[First published in December 2023]

Sickening Profits:

The Global Food System’s

Poisoned Food and Toxic Wealth

by

Colin Todhunter

About the Author

Colin Todhunter is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG). In 2018, he was named a Living Peace and Justice Leader/Model by Engaging Peace Inc. in recognition of his writings.

With reference to the section on India in the author’s 2022 e-book Food, Dispossession and Dependency. Resisting the New World Order, Aruna Rodrigues, lead petitioner in the GMO mustard Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India, stated:

“Colin Todhunter at his best: this is graphic, a detailed horror tale in the making for India, an exposé on what is planned, via the farm laws, to hand over Indian sovereignty and food security to big business. There will come a time pretty soon — (not something out there but imminent, unfolding even now), when we will pay the Cargills, Ambanis, Bill Gates, Walmarts — in the absence of national buffer food stocks (an agri policy change to cash crops, the end to small-scale farmers, pushed aside by contract farming and GM crops) — we will pay them to send us food and finance borrowing from international markets to do it.”

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter I:

BlackRock’s Economic Warfare on Humanity

Chapter II:

Millions Suffer as Junk Food Corporations Rake in Global Profits

Chapter III:

Fast-Food Graveyard: Sickened for Profit

Chapter IV:

Toxic Contagion: Funds, Food and Pharma

Chapter V:

Rachel Carson and Monsanto: The Silence of Spring

Chapter VI:

From Union Carbide to Syngenta: Pouring Poison

Chapter VII:

GMOs Essential to Feed the World? Case Study India

Chapter VIII:

Food Transition: A Greenwashed Corporate Power Grab

Chapter IX:

Challenging the Ecomodernist Dystopia

Chapter X:

The Netherlands: Template for a Brave New World?

Chapter XI:

Resisting Genetically Mutilated Food and Eco-Modernism

Chapter XII:

Post-COVID Food Crisis by Design?

Introduction

This is a follow up to the author’s e-book Food, Dispossession and Dependency — Resisting the New World Order, which was originally published in February 2022 by Global Research and is hosted on the Centre for Research on Globalization’s [CRG] website.

That book set out some key trends affecting food and agriculture, including the prevailing model of industrial, chemical-intensive farming and its deleterious impacts. Alternatives to that model were discussed, specifically agroecology. The book also looked at the farmers’ struggle in India and how the COVID-19 ‘pandemic’ was being used to manage a crisis of capitalism and the restructuring of much of the global economy, including food and agriculture.

This new e-book begins by examining how the modern food system is being shaped by the capitalist imperative for profit, with specific focus on the situation in Ukraine, and discusses the role of the world’s most powerful investment management firm, BlackRock. It then goes on to describe how people (not least children) are being sickened by corporations and a system that thrives on the promotion of ‘junk’ (ultra-processed) food laced with harmful chemicals and the use of toxic agrochemicals.

It’s a highly profitable situation for investment firms like BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity and Capital Group and the food conglomerates they invest in. But BlackRock and others are not just heavily invested in the food industry. They also profit from illnesses and diseases resulting from the food system by having stakes in the pharmaceuticals sector as well. A win-win situation.

The book goes on to describe how lobbying by agri-food corporations and their well-placed, well-funded front groups ensures this situation prevails. They continue to capture policy-making and regulatory space at international and national levels and promote the notion that without their products the world would starve.

Moreover, they are now pushing a fake-green, ecomodernist narrative in an attempt to roll out their new proprietary technologies in order to further entrench their grip on a global food system that produces poor food, illness, environmental degradation, the eradication of smallholder farming, the undermining of rural communities, dependency and dispossession.

The final chapter looks at the broader geopolitical aspects of food and agriculture in a post-COVID world characterised by food inflation, hardship and multi-trillion-dollar global debt.

Modern Food System

The prevailing globalised agrifood model is built on unjust trade policies, the leveraging of sovereign debt to benefit powerful interests, population displacement and land dispossession. It fuels export-oriented commodity monocropping and food insecurity as well as soil and environmental degradation.

This model is responsible for increasing rates of illness, nutrient-deficient diets, a narrowing of the range of food crops, water shortages, chemical runoffs, increasing levels of farmer indebtedness and the eradication of biodiversity.

It relies on a policy paradigm that privileges urbanisation, global markets, long supply chains, external proprietary inputs, highly processed food and market (corporate) dependency at the expense of rural communities, small independent enterprises and smallholder farms, local markets, short supply chains, on-farm resources, diverse agroecological cropping, nutrient dense diets and food sovereignty.

There are huge environmental, social and health issues that stem from how much of our food is currently produced and consumed. A paradigm shift is required.

The second edition of the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) took place in July 2023. The UNFSS has claimed that it aims to deliver the latest evidence-based, scientific approaches from around the world, launch a set of fresh commitments through coalitions of action and mobilise new financing and partnerships. These ‘coalitions of action’ revolve around implementing a ‘food transition’ that is more sustainable, efficient and environmentally friendly.

Founded on a partnership between the United Nations (UN) and the World Economic Forum (WEF), the UNFSS is, however, disproportionately influenced by corporate actors, lacks transparency and accountability and diverts energy and financial resources away from the real solutions needed to tackle the multiple hunger, environmental and health crises.

According to an article on The Canary website, key multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) appearing at the 2023 summit included the WEF, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, EAT (EAT Forum, EAT Foundation and EAT-Lancet Commission on Sustainable Healthy Food Systems), the World Business Council on Sustainable Development and the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.

The global corporate agrifood sector, including Coca-Cola, Danone, Kelloggs, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Tyson Foods, Unilever, Bayer and Syngenta, were also out in force along with Dutch Rabobank, the Mastercard Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Through its ‘strategic partnership’ with the UN, the WEF regards MSIs as key to achieving its vision of a ‘great reset’ — in this case, a food transition. The summit comprises a powerful alliance of global corporations, influential foundations and rich countries that are attempting to capture the narrative of ‘food systems transformation’. These interests aim to secure greater corporate concentration and agribusiness leverage over public institutions.

The UN is knowingly giving the very corporations sponsoring the current deleterious food system prime seats at the table. It is precisely these corporations who already shape the state of the global food regime. The solutions cannot be found in the corporate capitalist system that manufactured the problems described.

Challenging Corporate Power

During a press conference in July 2023, representatives from the People’s Autonomous Response to the UNFSS highlighted the urgent, coordinated actions required to address global food-related issues. The response came in the form of a statement from those representing food justice movements, small-scale food producer organisations and indigenous peoples.

The statement denounced the United Nations’ approach. Saúl Vicente from the International Indian Treaty Council said that the summit’s organisers aimed to sell their corporate and industrial project as ‘transformation’.

The movements and organisations opposing the summit called for a rapid shift away from corporate-driven industrial models towards biodiverse, agroecological, community-led food systems that prioritise the public interest over profit making. This entails guaranteeing the rights of peoples to access and control land and productive resources while promoting agroecological production and peasant seeds.

The response to the summit added that, despite the increasing recognition that industrial food systems are failing on so many fronts, agribusiness and food corporations continue to try to maintain their control. They are deploying digitalisation, artificial intelligence and other information and communication technologies to promote a new wave of farmer dependency or displacement, resource grabbing, wealth extraction and labour exploitation and to re-structure food systems towards a greater concentration of power and ever more globalised value chains.

Shalmali Guttal, from Focus on the Global South, said that people from all over the world have presented concrete, effective strategies based on food sovereignty, agroecology, the revitalisation of biodiversity and territorial markets and a solidarity-based economy. The evidence is overwhelming — the solutions devised by small-scale food producers not only feed the world but also advance gender, social, economic justice, youth empowerment, workers’ rights and real resilience to crises.

However, the UN has climbed into bed with the elitist, unaccountable WEF, corporate agrifood and big data giants, which have no time for democratic governance.

A report by FIAN International was released in parallel to the statement from the People’s Autonomous Response. The report — Food Systems Transformation – In which direction? — calls for an urgent overhaul of the global food governance architecture to guarantee decision making that prioritises the public good and the right to food for all.

Sofia Monsalve, secretary general of FIAN International, says:

“The main stumbling block for taking effective action towards more resilient, diversified, localized and agroecological food systems are the economic interests of those who advance and benefit from corporate-driven industrial food systems.”

These interests are promoting multi-stakeholderism: a process that involves corporations and their front groups and armies of lobbyists co-opting public bodies to act on their behalf in the name of ‘feeding the world’ and ‘sustainability’.

A process that places powerful private interests in the driving seat, steering policy makers to facilitate corporate needs while sidelining the strong concerns and solutions being forwarded by many civil society, small-scale food producers’ and workers’ organisations and indigenous peoples as well as prominent academics.

The very corporations that are responsible for the problems of the prevailing food system. They offer more of the same, this time packaged in a biosynthetic, genetically engineered, bug-eating, ecomodernist, fake-green wrapping.

While more than 800 million people go to bed hungry under the current food regime, these corporations and their wealthy investors continue to hunger for ever more profit and control. The economic system ensures they are not driven by food justice or any kind of justice. They are compelled to maximise profit, not least, for instance, by assigning an economic market value to all aspects of nature and social practices, whether knowledge, land, data, water, seeds or systems of resource exchange.

By cleverly (and cynically) ensuring that the needs of global markets (that is, the needs of corporate supply chains and their profit-seeking strategies) have become synonymous with the needs of modern agriculture, these corporations have secured a self-serving hegemonic policy paradigm among decision makers that is deeply embedded.

It is for good reason that the People’s Autonomous Response to the UNFSS calls for a mass mobilisation to challenge the power that major corporate interests wield:

“[This power] must be dismantled so that the common good is privileged before corporate interests. It is time to connect our struggles and fight together for a better world based on mutual respect, social justice, equity, solidarity and harmony with our Mother Earth.”

This may seem like a tall order, especially given the financialization of the food and agriculture sector, which has developed in tandem with the neoliberal agenda and the overall financialization of the global economy. It means that extremely powerful firms like BlackRock — which hold shares in a number of the world’s largest food and agribusiness companies — have a lot riding on further entrenching the existing system.

But there is hope. In 2021, the ETC Group and the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems released the report A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045. It calls for grassroots organisations, international NGOs, farmers’ and fishers’ groups, cooperatives and unions to collaborate more closely to transform financial flows and food systems from the ground up.

The report’s lead author, Pat Mooney, says that civil society can fight back and develop healthy and equitable agroecological production systems, build short (community-based) supply chains and restructure and democratise governance structures.

Chapter I:

BlackRock’s Economic Warfare on Humanity

Why is much modern food of inferior quality? Why is health suffering and smallholder farmers who feed most of the world being forced out of agriculture?

Mainly because of the mindset of the likes of Larry Fink of BlackRock — the world’s biggest asset management firm — and the economic system they profit from and promote.

Image: Larry Fink

In 2011, Fink said agricultural and water investments would be the best performers over the next 10 years.

Fink Stated:

“Go long agriculture and water and go to the beach.”

Unsurprisingly then, just three years later, in 2014, the Oakland Institute found that institutional investors, including hedge funds, private equity and pension funds, were capitalising on global farmland as a new and highly desirable asset class.

Funds tend to invest for a 10-15-year period, resulting in good returns for investors but often cause long-term environmental and social devastation. They undermine local and regional food security through buying up land and entrenching an industrial, export-oriented model of agriculture.

In September 2020, Grain.org showed that private equity funds — pools of money that use pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowment funds and investments from governments, banks, insurance companies and high net worth individuals — were being injected into the agriculture sector throughout the world.

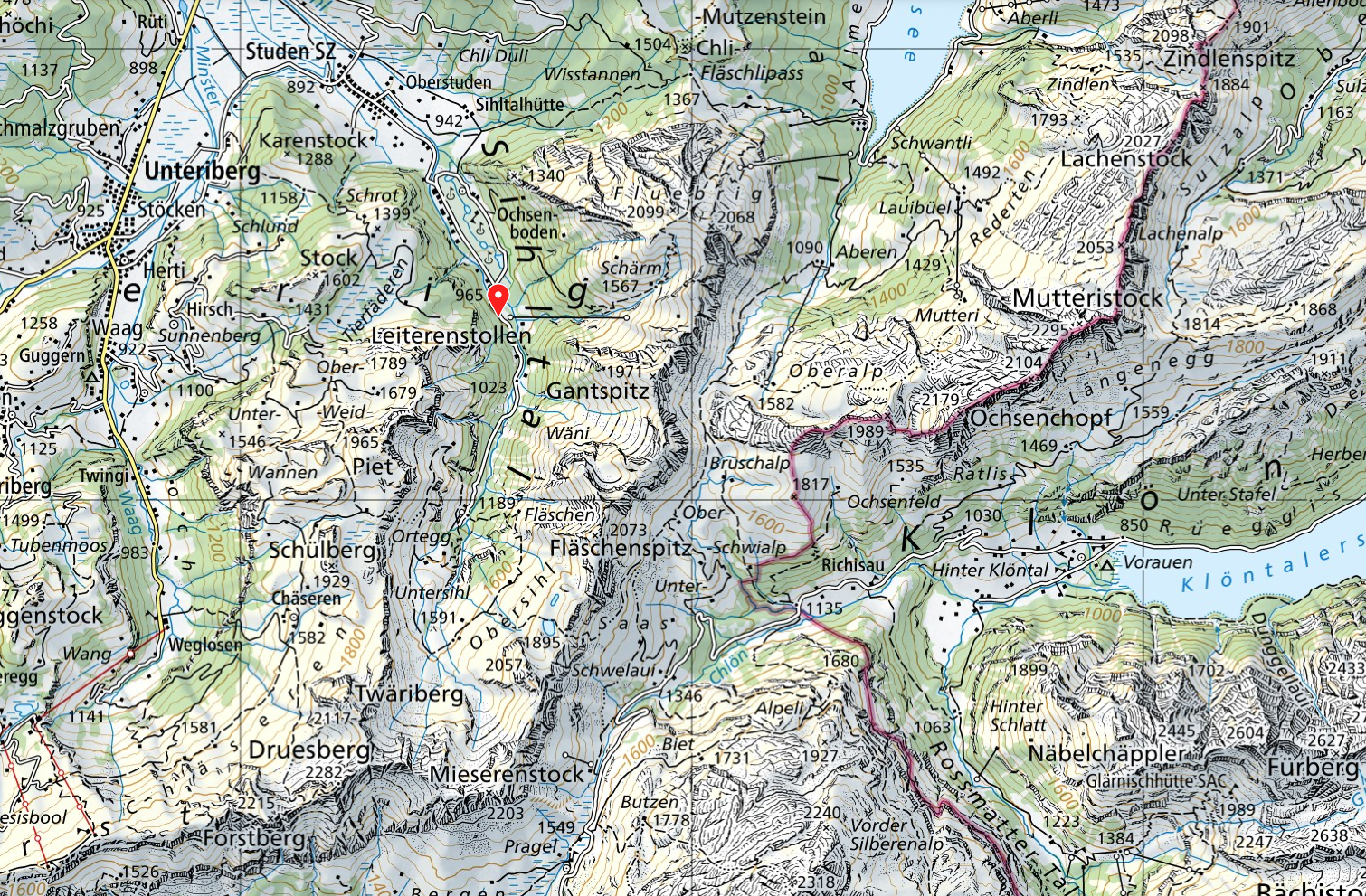

This money was being used to lease or buy up farms on the cheap and aggregate them into large-scale, US-style grain and soybean concerns. Offshore tax havens and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development had targeted Ukraine in particular.

Plundering Ukraine

Western agribusiness had been coveting Ukraine’s agriculture sector for quite some time. That country contains one third of all arable land in Europe. A 2015 article by Oriental Review noted that, since the mid-90s, Ukrainian-Americans at the helm of the US-Ukraine Business Council have been instrumental in encouraging the foreign control of Ukrainian agriculture.

In November 2013, the Ukrainian Agrarian Confederation drafted a legal amendment that would benefit global agribusiness producers by allowing the widespread use of genetically modified (GM) seeds.

Even before the conflict in the country, the World Bank incorporated measures relating to the sale of public agricultural land as conditions in a $350 million Development Policy Loan (COVID ‘relief package’) to Ukraine. This included a required ‘prior action’ to “enable the sale of agricultural land and the use of land as collateral.”

Professor Olena Borodina of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine says:

“Today, thousands of rural boys and girls, farmers, are fighting and dying in the war. They have lost everything. The processes of free land sale and purchase are increasingly liberalised and advertised. This really threatens the rights of Ukrainians to their land, for which they give their lives.”

Borodina is quoted in the February 2023 report by the Oakland Institute War and Theft: The Takeover of Ukraine’s Agricultural Land, which reveals how oligarchs and financial interests are expanding control over Ukraine’s agricultural land with help and financing from Western financial institutions.

Aid provided to Ukraine in recent years has been tied to a drastic structural adjustment programme requiring the creation of a land market through a law that leads to greater concentration of land in the hands of powerful interests. The programme also includes austerity measures, cuts in social safety nets and the privatisation of key sectors of the economy.

Frédéric Mousseau, co-author of the report, says:

“Despite being at the centre of news cycle and international policy, little attention has gone to the core of the conflict — who controls the agricultural land in the country known as the breadbasket of Europe. [The] Answer to this question is paramount to understanding the major stakes in the war.”

The report shows the total amount of land controlled by oligarchs, corrupt individuals and large agribusinesses is over nine million hectares — exceeding 28 per cent of Ukraine’s arable land (the rest is used by over eight million Ukrainian farmers).

The largest landholders are a mix of Ukrainian oligarchs and foreign interests — mostly European and North American as well as the sovereign fund of Saudi Arabia. A number of large US pension funds, foundations and university endowments are also invested in Ukrainian land through NCH Capital — a US-based private equity fund, which is the fifth largest landholder in the country.

President Zelenskyy put land reform into law in 2020 against the will of the vast majority of the population who feared it would exacerbate corruption and reinforce control by powerful interests in the agricultural sector.

The Oakland Institute notes that, while large landholders are securing massive financing from Western financial institutions, Ukrainian farmers — essential for ensuring domestic food supply — receive virtually no support. With a land market in place, amid high economic stress and war, this difference of treatment will lead to more land consolidation by large agribusinesses.

All but one of the 10 largest landholding firms are registered overseas, mainly in tax havens such as Cyprus or Luxembourg. The report identifies many prominent investors, including Vanguard Group, Kopernik Global Investors, BNP Asset Management Holding, Goldman Sachs-owned NN Investment Partners Holdings and Norges Bank Investment Management, which manages Norway’s sovereign wealth fund.

Most of the agribusiness firms are substantially indebted to Western financial institutions, in particular the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the European Investment Bank, and the International Finance Corporation — the private sector arm of the World Bank.

Together, these institutions have been major lenders to Ukrainian agribusinesses, with close to US$1.7 billion lent to just six of Ukraine’s largest landholding firms in recent years. Other key lenders are a mix of mainly European and North American financial institutions, both public and private.

The report notes that this gives creditors financial stakes in the operation of the agribusinesses and confers significant leverage over them. Meanwhile, Ukrainian farmers have had to operate with limited amounts of land and financing, and many are now on the verge of poverty.

According to the Oakland Institute, small-scale farmers in Ukraine demonstrate resilience and enormous potential for leading the expansion of a different production model based on agroecology and producing healthy food. Whereas large agribusinesses are geared towards export markets, it is Ukraine’s small and medium-sized farmers who guarantee the country’s food security.

This is underlined by the State Statistics Service of Ukraine in its report ‘Main agricultural characteristics of households in rural areas in 2011’, which showed that smallholder farmers in Ukraine operate 16 per cent of agricultural land, but provide 55 per cent of agricultural output, including 97 per cent of potatoes, 97 per cent of honey, 88 per cent of vegetables, 83 per cent of fruits and berries and 80 per cent of milk.

The Oakland Institute states:

“Ukraine is now the world’s third-largest debtor to the International Monetary Fund and its crippling debt burden will likely result in additional pressure from its creditors, bondholders and international financial institutions on how post-war reconstruction — estimated to cost US$750 billion — should happen.”

Financial institutions are leveraging Ukraine’s crippling debt to drive further privatisation and liberalisation — backing the country into a corner to make it an offer it can’t refuse.

An airman loads weapons cargo bound for Ukraine onto a C-17 Globemaster III during a security assistance mission at Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, Sept. 14, 2022. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Marco A. Gomez)

Since the war began, the Ukrainian flag has been raised outside parliament buildings in the West and iconic landmarks have been lit up in its colours. An image bite used to conjure up feelings of solidarity and support for that nation while serving to distract from the harsh machinations of geopolitics and modern-day economic plunder that is unhindered by national borders and has scant regard for the plight of ordinary citizens.

It is interesting to note that Larry Fink and BlackRock are to ‘coordinate’ investment in ‘rebuilding’ Ukraine.

An official statement released in late December 2022 said the agreement with BlackRock would:

“… focus in the near term on coordinating the efforts of all potential investors and participants in the reconstruction of our country, channelling investment into the most relevant and impactful sectors of the Ukrainian economy.”

According to the Code Pink organisation, BlackRock has $5.7 billion invested in Boeing, $2 billion in General Dynamics; $4.6 billion in Lockheed Martin; $2.6 billion in Northrop Grumman; and $6 billion in Raytheon. It profits from both destruction and reconstruction.

Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022, billions of dollars’ worth of military hardware have been sent to Ukraine by the EU. By late February 2023, it had forwarded €3.6 billion worth of military assistance to the Zelensky regime via the European Peace Fund. However, even at that time, the total cost for EU countries could have been closer to €6.9 billion.

In late June 2023, the European Union (EU) pledged a further €3.5 billion in military aid.

Great news for European and UK armaments companies like BAE Systems, Saab and Rheinmetall, which are raking in huge profits from the destruction of Ukraine (see the CNN Business report Europe’s arms spending on Ukraine boosts defense companies).

US arms manufacturers like Raytheon and Lockheed Martin are also acquiring multi-billion-dollar contracts (as outlined in the online articles Raytheon wins $1.2 billion surface-to-air missile order for Ukraine and Pentagon readies new $2 billion Ukraine air defense package including missiles).

Meanwhile, away from the boardrooms, business conferences and high-level strategizing, hundreds of thousands of ordinary young Ukrainians have died.

Irish Members of the European Parliament Mick Wallace and Clare Daly have been staunch critics of the EU stance on Ukraine (see Clare Daly talking in the EU parliament about Ukraine burning through a generation of men on YouTube).

Wallace addressed the EU Parliament in June 2023, describing the heist currently taking place in that country by Western corporations.

Wallace said:

“The damage to Ukraine is devastating. Towns and cities that endured for hundreds of years don’t exist anymore. We must recognise that these towns, cities and surrounding lands were long being stolen by local oligarchs colluding with global financial capital. This theft quickened with the onset of the war in 2014.

“The pro-Western government opened the doors wide for massive structural adjustment and privatisation programmes spearheaded by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Zelensky used the current war to concentrate power and accelerate the corporate fire sale. He banned opposition parties that were resisting deeply unpopular reforms to the laws restricting the sale of land to foreign investors.

“Over three million hectares of agricultural land are now owned by companies based in Western tax havens. Ukraine’s mineral deposits alone are worth over $12 trillion. Western companies are licking their lips.

“What are the working-class people of Ukraine dying for?”

Hard-edged Rock

BlackRock is a publicly owned investment manager that primarily provides its services to institutional, intermediary and individual investors. The firm exists to put its assets to work to make money for its clients. And it must ensure the financial system functions to secure this goal. And this is exactly what it does.

Back in 2010, the farmlandgrab.org website reported that BlackRock’s global agriculture fund would target (invest in) companies involved with agriculture-related chemical products, equipment and infrastructure, as well as soft commodities and food, biofuels, forestry, agricultural sciences and arable land.

According to research by Global Witness, it has since indirectly profited from human rights and environmental abuses through investing in banks notorious for financing harmful palm oil firms (see the article The true price of palm oil, 2021).

Blackrock’s Global Consumer Staples exchange rated fund (ETF), which was launched in 2006 and, according to the article The rise of financial investment and common ownership in global agrifood firms (Review of International Political Economy, 2019), has:

“US$560 million in assets under management, holds shares in a number of the world’s largest food companies, with agrifood stocks making up around 75 per cent of the fund. Nestlé is the funds’ largest holding, and other agrifood firms that make up the fund include Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Walmart, Anheuser Busch InBev, Mondelez, Danone, and Kraft Heinz.”

The article also states that BlackRock’s iShares Core S&P 500 Index ETF has $150 billion in assets under management. Most of the top publicly traded food and agriculture firms are part of the S&P 500 index and BlackRock holds significant shares in those firms.

The author of the article, Professor Jennifer Clapp, also notes BlackRock’s COW Global Agriculture ETF has $231 million in assets and focuses on firms that provide inputs (seeds, chemicals and fertilizers) and farm equipment and agricultural trading companies. Among its top holdings are Deere & Co, Bunge, ADM and Tyson. This is based on BlackRock’s own data from 2018.

Jennifer Clapp states:

“Collectively, the asset management giants — BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity, and Capital Group — own significant proportions of the firms that dominate at various points along agrifood supply chains. When considered together, these five asset management firms own around 10–30 per cent of the shares of the top firms within the agrifood sector.”

BlackRock et al are heavily invested in the success of the prevailing globalised system of food and agriculture.

They profit from an inherently predatory system that — focusing on the agrifood sector alone — has been responsible for, among other things, the displacement of indigenous systems of production, the impoverishment of many farmers worldwide, the destruction of rural communities and cultures, poor-quality food and illness, less diverse diets, ecological destruction and the proletarianization of independent producers.

Due to their size, according to journalist Ernst Wolff, BlackRock and its counterpart Vanguard exert control over governments and important institutions like the European Central Bank (ECB) and the US Federal Reserve. BlackRock and Vanguard have more financial assets than the ECB and the Fed combined.

BlackRock currently has $10 trillion in assets under its management and, to underline the influence of the firm, Fink himself is a billionaire who sits on the board of the WEF and the powerful and highly influential Council for Foreign Relations, often referred to as the shadow government of the US — the real power behind the throne.

Researcher William Engdahl says that since 1988 the company has put itself in a position to de facto control the Federal Reserve, most Wall Street mega-banks, including Goldman Sachs, the Davos WEF great reset and now the Biden administration.

Engdahl describes how former top people at BlackRock are now in key government positions, running economic policy for the Biden administration, and that the firm is steering the ‘great reset’ and the global ‘green’ agenda.

Fink recently eulogised about the future of food and ‘coded’ seeds that would produce their own fertiliser. He says this is “amazing technology”. This technology is years away and whether it can deliver on what he says is another thing.

More likely, it will be a great investment opportunity that is par for the course as far as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in agriculture are concerned: a failure to deliver on its inflated false promises. And even if it does eventually deliver, a whole host of ‘hidden costs’ (health, social, ecological etc.) will probably emerge.

And that’s not idle speculation. We need look no further than previous ‘interventions’ in food/farming under the guise of Green Revolution technologies, which did little if anything to boost overall food production (in India at least, according to Professor Glenn Stone in his paper New Histories of the Green Revolution) but brought with it tremendous ecological, environmental and social costs and adverse impacts on human health, highlighted by many researchers and writers, not least in Bhaskar Save’s open letter to Indian officials and the work of Vandana Shiva.

However, the Green Revolution entrenched seed and agrichemical giants in global agriculture and ensured farmers became dependent on their proprietary inputs and global supply chains. After all, value capture was a key aim of the project.

But why should Fink care about these ‘hidden costs’, not least the health impacts?

Well, actually, he probably does — with his eye on investments in ‘healthcare’ and Big Pharma. BlackRock’s investments support and profit from industrial agriculture as well as the hidden costs.

Poor health is good for business (for example, see on the BlackRock website BlackRock on healthcare investment opportunities amid Covid-19). Scroll through BlackRock’s website and it soon becomes clear that it sees the healthcare sector as a strong long-term bet.

And for good reason. For instance, increased consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) was associated with more than 10 per cent of all-cause premature, preventable deaths in Brazil in 2019 according to a peer-reviewed study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The findings are significant not only for Brazil but more so for high income countries such as the US, Canada, the UK and Australia, where UPFs account for more than half of total calorific intake. Brazilians consume far less of these products than countries with high incomes. This means the estimated impact would be even higher in richer nations.

Due to corporate influence over trade deals, governments and the World Trade Organization (WTO), transnational food retail and food processing companies continue to colonise markets around the world and push UPFs.

In Mexico, global agrifood companies have taken over food distribution channels, replacing local foods with cheap processed items. In Europe, more than half the population of the European Union is overweight or obese, with the poor especially reliant on high-calorie, poor nutrient quality food items.

Larry Fink is good at what he does — securing returns for the assets his company holds. He needs to keep expanding into or creating new markets to ensure the accumulation of capital to offset the tendency for the general rate of profit to fall. He needs to accumulate capital (wealth) to be able to reinvest it and make further profits.

When capital struggles to make sufficient profit, productive wealth (capital) over accumulates, devalues and the system goes into crisis. To avoid crisis, capitalism requires constant growth, expanding markets and sufficient demand.

And that means laying the political and legislative groundwork to facilitate this. In India, for example, the now-repealed three farm laws of 2020 would have provided huge investment opportunities for the likes of BlackRock. These three laws — imperialism in all but name — represented a capitulation to the needs of foreign agribusiness and asset managers who require access to India’s farmland.

The laws would have sounded a neoliberal death knell for India’s food sovereignty, jeopardised its food security and destroyed tens of millions of livelihoods. But what matters to global agricapital and investment firms is facilitating profit and maximising returns on investment.

This has been a key driving force behind the modern food system that sees around a billion people experiencing malnutrition in a world of food abundance. That is not by accident but by design — inherent to a system that privileges corporate profit ahead of human need.

The modern agritech/agribusiness sector uses notions of it and its products being essential to ‘feed the world’ by employing ‘amazing technology’ in an attempt to seek legitimacy. But the reality is an inherently unjust globalised food system, farmers forced out of farming or trapped on proprietary product treadmills working for corporate supply chains and the public fed GMOs, more ultra-processed products and lab-engineered food.

A system that facilitates ‘going long and going to the beach’ serves elite interests well. For vast swathes of humanity, however, economic warfare is waged on them every day courtesy of a hard-edged (black) rock.

Chapter II:

Millions Suffer as Junk Food Corporations Rake in Global Profits

As mentioned in the previous chapter, increased consumption of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) was associated with more than 10 per cent of all-cause premature, preventable deaths in Brazil in 2019. That is the finding of a peer-reviewed study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

UPFs are ready-to-eat-or-heat industrial formulations made with ingredients extracted from foods or synthesised in laboratories. These have gradually been replacing traditional foods and meals made from fresh and minimally processed ingredients in many countries.

The study found that approximately 57,000 deaths in one year could be attributed to the consumption of UPFs — 10.5 per cent of all premature deaths and 21.8 [per cent of all deaths from preventable noncommunicable diseases in adults aged 30 to 69.

The study’s lead investigator Eduardo AF Nilson states:

“To our knowledge, no study to date has estimated the potential impact of UPFs on premature deaths.”

Across all age groups and sex strata, consumption of UPFs ranged from 13 per cent to 21 per cent of total food intake in Brazil during the period studied.

UPFs have steadily replaced the consumption of traditional whole foods, such as rice and beans, in Brazil.

Reducing consumption of UPFs by 10 to 50 per cent could potentially prevent approximately 5,900 to 29,300 premature deaths in Brazil each year. Based on this, hundreds of thousands of premature deaths could be prevented globally annually. And many millions more could be prevented from acquiring long-term, debilitating conditions.

Nilson adds:

“Consumption of UPFs is associated with many disease outcomes, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, some cancers and other diseases, and it represents a significant cause of preventable and premature deaths among Brazilian adults.”

Examples of UPFs are prepackaged soups, sauces, frozen pizza, ready-to-eat meals, hot dogs, sausages, sodas, ice cream, and store-bought cookies, cakes, candies and doughnuts.

And yet, due to trade deals, government support and WTO influence, transnational food retail and food processing companies continue to colonise markets around the world and push UPFs.

In Mexico, for instance, these companies have taken over food distribution channels, replacing local foods with cheap processed items, often with the direct support of the government. Free trade and investment agreements have been critical to this process and the consequences for public health have been catastrophic.

Mexico’s National Institute for Public Health released the results of a national survey of food security and nutrition in 2012. Between 1988 and 2012, the proportion of overweight women between the ages of 20 and 49 increased from 25 to 35 per cent and the number of obese women in this age group increased from 9 to 37 per cent. Some 29 per cent of Mexican children between the ages of 5 and 11 were found to be overweight, as were 35 per cent of the youngsters between 11 and 19, while one in 10 school age children experienced anaemia.

The North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) led to the direct investment in food processing and a change in Mexico’s retail structure (towards supermarkets and convenience stores) as well as the emergence of global agribusiness and transnational food companies in the country.

NAFTA eliminated rules preventing foreign investors from owning more than 49 per cent of a company. It also prohibited minimum amounts of domestic content in production and increased rights for foreign investors to retain profits and returns from initial investments.

By 1999, US companies had invested 5.3 billion dollars in Mexico’s food processing industry, a 25-fold increase in just 12 years.

US food corporations also began to colonise the dominant food distribution networks of small-scale vendors, known as tiendas (corner shops). This helped spread nutritionally poor food as they allowed these corporations to sell and promote their foods to poorer populations in small towns and communities. By 2012, retail chains had displaced tiendas as Mexico’s main source of food sales.

A Spoonful of Deceit

Turning to Europe, more than half the population of the European Union (EU) is overweight or obese. Without effective action, this number will grow substantially by 2026.

That warning was issued in 2016 and was based on the report A Spoonful of Sugar: How the Food Lobby Fights Sugar Regulation in the EU by the research and campaign group Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO).

CEO noted that obesity rates were rising fastest among lowest socio-economic groups. That is because energy-dense foods of poor nutritional value are cheaper than more nutritious foods, such as vegetables and fruit, and relatively poor families with children purchase food primarily to satisfy their hunger.

The report argued that more people than ever before are eating processed foods as a large part of their diet. And the easiest way to make industrial, processed food cheap, long-lasting and enhance the taste is to add extra sugar as well as salt and fat to products.

In the United Kingdom, the cost of obesity was estimated at £27 billion per year in 2016, and approximately 7 per cent of national health spending in EU member states as a whole is due to obesity in adults.

The food industry has vigorously mobilised to stop vital public health legislation in this area by pushing free trade agreements and deregulation drives, exercising undue influence over regulatory bodies, capturing scientific expertise, championing weak voluntary schemes and outmanoeuvring consumer groups by spending billions on aggressive lobbying.

The leverage which food industry giants have over EU decision-making has helped the sugar lobby to see off many of the threats to its profit margins.

CEO argued that key trade associations, companies and lobby groups related to sugary food and drinks together spend an estimated €21.3 million (2016) annually to lobby the EU.

While industry-funded studies influence European Food Standards Authority decisions, Coca Cola, Nestlé and other food giants engage in corporate propaganda by sponsoring sporting events and major exercise programmes to divert attention from the impacts of their products and give the false impression that exercise and lifestyle choices are the major factors in preventing poor health.

Katharine Ainger, freelance journalist and co-author of CEO’s report, said:

“Sound scientific advice is being sidelined by the billions of euros backing the sugar lobby. In its dishonesty and its disregard for people’s health, the food and drink industry rivals the tactics we’ve seen from the tobacco lobby for decades.”

ILSI Industry Front Group

One of the best-known industry front groups with global influence is what a September 2019 report in the New York Times (NYT) called a “shadowy industry group” — the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI).

The institute was founded in 1978 by Alex Malaspina, a Coca-Cola scientific and regulatory affairs leader. It started with an endowment of $22 million with the support of Coca Cola.

Since then, ILSI has been quietly infiltrating government health and nutrition bodies around the globe and has more than 17 branches that influence food safety and nutrition science in various regions.

Little more than a front group for its 400 corporate members that provide its $17 million budget, ILSI’s members include Coca-Cola, DuPont, PepsiCo, General Mills and Danone.

The NYT says ILSI has received more than $2 million from chemical companies, among them Monsanto. In 2016, a UN committee issued a ruling that glyphosate, the key ingredient in Monsanto’s weedkiller Roundup, was “probably not carcinogenic,” contradicting an earlier report by the WHO’s cancer agency. The committee was led by two ILSI officials.

From India to China, whether it has involved warning labels on unhealthy packaged food or shaping anti-obesity education campaigns that stress physical activity and divert attention from the food system itself, prominent figures with close ties to the corridors of power have been co-opted to influence policy in order to boost the interests of agri-food corporations.

As far back as 2003, it was reported by The Guardian newspaper that ILSI had spread its influence across the national and global food policy arena. The report talked about undue influence exerted on specific WHO/FAO food policies dealing with dietary guidelines, pesticide use, additives, trans-fatty acids and sugar.

In January 2019, two papers by Harvard Professor Susan Greenhalgh, in the BMJ and the Journal of Public Health Policy, revealed ILSI’s influence on the Chinese government regarding issues related to obesity. And in April 2019, Corporate Accountability released a report on ILSI titled Partnership for an Unhealthy Planet.

A 2017 report in the Times of India noted that ILSI-India was being actively consulted by India’s apex policy-formulating body — Niti Aayog. ILSI-India’s board of trustees was dominated by food and beverage companies — seven of 13 members were from the industry or linked to it (Mondelez, Mars, Abbott, Ajinomoto, Hindustan Unilever and Nestle) and the treasurer was Sunil Adsule of Coca-Cola India.

In India, ILSI’s expanding influence coincides with mounting rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

In 2020, US Right to Know (USRTK) referred to a study published in Public Health Nutrition that helped to further confirm ILSI as little more than an industry propaganda arm.

The study, based on documents obtained by USRTK, uncovered “a pattern of activity in which ILSI sought to exploit the credibility of scientists and academics to bolster industry positions and promote industry-devised content in its meetings, journal, and other activities.”

Gary Ruskin, executive director of USRTK, a consumer and public health group, said:

“ILSI is insidious… Across the world, ILSI is central to the food industry’s product defence, to keep consumers buying the ultra-processed food, sugary beverages and other junk food that promotes obesity, type 2 diabetes and other ills.”

The study also revealed new details about which companies fund ILSI and its branches.

ILSI North America’s draft 2016 IRS form 990 shows a $317,827 contribution from PepsiCo, contributions greater than $200,000 from Mars, Coca-Cola and Mondelez and contributions greater than $100,000 from General Mills, Nestle, Kellogg, Hershey, Kraft, Dr Pepper Snapple Group, Starbucks Coffee, Cargill, Unilever and Campbell Soup.

ILSI’s draft 2013 Internal Revenue Service form 990 shows that it received $337,000 from Coca-Cola, and more than $100,000 each from Monsanto, Syngenta, Dow AgroSciences, Pioneer Hi-Bred, Bayer Crop Science and BASF.

Global institutions, like the WTO, and governments continue to act as the administrative arm of industry, boosting corporate profits while destroying public health and cutting short human life.

Part of the solution lies in challenging a policy agenda that privileges global markets, highly processed food and the needs of ‘the modern food system’ — meaning the bottom line of dominant industrial food conglomerates.

It also involves protecting and strengthening local markets, short supply chains and independent small-scale enterprises, including traditional food processing concerns and small retailers.

And, of course, we need to protect and strengthen agroecological, smallholder farming that bolsters nutrient-dense diets — more family farms and healthy food instead of more disease and allopathic family doctors.

Chapter III:

Fast-Food Graveyard: Sickened for Profit

The modern food system is responsible for making swathes of humanity ill, causing unnecessary suffering and sending many people to an early grave. It is part of a grotesque food-pharma conveyor belt that results in massive profits for the dominant agrifood and pharmaceuticals corporations.

Much of the modern food system has been shaped by big agribusiness concerns like Monsanto (now Bayer) and Cargill, giant food companies like Nestle, Pepsico and Kellog’s and, more recently, institutional investors like BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street.

For the likes of BlackRock, which invests in both food and pharma, fuelling a system increasingly based on ultra processed food (UPF) with its cheap and unhealthy ingredients is a sure-fire money spinner.

Toxic Junk

Consider that fast food is consumed by 85 million US citizens each day. Several chains are the primary suppliers of many school lunches. Some 30 million school meals are served to children each day. For millions of underprivileged children in the US, these meals are their only access to nutrition.

In 2022, Moms Across America (MAA) and Children’s Health Defense (CHD) commissioned the testing of school lunches and found that 5.3 per cent contained carcinogenic, endocrine-disrupting and liver disease-causing glyphosate; 74 per cent contained at least one of 29 harmful pesticides; four veterinary drugs and hormones were found in nine of the 43 meals tested; and all of the lunches contained heavy metals at levels up to 6,293 times higher than the US Environmental Protection Agency’s maximum levels allowed in drinking water. Moreover, the majority of the meals were abysmally low in nutrients.

As a follow up, MAA, a non-profit organisation, with support from CHD and the Centner Academy, decided to have the top 10 most popular fast-food brand meals extensively tested for 104 of the most commonly used veterinary drugs and hormones.

The Health Research Institute tested 42 fast-food meals from 21 locations nationwide. The top 10 brands tested were McDonald’s, Starbucks, Chick-fil-A, TacoBell, Wendy’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Burger King, Subway, Domino’s and Chipotle.

Collectively, these companies’ annual gross sales are $134,308,000,000.

Three veterinary drugs and hormones were found in 10 fast-food samples tested. One sample from Chick-fil-A contained a contraceptive and antiparasitic called Nicarbazin, which has been prohibited.

Some 60 per cent of the samples contained the antibiotic Monesin, which is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for human use and has been shown to cause severe harm when consumed by humans.

And 40 per cent contained the antibiotic Narasin. MAA says that animal studies show this substance causes anorexia, diarrhoea, dyspnea, depression, ataxia, recumbency and death, among other things.

Monensin and Narasin are antibiotic ionophores, toxic to horses and dogs at extremely low levels, leaving their hind legs dysfunctional. Ionophores cause weight gain in beef and dairy cattle and are therefore widely used but also “cause acute cardiac rhabdomyocyte degeneration and necrosis”, according to a 2017 paper published in Reproductive and Developmental Toxicology (Second Edition).

For many years, ionophores have also been used to control coccidiosis in poultry. However, misuse of ionophores can cause toxicity with significant clinical symptoms. Studies show that ionophore toxicity mainly affects myocardial and skeletal muscle cells.

Only Chipotle and Subway had no detectable levels of veterinary drugs and hormones.

Following these findings, MAA expressed grave concern about the dangers faced by people, especially children, who are unknowingly eating unprescribed antibiotic ionophores. The non-profit asks: are the side effects of these ionophores in dogs and horses, leaving their hind legs dysfunctional, related to millions of US citizens presenting with restless leg syndrome and neuropathy? These conditions were unknown in most humans just a generation or two ago.

A concerning contraceptive (for geese and pigeons), an antiparasitic called Nicarbazin, prohibited after many years of use, was found in Chick fil-A sandwich samples.

The executive director of MAA, Zen Honeycutt, concludes:

“The impact on millions of Americans, especially children and young adults, consuming a known animal contraceptive daily is concerning. With infertility problems on the rise, the reproductive health of this generation is front and center for us, in light of these results.”

MAA says that it is not uncommon for millions of US citizens to consume fast food for breakfast, lunch or dinner, or all three meals, every day. School lunches are often provided by fast-food suppliers and typically are the only meals underprivileged children receive and a major component of the food consumed by most children.

Exposure to hormones from consuming concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) livestock could be linked to the early onset of puberty, miscarriages, increasing incidence of twin births and reproductive problems. These hormones have been linked to cancers, such as breast and uterine, reproductive issues and developmental problems in children.

So, how can it be that food — something that is supposed to nourish and sustain life — has now become so toxic?

Corporate Influence

As already noted with ILSI, the answer lies in the influence of a relative handful of food conglomerates, which shape food policy and dominate the market.

For instance, recent studies have linked UPFs such as ice-cream, fizzy drinks and ready meals to poor health, including an increased risk of cancer, weight gain and heart disease. Global consumption of the products is soaring and UPFs now make up more than half the average diet in the UK and US.

In late September 2023, however, a media briefing in London suggested consumers should not be too concerned about UPFs. After the event, The Guardian newspaper reported that three out of five scientists on the expert panel for the briefing who suggested UPFs are being unfairly demonised had ties to the world’s largest manufacturers of the products.

The briefing generated various positive media headlines on UPFs, including “Ultra-processed foods as good as homemade fare, say experts” and “Ultra-processed foods can sometimes be better for you, experts claim.”

It was reported by The Guardian that three of the five scientific experts on the panel had either received financial support for research from UPF manufacturers or hold key positions with organisations that are funded by them. The manufacturers include Nestlé, Mondelēz, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Unilever and General Mills.

Professor Janet Cade (University of Leeds) told the briefing that most research suggesting a link between UPFs and poor health cannot show cause and effect, adding that processing can help to preserve nutrients. Cade is the chair of the advisory committee of the British Nutrition Foundation, whose corporate members include McDonald’s, British Sugar and Mars. It is funded by companies including Nestlé, Mondelēz and Coca-Cola.

Professor Pete Wilde (Quadram Institute) also defended UPFs, comparing then favourably with homemade items. Wilde has received support for his research from Unilever, Mondelēz and Nestlé.

Professor Ciarán Forde (Wageningen University in the Netherlands) told the briefing that advice to avoid UPF “risks demonising foods that are nutritionally beneficial”. Forde was previously employed by Nestlé and has received financial support for research from companies including PepsiCo and General Mills.

Professor Janet Cade told the media briefing in London that people rely on processed foods for a wide number of reasons; if they were removed, this would require a huge change in the food supply. She added that this would be unachievable for most people and potentially result in further stigmatisation and guilt for those who rely on processed foods, promoting further inequalities in disadvantaged groups.

While part of the solution lies in tackling poverty and reliance on junk food, the focus must also be on challenging the power wielded by a small group of food corporations and redirecting the huge subsidies poured into the agrifood system that ensure massive corporate profit while fuelling bad food, poor health and food insecurity.

A healthier food regime centred on human need rather than corporate profit is required. This would entail strengthening local markets, prioritising short supply chains from farm to fork and supporting independent smallholder organic agriculturalists (incentivised to grow a more diverse range of nutrient-dense crops) and small-scale retailers.

Saying that eradicating UPFs would result in denying the poor access to cheap, affordable food is like saying let them eat poison.

Given the scale of the problem, change cannot be achieved overnight. However, a long food movement could transform the food system, a strategy set out in a 2021 report by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems and ETC Group.

More people should be getting on board with this and promoting it at media briefings. But that might result in biting the hand that feeds.

Chapter IV:

Toxic Contagion: Funds, Food and Pharma

In 2014, the organisation GRAIN revealed that small farms produce most of the world’s food in its report Hungry for land: small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland. The report Small-scale Farmers and Peasants Still Feed the World (ETC Group, 2022) confirmed this.

Small farmers produce up to 80 per cent of the food in the non-industrialised countries. However, they are currently squeezed onto less than a quarter of the world’s farmland. The period 1974-2014 saw 140 million hectares — more than all the farmland in China — being taken over for soybean, oil palm, rapeseed and sugar cane plantations.

GRAIN noted that the concentration of fertile agricultural land in fewer and fewer hands is directly related to the increasing number of people going hungry every day. While industrial farms have enormous power, influence and resources, GRAIN’s data showed that small farms almost everywhere outperform big farms in terms of productivity.

In the same year, policy think tank the Oakland Institute released a report stating that the first years of the 21st century will be remembered for a global land rush of nearly unprecedented scale. An estimated 500 million acres, an area eight times the size of Britain, was reported bought or leased across the developing world between 2000 and 2011, often at the expense of local food security and land rights.

Institutional investors, including hedge funds, private equity, pension funds and university endowments, were eager to capitalise on global farmland as a new and highly desirable asset class.

This trend was not confined to buying up agricultural land in low-income countries. Oakland Institute’s Anuradha Mittal argued that there was a new rush for US farmland. One industry leader estimated that $10 billion in institutional capital was looking for access to this land in the US.

Although investors believed that there is roughly $1.8 trillion worth of farmland across the US, of this between $300 billion and $500 billion (2014 figures) is considered to be of “institutional quality” — a combination of factors relating to size, water access, soil quality and location that determine the investment appeal of a property.

In 2014, Mittal said that if action is not taken, then a perfect storm of global and national trends could converge to permanently shift farm ownership from family businesses to institutional investors and other consolidated corporate operations.

Why It Matters

Peasant/smallholder agriculture prioritises food production for local and national markets as well as for farmers’ own families, whereas corporations take over fertile land and prioritise commodities or export crops for profit and markets far away that tend to cater for the needs of more affluent sections of the global population.

In 2013, a UN report stated that farming in rich and poor nations alike should shift from monocultures towards greater varieties of crops, reduced use of fertilisers and other inputs, increased support for small-scale farmers and more locally focused production and consumption of food. The report stated that monoculture and industrial farming methods were not providing sufficient affordable food where it is needed.

In September 2020, however, GRAIN showed an acceleration of the trend that it had warned of six years earlier: institutional investments via private equity funds being used to lease or buy up farms on the cheap and aggregate them into industrial-scale concerns. One of the firms spearheading this is the investment asset management firm BlackRock, which exists to put its funds to work to make money for its clients.

BlackRock holds shares in a number of the world’s largest food companies, including Nestlé, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Walmart, Danone and Kraft Heinz and also has significant shares in most of the top publicly traded food and agriculture firms: those which focus on providing inputs (seeds, chemicals, fertilisers) and farm equipment as well as agricultural trading companies, such as Deere, Bunge, ADM and Tyson (based on BlackRock’s own data from 2018).

Together, the world’s top five asset managers — BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Fidelity and Capital Group — own around 10–30 per cent of the shares of the top firms in the agrifood sector.

The article Who is Driving the Destructive Industrial Agriculture Model? (2022) by Frederic Mousseau of the Oakland Institute showed that BlackRock and Vanguard are by far the biggest shareholders in eight of the largest pesticides and fertiliser companies: Yara, CF Industries Holdings K+S Aktiengesellschaft, Nutrien, The Mosaic Company, Corteva and Bayer.

These companies’ profits were projected to double, from US$19 billion in 2021 to $38 billion in 2022, and will continue to grow as long as the industrial agriculture production model on which they rely keeps expanding. Other major shareholders include investment firms, banks and pension funds from Europe and North America.

Through their capital injections, BlackRock et al fuel and make huge profits from a globalised food system that has been responsible for eradicating indigenous systems of production, expropriating seeds, land and knowledge, impoverishing, displacing or proletarianizing farmers and destroying rural communities and cultures. This has resulted in poor-quality food and illness, human rights abuses and ecological destruction.

Systemic Compulsion

Post-1945, the Rockefeller Chase Manhattan bank with the World Bank helped roll out what has become the prevailing modern-day agrifood system under the guise of a supposedly ‘miraculous’ corporate-controlled, chemical-intensive Green Revolution (its much-heralded but seldom challenged ‘miracles’ of increased food production are now being questioned; for instance, see the What the Green Revolution Did for India and New Histories of the Green Revolution).

Ever since, the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO have helped consolidate an export-oriented industrial agriculture based on Green Revolution thinking and practices. A model that uses loan conditionalities to compel nations to ‘structurally adjust’ their economies and sacrifice food self-sufficiency.

Countries are placed on commodity crop production treadmills to earn foreign currency (US dollars) to buy oil and food on the global market (benefitting global commodity traders like Cargill, which helped write the WTO trade regime — the Agreement on Agriculture), entrenching the need to increase cash crop cultivation for exports.

Today, investment financing is helping to drive and further embed this system of corporate dependency worldwide. BlackRock is ideally positioned to create the political and legislative framework to maintain this system and increase the returns from its investments in the agrifood sector.

The firm has around $10 trillion in assets under its management and has positioned itself to effectively control the US Federal Reserve, many Wall Street mega-banks and the Biden administration: a number of former top people at BlackRock are in key government positions, shaping economic policy.

So, it is no surprise that we are seeing an intensification of the lop-sided battle being waged against local markets, local communities and indigenous systems of production for the benefit of global private equity and big agribusiness.

For example, while ordinary Ukrainians are currently defending their land, financial institutions are supporting the consolidation of farmland by rich individuals and Western financial interests. It is similar in India (see the article The Kisans Are Right: Their Land Is at Stake) where a land market is being prepared and global investors are no doubt poised to swoop.

In both countries, debt and loan conditionalities on the back of economic crises are helping to push such policies through. For instance, there has been a 30+ year plan to restructure India’s economy and agriculture. This stems from the country’s 1991 foreign exchange crisis, which was used to impose IMF-World Bank debt-related ‘structural adjustment’ conditionalities. The Mumbai-based Research Unit for Political Economy locates agricultural ‘reforms’ within a broader process of Western imperialism’s increasing capture of the Indian economy.

Yet ‘imperialism’ is a dirty word never to be used in ‘polite’ circles. Such a notion is to be brushed aside as ideological by the corporations that benefit from it. Instead, what we constantly hear from these conglomerates is that countries are choosing to embrace their entry and proprietary inputs into the domestic market as well as ‘neoliberal reforms’ because these are essential if we are to feed a growing global population. The reality is that these firms and their investors are attempting to deliver a knockout blow to smallholder farmers and local enterprises in places like India.

But the claim that these corporations, their inputs and their model of agriculture is vital for ensuring global food security is a proven falsehood. However, in an age of censorship and doublespeak, truth has become the lie, and the lie is truth. Dispossession is growth, dependency is market integration, population displacement is land mobility, serving the needs of agrifood corporations is modern agriculture and the availability of adulterated, toxic food as part of a monoculture diet is called ‘feeding the world’.

And when a ‘pandemic’ was announced and those who appeared to be dying in greater numbers were the elderly and people with obesity, diabetes and cardio-vascular disease, few were willing to point the finger at the food system and its powerful corporations, practices and products that are responsible for the increasing prevalence of these conditions (see campaigner Rosemary Mason’s numerous papers documenting this on Academia.edu). Because this is the real public health crisis that has been building for decades.

But who cares? BlackRock, Vanguard and other institutional investors? Highly debatable because if we turn to the pharmaceuticals industry, we see similar patterns of ownership involving the same players.

A December 2020 paper on ownership of the major pharmaceuticals companies, by researchers Albert Banal-Estanol, Melissa Newham and Jo Seldeslachts, found the following (reported on the website of TRT World, a Turkish news media outlet):

“Public companies are increasingly owned by a handful of large institutional investors, so we expected to see many ownership links between companies — what was more surprising was the magnitude of common ownership… We frequently find that more than 50 per cent of a company is owned by ‘common’ shareholders who also own stakes in rival pharma companies.”

The three largest shareholders of Pfizer, J&J and Merck are Vanguard, SSGA and BlackRock.

In 2019, the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations reported that pay outs to shareholders had increased by almost 400 per cent — from $30 billion in 2000 to $146 billion in 2018. Shareholders made $1.54 trillion in profits over that 18-year period.

So, for institutional investors, the link between poor food and bad health is good for profit. While investing in the food system rakes in enormous returns, you can perhaps double your gains if you invest in pharma too.

These findings predate the 2021 documentary Monopoly: An Overview of the Great Reset, which also shows that the stock of the world’s largest corporations are owned by the same institutional investors. ‘Competing’ brands, like Coke and Pepsi, are not really competitors, since their stock is owned by the same investment companies, investment funds, insurance companies and banks.

Smaller investors are owned by larger investors. Those are owned by even bigger investors. The visible top of this pyramid shows only Vanguard and Black Rock.

A 2017 Bloomberg report states that both these companies in the year 2028 together will have investments amounting to $20 trillion.

While individual corporations — like Pfizer and Monsanto/Bayer, for instance — should be (and at times have been) held to account for some of their many wrongdoings, their actions are symptomatic of a system that increasingly leads back to the boardrooms of the likes of BlackRock and Vanguard.

Professor Fabio Vighi of Cardiff University says:

“Today, capitalist power can be summed up with the names of the three biggest investment funds in the world: BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Global Advisor. These giants, sitting at the centre of a huge galaxy of financial entities, manage a mass of value close to half the global GDP, and are major shareholders in around 90 per cent of listed companies.”

These firms help shape and fuel the dynamics of the economic system and the globalised food regime, ably assisted by the World Bank, the IMF, the WTO and other supranational institutions. A system that leverages debt, uses coercion and employs militarism to secure continued expansion.

Chapter V:

Rachel Carson and Monsanto: The Silence of Spring

Former Monsanto Chairman and CEO Hugh Grant was in the news a couple of years back. He was trying to avoid appearing in court to be questioned by lawyers on behalf of a cancer patient in the case of Allan Shelton v Monsanto.

Shelton has non-Hodgkin lymphoma and is one of the 100,000+ people in the US claiming in lawsuits that exposure to Monsanto’s Roundup weed killer and its other brands containing the chemical glyphosate caused their cancer.

According to investigative journalist Carey Gillam, Shelton’s lawyers argued that Grant was an active participant and decision maker in the company’s Roundup business and should be made to testify at the trial.

But Grant said in the court filings that the effort to put him on the stand in front of a jury is “wholly unnecessary and serves only to harass and burden” him.

His lawyers stated that Grant does not have “any expertise in the studies and tests that have been done related to Roundup generally, including those related to Roundup safety.”

Gillam notes that the court filings state that Grant’s testimony “would be of little value” because he is not a toxicologist, an epidemiologist, or a regulatory expert and “did not work in the areas of toxicology or epidemiology while employed by Monsanto.”

Bayer acquired Monsanto in 2018 and Grant received an estimated $77 million post-sale payoff. Bloomberg reported in 2017 that Monsanto had increased Grant’s salary to $19.5 million.

By 2009, Roundup-related products, which include GM seeds developed to withstand glyphosate-based applications, represented about half of Monsanto’s gross margin.

Roundup was integral to Monsanto’s business model and Grant’s enormous income and final payoff.

Consider the following quote from a piece that appeared on the Bloomberg website in 2014:

“Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Hugh Grant is focused on selling more GM seeds in Latin America to drive earnings growth outside the core US market. Sales of soybean seeds and genetic licenses climbed 16 per cent, and revenue in the unit that makes glyphosate weed killer, sold as Roundup, rose 24 per cent.”

In the same piece, Chris Shaw, a New York-based analyst at Monness Crespi Hardt & Co, is reported as saying “Glyphosate really crushed it” — meaning the sales of glyphosate were a major boost.

All fine for Grant and Monsanto. But this has had devastating effects on human health. ‘The Human Cost of Agrotoxins. How Glyphosate is killing Argentina’, which appeared on the Lifegate website in November 2015, serves as a damning indictment of the drive for earnings growth by Monsanto. Moreover, in the same year, some 30,000 doctors in that country demanded a ban on glyphosate.

The bottom line for Grant was sales and profit maximisation and the unflinching defence of glyphosate, no matter how carcinogenic to humans it is and, more to the point, how much Monsanto knew it was.

Noam Chomsky underlines the commercial imperative:

” … the CEO of a corporation has actually a legal obligation to maximize profit and market share. Beyond that legal obligation, if the CEO doesn’t do it, and, let’s say, decides to do something that will, say, benefit the population and not increase profit, he or she is not going to be CEO much longer — they’ll be replaced by somebody who does do it.”

But the cancer lawsuits in the US are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the damage done by glyphosate-based products and many other biocides.

Silent Killer

June 2022 marked 60 years since the publication of Rachel Carson’s iconic book Silent Spring. It was published just two years before her death at age 56.

Carson documented the adverse impacts on the environment of the indiscriminate use of pesticides, which she said were ‘biocides’, killing much more than the pests that were targeted. Silent Spring also described some of the deleterious effects of these chemicals on human health.

She accused the agrochemical industry of spreading disinformation and public officials of accepting the industry’s marketing claims without question. An accusation that is still very much relevant today.

Silent Spring was a landmark book, inspiring many scientists and campaigners over the years to carry on the work of Carson, flagging up the effects of agrochemicals and the role of the industry in distorting the narrative surrounding its proprietary chemicals and its influence on policy making.

In 2012, the American Chemical Society designated Silent Spring a National Historic Chemical Landmark because of its importance for the modern environmental movement.

For her efforts, Carson had to endure vicious, baseless smears and attacks on her personal life, integrity, scientific credentials and political affiliations. Tactics that the agrochemicals sector and its supporters have used ever since to try to shut down prominent scientists and campaigners who challenge industry claims, practices and products.

Although Carson was not calling for a ban on all pesticides, at the time Monsanto hit back by publishing 5,000 copies of ‘The Desolate Year’, which projected a world of famine and disease if pesticides were to be banned.

A message the sector continues to churn out even as evidence stacks up against the deleterious impacts of its practices and products and the increasing body of research which indicates the world could feed itself by shifting to agroecological/organic practices.

The title of Carson’s book was a metaphor, warning of a bleak future for the natural environment. So, all these years later, what has become of humanity’s ‘silent spring’?

In 2017, research conducted in Germany showed the abundance of flying insects had plunged by three-quarters over the past 25 years. The research data was gathered in nature reserves across Germany and has implications for all landscapes dominated by agriculture as it seems likely that the widespread use of pesticides is an important factor.

Professor Dave Goulson of Sussex University in the UK was part of the team behind the study and said that vast tracts of land are becoming inhospitable to most forms of life: if we lose the insects then everything is going to collapse.

Flying insects are vital because they pollinate flowers and many, not least bees, are important for pollinating key food crops. Most fruit crops are insect-pollinated, and insects also provide food for lots of animals, including birds, bats, some mammals, fish, reptiles and amphibians.

Flies, beetles and wasps are also predators and important decomposers, breaking down dead plants and animals. And insects form the base of thousands of food chains; their disappearance is a principal reason Britain’s farmland birds have more than halved in number since 1970.

Is this one aspect of the silence Carson warned of — that joyous season of renewal and awakening void of birdsong (and much else)? Truly a silent spring.

The 2016 State of Nature Report found that one in 10 UK wildlife species is threatened with extinction, with numbers of certain creatures having plummeted by two thirds since 1970. The study showed the abundance of flying insects had plunged by three-quarters over a 25-year period.

Campaigner Dr Rosemary Mason has written to public officials on numerous occasions noting that agrochemicals, especially Monsanto’s glyphosate-based Roundup, have devastated the natural environment and have also led to spiralling rates of illness and disease.

She indicates how the widespread use on agricultural crops of neonicotinoid insecticides and the herbicide glyphosate, both of which cause immune suppression, make species vulnerable to emerging infectious pathogens, driving large-scale wildlife extinctions, including essential pollinators.

Providing evidence to show how human disease patterns correlate remarkably well with the rate of glyphosate usage on corn, soy and wheat crops, which has increased due to ‘Roundup Ready’ seeds, Mason argues that over-reliance on chemicals in agriculture is causing irreparable harm to all beings on the planet.

In 2015, writer Carol Van Strum said the US Environmental Protection Agency has been routinely lying about the safety of pesticides since it took over pesticide registrations in 1970.

She has described how faked data and fraudulent tests led to many highly toxic agrochemicals reaching the market and they still remain in use, regardless of the devastating impacts on wildlife and human health.

The research from Germany mentioned above followed a warning by a chief scientific adviser to the UK government, Professor Ian Boyd, who claimed that regulators around the world have falsely assumed that it is safe to use pesticides at industrial scales across landscapes and the “effects of dosing whole landscapes with chemicals have been largely ignored.”

Prior to that particular warning, there was a report delivered to the UN Human Rights Council saying that pesticides have catastrophic impacts on the environment, human health and society as a whole.

Authored by Hilal Elver, the then special rapporteur on the right to food, and Baskut Tuncak, who was at the time special rapporteur on toxics, the report states: