All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

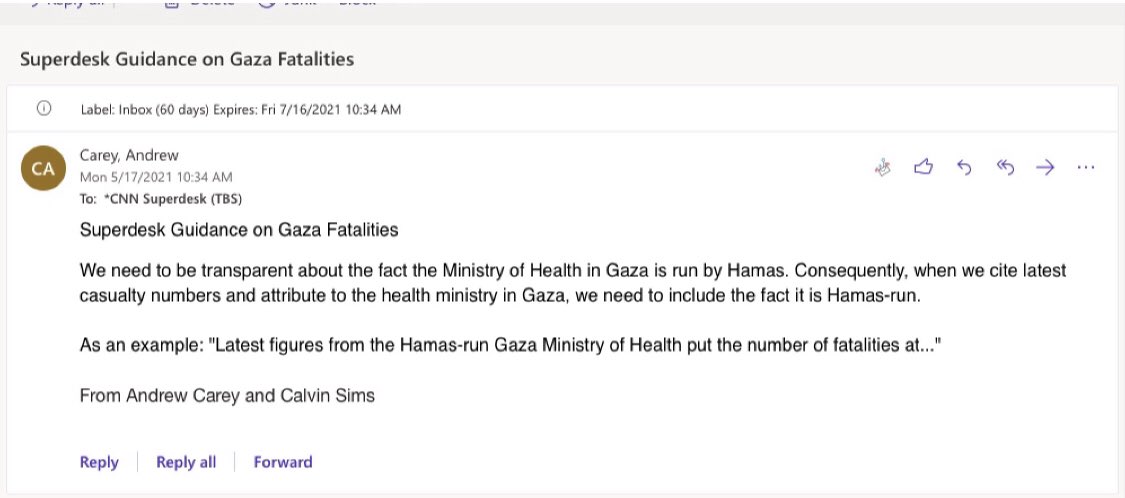

Provocative new book documents the unsavory alliance between the Mafia, the CIA, and the corporate establishment that transformed America into “the world’s most dangerous nation”

During the years of the Trump presidency, popular and scholarly discussions of the erosion of U.S. political and legal norms frequently contrasted the Trump era with a supposed golden age of U.S. democracy in the mid-20th century.

Jonathan Marshall’s new book, Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021) effectively challenges this narrative and the myth of the “greatest generation.”

The book details the largely neglected story of how well-protected criminals organized the corruption of U.S. politics and business at a national level after World War II.

Traditional U.S. historians, according to Marshall, have treated corruption as a “barely detectable eddy in the large current of events, with no lasting political or even moral significance.”

They ignore the ties between organized crime and dominant political figures, ranging from Harry S. Truman to Lyndon B. Johnson to Richard M. Nixon, along with the role of the mafia and CIA in subverting Third World nations.

As such, they present an incomplete picture, which plays into belief in “American exceptionalism”—that the country’s politics are more morally pure than other countries.

“Americans,” Marshall writes, “must arm themselves with greater knowledge of the long-neglected ‘dark quadrant’ of our national politics in order to shrink its power and strengthen our democracy.”

Harry Truman: The Pendergast’s Man

Marshall begins his story with Harry S. Truman, a failed businessman and law school student whose political rise was fueled by his backing by the mafia-linked Pendergast political machine in Kansas City.

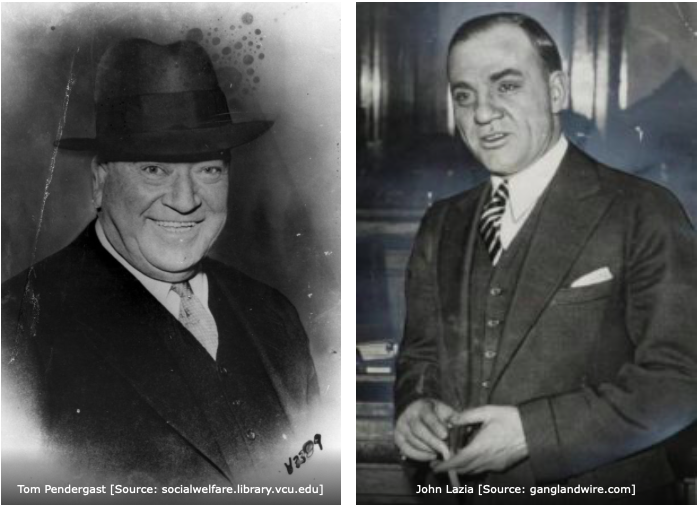

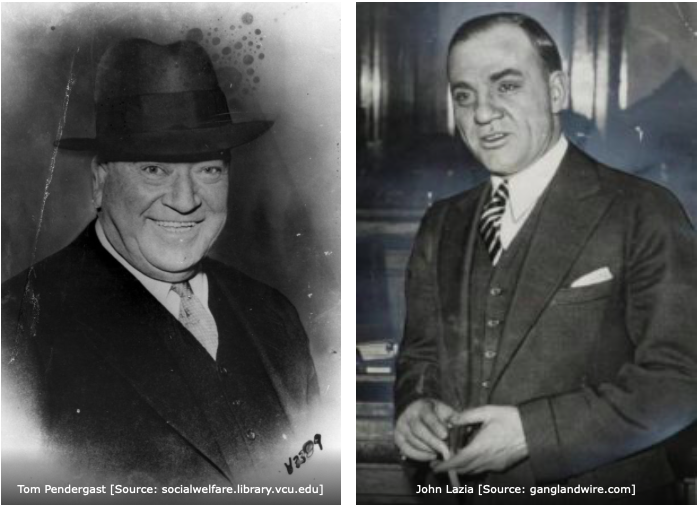

Kansas City in the 1920s was a center for vice. Thomas J. Pendergast—who was convicted in 1939 on federal tax evasion charges—was the “ruling spirit behind” the “roaring business” of gambling, prostitution, bootlegging, the sale of narcotics and racketeering,” in partnership with political boss John Lazia, an ally of Al Capone’s Chicago outfit.

Truman’s political career began in 1922 when he was elected county court judge in Eastern Missouri as Pendergast’s hand-picked candidate.

Young Truman recorded in his diary how he let a former saloon keeper and murderer who was “a friend of the big boss,” as he termed Pendergast, steal about $10,000 from the general revenues of the county, though he rationalized the decision by claiming that it “kept the crooks from getting a million or more from public bond issues.”

Political advertisement for Truman when he was running for county judge in Eastern Missouri with the backing of the Pendergast political machine. [Source: pendergastkc.org]

With Pendergast’s help, Truman won election to the Senate in 1934, just before the indictment of senior police officials in Kansas City for perjury after they had protected criminal mobs and racketeers. Within a few years, Truman was doing everything in his power to block a threatened federal investigation of rampant vote fraud in Kansas City during the 1936 election.

Truman, far left, with Pendergast to his left, at the Democratic Party national convention in Philadelphia in 1936. [Source: flatlandkc.org]

In return for this and other political favors, Pendergast allies, such as Democratic National Committee (DNC) chairman Robert Hannegan, secured Truman’s nomination as Roosevelt’s running mate at the 1944 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago over Henry Wallace, an anti-fascist progressive who had the overwhelming support of the delegates.

When Roosevelt died nine months later and Truman became president, he issued pardons to 15 members of the Pendergast machine who had been convicted of vote fraud in the 1936 election. Three weeks into his term, Truman further fired the U.S. attorney in Missouri who had prosecuted vote fraud in Kansas City and sent Pendergast to prison along with 250 members of his organization.

According to Marshall, these were the first of many acts of “favoritism, influence peddling, and outright corruption that plagued the Truman administration until voters repudiated the Democratic Party in the 1952 election.”

In a major roundup of Truman’s record published in 1951, two veteran national political reporters at Look magazine condemned the “friendships, favoritism and frauds” that had fostered “immorality” and “corruption” under Truman’s auspices. “Political morality in Washington had sunk to the lowest depths in a quarter of a century,” they charged, citing “four members of the White House staff” and “fourteen high Federal officials” among the nearly “900 Federal employees” who had been “caught trying to improve their private fortunes through their positions on the public payroll.”

This assessment contradicts the attempt by noted historians like David McCullough and Alonzo Hamby to elevate Truman’s reputation and present him as one of the nation’s great presidents.

Look magazine reported that the Truman administration’s alcohol tax unit granted scores of liquor licenses to known hoodlums and mobsters. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) under Truman further privileged issuing loans to political donors who included mob-connected business owners.

When Truman’s Attorney General, Tom Clark, protected Pendergast’s successor, the racketeer and famed bootlegger Charles Binaggio, by restricting an FBI investigation into the blatant theft of ballots during the 1946 Democratic congressional primary on behalf of Truman’s favored candidate, Truman wrote to his wife Bess that “everybody was elated.”

Binaggio went on to help Truman raise $150,000 during his hard-fought 1948 presidential campaign.

Clark meanwhile was appointed by Truman to the Supreme Court—despite calls for his impeachment as Attorney General for ordering the parole of half a dozen leaders of the Chicago crime syndicate barely a third of their way into ten-year sentences for extorting over a million dollars from Hollywood studios as a favor for Chicago’s Democratic machine.

Politics of Anti-Communism

During the 1940s and 1950s, corrupt politicians championed the politics of anti-communism in order to divert attention from the growing nexus between organized crime, big business and government.

At the center of this nexus stood FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (1924-1972), who cultivated mob connected businessmen in his war against communism, while refusing to cooperate with the Kefauver Committee’s landmark investigation of organized crime in 1950-1951.

Before being known as an anti-communist red hunter, Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-MN) had earned the moniker the “Pepsi-Cola kid” after pushing through a bill lifting federal controls for sugar that benefited Pepsi.

McCarthy also received donations and stock tips from East Texas oil billionaire Clint Murchison, Sr., prompting him to vote with the oil interests on every piece of legislation of that era, including the 27.5% oil depletion allowance, the Tidelands oil bill, which provided for state rather than federal control of submerged oil lands, and the Kerr-Thomas gas bill, which exempted the sale of natural gas from Federal Power Commission rate regulations.

In 1954, McCarthy was censured by the Senate not only because of his infamous communist smear campaign, but also because he had attempted to obstruct an investigation into his finances, which would have revealed improper payoffs by Lustron, an Ohio manufacturer of prefabricated steel houses, in return for its receipt of a generous RFC loan.

China and Dominican Lobbies

Besides McCarthy, one of the leading sponsors of anticommunist legislation in the 1950s was Pat McCarran (D-Nev.), who was known as the “gamblers Senator” and became the model for the corrupt Nevada Senator Pat Geary in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, The Godfather: Part II.

McCarran was a devoted member of the China lobby, introducing a bill to provide $1.5 billion in loans to the faltering government of Chiang Kai-Shek in China.

The U.S. government supported Chiang in the Chinese Civil War against the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Zedong. By the late 1940s, however, Chiang was hopelessly corrupt and had lost the mandate to rule in China, which had fallen to the communists.

Harry Truman meets with Madame Chiang Kai-Shek in 1945. [Source: torontopubliclibrary.ca]

Chiang and his top supporters established an effective lobby in the United States, funded in part through proceeds from the drug trade and other illicit commercial activities, which controlled the media and paid off influential politicians extending to the ranks of Defense Secretary Louis Johnson.

The China lobby’s intimidation tactics decimated the ranks of independent Asia experts to the extent that, by the mid-1950s, no one who knew anything about that part of the world remained in the State Department’s Far Eastern Division. The disastrous wars in Korea and Vietnam were a major result, along with U.S. backing of regressive governments and opium warlords in Southeast Asia.

The China lobby set the standard for other influential lobbies, such as the Dominican lobby promoting dictator Rafael Trujillo (1930-1961), who made tactical alliances with U.S. mobsters, politicians, and U.S. intelligence officials.

Like Chiang, Trujillo was effective at using the politics of anti-communism and bribed U.S. congressmen with cash and prostitutes to secure their support for a large sugar quota and arms sales.

The highest-ranking recipient of Trujillo’s cash was Vice President Richard Nixon, who allegedly pocketed $25,000 from him in September 1956 for his reelection campaign.

CIA-Mafia Alliance

Trujillo’s network helped to direct counter-revolutionary operations against Cuba following the Castroist revolution in alliance with the CIA and mobsters like Meyer Lansky who had been kicked out of Havana by Castro.

Tourists and Cubans gamble at the casino in the Hotel Nacional in Havana, 1957. Meyer Lansky who led the U.S. mob’s exploitation of Cuba in the 1950s, set up a famous meeting of crime bosses at the hotel in 1946. [Source: smithsonianmag.com]

The CIA at this time hired mob bosses Sam Giancana and Santos Trafficante Jr., to kill Castro.

The agency’s mob liaison, Johnny Rosselli, had served hard time for labor racketeering and extortion of the movie industry and was later stuffed into a 55-gallon drum and dumped into the waters off Florida after he testified before Congress about the JFK assassination.

JFK and his brother Robert had signed their death warrants when they had decided to go after the mob. They were both probably assassinated by professional criminals that had infiltrated the U.S. government and were able to operate with impunity above the law.

Mob-Connected Fixers

The corruption of the Washington political elite was enabled by the work of mob-connected fixers whose names Marshall helps resuscitate. One Henry Grunewald, who donated $1,600 to Truman’s 1948 election campaign, installed a telephone trunk line directly from his home to the Bureau of Internal Revenue so he could fix tax cases more efficiently.

Henry Grunewald. His mob connections originated with his work as a corrupt prohibition agent. [Source: vintageimagephotos]

Another, I. Irving Davidson, was described as “the representative of all that Jack and Bobby [Kennedy] fought against—Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, Hoffa’s Teamsters, the Somozas’ Nicaragua, the Texas rich, the CIA, Castro, Nixon, the mob.”

Lyndon Johnson’s closest political aide, Bobby Baker, reported a personal net worth of more than $2 million in 1963 despite receiving a salary of less than $20,000 per year, and was sued for influencing a defense contractor to hire a vending machine company, Serv-U, in which Baker had a hidden interest.

According to columnist Drew Pearson, Baker served as “the pimp” for Johnson along with President Kennedy and Senator George Smathers. He would introduce them and other congressmen to beautiful women at the plush Carousel resort motel he owned in Maryland and Quorum club he helped establish across from the Senate office building, where they could relax with “party girls.”

One of Johnson’s first calls after returning to Washington following the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, was to get an update from Abe Fortas, his crisis adviser and Baker’s attorney, on burgeoning congressional investigations into Baker’s influence peddling, sweetheart business deals and Washington sex—something that Johnson was very apprehensive about.

Part of Baker’s fortune was made in consort with some of the Kennedy Justice Department’s top targets for prosecution. Among them was Edward Levinson, a senior associate of Meyer Lansky, who headed casino operations at the Havana Riviera before the Cuban revolution, and then invested with Lansky and Frank Sinatra in the Sands hotel in Las Vegas.

An FBI bug overheard Levinson arranging with Baker to fix the award of a federal architectural contract on behalf of a Las Vegas firm in return for its owners purchasing eight $1,000 tickets to a Democratic fundraising dinner hosted by President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson in January 1963.[1]

According to Jack Halfen, a partner of New Orleans mob boss Carlos Marcello, Johnson accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars from syndicate-backed businesses over the span of a decade, and in return helped kill anti-racketeering legislation in the Senate, including that which banned interstate transportation of slot machines, regulated racing wires, [and] aimed to rewrite the tax laws to make it tougher on gamblers.

A Maryland insurance broker, Don Reynolds, testified before the Senate that Johnson also had demanded illegal kickbacks in exchange for political gifts.

Murchisons

One of Johnson’s primary financiers dating back to the beginning of his political career in the early 1940s was Clint Murchison Sr. (1895-1969), an East Texas oil millionaire and Baker associate who had connections to the Genovese crime family, the Chicago Al Capone outfit, Las Vegas gamblers and the Teamsters.

For years, Johnson would attend breakfasts at Murchison’s home to collect campaign cash and returned the favor by ensuring generous subsidies to the oil and gas industry.

After World War II, Johnson campaigned to overturn the regulation of natural gas prices by the Federal Power Commission and launched a red-baiting campaign against a progressive member of the commission, Leland Olds.

The latter’s removal exemplified the emergence of a bullying political culture in Washington in which advocates of the public interest were branded as traitors.

The TFX Scandal

In November 1962, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Navy Secretary Fred Korth and Air Force Secretary Eugene Zuckert overruled four previous Pentagon evaluation panels and awarded General Dynamics and its main partner, Northrop Grumman, a $7 billion contract for the Tactical Fighter (Experimental) TFX, which became known as the F-111.

A month before the announcement, the Fort Worth Press published a story citing top government sources, which warned of a political fix.

It noted that General Dynamics’ largest shareholder, Henry Crown, would have been well-positioned to nudge the selection process in his favor as President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson owed their 1960 victory in part to the Democratic machines of Jacob Arvey in Illinois and Arvey’s protégé Paul Ziffren in California, along with their hidden patrons in the Chicago outfit, all of whom were tight with Crown.

On November 20th, a member of the Senate investigations subcommittee strongly hinted that Vice President Johnson might have wielded his influence to steer the TFX award to his home state contractor (General Dynamics, based in Fort Worth). Inside the Pentagon, the TFX was known as the LBJ.

On November 22nd, the day of Kennedy’s assassination, Drew Pearson had prepared an explosive column alleging that Johnson had intervened with Air Force Secretary Zuckert to swing the contract to General Dynamics. It also implicated Henry Crown—who had put $1,000 into LBJ’s campaign for the Democratic Party nomination in 1960—and raised questions about links to Bobby Baker and his infamous Quorum Club.

When Kennedy was killed, it conveniently blotted the TFX scandal out of the nation’s consciousness. Pearson was forced to cancel his column and TFX hearings planned by anti-corruption crusader John McClellan’s subcommittee were called off, resuming only in 1969 after Johnson had left the Oval Office.

In secret testimony before the Rules Committee on December 1, 1964, Don Reynolds testified that, one day when he was in Bobby Baker’s office, Baker showed him $100,000 worth of hundred dollar bills that Roy Evans, the President of Grumman Aircraft, had left in a paper bag “for the TFX contract.”

Reynolds also stated that “the leader” (Johnson) “had interceded to make sure that the TFX was awarded to General Dynamics Corporation.”

The committee referred the matter to the FBI for investigation, though with little apparent follow-through.

Here’s to the State of Richard Nixon

Besides Johnson, Henry Crown had contributed generously to Richard Nixon, prompting Nixon to visit Fort Worth in the final days of the 1968 presidential campaign where he declared that the F-111 would be “made into one of the foundations of our air supremacy.”

In January 1972, President Nixon approved a controversial $5.5 billion space shuttle development program with General Dynamics as a prime subcontractor to North American Rockwell (successor to North American Aviation), while Henry Crown handed over a $25,000 contribution to the Committee to Re-Elect the President.

Nixon’s relationship with Crown fit a pattern that dated back to his first race for Congress in 1946 against liberal incumbent Jerry Voorhis.

The young Nixon at that time amassed tens of thousands of dollars in unreported contributions from southern California oil companies, banks and movie moguls, whose favor he returned by supporting legislation to curb unions, exempt key industries from anti-trust action, promote oil drilling, and cut funding for public housing and education.

[Source: nixonfoundation.org]

Nixon’s 1946 campaign was also critical because it began his career-long partnership with his ruthless political consultant, Murray Chotiner, a Beverly Hills lawyer whose clients were mostly bookmakers and gamblers. Chotiner had one word of advice for Nixon: attack. Nixon’s successful House and Senate campaigns in 1946 and 1950 were notoriously ugly, full of insinuations that his opponents were soft on communism and crime.

Chotiner introduced Nixon to Jewish mobster Mickey Cohen, who ended up in Alcatraz after being convicted of tax evasion in 1951 and again in 1961. Cohen donated $5,000 to Nixon’s 1946 congressional campaign (about $50,000 in today’s dollars) and squeezed other colleagues in the underworld for more contributions.

After Nixon came back to win the 1968 presidential election on a law-and-order platform, Cohen wrote to columnist Jack Anderson: “In my wildest dreams (never) could I ever have visualized or imagined 17 or 18 years ago that the likes of Richard Nixon could possibly become president of the United States. Let’s hope that he isn’t the same guy that I knew: a rough hustler (and) a goddamn small-time ward politician.” (p. 178)

Of course, Nixon remained always the same.

While signing into law the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 as president, most of his Justice Department’s organized crime targets were allies of big-city Democratic Party politicians.

President Nixon also fired one of the country’s most effective organized crime prosecutors, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Robert Morgenthau, who just before had directed a grand jury to investigate Cosmos Bank of Zurich, where Nixon was suspected of having a secret account.[2]

Additionally, Nixon fired U.S. Attorney in San Diego Ed Miller, one of the “city’s true battlers against entrenched corruption,” who prosecuted the brother of the business partner of one of Nixon’s closest personal associates and biggest campaign contributors, C. Arnholt Smith, the owner of the San Diego Padres, who had raised $1 million for Nixon’s 1968 election.

When an IRS investigator handed Miller’s replacement, Harry Steward, a report on illegal campaign contributions by Smith and acts of bribery that violated the Corrupt Practices Act, Steward allegedly told him to “knock it off” and refused to issue a grand jury subpoena.

Nixon’s close ties to the mob emerged from his long political alliance with the Teamsters Union, which was a prime ally of the Chicago outfit along with the Hollywood studios as they crushed a militant Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and supported the anti-communist purge of the motion picture industry.

Teamsters President Jimmy Hoffa was investigated by the Justice Department in 1957 for involvement in a fraudulent Florida venture (Sun Valley) that sold boggy land to unsuspecting Teamster members as retirement property.

He gave generously to Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign and encouraged other Teamsters to do the same in 1968 when Hoffa was behind bars after being convicted of mail and wire fraud for improper use of Teamsters pension funds.

Once in the Oval Office, Nixon got the Justice Department to indict the key federal witness against Hoffa twice, and instructed Attorney General Richard Kleindienst to derail any further investigations against Hoffa or his allies.

Nixon further helped secure Hoffa’s release from prison while plans were being developed to recruit Teamster “thugs” to beat up anti-war demonstrators.[3]

Nixon’s moral turpitude was exposed on a wide scale during the Watergate hearings, which were prompted by Nixon’s illegal spying on his Democratic Party rivals during the 1972 election.

The burglars who broke into the Watergate Hotel were globe-trotting CIA officers who had been involved in the 1954 Guatemalan coup, the Bay of Pigs and CIA-mafia plots against Castro, which Nixon championed.

[Source: twitter.com]

According to ringleader G, Gordon Liddy, the purpose of the break-in was to determine what dirty secrets the DNC’s boss, Lawrence O’Brien, had learned about Nixon while working as the Howard Hughes organization’s top Washington political adviser after the 1968 election.

These secrets included $100,000 in cash payoffs made by Hughes, owner of a major aerospace company, via Nixon’s close friend, Charles “Bebe” Rebozo, in 1969 and 1970, and Nixon’s treasonous sabotage of Lyndon B. Johnson’s proposed peace talks with North Vietnam in 1968, which would have benefitted Nixon’s adversary, Hubert Humphrey, in the election.

Triumph of the Deep State

Donald J. Trump was a direct heir of Nixon: Both were mentored by Joe McCarthy’s mob-connected lawyer, Roy Cohn, and ruthlessly attacked their opponents.

Trump’s ties to organized crime dated back to his years as a New York real estate mogul when he hired demolition workers controlled by the Genovese crime family and purchased concrete from companies owned by mafia families.

Though Trump’s supporters were convinced that Trump was a victim of a “deep state” conspiracy against him, Trump’s election was in fact a culmination of the triumph of “deep politics,” which Marshall defines as a “form of organized and systematic corruption, or covert influencing of policy and administration, on a scale that subverts national democratic norms.”

The organized and systemic corruption was briefly exposed in the 1950s Kefauver hearings on organized crime and as a result of the Watergate scandal and Church Committee investigations into the CIA, but never effectively contained.

The presidents featured in Dark Quadrant were able to pass some progressive legislation—ranging from the desegregation of the armed forces under Truman to the Civil Rights Act, Medicaid and anti-poverty initiatives under Johnson, to Nixon’s establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and presided over a period of economic prosperity.

However, they ultimately governed in the interests of their corporate and mob-linked donors, betrayed democratic values, and corroded the nation’s moral fabric.

With a new Cold War heating up, U.S. leaders now strive to present U.S. global leadership as necessary to save the world from Russian and Chinese autocracy.

Marshall’s study reminds us, however, that the United States evolved after World War II as a corrupted dollarocracy. Its rhetoric about promoting democracy around the world as such rings hollow.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of CovertAction Magazine. He is the author of four books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019) and The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018). He can be reached at: [email protected].

Notes

1. Levinson was involved in a scam to launder casino revenues for the mafia along with Benjamin Sigelbaum, another of Baker’s business associates who had invested in Serv-U.

2. Morgenthau was also an enemy of Nixon political ally Roy Cohn, who was facing a trial on federal charges of conspiracy, mail fraud, bribery, extortion and blackmail.

3. After being forced to resign from the White House in disgrace, Nixon’s first public appearance was at a Teamsters golf tournament.

Featured image: Harry S. Truman and Kansas City mafia boss Tom Pendergast in 1919. [Source: cafnr.missouri.edu]