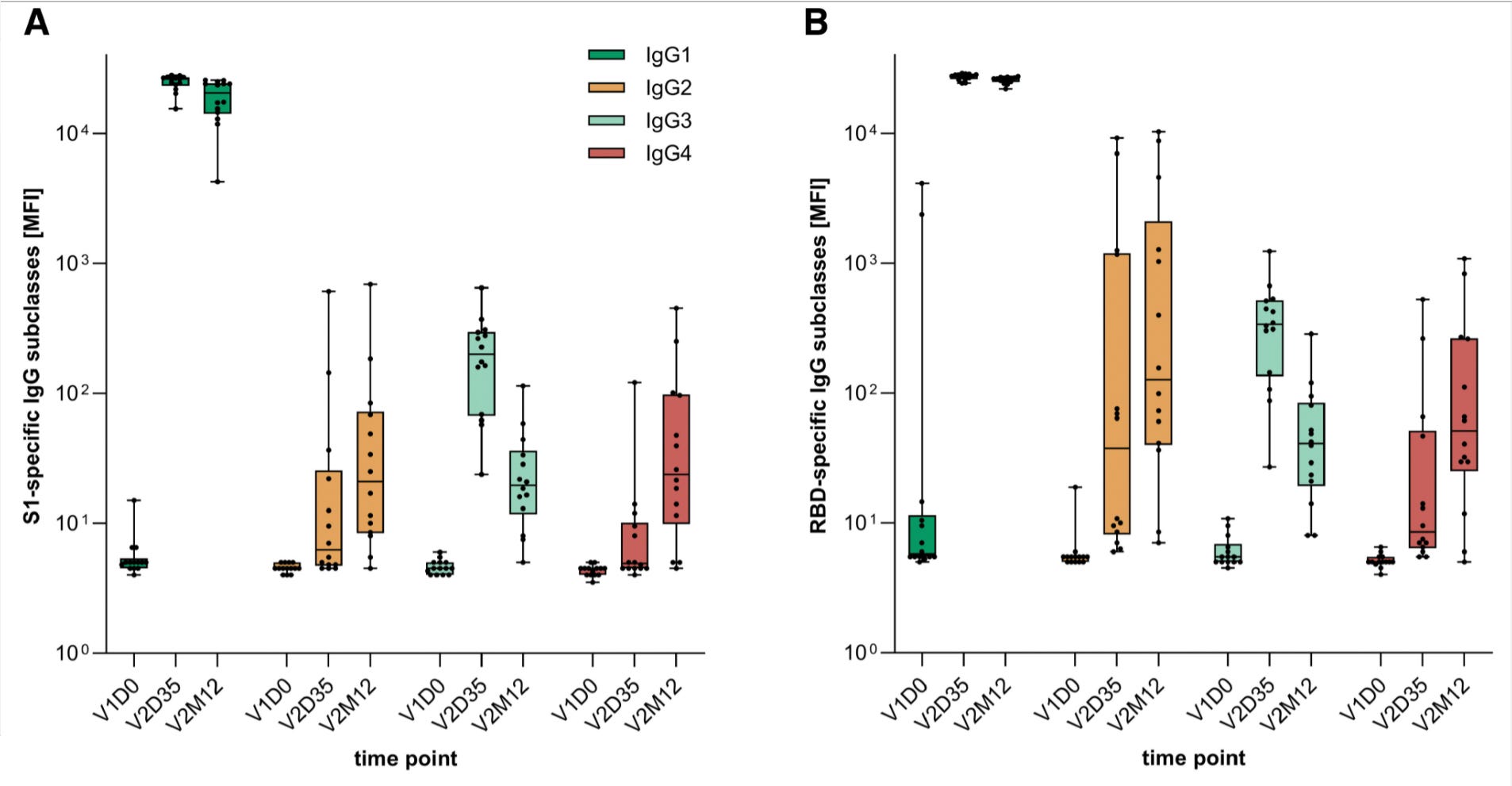

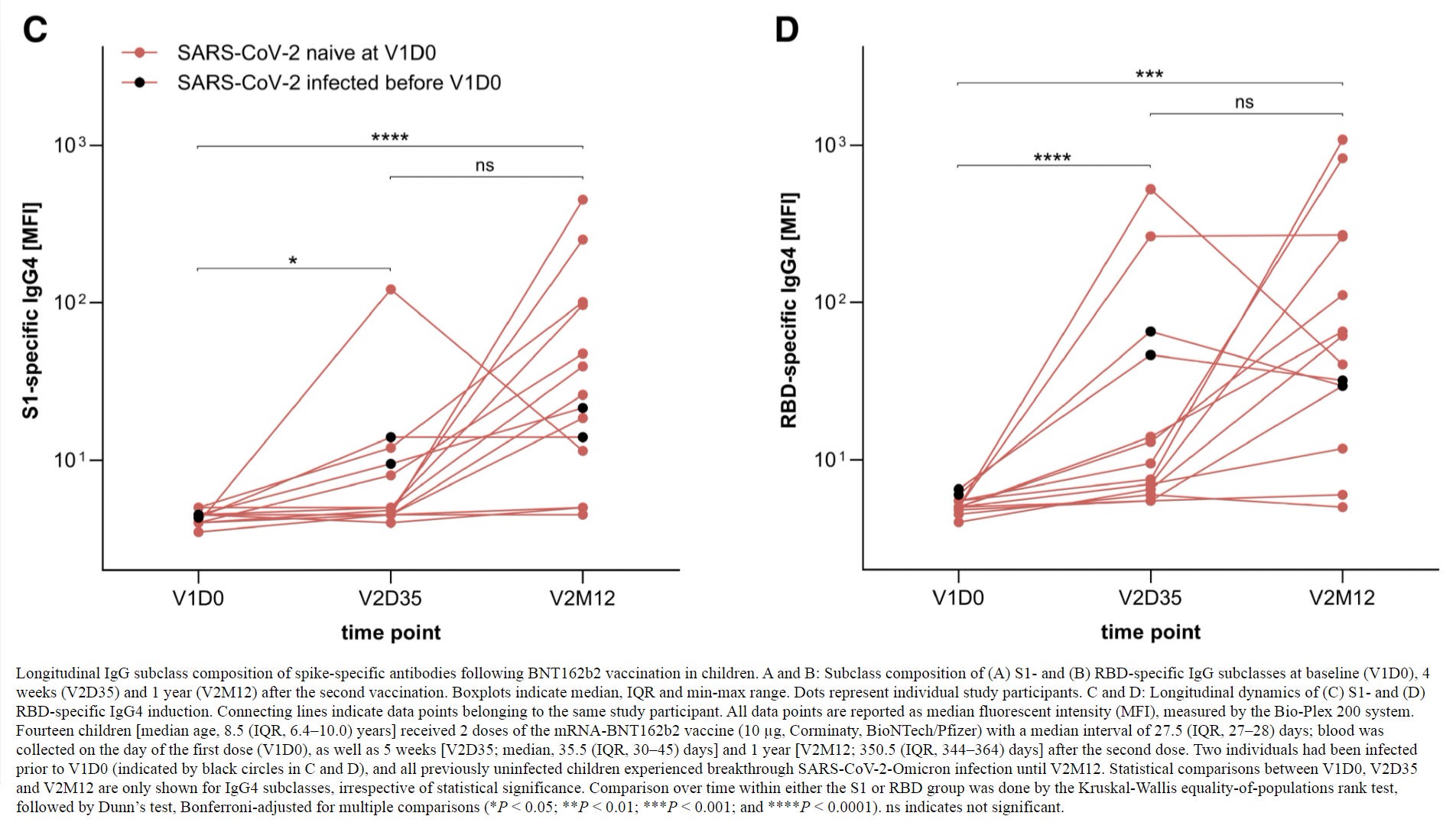

Introduction and Update

Outstanding and timely analysis: this article by Charlotte Greenfield documents the Taliban government’s current project to eradicate opium and implement crop substitution.

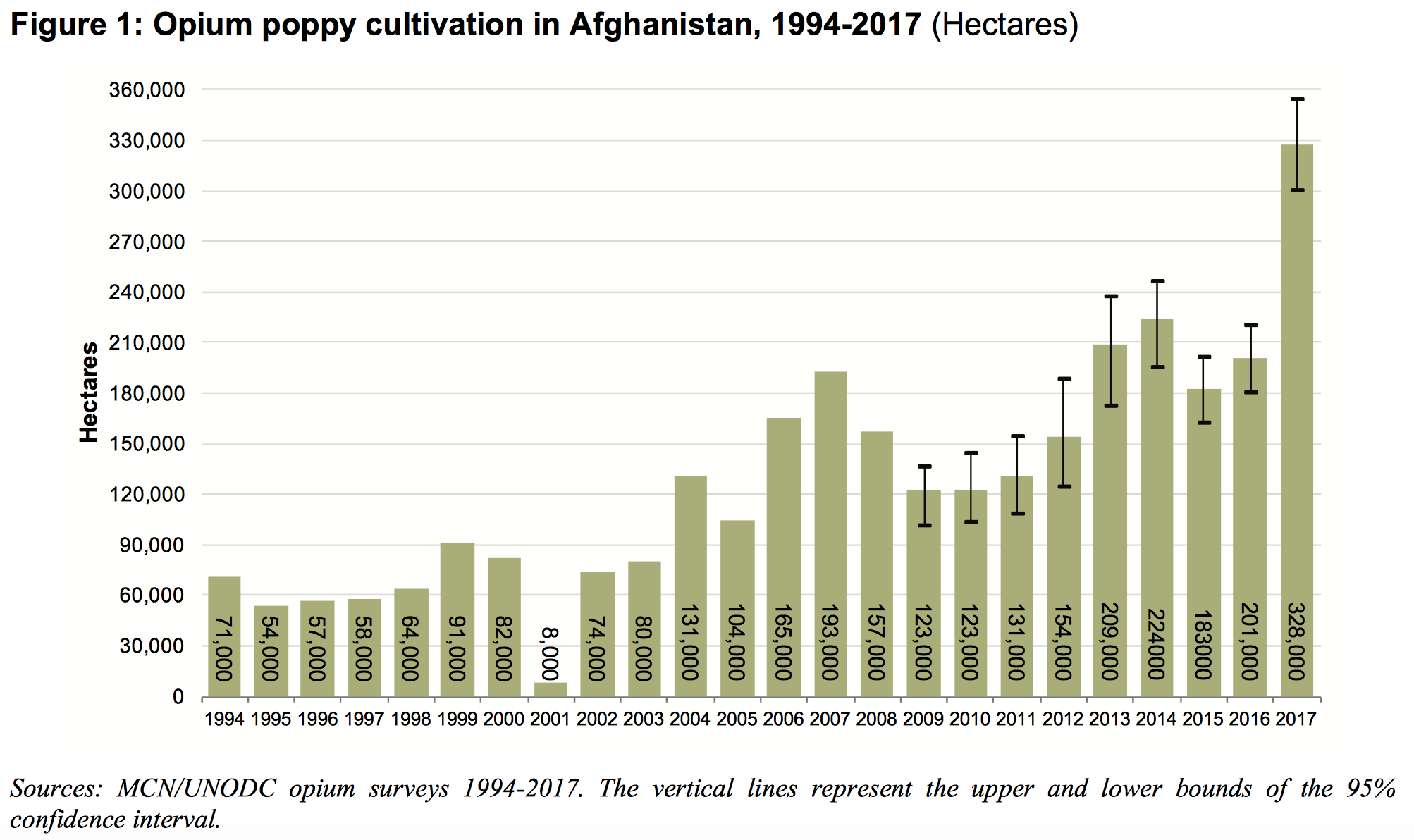

What is significant is that in the year 2000-2001, a similar project was implemented under UN auspices — presented to the UN General Assembly in October 2001– at the height of the US-NATO invasion .

The Taliban government –in collaboration with the United Nations– had imposed a successful ban on poppy cultivation.

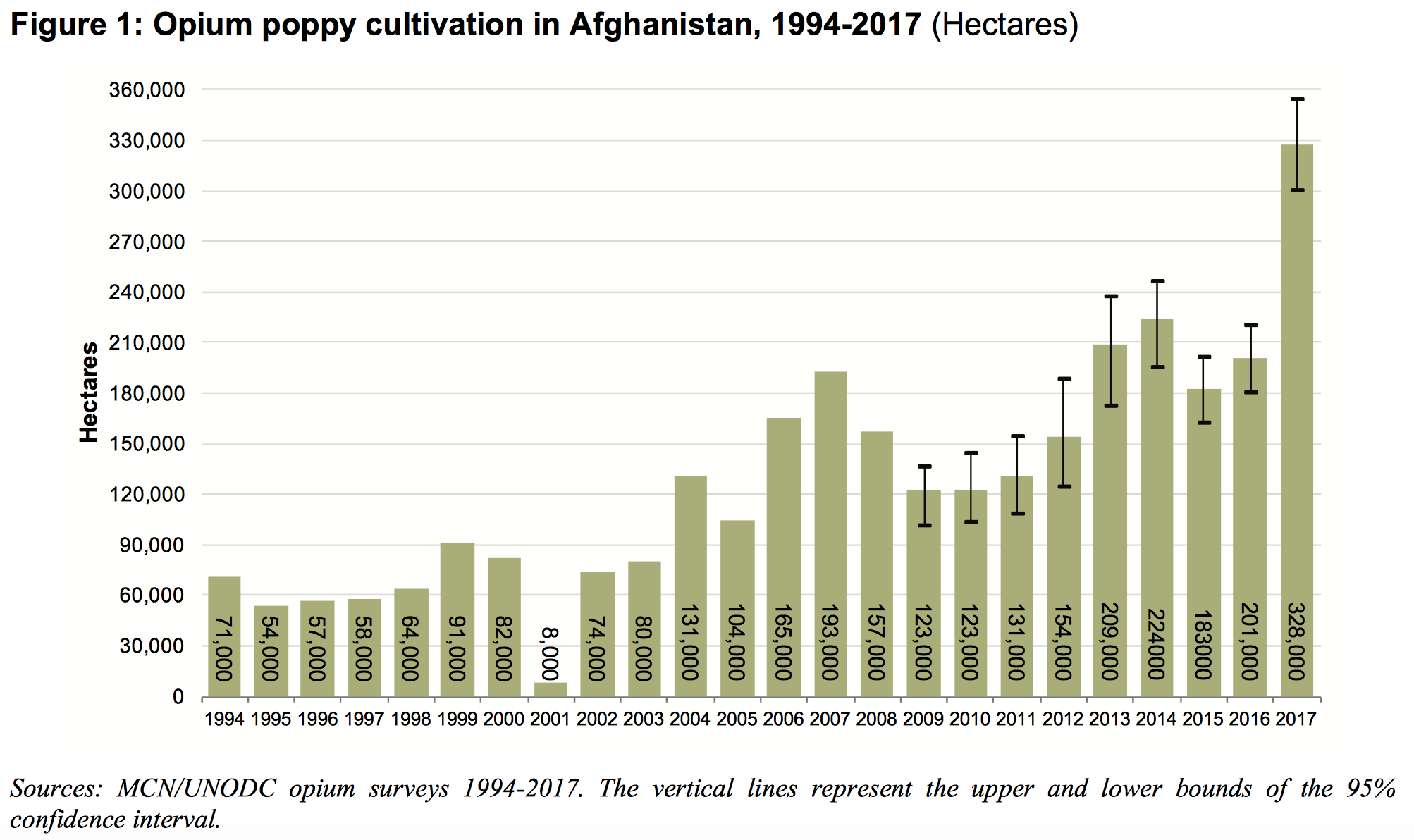

Opium production declined by more than 90 per cent in 2001.

Heroin is a multibillion dollar business supported by powerful interests, which requires a steady and secure commodity flow.

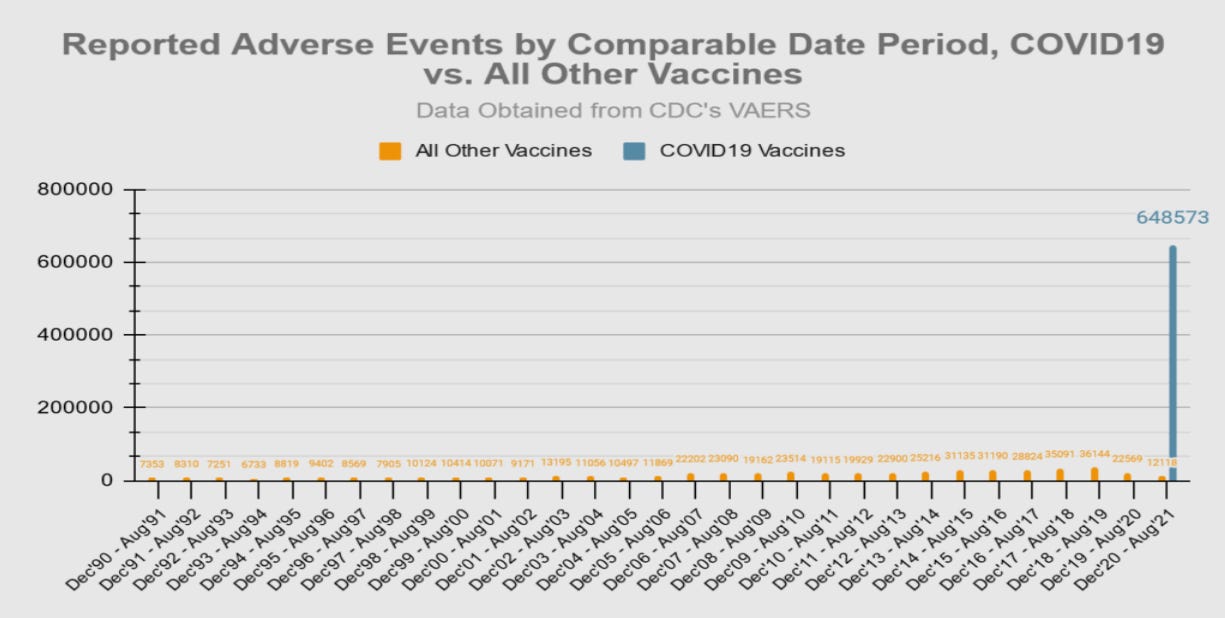

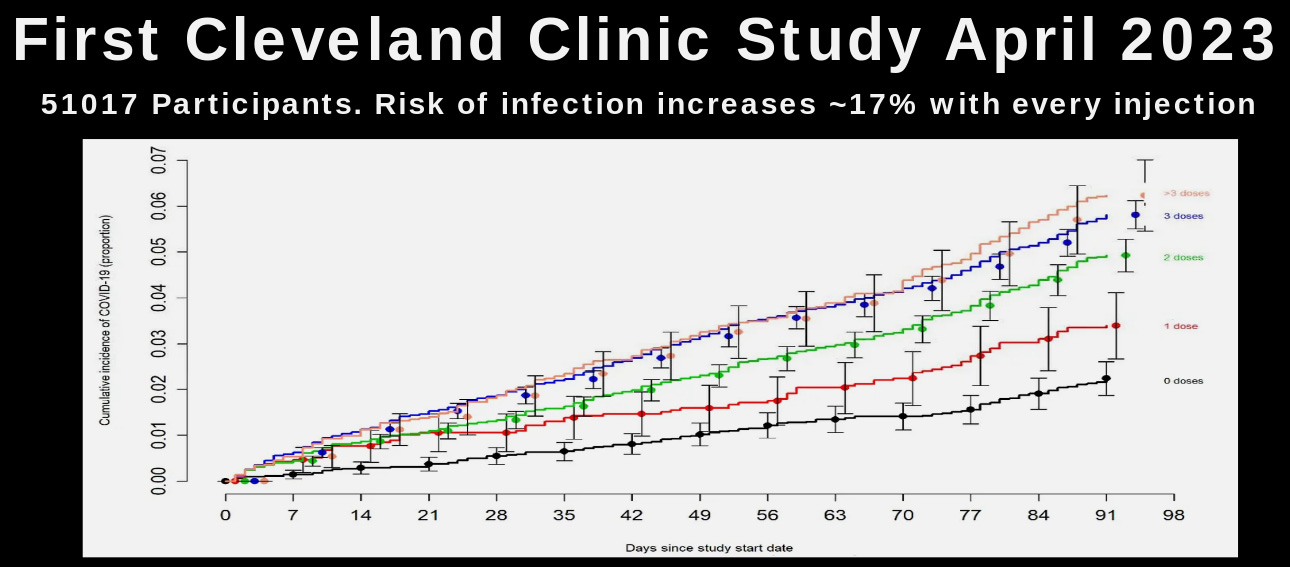

One of the “unspoken” objectives of the October 7, 2001 war against Afghanistan was to restore the U.S. sponsored drug trade to its historical levels and exert direct control over the drug routes. (see graph above)

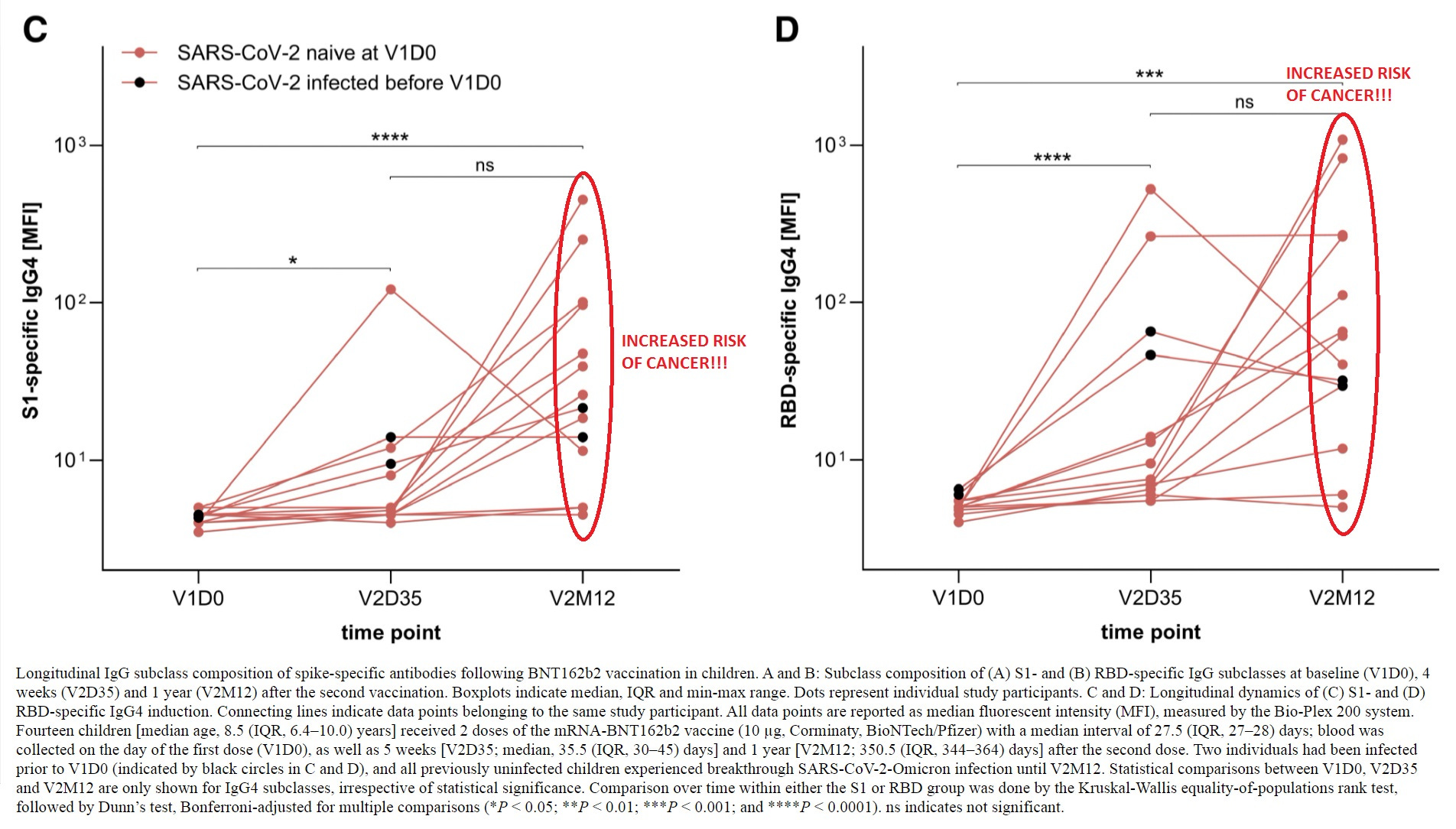

Immediately following the October 2001 invasion, opium markets were restored. Opium prices spiraled. By early 2002, the opium price (in dollars/kg) was almost 10 times higher than in 2000.

In 2001, under the Taliban opiate production stood at 185 tons, increasing to 3400 tons in 2002 under the US sponsored puppet regime of President Hamid Karzai.

In fact the surge in opium cultivation production coincided with the onslaught of the US-led military operation (October 2001) and the downfall of the Taliban regime.

From October through December 2001, farmers started to replant poppy on an extensive basis.

In recent developments, according to the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (5 November 2023):

Opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan plunged by an estimated 95 per cent following a drug ban imposed by the de facto authorities in April 2022, according to a new research brief from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

UN officials noted that the near-total contraction of the opiate economy is expected to have far-reaching consequences and highlighted the urgent need for enhanced assistance for rural communities, accompanied by alternative development support to build an opium-free future for the people of Afghanistan.

Opium cultivation fell across all parts of the country, from 233,000 hectares to just 10,800 hectares in 2023. The decrease has led to a corresponding 95 per cent drop in the supply of opium, from 6,200 tons in 2022 to just 333 tons in 2023.

The sharp reduction has had immediate humanitarian consequences for many vulnerable rural communities who relied on income from cultivating opium. Farmers’ income from selling the 2023 opium harvest to traders fell by more than 92 per cent from an estimated US$1,360 million for the 2022 harvest to US$110 million in 2023.

“This presents a real opportunity to build towards long-term results against the illicit opium market and the damage it causes both locally and globally,” said Ghada Waly, Executive Director of UNODC. “At the same time, there are important consequences and risks that need to be addressed for an outcome that is ultimately positive and sustainable, especially for the people of Afghanistan.”

The impact on the Global Trade in Heroin which is estimated to be in excess of 100 billion dollars has created havoc.

Heroin is a multibillion dollar trade. What are the broader implications? Will this second attempt by the Taliban government to restrict the drug trade lead to U.S military intervention with a view to restoring the multibillion dollar trade in heroin?

In a recent report by the Crisis Group:

The Taliban have been blamed for undermining Afghanistan’s “illegal narcotics industry” to the detriment of Afghanistan’s peasantry: “rounding up drug users, destroying opium poppy and cannabis fields, … their initiative strikes at the backbone of Afghanistan’s informal economy and the livelihoods of the rural poor.”

“Why does it matter? The ban has drastically reduced cultivation, but Afghan-produced drugs are still hitting the global market as dealers continue selling stockpiles and some farmers resist the ban. The Taliban’s crackdown has devastated the economic outlook for farmers and rural labourers with few other employment options. Women have been particularly affected.”

What is not mentioned is the impact of the multibillion opium trade controlled by powerful business interests.

America’s “humanitarian option” is to restore opium cultivation, with a view to saving the West’s multibillion dollar narcotics trade (controlled by the financial elites)

According to The Global Financial Integrity report entitled “Transnational Crime and the Developing World” the estimated retail value of the global illicit drug market is between US$426 and US$652 billion in 2014.

Other sources –which do not address the retail value estimate as well the issue of money laundering– estimate the trade in narcotics to be of the order of US$300- 400 billion, which is in excess of the Worldwide trade in LNG natural gas estimated at US$160 billion in 2019. (These estimates are subject to verification).

Michel Chossudovsky, Global Research, October 6, 2024.

***

“Empire of Drugs”: Taliban’s Eradication of Opium

Reveals Harsh Reality of U.S. Occupation of Afghanistan

Charlotte Greenfield

Free Thought Project

November 5, 2024

For the entirety of the 20 year US occupation, Afghanistan was the primary source for 90% of the world’s heroin. In just over a year the Taliban has nearly eradicated Afghani heroin production, raising serious questions about the US role in facilitating the global drug trade.

The Taliban government in Afghanistan – the nation that until recently produced 90% of the world’s heroin – has drastically reduced opium cultivation across the country. Western sources estimate an up to 99% reduction in some provinces. This raises serious questions about the seriousness of U.S. drug eradication efforts in the country over the past 20 years. And, as global heroin supplies dry up, experts tell MintPress News that they fear this could spark the growing use of fentanyl – a drug dozens of times stronger than heroin that already kills more than 100,000 Americans yearly.

The Taliban Does What the US Did Not

It has already been called “the most successful counter-narcotics effort in human history [2000-2001].” Armed with little more than sticks, teams of counter-narcotics brigades travel the country, cutting down Afghanistan’s poppy fields.

In April of last year [2022], the ruling Taliban government announced the prohibition of poppy farming, citing both their strong religious beliefs and the extremely harmful social costs that heroin and other opioids – derived from the sap of the poppy plant – have wrought across Afghanistan.

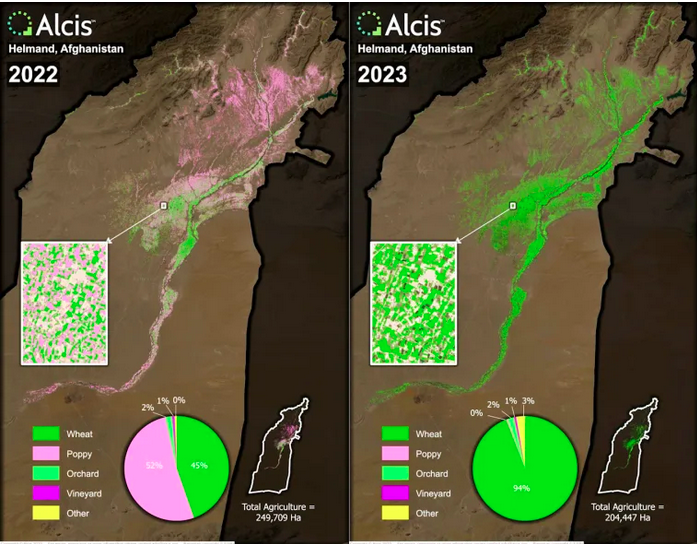

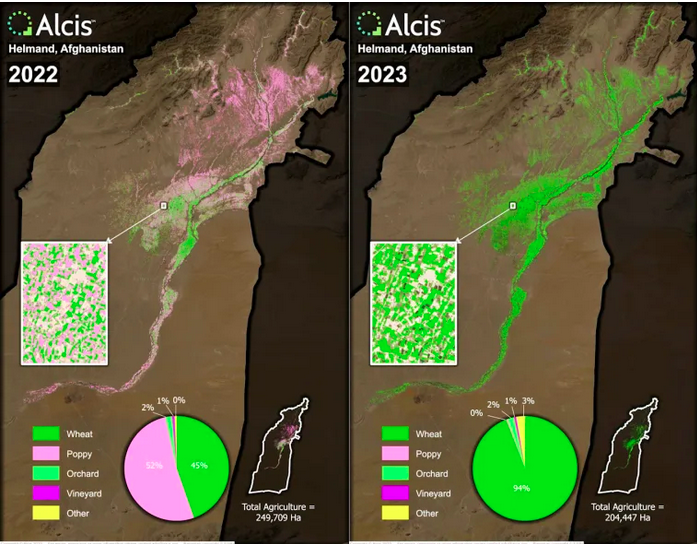

It has not been all bluster. New research from geospatial data company Alcis suggests that poppy production has already plummeted by around 80% since last year.

Indeed, satellite imagery shows that in Helmand Province, the area that produces more than half of the crop, poppy production has dropped by a staggering 99%. Just 12 months ago, poppy fields were dominant. But Alcis estimates that there are now less than 1,000 hectares of poppy growing in Helmand.

Instead, farmers are planting wheat, helping stave off the worst of a famine that U.S. sanctions helped create. Afghanistan is still in a perilous state, however, with the United Nations warning that six million people are close to starvation.

Data from Alcis shows that a majority of Afghan farmers switched from growing poppy to wheat in a single year

The Taliban waited until 2022 to impose the long-awaited ban in order not to interfere with the growing season. Doing so would have provoked unrest among the rural population by eradicating a crop that farmers had spent months growing. Between 2020 and late 2022, the price of opium in local markets rose by as much as 700%. Yet given the Taliban’s insistence – and their efficiency at eradication – few have been tempted to plant poppies.

The poppy ban has been matched by a similar campaign against the methamphetamine industry, with the government targeting the ephedra crop and shutting down ephedrine labs across the country.

A Looming Catastrophe

Afghanistan produces almost 90% of the world’s heroin. Therefore, the eradication of the opium crop will have profound worldwide consequences on drug use. Experts MintPress spoke to warned that a dearth of heroin would likely produce a huge spike in the use of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, a drug the Center for Disease Control estimates is 50 times stronger and is responsible for taking the lives of more than 100,000 Americans each year.

“It is important to consider past periods of heroin shortages and the impact these have had on the European drug market,” the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) told MintPress, adding:

Experience in the E.U. with previous periods of reduced heroin supply suggests that this can lead to changes in patterns of drug supply and use. This can include further an increase in rates of polysubstance use among heroin users. Additional risks to existing users may be posed by the substitution of heroin with more harmful synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and its derivatives and new potent benzimidazole opioids.”

In other words, if heroin is no longer available, users will switch to far deadlier synthetic forms of the drug. A 2022 United Nations report came to a similar conclusion, noting that the crackdown on heroin production could lead to the “replacement of heroin or opium by other substances…such as fentanyl and its analogs.”

“It does have that danger in the macro sense, that if you take all that heroin off the market, people are going to go to other products,” Matthew Hoh told MintPress.

Hoh is a former State Department official who resigned from his post in Zabul Province, Afghanistan, in 2009. “But the response should not be reinvade Afghanistan, reoccupy it and put the drug lords back in power, which is basically what people are implying when they bemoan the consequence of the Taliban stopping the drug trade,” Hoh added;

“Most of the people who are speaking this way and worrying out loud about it are people who want to find a reason for the U.S. to go and affect regime change in Afghanistan.”

There certainly has been plenty of hand-wringing from American sources. “Foreign Policy,” wrote about “how the Taliban’s ‘war on drugs’ could backfire;” U.S. government-funded “Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty” claimed that the Taliban were turning a “blind eye to opium production,” despite the official ban. And the United States Institute of Peace, an institution created by Congress that is “dedicated to the proposition that a world without violent conflict is possible,” stated emphatically that “the Taliban’s successful opium ban is bad for Afghans and the world”.

This looming catastrophe, however, will not hit immediately. Significant stockpiles of drugs along trafficking routes still exist. As the EMCDDA told MintPress:

It can take over 12 months before the opium harvest appears on the European retail drug market as heroin – and so it is too early to predict, at this stage, the future impact of the cultivation ban on heroin availability in Europe. Nonetheless, if the ban on opium cultivation is enforced and sustained, it could have a significant impact on heroin availability in Europe during 2024 or 2025.”

Yet there is little indication that the Taliban are anything but serious about eradicating the crop, indicating that a heroin crunch is indeed coming.

A similar attempt by the Taliban to eliminate the drug occurred in 2000, the last full year that they were in power. It was extraordinarily successful, with opium reduction dropping from 4,600 tons to just 185 tons. At that time, it took around 18 months for the consequences to be felt in the West. In the United Kingdom, average heroin purity fell from 55% to 34%, while in the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, heroin was largely replaced by fentanyl. However, as soon as the United States invaded in 2001, poppy cultivation shot back up to previous levels and the supply chain recommenced.

US Complicity in the Afghan Drug Trade

The Taliban’s successful campaign to eradicate drug production has cast a shadow of doubt over the effectiveness of American-led endeavors to achieve the same outcome. “It prompts the question, ‘What were we actually accomplishing there?!’” remarked Hoh, underscoring:

This undermines one of the fundamental premises behind the wars: the alleged association between the Taliban and the drug trade – a concept of a narco-terror nexus. However, this notion was fallacious. The reality was that Afghanistan was responsible for a staggering 80-90% of the world’s illicit opiate supply. The primary controllers of this trade were the Afghan government and military, entities we upheld in power.”

Hoh clarified that he never personally witnessed or received any reports of direct involvement by U.S. troops or officials in narcotics trafficking. Instead, he contended that there existed a “conscious and deliberate turning away from the unfolding events” during his tenure in Afghanistan.’

Suzanna Reiss, an academic at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the author of “We Sell Drugs: The Alchemy of U.S. Empire,” demonstrated an even more cynical perspective on American counter-narcotics endeavors as she conveyed to MintPress:

The U.S. has never really been focused on reducing the drug trade in Afghanistan (or elsewhere for that matter). All the lofty rhetoric aside, the U.S. has been happy to work with drug traffickers if the move would advance certain geopolitical interests (and indeed, did so, or at least turned a knowingly blind eye, when groups like the Northern Alliance relied on drugs to fund their political movement against the regime.).”

Afghanistan’s transformation into a preeminent narco-state owes a significant debt to Washington’s actions.

Poppy cultivation in the 1970s was relatively limited. However, the tide changed in 1979 with the inception of Operation Cyclone, a massive infusion of funds to Afghan Mujahideen factions aimed at exhausting the Soviet military and terminating its presence in Afghanistan.

The U.S. directed billions toward the insurgents, yet their financial needs persisted. Consequently, the Mujahideen delved into the illicit drug trade. By the culmination of Operation Cyclone, Afghanistan’s opium production had soared twentyfold. Professor Alfred McCoy, acclaimed author of “The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade,” shared with MintPress that approximately 75% of the planet’s illegal opium output was now sourced from Afghanistan, a substantial portion of the proceeds funneling to U.S.-backed rebel factions.

Unraveling the Opioid Crisis: An Impending Disaster

The opioid crisis is the worst addiction epidemic in U.S. history. Earlier this year, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas described the American fentanyl problem as “the single greatest challenge we face as a country.” Nearly 110,000 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2021, fentanyl being by far the leading cause. Between 2015 and 2021, the National Institute of Health recorded a nearly 7.5-fold increase in overdose deaths. Medical journal The Lancet predicts that 1.2 million Americans will die from opioid overdoses by 2029.

U.S. officials blame Mexican cartels for smuggling the synthetic painkiller across the southern border and China for producing the chemicals necessary to make the drug.

White Americans are more likely to misuse these types of drugs than other races. Adults aged 35-44 experience the highest rates of deaths, although deaths among younger people are surging. Rural America has been particularly hard hit; a 2017 study by the National Farmers Union and the American Farm Bureau Federation found that 74% of farmers have been directly impacted by the opioid epidemic. West Virginia and Tennessee are the states most badly hit.

For writer Chris Hedges, who hails from rural Maine, the fentanyl crisis is an example of one of the many “diseases of despair” the U.S. is suffering from. It has, according to Hedges,

“risen from a decayed world where opportunity, which confers status, self-esteem and dignity, has dried up for most Americans. They are expressions of acute desperation and morbidity.”

In essence, when the American dream fizzled out, it was replaced by an American nightmare. That white men are the prime victims of these diseases of despair is an ironic outgrowth of our unfair system. As Hedges explained:

White men, more easily seduced by the myth of the American dream than people of color who understand how the capitalist system is rigged against them, often suffer feelings of failure and betrayal, in many cases when they are in their middle years. They expect, because of notions of white supremacy and capitalist platitudes about hard work leading to advancement, to be ascendant. They believe in success.”

In this sense, it is important to place the opioid addiction crisis in a wider context of American decline, where opportunities for success and happiness are fewer and farther between than ever, rather than attribute it to individuals. As the “Lancet” wrote: “Punitive and stigmatizing approaches must end. Addiction is not a moral failing. It is a medical condition and poses a constant threat to health.”

A “Uniquely American Problem”

Nearly 10 million Americans misuse prescription opioids every year and at a rate far higher than comparable developed countries. Deaths due to opioid overdose in the United States are ten times more common per capita than in Germany and more than 20 times as frequent in Italy, for instance.

Much of this is down to the United States’ for-profit healthcare system. American private insurance companies are far more likely to favor prescribing drugs and pills than more expensive therapies that get to the root cause of the issue driving the addiction in the first place. As such, the opioid crisis is commonly referred to as a “uniquely American problem.”

Part of the reason U.S. doctors are much more prone to doling out exceptionally strong pain medication relief than their European counterparts is that they were subject to a hyper-aggressive marketing campaign from Purdue Pharma, manufacturers of the powerful opioid OxyContin. Purdue launched OxyContin in 1996, and its agents swarmed doctors’ offices to push the new “wonder drug.”

Yet, in lawsuit after lawsuit, the company has been accused of lying about both the effectiveness and the addictiveness of OxyContin, a drug that has hooked countless Americans onto opioids. And when legal but incredibly addictive prescription opioids dry up, Americans turned to illicit substances like heroin and fentanyl as substitutes.

Purdue Pharma owners, the Sackler family, have regularly been described as “the most evil family in America”, with many laying the blame for the hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths squarely at their door. In 2019, under the weight of thousands of lawsuits against it, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy. A year later, it plead guilty to criminal charges over its mismarketing of OxyContin.

Nevertheless, the Sacklers made out like bandits from their actions. Even after being forced last year to pay nearly $6 billion in cash to victims of the opioid crisis, they remain one of the world’s richest families and have refused to apologize for their role in constructing an empire of pain that has caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Instead, the family has attempted to launder their image through philanthropy, sponsoring many of the most prestigious arts and cultural institutions in the world. These include the Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, Yale University, and the British Museum and Royal Academy in London.

One group who are disproportionately affected by opioids like OxyContin, heroin and fentanyl are veterans. According to the National Institutes of Health, veterans are twice as likely to die from overdose than the general population. One reason for this is bureaucracy. “The Veterans Administration did a really poor job in the past decades with their pain management, particularly their reliance on opioids,” Hoh, a former marine, told MintPress, noting that the V.A. prescribed dangerous opioids at a higher rate than other healthcare agencies.

Ex-soldiers often have to cope with chronic pain and brain injuries. Hoh noted that around a quarter-million veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq have traumatic brain injuries. But added to that are the deep moral injuries many suffered – injuries that typically cannot be seen. As Hoh noted:

Veterans are turning to [opioids like fentanyl] to deal with the mental, emotional and spiritual consequences of the war, using them to quell the distress, try to find some relief, escape from the depression, and deal with the demons that come home with veterans who took part in those wars.”

Thus, if the Taliban’s opium eradication program continues, it could spark a fentanyl crisis that might kill more Americans than the 20-year occupation ever did.

Broken Society

If diseases of despair are common throughout the United States, they are rampant in Afghanistan itself. A global report released in March revealed that Afghans are by far the most miserable people on Earth. Afghans evaluated their lives at 1.8 out of 10 – dead last and far behind the top of the pile Finland (7.8 out of 10).

Opium addiction in Afghanistan is out of control, with around 9% of the adult population (and a significant number of children) addicted. Between 2005 and 2015, the number of adult drug users jumped from 900,000 to 2.4 million, according to the United Nations, which estimates that almost one in three households is directly affected by addiction. As opium is frequently injected, blood-transmitted conditions like HIV are common as well.

The opioid problem has also spilled into neighboring countries such as Iran and Pakistan. A 2013 United Nations report estimated that almost 2.5 million Pakistanis were abusing opioids, including 11% of people in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Around 700 people die each day from overdoses.

Empire of Drugs

Given their history, It is perhaps understandable that Asian nations have generally taken far more authoritarian measures to counter drug addiction issues. For centuries, using the illegal drug trade to advance imperial objectives has been a common Western tactic. In the 1940s and 1950s, the French utilized opium crops in the “Golden Triangle” region of Southeast Asia in order to counter the growing Vietnamese independence movement.

A century previously, the British used opium to crush and conquer much of China. Britain’s insatiable thirst for Chinese tea was beginning to bankrupt the country, seeing as China would only accept gold or silver in exchange. The British, therefore, used the power of its navy to force China to cede Hong Kong to it. From there, it flooded mainland China with opium grown in South Asia (including Afghanistan).

The effect of the Opium War was astonishing. By 1880, the British were inundating China with more than 6,500 tons of opium per year – the equivalent of many billions of doses. Chinese society crumbled, unable to deal with the empire-wide social and economic dislocation that millions of opium addicts brought. Today, the Chinese continue to refer to the period as the “century of humiliation”.

Meanwhile, in South Asia, the British forced farmers to plant poppy fields instead of edible crops, causing waves of giant famines, the likes of which had never been seen before or since.

And during the 1980s in Central America, the United States sold weapons to Iran in order to fund far-right Contra death squads. The Contras were deeply implicated in the cocaine trade, fuelling their dirty war through crack cocaine sales in the U.S. – a practice that, according to journalist Gary Webb, the Central Intelligence Agency facilitated.

Imperialism and illicit drugs, therefore, commonly go together. However, with the Taliban opium eradication effort in full effect, coupled with the uniquely American phenomenon of opioid addiction, it is possible that the United States will suffer significant blowback in the coming years.

The deadly fentanyl epidemic will likely only get worse, needlessly taking hundreds of thousands more American lives. Thus, even as Afghanistan attempts to rid itself of its deadly drug addiction problem, its actions could precipitate an epidemic that promises to kill more Americans than any of Washington’s imperial endeavors to date.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

“

“

The Worldwide Corona Crisis, Global Coup d’Etat Against Humanity

The Worldwide Corona Crisis, Global Coup d’Etat Against Humanity

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles