used in a discriminate manner and was avoiding harm to civilians, as they had asserted even during the height of the bombing in World War II. The elasticity of the definition of a “military target” helped make these claims of discrimination more plausible.

The new bombing capabilities contributed to stretching the definitions of military targets because they brought new portions of civilian societies, such as transportation networks, arms factories, and their workers, within reach and under consideration for targeting. However, the American experience during the Korean War suggests that a dynamic of escalation stretched definitions of “military targets” even more. As military crises threatened and the war dragged on, American commanders vastly expanded the portion of the enemy’s society deemed to be a “military target.” While the loose semantics of military targets made it easier to claim publicly that prohibitions on targeting civilians remained, the prohibition found active reinforcement in the United States’ prominent role in the post-World War II war crimes trials of Germans and Japanese. Having held their former enemies accountable for harming civilians, Americans worked to distance themselves from similar practices, and the international competition of the Cold War only increased the stakes for American identity and political interests. In short, the broadly accepted moral prohibition against targeting civilians did not disappear with the bombing in World War II and Korea.

Although the norm against targeting civilians remained robust in the face of the technological transformations surrounding air power, the new bombing capabilities did foster several related changes in thinking about war’s harm to civilians and in international humanitarian law. One of the most significant was the increased importance of intention in rationalizing harm to noncombatants. For Americans, the crucial dividing line between justifiable and unjustifiable violence increasingly became whether their armed forces intentionally harmed civilians. With this reasoning, unintended harm—what later would be called “collateral damage”—became a tragic but acceptable cost of war.

The difficulties of controlling the violence of air power made common and widespread unintended harm plausible. American weapons might inflict massive casualties on civilians, as they had in World War II and Korea, but only intentionally targeting civilians remained a crime. International humanitarian law lagged behind the development of public norms on bombing but did eventually formally incorporate restrictions on bombing and in particular reflected this growing emphasis on intention. While other changes in thinking about bombing civilians are more difficult to assess because of the changing nature of American wars after Korea, and limited access to sources related to more recent conflicts, Americans did come to accept that certain portions of civilian society that directly supported the fighting capabilities of armed forces, such as arms factories and their workers, were justifiable targets for attack although destroying cities as such remained controversial.

THE WORLD WAR II BACKGROUND

On the eve of World War II, American leaders strongly condemned the bombing of civilians. Following Japanese air strikes in China and fascist bombing in Spain, the U.S. Senate issued its own “unqualified condemnation of the inhuman bombing of civilian populations” in 1938. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt urgently appealed to all sides in the hostilities to affirm publicly that their armed forces “shall in no event, and under no circumstances, undertake the bombardment from the air of civilian populations or of unfortified cities.” Alluding to earlier air attacks, he said “ruthless bombing” had killed and maimed thousands of defenseless men, women, and children and had “profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity.” Roosevelt feared that hundreds of thousands of “innocent human beings” would be harmed if the belligerent nations sunk to “this form of inhuman barbarism.”2 As the fighting in Europe escalated, the American press contained regular discussion of the bombing of civilians by both the Germans and the British.3 These public expressions of concern suggested that Americans supported a transnational norm against attacks on civilians, from bombing or otherwise, or that, at least, American leaders and journalists thought this norm had widespread support. World War II offered further evidence of this norm’s existence.

Indeed, judged from the perspective of what American leaders said about the bombing of civilians, little changed during World War II, even at the height of the air campaigns against Germany and Japan. They continued to talk as if they were trying to uphold the prohibition against targeting civilians, even though the reality of civilian deaths strained the credibility of their claims. U.S. armed forces described their strategic bombing methods as precision bombing throughout the war.4 When American planes joined the British Royal Air Force in burning Dresden in February 1945, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson assured the public: “We will continue to bomb military targets and . . . there has been no change in the policy against conducting ‘terror bombings’ against civilian populations.” When asked off the record about the burning of Tokyo at a press conference, an Air Force spokesman General Lauris Norstad denied that there had been any change in the Air Force’s basic policy of “pin-point” precision bombing.5 President Harry S. Truman in his initial public statements even described the attack on Hiroshima as a strike against “a Japanese Army base” and said that “we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.”6

So even in the face of these gross violations of the custom of actually sparing civilians, American leaders persisted in publicly deferring to a norm against targeting civilians by justifying the bombing as attacks on military targets and rarely claiming that attacking civilians directly was legitimate. There is still much work to be done to answer the question of whether these statements by American leaders reflected wider public sentiments, or political calculation. A better assessment of the breadth and depth of the American public’s attachment to the norm against attacking civilians during World War II is also needed. After all, American reactions to the bombing of civilians seem to have been quite muted during the war, and little protest against the bombing occurred.7 However, several factors could help explain why this apparent quiescence was not proof of Americans abandoning the norm against targeting civilians in war. One was the relative novelty of the extensive killing of civilians through bombing, and the limited information that Americans had about the attacks during the war, especially when official sources were continuing to claim that air power was being used precisely. Another could have been beliefs that the violence in World War II was exceptional even for war, justified as retribution for German or Japanese aggression and atrocities, or because such tactics were a lesser evil than the feared consequences of defeat by the Axis powers.

Although Americans were quiet about the harm to civilians resulting from U.S. bombing, they spoke out loudly against German and Japanese atrocities. Condemnation and prosecution of Axis atrocities after World War II provided the strongest reinforcement of the norm against attacking civilians. The Nuremberg tribunals in Germany and a similar set of war crimes trials of the Japanese focused international attention on the harm that Axis leaders and soldiers had inflicted on civilians and held them criminally accountable for it. This assertive application of international law and the leading role that the United States played in these prosecutions reinforced the impression that Americans remained committed to the norm against attacking civilians. However, conscious of the snares of hypocrisy, none of the tribunals prosecuted any of the defendants for promiscuous bombing of civilians. As U.S. relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated, Americans increasingly sought to distinguish clearly American killing of civilians in the past war and their strategies for fighting future wars in an atomic age from the crimes of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. In clashes with the United States, the Soviet Union enthusiastically condemned the American armed forces for relying on barbarous methods of bombing civilians to fight imperialistic wars.8

While the war crimes trials and the Cold War helped to reaffirm the norm against targeting civilians, American postwar discussion of air power did not clearly reflect this at first. Enthusiastic embrace of the American atomic monopoly and awe over the power of nuclear weapons combined with the popularity of the U.S. Air Force to produce much loose talk about bombing cities and civilians in future wars. For four years after World War II, it was difficult to tell from what Americans said publicly that they had not abandoned the custom of sparing civilians in war.9 However, a strand of criticism of strategic bombing was growing as well, and it emerged as a national issue in 1949 when U.S. Navy admirals attacked their Air Force colleagues in a dramatic set of Congressional hearings. During this “Revolt of the Admirals” as the media came to call it, a string of admirals deployed arguments that appealed to the norm against targeting civilians in raising their concerns over military policy and the defense budget. At the hearings, Rear Admiral Ralph A. Ofstie contended that “strategic air warfare, as practiced in the past and as proposed for the future, is militarily unsound and of limited effect, is morally wrong, and is decidedly harmful to the stability of a postwar world.” These charges prompted the Air Force to clarify its stance on bombing civilians. The Secretary of the Air Force W. Stuart Symington said bluntly: “It has been stated that the Air Force favors mass bombing of civilians. That is not true. It is inevitable that attacks on industrial targets will kill civilians. That is not an exclusive characteristic of the atomic bomb, but is an unavoidable result of modern total warfare.” 10 Symington distinguished between targeting industry which unavoidably killed civilians, and targeting civilians generally and directly. When confronted starkly with the idea of accepting the targeting of civilians as a legitimate method of war, the Air Force and almost every participate in the 1949 hearings avoided such a course.

THE KOREAN WAR

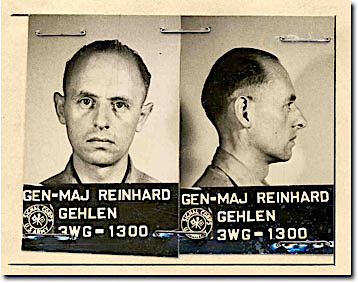

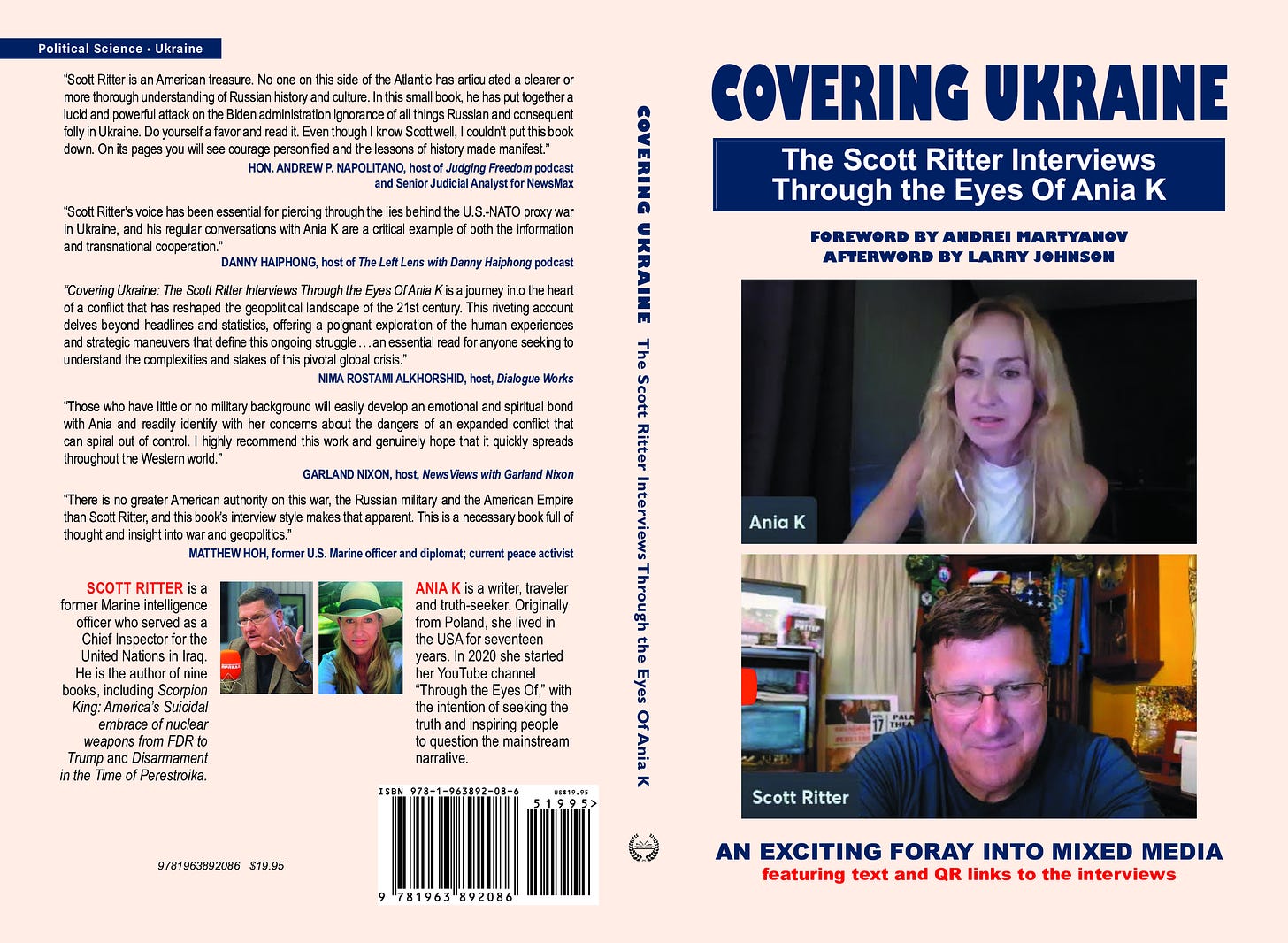

General MacArthur discusses the military situation with Ambassador John J. Muccio at ROK Army headquarters, 29 June 1950.

(National Archives”)

General MacArthur discusses the military situation with Ambassador John J. Muccio at ROK Army headquarters, 29 June 1950.

(National Archives”)

When the United States intervened in the war on the Korean peninsula in 1950, Americans continued to proclaim a norm against targeting civilians, even though, like World War II, the Korean War would become massively destructive of civilian lives and property. However, the devastation did not come immediately. American leaders explicitly rejected the fire-bombing of North Korean cities in the early days of the war. The Korean War would not begin as World War II had ended. The experiences of 1945 had not made the obliteration of cities and their populations the standard tactic for U.S. air power, only one of a range of options. Firebombing and the widespread harm to Korean civilians would only come after a process of escalation and dramatic setbacks for United Nations forces in the fall of 1950.

Only days after the outbreak of heavy fighting in Korea on June 25, 1950, President Truman ordered U.S. air attacks against North Korea in support of the American led intervention by the United Nations. The instructions from Washington for the U.N. commander General Douglas A. MacArthur specified a narrow range of targets for attack. The message from the Joint Chiefs of Staff read: “You are authorized to extend your operations into Northern Korea against air bases, depots, tank farms, troop columns and other such purely military targets, if and when, in your judgment, this becomes essential for the performance of your missions…or to avoid unnecessary casualties to our forces.” The orders also directed operations in North Korea to “stay well clear of the frontiers of Manchuria or the Soviet Union.”11 MacArthur’s instructions urged discrimination and limitations. Clearly, the new capacity to destroy entire cities from the air had not obliterated the distinction between military and non-military targets from the thinking of American military leaders.

The restraint in the use of U.S. air power appears to have been primarily motivated by a desire to avoid provoking the Soviet Union into a general war, and not out of explicit desires of American leaders to avoid civilian casualties. However, violation of the international norm against attacking civilians seems to have been one of the provocations that Washington wanted to avoid. In the meeting of the National Security Council that had agreed on the wording of MacArthur’s instructions, both President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson expressed their concerns about provoking the Soviet Union. The president insisted that some restrictions were necessary in the instructions. Truman said he only wanted to destroy air bases, gasoline supplies, ammunition dumps, and such places north of the 38th parallel. He was concerned with restoring order below the 38th parallel and did not want to do anything north of the line except that which would “keep the North Koreans from killing the people we are trying to save.” Agreeing with the president, Secretary Acheson said he had no objections to attacks on North Korean airfields and army units but believed no action should be taken outside of North Korea. Acheson had already received an indication of Soviet opposition to a liberal use of American force. The Soviet representative to the United Nations Yakov A. Malik had expressed Soviet displeasure over American planes bombing Korean cities.12 Protests against “the mass annihilation of the peaceful civilian population” of Korea became a regular feature of propaganda from the Soviet Union and its communist allies.13 Apparently Truman and Acheson believed that attacks on targets other than “purely military” ones, in addition to strikes against targets outside of Korea, held a greater risk of provoking the Soviet Union.

MacArthur’s bomber commander General Emmett “Rosy” O’Donnell had no such concerns. O’Donnell led the two groups of B-29 bombers dispatched from U.S. Strategic Air Command to Korea. When O’Donnell first met with MacArthur in Tokyo in early July, he told the U.N. commander that he would like to incinerate the five North Korean cities which contained much of the country’s industries. O’Donnell argued that proper use of his bombers required heavy blows at the “sources of substance” for enemy frontline soldiers. His B-29s were “heavy-handed, clumsy, but powerful,” and they were no good at “playing with tanks, bridges, and Koreans on bicycles.” O’Donnell proposed that MacArthur announce to the world that as U.N. commander he was going to employ, against his wishes, the means which “brought Japan to its knees.” The announcement could ease concerns over harming civilians by serving as a warning, as O’Donnell put it, “to get women and children and other noncombatants the hell out.”

According to O’Donnell, MacArthur listened to the entire proposal and then said, “No, Rosy, I’m not prepared to go that far yet. My instructions are very explicit; however, I want you to know that I have no compunction whatever to your bombing bona fide military objectives, with high explosives, in those five industrial centers. If you miss your target and kill people or destroy other parts of the city, I accept that as a part of war.” MacArthur was not yet ready to destroy entire enemy-held cities, but was willing to accept the risk of unintended harm to civilians.14

After rejecting O’Donnell’s recommendation for incendiary attacks, MacArthur had his commander of the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) General George E. Stratemeyer issue a directive on bombing. It forbade O’Donnell from attacking “urban areas” as targets but authorized strikes against “specific military targets” within urban areas. Two days earlier, Stratemeyer’s director of operations had written a memorandum, approved by the FEAF commander, which said that “reasonable care” should be exercised in air operations “to avoid providing a basis for claims of ‘illegal’ attack against population centers.”15

Accompanying their measures to limit bombing damage to cities, American leaders strongly proclaimed their commitment to avoiding harm to civilians. “The problem of avoiding the killing of innocent civilians and damages to the civilian economy is continually present and given my personal attention,” General MacArthur asserted in his public reports to the U.N.16 In response to a flood of accusations from communists,17 Secretary Acheson denied that U.N. forces were “bombing and killing defenseless civilians.” Acheson said that U.N. air strikes in Korea had been “directed solely at military targets of the invader” and that these targets were “enemy troop concentrations, supply dumps, war plants, and communication lines.” Any harm to civilians, Acheson suggested was the fault of the North Koreans. The Secretary accused the North Koreans of compelling civilians to labor at military sites, using peaceful villages to hide tanks, and disguising their soldiers in civilian clothes.18

As the early months of the fighting demonstrated, the Korean War began as World War II had, with efforts to distinguish between military targets and civilians and public condemnation of attacks against noncombatants. The devastating aerial campaigns of 1945 had not annihilated the norm against targeting civilians nor made indiscriminate destruction inevitable. However, the Korean War, like World War II, would demonstrate a dynamic of escalation that rendered the persisting norm against targeting civilians largely impotent to actually save civilians from harm.19

In early November 1950, when U.N. soldiers first fought with Chinese units, the U.N. Command adopted a policy of the purposeful destruction of cities in enemy hands. The Far East Air Force began incendiary raids against urban areas reminiscent of those of World War II, and MacArthur spoke privately of making the remaining territory held by the North Koreans a “desert.”20 Yet, as they had during World War II, American leaders persisted in describing their escalated aerial attacks as discriminating strikes against military targets. However, as Chinese intervention threatened U.N. forces, U.S. commanders stretched the definition of “military target” far beyond its usual meaning.

This elasticity tied to a dynamic of escalation was visible from the opening of the U.N. fire-bombing campaign. As one of its first objectives, the U.N. command selected for destruction the city of Sinuiju, a provincial capital with an estimated population of over 60,000, that was across the Yalu River from the Manchurian city of Antung. In October, General MacArthur had restrained his FEAF commander General Stratemeyer in bombing the city. Stratemeyer had asked for the authorization of an attack “over the widest area of the city, without warning, by burning and high explosive,” but he was willing to settle for an attack only against “military targets in the city, with high explosive, with warning.” Here Stratemeyer was still distinguishing between specific military targets within a city and attacks on the city as a whole.

Stratemeyer offered no direct military justification for the attack but instead argued that Sinuiju could be used as the capital of North Korea once Pyongyang was evacuated, which would provide more legitimacy to the communist government than if it were a refugee government on foreign soil. He also believed the psychological effect of a “mass attack” would be “salutary” to the Chinese across the Yalu. The closest Stratemeyer came to a military justification for the attack was his observations that the city served as a rail exchange point between Korea and Manchuria and that the city had considerable industrial capacity that could provide “some means” of supporting a North Korean government, but he did not tie either of these points to the fighting then occurring. MacArthur’s headquarters returned a reply to Stratemeyer’s suggestion the next day that read: “The general policy enunciated from Washington negates such an attack unless the military situation clearly requires it. Under present circumstances this is not the case.” MacArthur was still refusing his air commanders’ pleas for incendiary attacks, but this would not last long.21

On November 3, Stratemeyer again asked MacArthur for permission to destroy Sinuiju. That day Stratemeyer forwarded the request of General Earle E. Partridge, commander of the Fifth Air Force, for clearance to “burn Sinuiju” because of heavy antiaircraft fire from the city and from Antung. Later in the afternoon, Stratemeyer met with MacArthur to discuss the request. Their conversation demonstrated the subjectivity of a “military target” for the U.N. commanders, especially when they had motivations for escalating attacks. General MacArthur told Stratemeyer that he did not want to burn Sinuiju because he planned to use the town’s facilities once the 24th Division seized it. MacArthur did grant permission to send fighters to attack the antiaircraft positions in Sinuiju with any weapon desired, including napalm. Stratemeyer then raised the subject of the marshalling yards near the bridge between Sinuiju and Antung, and MacArthur told him to bomb the yards if Stratemeyer considered them a military target.

At the meeting, Sinuiju was spared from burning, but another North Korean city was not so lucky. MacArthur desired an increase in the use of the B-29s which had run short of targets to bomb, and so he was sympathetic to Stratemeyer’s further recommendation to attack the town of Kanggye. The Air Force commander suggested the FEAF could burn several towns in North Korea as a lesson and indicated that Kanggye was a communications center for both rail and road and was occupied, he believed, by enemy troops. MacArthur answered: “Burn it if you so desire. Not only that, Strat, but burn and destroy as a lesson any other of those towns that you consider of military value to the enemy.” MacArthur left the decision to his air commander. Apparently, MacArthur did not feel the towns to be so vitally important to the enemy’s war effort that it was obvious to him that they had to be destroyed, but Stratemeyer’s idea about teaching the communists a lesson appealed to him. After the meeting, Stratemeyer informed Partridge of MacArthur’s decision not to burn Sinuiju but instead only to authorize strikes against the antiaircraft batteries in and around the city.22

MacArthur’s prohibition on burning Sinuiju lasted only a few hours this time. The general may have changed his mind because of the intelligence he was then receiving that more than 850,000 Chinese soldiers had gathered in Manchuria. By the evening, MacArthur’s chief of staff told Stratemeyer that the burning of Sinuiju had been approved. On November 5, MacArthur conveyed his new instructions to his air commander. Stratemeyer wrote in his diary that the “gist” of these instructions was: “Every installation, facility, and village in North Korea now becomes a military and tactical target.” The only exceptions were to be hydroelectric power plants, the destruction of which might provoke further Chinese intervention, and the city of Rashin, which was close to the Soviet border.

Stratemeyer demonstrated a single-mindedness in carrying out MacArthur’s wishes even at the risk of unwanted destruction. Stratemeyer’s staff pointed out to him how reported sites of POW camps, hospitals, and prisons would be vulnerable to incendiary attack. The Air Force commander later wrote in his diary about the danger to these sites, “Whether vulnerable or not, our target was to take out lines of communication and towns.” Stratemeyer sent orders to the Fifth Air Force and Bomber Command “to destroy every means of communications and every installation, factory, city, and village.” In reviewing Stratemeyer’s orders, MacArthur had him add a sentence that explained the rationale for the escalation. Inserted immediately after the phrase about destroying all communications and settlements, the sentence read, “Under present circumstances all such have marked military potential and can only be regarded as military installations.”23

Stratemeyer also evidenced some concern over justifying the new attacks. He was troubled to learn that ten media correspondents would accompany the B-29 raid on Kanggye. After consulting with his vice commanders and his public information officer, he decided on a general statement on the bombing if asked: “That wherever we find hostile troops and equipment that are being utilized to kill U.N. troops, we intend to use every means and weapon at our disposal to destroy them, that facility, or town. This will be the answer to the use of the incendiary-cluster type of bombs.” Stratemeyer included a similar rationale in his cable to the Air Force chief of staff on the attack: “Entire city of Kanggye was virtual arsenal and tremendously important communications center, hence decision to employ incendiaries for first time in Korea.”24

Several points are worth stressing about these remarkable exchanges between MacArthur and his air commander. Before MacArthur decided to escalate, the U.N. commander and Stratemeyer were distinguishing the targeting of specific structures defined as military targets from the targeting of urban areas as such. The anti-aircraft batteries in Sinuiju were the clear example of a “military” target, but even before the decision to escalate, some targets were more ambiguous such as the city’s marshalling yards. The commanders were also tempted to initiate area attacks because of their beliefs in the potential political and psychological effects the strikes might have on the enemy, even though those effects were at best indirectly related to the actual fighting then occurring.

However, it is crucial to note that the generals never explicitly defined civilians as legitimate targets, even though Stratemeyer readily risked the destruction of hospitals, POW camps, and prisons.

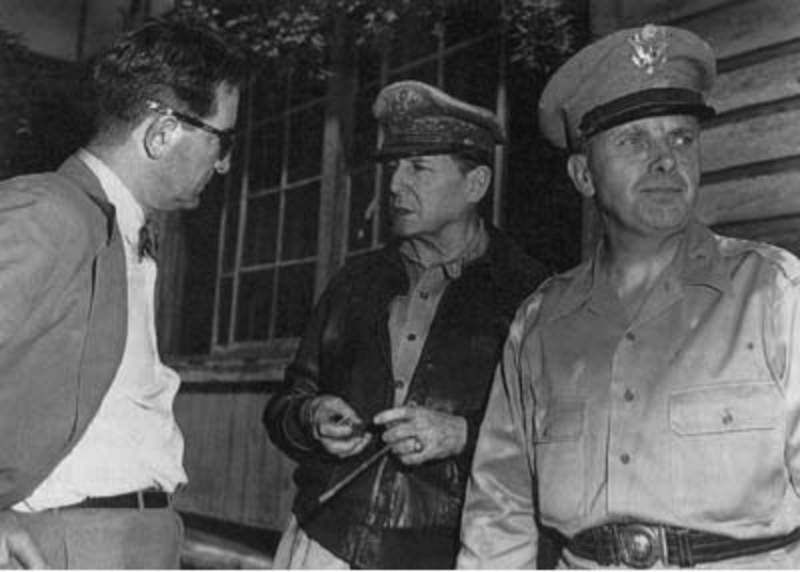

Bombs Away regardless of the type of enemy target lying in this rugged, mountainous terrain of Korea, very little would remain after the falling bombs have done their work. This striking photograph (above) of the lead bomber was made from a B-29 “Superfort” of the Far East Air Forces 19th Bomber Group on the 150th combat mission the 19th Bomber Group had flown since the start of the Korean war, ca. 02/1951

Bombs Away regardless of the type of enemy target lying in this rugged, mountainous terrain of Korea, very little would remain after the falling bombs have done their work. This striking photograph (above) of the lead bomber was made from a B-29 “Superfort” of the Far East Air Forces 19th Bomber Group on the 150th combat mission the 19th Bomber Group had flown since the start of the Korean war, ca. 02/1951

The generals escalated the war by targeting the physical infrastructure of cities and sought political and psychological benefits from this destruction, but there is no evidence that they talked, even privately among themselves, about aiming to kill enemy civilians or about gaining benefits from those civilian deaths. It is conceivable that killing civilians could have been their underlying intention and motivation, but it is exceedingly difficult to demonstrate convincingly an individual’s state of mind at a given time, and the historical evidence that has yet come to light does not suggest that the U.N. commanders were thinking specifically about killing civilians.

The episode did demonstrate the instability of the definition of a military target which slid within hours from preventing the burning of Sinuiju to justifying it. Instead of defining anti-aircraft batteries and railroad yards as the only military targets in Sinuiju, MacArthur redefined the entire physical infrastructure of the city as a military target, and showed how quickly structures usually considered civilian became open for attack. With the potential for media attention to the new incendiary raids, Stratemeyer employed new, and possibly disingenuous or muddled, attempts to obscure or justify the escalation. The attack on Kanggye, which he had justified to MacArthur for its potential as a “lesson” and for its transportation capacity and its possible housing of enemy troops, suddenly became necessary because the city was a “virtual arsenal” and a “tremendously important communications center.” While some of these points may sound like the second-guessing of difficult military decisions based on the limited information of historical hindsight, even if one agrees with every decision MacArthur and Stratemeyer made, their conversations suggested that pressures to escalate stretched the definition of military targets well beyond its common usage.

The “fire job,” which General O’Donnell had advocated in July but Washington had forbidden as too provocative, commenced in early November. Unlike the summer retreat of 1950, Washington did not restrain MacArthur, likely because the wider war feared earlier had already broken out, with the Chinese instead of the Soviets. On November 8, the FEAF showered 500 tons of incendiary bombs on more than one square mile of Sinuiju’s built-up area, destroying 60 percent of the city.

In O’Donnell’s report on the work of his bombers, he declared that “the town was gone.” Other towns were to follow. By November 28, Bomber Command reported that 95 percent of the town of Manpojin’s built up area was destroyed, for Hoeryong 90 percent, Namsi 90 percent, Chosan 85 percent, Sakchu 75 percent, Huichon 75 percent, Koindong 90 percent, and Uiju 20 percent. The destruction continued into the winter as Chinese forces compelled the U.N. soldiers to retreat south. As U.N. units withdrew from the major North Korean cities, those cities too became targets. On December 30, the FEAF commander informed his subordinates that they had the authority to “destroy” Pyongyang, Wonsan, Hamhung, and Hungnam, four of North Korea’s largest cities. The FEAF conducted the attacks without warning to the civilian population, and purposefully avoided publicizing the strikes. By the end of the war, eighteen of twenty-two major cities in North Korea had been at least half obliterated according to damage assessments by the U.S. Air Force. The fire-bombing of North Korean communities that commenced in November made meaningless the earlier claims of the FEAF that their bombing operations avoided the destruction of residential areas.25

However, just as during World War II, Americans’ depiction of their fighting as employing discriminating means changed little. Military officers and the press proceeded to discuss the violence in Korea as if its application remained discriminate and as if risks to noncombatants had not increased. The objects of attack were still “military targets” but the implicit definition of the term “military target” had grown to include virtually every human-made structure in enemy-occupied territory. The norm against targeting civilians survived within this definition, in the sense that Americans never came to the point of arguing that the civilian population itself was a “military target” and therefore a legitimate object of attack, but the expanded definition of the term and the acceptance of the destruction it entailed offered meager protection for Korean civilians.

While avoiding direct acknowledgment that U.N. forces were systematically burning North Korean cities, the U.N. Command did admit that it had escalated the air war. U.N. commanders offered new justifications for the expanded destruction that clung to the notion that its airplanes were attacking military targets. The justifications were far distant from the Air Force’s primary vision of how a strategic air offensive should be conducted. As Air Force leaders had been claiming from before World War II and had reiterated during the “Revolt of the Admirals” in 1949, the purpose of strategic air power was to destroy war-supporting industries in order to deprive the enemy’s forces in the field of weapons, ammunition, and supplies. Shortly before he left his post as head of Bomber Command, General Emmett O’Donnell said in an interview that his bombers had been prevented from destroying the enemy’s true sources of supply in China and the Soviet Union and therefore had been prevented from doing the job that they were made to do.26

Instead, the Air Force viewed its escalated bombing in Korea as part of a campaign to interdict the flow of weapons, supplies, and additional men to the communist army in Korea, and explained it to the public as such. But the campaign went beyond precise attacks against transportation and communication systems in North Korea in which bridges, railroad yards, docks, and vehicles were targets. U.N. forces undertook the destruction of entire towns, particularly those along major transportation routes from Manchuria and the Soviet Union, in order to deprive the communists of shelter in which to conceal their supplies and soldiers from the U.N. airplanes. The destruction also stripped the enemy soldiers of protection from the elements during the winter campaign

Nevertheless, the U.N. forces rarely acknowledged that this escalation was destroying entire communities and placing Korean civilians at risk. Public communiques from the U.N. Command avoided discussing or justifying the destruction of Korean towns and villages directly.

Instead, the press releases named “buildings,” often identified as enemy-occupied or as structures for storing, as the usual target of U.N. airplanes, disaggregating the communities into their constituent structures. Besides being regularly mentioned as the object of attack in the daily releases on air operations, buildings destroyed became part of the public and internal measure of progress of the air campaign. A January 2, 1951 release, labeled the six-month “box score,” placed the Navy total for buildings destroyed at 3,905. These buildings were presumably not ammo dumps, command posts, fuel dumps, observation positions, radio stations, roundhouses, power plants, or factories because the tallies listed those categories separately. The Air Force introduced the category of “enemy-held buildings” into their press release target tallies in the fall of 1951 and by that time they were advertising the destruction of more than 4,000 buildings a month and over 145,000 since the beginning of the war. Within the Air Force, the square footage of buildings destroyed eventually became a semi-official measure of progress in the air campaign. Towns and villages divided up into their constituent “buildings” by official press releases proved a much less controversial target for demolition than the blatant admission that American air power was leveling much of the Korean peninsula.27

Instead, the press releases named “buildings,” often identified as enemy-occupied or as structures for storing, as the usual target of U.N. airplanes, disaggregating the communities into their constituent structures. Besides being regularly mentioned as the object of attack in the daily releases on air operations, buildings destroyed became part of the public and internal measure of progress of the air campaign. A January 2, 1951 release, labeled the six-month “box score,” placed the Navy total for buildings destroyed at 3,905. These buildings were presumably not ammo dumps, command posts, fuel dumps, observation positions, radio stations, roundhouses, power plants, or factories because the tallies listed those categories separately. The Air Force introduced the category of “enemy-held buildings” into their press release target tallies in the fall of 1951 and by that time they were advertising the destruction of more than 4,000 buildings a month and over 145,000 since the beginning of the war. Within the Air Force, the square footage of buildings destroyed eventually became a semi-official measure of progress in the air campaign. Towns and villages divided up into their constituent “buildings” by official press releases proved a much less controversial target for demolition than the blatant admission that American air power was leveling much of the Korean peninsula.27

The tank of napalm dropped by Fifth Air Force B-26 Invader light bombers of the 452nd Bomb Wing (light) on this Red marshalling yard at Masen-ni, North Korea, has blended with a stockpile of supplies on a loading platform to from a fiery inferno, ca. 07/11/1951

The press releases of the U.N. Command also avoided directly acknowledging attacks on entire villages and towns by the use of the term “supply center” and similar phrases such as “communications center,” “military area,” and “build-up area.” MacArthur’s public report to the United Nations on military operations during the first half of November described the escalation in the air war this way: “Command, communication and supply centers of North Korea will be obliterated in order to offset tactically the handicap we have imposed upon ourselves strategically by refraining from attack of Manchurian bases.”28 With the fall escalation, the daily press releases began to make vague references to strikes against supply centers. Sometimes the wording of the releases would use a Korean town name interchangeably with the phrase supply center implying that they were one and the same. More often the releases would report attacks against supply centers “at,” “in,” or “of,” a Korean town or city: “the supply center of Hamhung,” for example. These prepositional phrases could imply either that the entire town was considered by the U.N. forces a supply center or that the town contained within it a supply center. Only rarely would the releases explicitly identify the Korean place names referred to as villages, towns, or cities. With “supply center” identified as a military target, use of the term and similar phrases helped to maintain the perception that U.S. forces were only attacking military targets.29

However, the reliance of the press releases on describing operations as attacks on “buildings” and “supply centers” was not always enough to quiet the U.N. Command’s fears about the American image in Korea. In August 1951, the U.N. Command’s Office of the Chief of Information wrote a memorandum for the Public Information Office of the Far East Air Force. The memo said that General Matthew B. Ridgway, MacArthur’s replacement, had suggested that in news releases of targets destroyed by air attacks, the Air Force publicists might “specify more definite military targets” such as tanks, anti-aircraft guns, or armored vehicles. This would prevent anyone from pointing to the releases as evidence that American forces were “wantonly attacking mass objectives such as cities and towns” in North Korea. The U.N. Command, despite its expanded air attacks, continued to present the war it was waging as a discriminate use of force directed solely against military targets.30

These press relations efforts met with considerable success in the United States. Press coverage of the escalated air assault did not challenge the comforting picture the U.N. Command presented. Newspapers did note the U.N. forces had initiated some of the largest air strikes of the war in November and occasionally acknowledged the burning of entire cities. Nevertheless, the reporting indicated the military usefulness of destroying the physical infrastructure and avoided discussing the impact of the destruction on civilians.31 This picture of a discriminate use of air power in Korea has survived in many of the historical treatments of the war including the official Air Force history32 and a number of popular military histories and cursory scholarly accounts of the air war in Korea.33 Only recently have Americans begun to acknowledge the full extent of the fire bombing campaigns in histories of the Korean War.34

As in World War II, U.S. air power inflicted massive harm on civilians during the Korea War, and diverged from the customary practice of sparing civilians from the violence of war. However, this violence came through a process of escalation during the war. Area bombing did not supplant precision bombing as the standard method of employing air power against an enemy, but it remained an option when the fighting escalated. Even with the undeniable widespread harm Korean civilians suffered from U.S. weapons, Americans clung to the normative value of avoiding direct attacks against noncombatants, a norm buttressed by international humanitarian law and the precedents of Nuremberg. They almost never advocated publicly or privately, within the armed forces or outside them, the purposeful targeting of civilian populations as such. The stunning contradictions between lethal consequences and proclaimed scrupulousness were eased by the elastic definitions of military targets, but other changes in thinking about harming civilians assisted in this tortured reconciliation as well.

One of the most significant changes was the emerging emphasis on intention as the crucial distinction between justifiable and unjustifiable harm to civilians in war. Americans and a broader transnational consensus, which was eventually reflected in international humanitarian law, placed less importance on whether civilians were killed than on whether they were killed intentionally. It was not that intentional killing was identified as a new wrong after World War II, the norm against attacking civilians had all along implied prohibition of intentional attacks. It was rather that the massive expansion of firepower that was difficult to control, as exemplified by American air power, created a novel cultural space for plausible unintentional destruction on a tremendous scale. When wars were fought with spears, or even with cannon or rifles, the relative ease with which these weapons could be directed against a specific target left little room for questions of intent. In face-to-face warfare, warriors attacked individuals that they could identify as combatants or as bystanders. Mistakes could be made, but these occurred under unusual circumstances such as in combat at night or in fog. In most close fighting, intention was manifest in action. Either warriors killed noncombatants purposefully or they spared them. With the introduction of weapons that killed over long distances and devastated great areas, intent no longer clearly followed from action. Common and widespread unintended destruction became plausible. The great acceleration of this trend toward uncontrollable firepower in the twentieth century contributed to making intention crucial to Americans’ thinking about attacking civilians. Americans rationalized harm to noncombatants from violence that they could not control as a tragedy of war but not a crime.

The Korean War clearly illustrated this preoccupation with intention. Americans’ public insistence throughout the war that they discriminated between military targets and civilians sought to demonstrate that Americans did not intend to kill civilians. In addition to their extensive talk about intentions, Americans pointed to their military’s efforts to warn civilians of air attacks and evacuate them from combat areas. U.N. forces regularly broadcast warnings to civilians by radio and loudspeaker, and conducted a number of operations where warning leaflets were dropped on communities.35 These warnings, while of dubious value in actually protecting civilians, were well covered by the American media.36 U.N. forces also tried to assist civilians by conducting several large operations to evacuate them out of harm’s way during the winter retreat. In December 1950 as the Navy was evacuating X Corps from Hungnam, the Americans made room on their ships for 91,000 refugees. The U.N. Command also relocated thousands of refugees, including an airlift of 989 orphans, to the islands off South Korea’s coast during the winter.37 Even though these evacuations assisted only a small fraction of the Koreans who were threatened by the war’s violence, the U.S. press lauded these operations as well as other well-intentioned deeds by American soldiers on behalf of civilians.38

After the war, the U.S. Army’s revised field manual on the law of land warfare introduced a new statement that expressed as doctrine the growing importance of intention. The revised 1956 manual said, “It is a generally recognized rule of international law that civilians must not be made the object of attack directed exclusively against them.”39 Previous army manuals had left this rule unexpressed. As a subculture, military professionals may have placed even more emphasis on their intentions not to harm noncombatants even in the face of widespread civilian deaths. While the sources make it difficult to assess the personal sentiments of officers and soldiers about civilian casualties during the Korean War, it is not hard to believe that many in private did not want to think of themselves as waging war against defenseless civilians.40

This focus on intentions assisted in leaving the vital core of a norm against attacking civilians intact. Americans did not come to accept the targeting of civilians as a legitimate method in the Korean War. Nevertheless, the focus on intentions encouraged by new air power capabilities created a tendency in American thinking that was extremely dangerous to civilians in war. Americans came to condone unintended civilian casualties as an acceptable human cost of war, what would later be called “collateral damage.”41

How many unintended deaths could be justified in pursuing military objectives was a calculation usually absent from the Korean War era discussions of U.S. commanders and from the wider media attention to the suffering of Korean civilians. However, the beginning of a revival in just war thought started to raise these questions of proportionality, at least among theologians and scholars. In the first half of the twentieth century, only a few Catholic theologians had published studies in the United States which considered in any depth the problem of morality and warfare. In the early 1950s, just war reasoning reemerged in the hypothetical discussions of a feared nuclear war,42 and by the late 1950s, the just war tradition was undergoing a scholarly rebirth.43 One obscure principle from just war thought, the principle of double effect, had great relevance to the dilemmas of justifying unintended harm to civilians and gauging proportional harm. Derived from the teachings of Thomas Aquinas, the principle of double effect acknowledged that a given action could have multiple consequences, some of them good and some of them bad. As theologians and moral philosophers formulated the principle in the twentieth century, it held that as long as only the good consequences of an action were intended, the evil results were not a means to the good outcome, and the positive benefits outweighed the negative, such an action was morally justified.44 For example, the Catholic University theologian Father Francis J. Connell argued along these lines in debates during the Korean War over the morality of using nuclear weapons. He argued that a limited killing of noncombatants might be justified by the military advantage gained through the destruction of a crucial military target.45 Others like the British theologian F. H. Drinkwater criticized the use of the principle to rationalize unintended harm. Drinkwater argued that use of an atomic bomb against a city without a warning to the population was certain to kill tens of thousands of civilians. Since this evil was certain, he asserted it was hypocrisy to claim that it was not intended.46 While it is difficult to demonstrate that the dilemmas over justifying unintended harm which the new bombing capabilities raised was a direct spur to the revival of just war thinking, the principle of double effect has since served as a common justification for unintended harm.

International humanitarian law evolved slowly to reflect the changing norms about bombing and attacking civilians and the increased importance of intention, but the laws have lagged far behind broader attitudes. When the 1949 Geneva Conventions were revised following the experiences of World War II, they were almost completely silent on the threat to civilians from bombing. Although negotiators composed an entirely new convention for the protection of civilians in wartime, the protections concerned almost exclusively civilians in occupied territory and not civilians still behind their side’s frontlines who were the people who were most vulnerable to strategic bombing. At the 1949 Geneva conference, the Americans and the British opposed both the inclusion of restrictions on bombing and the Soviet Union’s attempts to use the treaty to outlaw atomic weapons. Two of the American negotiators later wrote, “It is to be emphasized that these ‘grave breaches’ do not constitute restrictions upon the use of modern combat weapons. For example, modern warfare unfortunately and often may involve the killing of civilians in proximity to military objectives, as well as immense destruction of property.”47 The 1949 agreements shielded only hospitals from all forms of attack, including bombing, and otherwise proposed voluntary establishment of safety zones where noncombatants could be sheltered from the effects of war. Although the United States and the U.N. forces agreed to abide by the Geneva Conventions in Korea, the laws provided few impediments to the use of American air power. When the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations raised the idea of the creation of safety zones in Korea to protect women, children, and the elderly from the ravages of war, the United States rejected the proposal out of concern that neutral observers could not be found to ensure that the safety zones in North Korea were not contributing to the war effort.48

LEGACIES

After the Korean War, the ICRC began to circulate draft rules for the protection of civilian populations from the dangers of indiscriminate warfare, but it took years for protections against targeting civilians to be written into international law. In 1968, the U.N. General Assembly affirmed a Red Cross resolution that banned attacks against civilian populations as such. In 1977, an international conference completed the drafting of two additional protocols to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. The first and second protocols, which related to the protection of victims of international and non-international armed conflicts respectively, each included the provision: “The civilian population as such, as well as individual civilians, shall not be the object of attack. Acts or threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited.”49 Only slowly did international law come to embody the increased importance of intention that the norm against targeting civilians had acquired.

Beyond the growing importance of intention in defining legitimate uses of force in war, it is much more challenging to assess the legacy of the rise of bombing after World War II on norms because of the changing nature of conflicts the United States fought after Korea, and the unavailability of crucial sources. Despite these challenges, one normative belief appears to have been firmly established among American military leaders, and to have become noncontroversial among a wider public: that the weapons of war and military supplies before they found their way to soldiers’ hands were a worthy target. Bombing behind the frontlines of battle opened up the possibility of destroying arms and supplies before they could be used by enemy forces, either through attacks on factories or the transportation networks through which this matérial flowed. This disarming strategy was the favorite justification of bombing by commanders and civilian advocates of air power as was clearly shown during the Korean War.50 The U.S. Army’s 1956 field manual on the law of land warfare also incorporated this new understanding into the revisions of the previous manual from 1940. In narrowing the Hague Convention prohibition on the bombardment of undefended places, the manual clarified that this did not preclude strikes against military supply. The new manual said, “Factories producing munitions and military supplies, military camps, warehouses storing munitions and military supplies, ports and railroads being used for the transportation of military supplies, and other places devoted to the support of military operations or the accommodation of troops may also be attacked and bombarded even though they are not defended.”51 These parts of civilian society behind the frontline were deemed a vital component of a war effort, and few during the Korean War or since have challenged the legitimacy of these sources of supply as targets. The distinctions between civilian and military and defended and undefended became less important than the difference between noncombatant and combatant and an individual’s or resource’s relationship to the actual violence of war. Just as a civilian factory could produce supplies for the military, a soldier could become a noncombatant once wounded and incapacitated. An individual’s or resource’s relationship to the actual violence of war became the most important determinant of whether they were legitimate targets for attack.

While Americans embraced the targeting of clearer sources of military supply, bombing entire cities and urban areas has stayed consistently controversial, both on grounds of moral principle and effectiveness, even though a literal distinction could be made between the physical structures of an urban area and the civilian populace, as was often done in the Korean fighting. Military leaders in World War II, Korea, and afterwards have gone to great lengths to avoid openly acknowledging the destruction of cities as such. Although preparations for nuclear war often clearly envisioned targeting cities, this open acknowledgement was a major factor in making nuclear war repugnant.52

Other changes in thinking about bombing civilians are much more difficult to assess. For example, the subjectivity in choosing “military” targets has not necessarily decreased in the wars since Korea. Given the elaborate expressions of official American concern over civilian casualties, it might be tempting to argue that the wars in the Persian Gulf, Iraq, and Afghanistan have encouraged more precise and rigid definitions of military targets. Nevertheless, these definitions have not been tested, as they were in the Korean War. These later wars have been severely asymmetrical conflicts and American forces and commanders were not strained in the ways they were in Korea, let along during World War II. Definitions of military targets may still be elastic but recent wars may not have necessitated the type of escalation that encouraged this flexible thinking.

In other areas where changes in thinking about bombing civilians might seem apparent, a closer examination may reveal their superficiality. Indisputably, the United States has conducted less area bombing in its wars since Korea, but this could simply be because it has fought fewer evenly matched wars and has faced fewer desperate decisions to escalate. It might also be tempting to believe that American commanders in recent wars have resisted the temptations to which MacArthur and his air commanders succumbed of justifying bombing attacks for their political and psychological effects instead of for their directly military impact. However, limited current access to sources and records about these highly classified internal discussions hampers a full assessment.

Finally, more active efforts to avoid civilian casualties in recent American wars such as the expanded role of operational law and military lawyers in targeting may be more a result of the rise of counterinsurgency thinking than evidence of a growing belief among Americans that killing civilians is wrong. Counterinsurgency doctrine has emphasized the importance of winning the support of civilian populations in civil wars as a means to military victory. From Vietnam to Afghanistan, American commanders have tried to limit civilian casualties in order to avoid alienating civilians.53 The rise in counterinsurgency doctrine is an important change in military thought, but one tied more to the changing nature of American wars than to norms about bombing civilians.

In assessing changing norms about bombing after World War II, it is crucial to distinguish among the changes in values, ideas, laws, and behavior that the term “norm” can encompass. These distinctions make it easier to summarize how norms about bombing changed after World War II. The transnational normative value that prohibited attacks on civilians persisted. However, the actual protections it offered to civilians were undermined by the new bombing capabilities. Because of the difficulties with controlling the violence of modern weaponry, the focus on intention gained great significance in moral justification, and this focus helped rationalize, along with the obscure moral principle of double effect, unintended harm and contributed to a complacent stance toward the terrible human cost of collateral damage. On the other hand, normative behavior or customary practice did change, at least temporarily, during both World War II and Korea. As the wars escalated, U.S. armed forces conducted unprecedented fire-bombing and other area attacks against cities and towns that proved deadly to civilians, and the flexibility of the definition of “military targets” facilitated these area attacks. International humanitarian law also evolved to catch up with the growing significance of intentional attacks, but at a relatively slow rate. Finally, while normative beliefs about bombing civilians are the hardest to assess, Americans have come to accept the idea that bombing behind the frontlines with the goal of disarming was an effective and acceptable method of fighting even while they remained hotly divided over attacks on urban areas.

The decade after World War II and the experience of the Korean War laid a foundation for the sensitivity to civilian casualties that became evident in the American wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This foundation was not built through a recovery of the norm against targeting civilians spurred by the trauma of the Vietnam War after a period when the norm had been abandoned. The role of the Vietnam War in changing American attitudes toward civilian casualties was not so crucial because many of these changes, such as the growing significance of intention, began earlier, and because much about these attitudes has remained relatively constant from the 1930s to the 1970s and has remained so into the twenty-first century. Instead, the Korean War experience demonstrated the durability of the norm against targeting civilians even in the face of mass killing from bombing or otherwise. Adherence to the norm persisted even though the norm provided severely limited protections to civilians when bombing was employed and conventional wars escalated. In avoiding massive killing of civilians in their wars since Vietnam, Americans may not have become more virtuous, but only more fortunate in not having to fight more evenly matched wars.

This article is an expanded and adapted version of the chapter “Bombing Civilians After World War II: The Persistence of Norms Against Targeting Civilians in the Korean War” from Matthew Evangelista and Henry Shue (eds.), The American Way of Bombing: How Ethical and Legal Norms Change, from Flying Fortresses to Drones (Cornell University Press, 2014).

Sahr Conway-Lanz is Senior Archivist for American Diplomacy at the Yale University Library. He is the author of Collateral Damage: Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity After World War II (Routledge, 2006). His article “Beyond No Gun Ri: Refugees and the United States Military in the Korean War” that appeared in Diplomatic History won the Bernath Article Prize in 2006. He has a Ph.D. in history from Harvard University and is currently working on a book project about how Americans have held their own soldiers accountable for harming civilians in war.

Notes

1 For such arguments, see George E. Hopkins, “Bombing and the American Conscience during World War II,” Historian 28, no. 3 (1966): 451–73; Richard Shelly Hartigan, The Forgotten Victim: A History of the Civilian (Chicago: Precedent, 1982), 1–10; Ronald Schaffer, Wings of Judgment: American Bombing in World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 3, 217–18; H. Bruce Franklin, War Stars: The Superweapon and the American Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 105; Paul Boyer, Fallout: A Historian Reflects on America’s Half-Century Encounter with Nuclear Weapons (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1998), 12; John W. Dower, Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor/Hiroshima/9–11/Iraq (New York: W.W. Norton and New Press, 2010), 161, 166–70, 192–96. For a contrary view, see Biddle in Matthew Evangelista and Henry Shue (eds.), The American Way of Bombing: Changing Ethical and Legal Norms, from Flying Fortresses to Drones (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014).

2 Congressional Record, 75th Cong., 3rd sess., vol. 83, pt. 8: 9524-9526, 9545; Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, vol. 8 (New York: Macmillan, 1941), 454.

3 See, for example, New York Times, April 29, May 10, 1940.

4 Schaffer, Wings of Judgment, 70; Conrad C. Crane, Bombs, Cities, and Civilians: American Airpower Strategy in World War II (Lawrence, KA: University of Kansas Press, 1993), 31.

5 New York Times, February 25, 1945; Michael S. Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987), 289.

6 Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Harry S. Truman, 1945 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1961), 197, 212.

7 Crane, Bombs, Cities, and Civilians, 29-30.

8 For an early example of this, see Conference minutes, July 7, 1949, box 2389, 514.2, Central Decimal Files 1945-1949, Record Group (hereafter RG) 59, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (hereafter NA).

9 Sahr Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage: Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity after World War II (New York: Routledge, 2006), 23-26.

10 U.S. House Committee on Armed Services, The National Defense Program—Unification and Strategy: Hearings, 81st Cong., 1st sess., 1949, 183-189, 402-403.

11 Message, Joint Chiefs of Staff to MacArthur, June 29, 1950, FRUS 1950, vol. 7, 240-241.

12 Draft notes on June 29, 1950 White House defense meeting, box 71, Elsey Papers, HSTL; memorandum of conversation, Philip C. Jessup, June 29, 1950, box 4263, 795.00, Central Decimal Files 1950-1954, RG 59, NA; message, Warren R. Austin to Acheson, June 27, 1950, FRUS 1950, vol. 7, 208-209.

13 United Nations Security Council Official Records, August 8, 1950, 5th year, 484th mtg., S/PV.484, 20.

14 O’Donnell to LeMay, July 11, 1950, box 65, series B, Curtis E. LeMay Papers, Library of Congress (LC).

15 Stratemeyer to O’Donnell, July 11, 1950, box 103, Series B, LeMay Papers, LC; HQ USAF, An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the United States Air Force in the Korean Campaign (Barcus Report), vol. 5, 2, box 906, Project Decimal Files 1942-1954, Directorate of Plans, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, RG 341, NA.

16 New York Times, September 3, 1950. See also “Report of the United Nations Command Operations in Korea,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, October 2, 1950, 534-540; “Fifth Report of the U.N. Command Operations in Korea,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, October 16, 1950, 603-606.

17 Message, London Embassy to Secretary of State, July 1, 1950, box 4264, 795.00, Central Decimal Files 1950-1954, RG 59, NA.; New York Times, July 4, 11, 12, 14, 18, 26, 1950; message, Moscow Embassy to Secretary of State, July 14, 1950, box 4265, 795.00, Central Decimal Files 1950-1954, RG 59, NA; message, Moscow Embassy to Secretary of State, July 17, 1950, box 4265, 795.00, Central Decimal Files 1950-1954, RG 59, NA; Daily Worker, July 4-6, 10, 12, 14, 17, 18, 20, 24-28, 31, 1950; United Nations Security Council Official Records, August 8, 1950, 5th year, 484th mtg., S/PV.484, 20. The Soviet Union also led a campaign among communist countries to raise relief funds for the Korean victims of American “terror bombing.” “From Korea Bulletin 1 August 1950,” box 1, Korean War Communiques and Press Releases 1950-1951, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA; New York Times, August 3, 1950. Seoul City Sue, the English-speaking commentator for North Korean radio broadcasts to U.N. forces, excoriated the U.S. Air Force for promiscuous bombing of schools and the strafing of farmers. Message, CINCFE to UEPC/Department of the Army, August 8, 1950, box 199, 311.5, Classified Decimal File 1950, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA.

18 “North Korea Slanders U.N. Forces to Hide Guilt of Aggression,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, September 18, 1950, 454.

19 I want to thank Alexander B. Downes and his work Targeting Civilians in War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008) for helping me to understand the larger significance of this dynamic of escalation.

20 Memorandum of conversation, Muccio, November 17, 1950, Foreign Relations of the United States (hereafter FRUS) 1950, vol. 7, 1175.

21 William T. Y’Blood (ed.), The Three Wars of Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer: His Korean War Diary (Washington, DC: Air Force History and Museums Program, 1999), 236-237.

22 Ibid., 253-255.

23 Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 366; Conrad C. Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 1950-1953 (Lawrence, KA: University of Kansas Press, 2000), 46; Stratemeyer Diary, 258-261.

24 Stratemeyer Diary, 256-257; message, Stratemeyer to Vandenberg, November 5, 1950, box 86, Vandenberg Papers, LC.

25 Robert Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-1953, rev. ed. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 221-23, 226; New York Times, November 9, 1950; Stratemeyer Diary, 269, 371-72; interview transcript from 98th Bomb Group, November 30, 1950, box 905, Project Decimal File 1942-1954, Directorate of Plans, Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, RG 341, NA; Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 63, 168.

26 New York Times, January 16, 1951.

27 “Korean Release, No. 778,” January 2, 1951, box 3, Korean War Communiques and Press Releases 1950-1951, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA; “Korean Release Unnumbered,” December 2, 1951, box 5, Korean War Communiques and Press Releases 1950-1951, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA; memorandum to Schmelz, October 31, 1951, box 15, Formerly Classified General Correspondence, Public Information Division, Office of Information Services, RG 340, NA; Wiley D. Ganey to LeMay, September 7, 1952, series B, box 65, LeMay Papers, LC.

28 “Ninth Report: For the Period November 1-15, 1950,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, January 8, 1951, 47-50.

29 See the press releases printed daily in the New York Times starting with “Korean Release, No. 627,” November 9, 1950. By spring 1951, references to supply centers or areas as the targets for U.N. air attacks were frequent in the releases. Releases December 1950-December 1951 are also in boxes 2-3, Korean War Communiques and Press Releases 1950-1951, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA. The terms like supply center were not only used by the military for public consumption. Similar terms were used in internal documents by American officers. Message, G-2, Department of the Army to USCINCEUR et al., November 24, 1952, box 756, Chronological File 1949-June 1954, Office of Security Review, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Legislative and Public Affairs, RG 330, NA.

30 Memorandum, Office of the Chief of Information, HQ FEC to Public Information Office, FEAF, August 1, 1951, box 36, Office of the Chief of Information, Office of the Chief of Staff, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, RG 331, NA.

31 Chicago Tribune, November 8, 1950; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 8, 1950; Detroit News, November 8, 1950; Philadelphia Bulletin, November 8, 9, 1950; Los Angeles Times, November 8, 9, 1950; San Francisco Examiner, November 8, 9, 1950; Houston Chronicle, November 8, 9, 1950; Washington Post, November 8-10, 1950; Baltimore Sun, November 8-10, 1950; Boston Post, November 8-11, 1950; New York Times, November 9, 1950; Cleveland Press, November 9, 1950. Of the twelve daily newspapers surveyed, only the Detroit News and Cleveland Press did not label Sinuiju a supply base or similar term. For additional evidence of the wider public embrace of this persisting vision of a war fought with discrimination, see Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage, 114-119.

32 Futrell, United States Air Force in Korea.

33 For example, Max Hastings, The Korean War (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987); Crane, Bombs, Cities, and Civilians, 147-150.

34 Bruce Cumings, The Roaring of the Cataract, 1947-1950, vol. 2 of The Origins of the Korean War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990); Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea; Steven Hugh Lee, The Korean War (New York: Longman, 2001).

35 First Radio Broadcast and Leaflet Group, “Plan for Psychological Warfare Operations Designed to Support the United Nations Air Force,” June 12, 1952, box 20, General Correspondence 1952, Psychological Warfare Section, General Headquarters, Far East Command, RG 338, NA; “Plan for Psychological Warfare Operations in Support of Air Attack Program,” July 7, 1952, box 7, General Correspondence 1952, Psychological Warfare Section, General Headquarters, Far East Command, RG 338, NA; “Monthly Report for August 1952,” box 14, General Correspondence 1952, Psychological Warfare Section, General Headquarters, Far East Command, RG 338, NA; “Report of the U.N. Command Operations in Korea,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, January 26, 1951, 155-159; “Psychological Warfare Weekly Bulletin,” n.d., box 20, General Correspondence 1952, Psychological Warfare Section, General Headquarters, Far East Command, RG 338, NA; Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 122-125; message, CINCFE to PsyWar, October 9, 1952, box 759, Chronological File 1949-June 1954, Office of Security Review, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Legislative and Public Affairs, RG 330, NA; “Reports of U.N. Command Operations in Korea: Sixty-Fifth Report for the Period March 1-15, 1953,” U.S. Department of State Bulletin, July 13, 1953, 52-53.

36 “The Right Track,” Time, July 21, 1952, 32; “Will Bombing End Korean War?” U.S. News and World Report, September 12, 1952, 13-15; “Truth About the Air War,” U.S. News and World Report, November 7, 1952, 20-21; Carl Spaatz, “Stepped-Up Bombing in Korea,” Newsweek, August 18, 1952, 27; New York Times, August 5, 6, 8-10, 19, 21, 29, 30, September 14, 20, October 3, 5, 1952.

37 “Korean Release, No. 761,” December 29, 1950, box 2, Korean War Communiques and Press Releases, 1950-1951, Office of the Chief of Information, RG 319, NA; Ashley Halsey, Jr., “Miracle Voyage Off Korea,” Saturday Evening Post, April 14, 1951, 17; message, X Corps to CINCFE, December 22, 1950, box 729, Security-Classified Correspondence 1950, Adjutant General Section, RG 500, NA; James A. Field, The History of United States Naval Operations: Korea (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962), 304; Robert Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea 1950-1953, Rev. ed. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983), 269.

38 New York Times, December 25, 1950, January 19, February 11, June 16, 1951, July 30, 1951, November 4, 1952, January 14, May 25, 1953; San Francisco Examiner, December 1, 1950; Nora Waln, “Our Softhearted Warriors in Korea,” Saturday Evening Post, December 23, 1950, 28-29, 66-67; “Waifs of War,” Time, January 1, 1951, 16; “The Greatest Tragedy,” Time, January 15, 1951, 23-24; “Helping the Hopeless,” Time, January 29, 1951, 31; Bill Stapleton, “Little Orphan Island,” Collier’s, July 14, 1951, 51; Michael Rougier, “The Little Boy Who Wouldn’t Smile,” Life, July 23, 1951, 91-98; James Finan, “Voyage from Hungnam,” Reader’s Digest, November 1951, 111-112; “Christian Soldiers,” Time, June 15, 1953, 75-76.

39 FM 27-10 Department of the Army Field Manual: The Law of Land Warfare (Washington: Department of the Army, 1956), 16.

40 For an example of the challenge in assessing individual officers’ principled commitments to protecting civilians, see Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage, 52-55.

41 For a more extensive examination of this argument, see Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage.

42 For examples, see St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 1, 1950; Edward A. Conway, “A Moralist, a Scientist, and the H-Bomb,” America, April 8, 1950, 9-11.

43 For examples, see Ralph Luther Moellering, Modern War and the American Churches: A Factual Study of the Christian Conscience on Trial from 1939 to the Cold War Crisis of Today (New York: American, 1956); John Courtney Murray, Morality and Modern War (New York: Church Peace Union, 1959); Roland H. Bainton, Christian Attitudes Toward War and Peace: A Historical Survey and Critical Re-Evaluation (New York: Abingdon, 1960); William J. Nagle, Morality and Modern Warfare: The State of the Question (Baltimore: Helicon, 1960); Joseph C. McKenna, “Ethics and War,” American Political Science Review 54 (September 1960), 647-658; Robert W. Tucker, The Just War: A Study in Contemporary American Doctrine (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1960); G. E. M. Anscombe and Walter Stein, Nuclear Weapons: A Catholic Response (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961); Paul Ramsey, War and the Christian Conscience: How Should Modern War Be Conducted Justly? (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 1961).

44 Joseph T. Mangan, “An Historical Analysis of the Principle of Double Effect,” Theological Studies 10 (1949), 41-61; John C. Ford, “The Morality of Obliteration Bombing,” Theological Studies 5, no. 3 (September 1944), 289; Robert L. Holmes, On War and Morality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989), 193-196.

45 Francis J. Connell, “A Reply,” Commonweal, September 26, 1950, 607-608.

46 F. H. Drinkwater, “War and Conscience,” Commonweal, March 2, 1951, 511-514. See also Michael De La Bedoyere, “Pacifism and the Christian Conscience,” Commonweal, December 21, 1951, 271-273; “War and Conscience,”Commonweal, January 18, 1952, 375-378.

47 Geoffrey Best, War and Law Since 1945 (New York: Clarendon), 115-6, 204-5; conference minutes, July 7, 1949, 514.2, Central Decimal Files 1945-1949, RG 59, NA; Raymund T. Yingling and Robert W. Ginnane, “The Geneva Conventions of 1949,” American Journal of International Law 46, no. 3, (July 1951), 427.

48 Paul Ruegger, “Press Conference Statement,” April 9, 1951, box 4380, 800.571, Central Decimal Files 1950-1954, RG 59, NA; New York Times, July 23, September 27, 1952; K. R. Kreps to Secretary of State, April 20, 1951, box 879, 014, Project Decimal File 1942-1954, Directorate of Plans, Office of Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations, RG 341, NA.

49 U.N. General Assembly, “Respect for Human Rights in Armed Conflicts,” Resolution 2444, December 19, 1968; Adam Roberts and Richard Guelff (eds.), Documents on the Laws of War, (Clarendon: Oxford, 1989) 415, 455.

50 For an additional example from a prominent air power booster, see Alexander De Seversky, Air Power: Key to Survival (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1950), 184-185.

51 FM 27-10, 19.

52 Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage; Nina Tannenwald, The Nuclear Taboo: The United States and the Non-Use of Nuclear Weapons since 1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007).