History of World War II: Operation Barbarossa, Analysis of Fighting, The Germans Surround Kiev and Leningrad

Part II

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

In the second half of August 1941, the German strategic plan in their invasion of the USSR was drastically altered. Most of Army Group Center’s armor was dispatched southward to the Ukraine, with the Wehrmacht’s advance on Moscow postponed temporarily.

By now, the Nazi Security Service was reporting on a “certain unease” and a “decline in the hopeful mood” of the German population. The quick triumph in the east they were assured of by Joseph Goebbels‘ propaganda had not arrived. The anxiety afflicting the German public was increased by letters sent home from Wehrmacht troops, many of which confirmed that the attack on the Soviet Union was not progressing as planned. There were also rising numbers of death notices of German soldiers in the newspapers.

Well-known German author Victor Klemperer, who was Jewish, wrote from Dresden with far-sighted accuracy on 2 September 1941,

“The general question is whether things will be decided in Russia before the wet season in the autumn. It does not look like it… One is counting how many people in the shops say ‘Heil Hitler’ and how many ‘Good day’. ‘Good day’ is apparently increasing”.

Hitler himself “realized that his plans for a Blitzkrieg campaign in the east had failed” by early August 1941, German historian Volker Ullrich wrote in the second part of his biography on Hitler. Two weeks later on 18 August, Hitler said outright to Propaganda Minister Goebbels that he and the German generals had “completely underestimated the might and especially the equipment of the Soviet armies”.

Russian tank numbers, for example, were more than twice greater than Nazi intelligence had originally estimated, and the Red Army itself was much larger than predicted. Seven weeks into the invasion, on 11 August 1941 General Franz Halder, Chief-of-Staff of the German Army High Command (OKH), stated in his diary, “At the start of the war, we anticipated around 200 enemy divisions. But we have already counted 360”.

Yet, as September 1941 began, it seemed quite possible that Hitler was pulling off another telling victory to silence his commanders’ doubts. In dry weather with clear skies overhead Panzer Group 2, led by General Heinz Guderian, captured the northern Ukrainian city of Chernigov on 9 September 1941, just 80 miles north of the capital, Kiev. Guderian’s panzers drove east, thereafter, to take the long Desna Bridge at Novgorod Severskiy.

Colonel-General Ewald von Kleist’s four panzer divisions, belonging to Army Group South, rolled northwards to link up with Guderian’s armor. It was becoming obvious to Soviet military men that the Germans were implementing a gigantic pincers movement, which was aimed at cutting off all of the Russian armies within the Dnieper Bend and, in doing so, surrounding Kiev. The 58-year-old Marshal Semyon Budyonny, leading the Soviet Southwestern and Southern Fronts, could see this clearly. He pleaded in vain with Joseph Stalin to let him retreat to the Donets River.

From early on Stalin had refused to allow Kiev to be abandoned. His prominent commander Georgy Zhukov warned him, as early as 29 July 1941, that the exposed Ukrainian capital should be forsaken for strategic purposes. An angry Stalin replied to Zhukov “How could you hit upon the idea of surrendering Kiev to the enemy?” Zhukov said throughout August that he “continued to urge Stalin to advise such a withdrawal”. On 18 August, Stalin and the Soviet Supreme High Command (Stavka) issued a directive ordering that Kiev must not be surrendered. Stalin could not bear to give up the Soviet Union’s third largest city without a fight.

At the end of August 1941, the Wehrmacht had forced the Red Army back to a defensive line at the Dnieper River. Kiev lay vulnerable at the end of a long salient. Stalin then compounded his original strategic mistake, by reinforcing the area around Kiev with more Red Army divisions.

On 13 September 1941 Major-General Vasily Tupikov, in the Kiev sector, compiled a report outlining how “complete catastrophe was only a couple of days away”. Stalin responded, “Major-General Tupikov sent a panic-ridden dispatch… The situation, on the contrary, requires that commanders at all levels maintain an exceptionally clear head and restraint. No one must give way to panic”.

The following day, 14 September, von Kleist and Guderian’s panzers met at the Ukrainian city of Lokhvytsia, 120 miles east of Kiev. The trap was sealed. Budyonny’s troops fought frantically to extricate themselves but these efforts failed. As also did the Russian attacks coming from further east, which were attempts to rescue the doomed 50 Soviet divisions encircled in the Dnieper Bend.

Kiev fell to the Germans on 19 September 1941, and by the time the fighting died down on 26 September, 665,000 Soviet troops surrendered, the better part of five armies. This was the largest surrender of forces in the field in military history. The Soviets further lost 900 tanks and 3,500 guns. Total Red Army personnel losses in the Kiev area, including casualties, came to 750,000 men. Among the dead was Tupikov who, as mentioned, had tried to warn the Soviet General Staff about the calamity that was set to unfold.

English scholar Geoffrey Roberts wrote, “On 17 September Stavka finally authorized a withdrawal from Kiev, to the eastern bank of the Dnepr. It was too little, too late; the pincers of the German encirclement east of Kiev had already closed”.

After the loss of Kiev, Stalin was “in a trance” according to Zhukov and it understandably took him some days to recover. At this point three months into the Nazi-Soviet war the Red Army had, altogether, lost at least 2,050,000 men, while the Germans had suffered casualties of less than 10% of that number, 185,000 men, the British historian Evan Mawdsley noted. The 185,000 figure still amounted to a higher number of casualties inflicted on the German Army (156,000) in the Battle of France, and the fighting on the Eastern front was of course far from over.

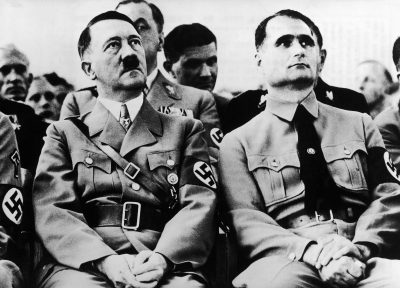

On 23 September 1941 Goebbels visited Hitler at the latter’s military headquarters, the Wolf’s Lair, located near the East Prussian town of Rastenburg. With Kiev having just fallen, Goebbels observed that Hitler looked “healthy” while he was “in an excellent mood and sees the current situation extremely optimistically”.

Hitler took personal credit for taking Kiev, in which he had previously ignored the German commanders’ protests, as they were adamant the advance on Moscow should resume. Hitler told Goebbels that Army Group South would continue marching, in order to capture the USSR’s fourth largest metropolis, Kharkov, in eastern Ukraine, over 250 miles further east of Kiev; and after that they should move on to take Stalingrad, another 385 miles further east again. One of these two goals was reached, with Kharkov falling to the German 6th Army on 24 October 1941. Northwards, Hitler also wanted Leningrad to be utterly subdued, Soviet Russia’s second biggest city.

In his memoirs Marshal Zhukov wrote, “Before the war, Leningrad had a population of 3,103,000 and 3,385,000 counting the suburbs”.

On 8 September 1941 Army Group North had penetrated these suburbs, with the German panzers just 10 miles from the city. So officially began the terrible Siege of Leningrad. During 10 September, Hitler informed lunch guests of his intentions regarding Leningrad, “An example should be made here and the city will disappear from the face of the earth”.

Already on 8 September, the Germans captured the town of Shlisselburg on the south shore of Lake Ladoga. A week later Slutsk (Pavlovsk) fell in Leningrad’s outer suburbs, as too did Strelna, close by to the south-west of Leningrad. To the north, the Finnish Army advanced to within a few miles of Leningrad’s northernmost suburbs and the city was now surrounded.

The German Armed Forces High Command (OKW), with Hitler’s agreement, ordered that Leningrad was not to be taken by storm; but would be bombarded from the air by the Luftwaffe, while the city’s residents were to be starved to death through military blockade. On 12 September 1941 the largest food warehouse in Leningrad, the Badajevski General Store, was blown up by a Nazi bomber aircraft.

Moreover, heavy German weaponry and artillery was ominously lined up on the ground, across Leningrad’s outskirts. The German guns had sufficient range to strike every street and district of the city, meaning that virtually no house or apartment block in Leningrad was safe, a constant terror for its inhabitants.

Following Hitler’s Directive No. 35 of 6 September 1941, Colonel-General Erich Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4 was moved away from the Leningrad region on 15 September. It was transferred to the central front for the renewed march towards Moscow. The halting of the German advance on Leningrad, at a time when it appeared on the cusp of success, meant in the end that the city was not captured at all. The 41st Panzer Corps commander, Georg-Hans Reinhardt, had been confident that Leningrad would be taken. Reinhardt was sketching various routes on a map of Leningrad for the advance into the city, when he was ordered to cease his approach.

Nor was Leningrad fully encircled in wintertime when the water froze on Lake Ladoga, by far Europe’s largest lake. The Russians were soon able to traverse Lake Ladoga with vehicles carrying food and supplies, though they were regularly assaulted by the Luftwaffe. Fortunately, a large proportion of Leningrad’s inhabitants escaped from the city. Zhukov wrote, “As many as 1,743,129, including 414,148 children, were evacuated by decision of the Council of People’s Commissars between June 29, 1941 and March 31, 1943”.

The Germans were never able to regain the momentum in their initial march towards Leningrad. In November 1941 an offensive to join forces with the Finns east of Lake Ladoga failed. Through December the Germans were forced to retreat to the Volkhov River, about 75 miles south of Leningrad. All efforts to destroy the Soviet bridgehead at Oranienbaum, near to the west of Leningrad, were unsuccessful.

Leningrad was helped in its defense by the city’s geographical position, between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. In comparison to Kiev or Moscow, Leningrad was considerably easier for the Red Army to defend. Leningrad’s western approaches were guarded by the Gulf of Finland, its northern part by the narrow strip of land called the Karelian Isthmus, its south-eastern section by the upper Neva River; while much of the area bordering the city to the south comprised of marshy terrain, which the Germans could not wade through.

Stalin placed even more importance in Leningrad’s survival than Kiev. In a telegram of 29 August 1941 sent to his Foreign Affairs Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, an anxious Stalin wrote, “I fear that Leningrad will be lost by foolish madness and that Leningrad’s divisions risk being taken prisoner”. If the city was captured by Hitler’s forces, it would enable the enemy to make a flanking attack northward on Moscow. The loss of the city that bore Lenin’s name, the founder of Soviet Russia, could only constitute a serious blow to Russian morale and a great triumph for the Nazis. The Soviet Union would be deprived of an important center of arms production were Leningrad taken.

On 10 September 1941, Stalin ordered Stavka to appoint Zhukov as commander of the new Leningrad Front. Zhukov, who possessed great ability and energy, helped to stiffen the defenses around Leningrad, forbidding Soviet officers to sanction retreats without written orders from the military command. By late September 1941, the Leningrad front had stabilized.

More than a million Soviet troops would be killed in the Leningrad region, over the next two and a half years. During that time 640,000 of Leningrad’s inhabitants died of starvation, and another 400,000 lost their lives due to either illnesses, German shelling and air raids, added to those who perished in the course of evacuations, etc.

The Siege of Leningrad was endured mainly by its female residents. Most of Leningrad’s male populace were fighting in the Soviet Army or had joined the People’s Militia, divisions of irregular troops. Leningrad’s heroic resistance helped to tie down a third of the Wehrmacht’s forces in 1941, which assisted in Moscow being saved from German occupation.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Sources

Marshal of Victory: The Autobiography of General Georgy Zhukov (Pen & Sword Military, 3 Feb. 2020)

Volker Ullrich, Hitler: Volume II: Downfall 1939-45 (Vintage, 1st edition, 4 Feb. 2021)

Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov (Icon Books, 2 May 2013)

Clive N. Trueman, The Siege of Leningrad, The History Learning Site, 15 May 2015

Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953 (Yale University Press; 1st Edition, 14 Nov. 2006)

Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945 (Hodder Arnold, 23 Feb. 2007)

Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 2nd edition, 3 April 1985)

Weapons and Warfare, Heavy Artillery at Leningrad