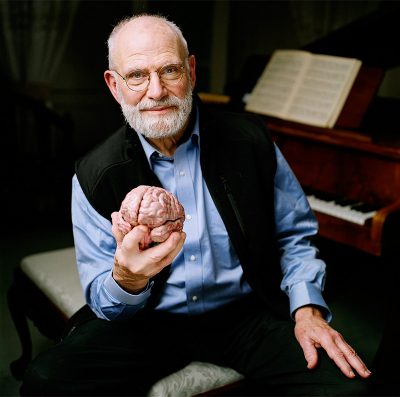

Oliver Sacks, the “Neurological Philosopher”

Oliver Sacks, the “neurological philosopher”, did a “different sort of medicine on behalf of chronic often warehoused and largely abandoned patients.” It combined art and science. Lawrence Weschler, in a new biography, says Sacks was from “the period before the science and the humanities split apart”.[i]

But they didn’t just “split apart”. They were torn apart. Weschler doesn’t name the ideology responsible.

It didn’t convince everyone. Some saw through it, especially in the global South. Like Sacks, they wanted to know persons. Sacks had the “audacity to imagine that there might in fact be ongoing life persisting deep within those long-extinguished cores.” A nun at Little Sisters in the Bronx said:

“Everyone who reads his [clinical] notes sees the patients differently …. Most consultants’ notes are cut and dried, aimed at the problem with no sense of the person …. With him the whole person becomes visible.”

European philosophers separated science and the humanities. They invented the “fact/value” distinction, between what is and what ought to be. They said knowledge of the latter doesn’t exist, or might not exist. Cuban scholar Armando Hart says anyone who cares about global justice in the 21st century should notice the damage done to the world by European philosophy. He meant liberalism. It denied truth – or at least put it in doubt – about humanness.

It made sense for those who defined humanness.

Sacks called himself a “clinical ontologist”. His science was about being, but not in the abstract. He meant the being of people, the “living statues” who were the subject of his masterpiece, Awakenings, later a film and a one-act play. He saw their stillness as active. Being as doing. Sacks responded to “philosophical emergencies”. It was part of his science.

There is an expectation in the North that Philosophy is useless, that it is at best a luxury for elite academics who live in universities and speak in complicated ways, only to each other. But Gramsci said that if you don’t understand the ideas explaining ideas, making them plausible, new ideas are ineffective because they are understood in terms of the old, mitigating their effect.

Weschler presents Sacks (affectionately) as odd without naming the ideology that makes him odd. Yet Sacks’ view was not odd.

Tolstoy knew it. Lenin commented that Tolstoy’s ideas were ‘bourgeois’ but his writing revolutionary. It’s because artists, unlike philosophers, articulate the human condition. And human emancipation is impossible without knowing the human condition.

Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov (War and Peace) reverses the popular myth of instrumental rationality. Pierre “did not wait, as before, for personal reasons, which he called people’s merits, in order to love them, but love overflowed his heart, and, loving people without reason, he discovered the unquestionable reasons for which it was worth loving them”.

Tolstoy calls it “insanity”. Pierre feels love, and as a result, has reasons. He doesn’t have purpose and from that get reasons. Indeed, he has no purpose. He has feeling, which Tolstoy describes as love. Pierre’s feelings explain what matters to him; it is not what matters to him – purpose – that explains his feelings: of energy, for instance, or importance.

In theory, Pierre’s approach is suspect. The 20th century philosopher, Che Guevara, said,

“At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love”.

The risk is real because love is not rational. Feelings are not rational. Love cannot guide because it is a feeling.

But this is ideology. And Guevara rejected it. He argued against the splitting of mind and body, feeling and intellect, art and science, faith and proof. Moreover, he followed a whole tradition of thinkers, not all revolutionaries, who also so argued. They wanted human, not just political, liberation, and they needed to know what “human” meant. They rejected liberalism because it didn’t make sense.

It doesn’t make sense, and this is known. But it persists because liberal intellectuals like Weschler don’t bother with philosophy. He admires Sacks, and names repeatedly the philosophers Sacks cared about. But he doesn’t do the work Gramsci said is essential to criticism: explaining the ideas that make other ideas plausible, even when they’re not, and it’s known.

It is significant that Pierre comes to his “insanity” after confronting death. He is a prisoner of Napoleon and is lined up to be executed. He watches the young man before him as he is shot dead. He notices how he crosses his leg as he stands, waiting to die. It is an ordinary gesture, but striking in the face of death, precisely for being ordinary.

Pierre expects to die. There’s no storytelling, no generating of meaning “from within” aimed at some abstraction called “self” or “purpose”. Herein lie what Tolstoy calls “unshakeable foundations”.

It’s mental silence: experience of the here and now, without expectations. A quiet mind is the exercise of one’s faculties – to see, hear, touch, smell, remember – without jarring, uncontrollable, mostly illogical mental conversation. Quietness fascinated Sacks.

He didn’t like Sartre’s “uncalmness”, his “chargedness”. Weschler mentions this but doesn’t explain. But we know Sacks didn’t like his own 1960s theory of behaviour because it didn’t account for “peacefulness, enoughness, satiety, repletion.” Sacks wouldn’t have liked Sartre because Sartre’s existentialism can’t handle stillness.

Liberal philosophy generally can’t handle it. It doesn’t fit with the liberal, capitalist “man of action”, the unrealistic individual with “power to seize their destiny”. Philosophers invented the “fact/value” distinction, suggesting knowledge about existence – what is – but not about what it means to be human.

It doesn’t respect science because it doesn’t respect cause and effect. But this is known, intellectually. It’s been argued for more than half a century in analytic philosophy of science. In practise, though, philosophy of science has no effect beyond its narrow specialization.

Sacks did have effect. His effect could be made more useful, though, if its real target were named and fully denounced.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Susan Babbitt is author of Humanism and Embodiment (Bloomsbury 2014). She is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Note

[i] And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? A Biographical Memoire of Oliver Sacks (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019).

See review https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/and-how-are-you