Oil and Gas and “The Climate-Change Fakery”: The Constitutional Underpinnings of the Natural Resource Wars Between the Canada and Alberta Governments

Part II

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Read Part I:

Oil and Gas and Climate Change Fakery

By , September 07, 2023

The British North American Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982

Canada’s Constitution was formulated in two big spurts. One led to the ratification of the British North American Act in 1867 by the Mother Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Scotsman John A. Macdonald was the primary figure who both envisaged and implemented the plan to pull together into a single polity all the British colonies and corporations in North America. His plan was to edify and elaborate the British Empire, not to break free from the imperial connection as had been done by the founders of the United States. By sharing in the power of the British Empire, the makers of the Dominion of Canada were able to withstand the pull of the United States whose population and economy have historically been about ten times that of the Canadian Dominion.

The job of creating a coast-to-coast-to-coast Dominion in North America was extremely ambitious. It included the transformation of the financial and territorial organization of the Hudson’s Bay fur trade company into the structure of finance and privatized land integral to the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company.

Formed in 1858, the Pacific Coast colony of British Columbia joined the Dominion in 1871 based on the promise that the government of Canada would build a railway to eastern and central Canada through the legally-transformed Hudson’s Bay Company lands. The overall project succeeded, resulting in the creation of the second largest country in the world.

The main outlines of the plan were successfully implemented over a period of about 20 years between 1864, when the Fathers of Confederation met in Quebec City, and 1885, when the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed. At the Quebec Conference many plans were mounted leading to the enactment in 1867 by the British Parliament of the British North American Act.

The British North American Act created the Dominion of Canada, originally a confederation of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec. Ontario and Quebec were previously known as Upper and Lower Canada before being amalgamated in 1840 as the Province of Canada.

Lower Canada, a seed of the current province of Quebec, was and is predominantly inhabited by French-speaking people whose Roman Catholic ancestors had founded and developed New France, a colony sometimes described as Canada. Often the inhabitants of New France referred to themselves as canadiens, a name that still describes Montreal’s hockey team. So the original Canada—-a jurisdiction that has gone through many incarnations— is much older than the United States of America.

The second spurt of constitution making was initially connected to the twists and turns of the Quebec independence movement, a movement that Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau enthusiastically fought against. This movement for Quebec independence outside the bounds of English-speaking Canada had culminated in 1980 in a referendum organized by Premier René Lévesque, the founder and leader of the Parti Québécois.

Canada’s Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, led the campaign to defeat Lévesque’s YES campaign to bring about Quebec’s independence. In the campaign led by Trudeau, he promised Quebeckers that, with their NO vote, they would be setting in motion a positive renewal of Canadian federalism. The renewal was to be expressed by coming up with the contents of what was supposed to be Canada’s last request to the imperial Parliament in Great Britain. The core of that request was to move to Canada the means of making and amending Canada’s own constitution.

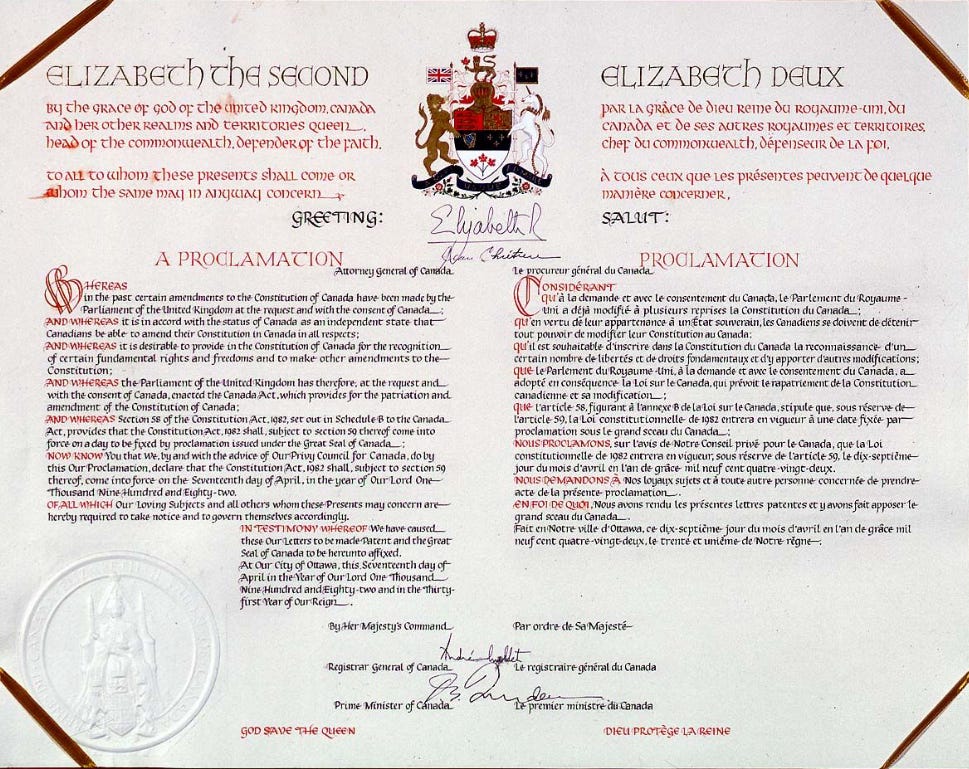

This procedures addressed the problem that so many of Canada’s core institutions of government had deep British roots that only the government of Great Britain had the legal means of changing. This last resort to the British Parliament was sometimes referred to as the “patriation” of Canada’s constitution. As we shall see, this vehicle of patriation, the Constitution Act, 1982, became a platform for many instruments meant to renovate the legal design of Canadian federalism. One of the ironic outcomes was to widen the legal divide between the National Assembly of Quebec and the governments of the other Canadian provinces.

Trudeau and his constitutional lieutenant, Jean Chrétien, went to work on this project with a directive from the Supreme Court that they would need a significant measure of provincial support if their mission was to succeed.

With this guidance from Canada’s top judges, Trudeau and his Team went to work to induce provincial premiers to buy into the patriation initiative. By late 1982 Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and 9 of the 10 provincial premiers came up with a document they all backed. The text of the Constitution Act, 1982 was ratified by the Parliament of Canada, the Parliament of Great Britain, and by the legislatures of nine Canadian provinces.

The whole procedure was subsequently ratified by Queen Elizabeth in a signing ceremony on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill.

The fact that Quebec continues to be part of Canada while staying outside the ratification process of Constitution Act 1982 sets a precedent that Alberta might choose to adopt or adapt in some fashion.

Could the people and government of Alberta withdraw from some elements of the Canadian Constitution while, like the people and government of Quebec, continuing to be part of those aspects of the Canadian federation that serve their purposes? Some Albertans have been carefully studying Quebec’s independence movement for examples of how Canada’s only predominantly French-speaking province gained such a sweet deal for itself in Confederation.

One element of the Constitution Act 1982 is known as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. We can now see this Charter as a farcical construction that provided zero protections for Canadian citizens during its first major test beginning with the forced imposition of multiple COVID restrictions and mandates in 2020. See this.

Another part of the Constitution Act, 1982, amended the British North American Act of 1867. These new provisions, to which Quebec never agreed, added a new subsection to section 92 of the BNA. Section 92 (A) of the altered Constitution Act, 1867, explicitly details a list of Natural Resource powers, rights and responsibilities that adhere to the provincial legislatures. See this.

The new section, 92 (A), states,

Laws respecting non-renewable natural resources, forestry resources and electrical energy

92A (1) In each province, the legislature may exclusively make laws in relation to

(a) exploration for non-renewable natural resources in the province;

(b) development, conservation and management of non-renewable natural resources and forestry resources in the province, including laws in relation to the rate of primary production therefrom; and

(c) development, conservation and management of sites and facilities in the province for the generation and production of electrical energy.

Subsection 2 and 3 of 92 (A) involves the provincial export within Canada of electricity and non-renewable resources. In the subsections below there is a stipulation that the imperative of Parliament to govern trade and commerce must “prevail” when it comes to matters pertaining to this export.

Export from provinces of resources

(2) In each province, the legislature may make laws in relation to the export from the province to another part of Canada of the primary production from non-renewable natural resources and forestry resources in the province and the production from facilities in the province for the generation of electrical energy, but such laws may not authorize or provide for discrimination in prices or in supplies exported to another part of Canada.

Authority of Parliament

(3) Nothing in subsection (2) [of 92 (A)] derogates from the authority of Parliament to enact laws in relation to the matters referred to in that subsection and, where such a law of Parliament and a law of a province conflict, the law of Parliament prevails to the extent of the conflict.

It is very clear that those in Canada and Great Britain who drafted the British North American Act meant the Dominion government, now dubbed the federal government, to prevail over provincial jurisdiction. The Dominion was endowed with a Parliament whereas as the provinces have legislatures.

Similarly, the Canadian Crown was embodied in the person of a Governor-General whereas the embodiments of the provincial Crowns were described as Lieutenant-Governors. This subordination of provincial legislatures is signified by the BNA Act’s investment in Parliament of the power to disallow provincial legislation. This provision has been used over 100 times by the Canadian government.

Parliament still has the legal authority to disallow provincial legislation. Indeed, some Canadians were recently faced with the spectacle of a CBC journalist trying to bully and badger Trudeau’s intergovernmental Affairs Minister, Dominic LeBlanc, into unleashing the federal power of the disallowance provision on the Alberta Sovereignty Act.

Canada’s CTV Television network gave University of Alberta Law Professor, Eric Adams, a segment to give his explanation of why he thinks the Alberta Sovereignty Act is a disaster for Canada. According to Prof. Adams, everything was going great in Canada until Danielle Smith showed up as premier. Our courts were just humming away dispensing impartial justice by the truckload as all Canadians were perfectly content to just sit back and trust the politically-appointed judges to sort out problems, including jurisdictional disputes between Ottawa and the provinces.

From his comfortable academic perch as one of Ottawa’s Liberal fixers in Alberta’s capital, Adams seems uncomprehending of the reality that many in Canada have come to deeply distrust the judiciary since it joined so intimately with the political branch of government in 2020. Justice Minister Lametti and and Chief Justice Wagner formally collaborated in highly inappropriate ways with the effect of eliminating the protections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms just when we needed them the most. When the issue of the Charter finally came before the Federal Court in the the autumn of 2022, a Trudeau-appointee declared that the issue of Charter rights had become “moot.” See this.

Adams speaks as an apologist for the legal establishment including the discredited judiciary. With blasé disregard of the unusual nature of these times, he speaks from the podium of a University that, like most so-called centres of higher learning, went along uncritically with the mass jabbing of students, staff and faculty. The cumulative worldwide effects of this globally-replicated procedure, have killed and maimed many millions. This reality, however, will not be reported by the likes of CBC or CTV, networks that censor many voices that do not conform to increasing dangerous and demented uniparty line.

The big media cartels in Alberta did not only reported on the Alberta’s recent provincial election. They participated in the campaign as partisan proponents of NDP leader Rachel Notley. Thus when Notley lost to Danielle Smith, the media also lost its own partisan campaign which continues nevertheless, through, for instance, made-for-TV smear campaign to try to deprive the Alberta Sovereignty Act of public support.

Who Takes Ownership of the Indian Lands? The Dominion Government or the Provincial Governments of Canada?

Constitutions can be made by politicians and sometimes by citizens in referendums. In many cases it is, however, judges that step in to sort out disagreements which stop short of civil war. From 1867 until 1949, the highest court in arbitrating constitutional disagreements between the Dominion and provincial governments was the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the House of Lords of the British Parliament. See this.

Especially under Lord Watson and then under Lord Haldane, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) tended to edify the authorities and powers of provincial governments. In doing so the imperial jurists tended to side against the claims and assertions of the Dominion Government. One of the seminal rulings of the JCPC on the BNA Act was handed down in 1888.

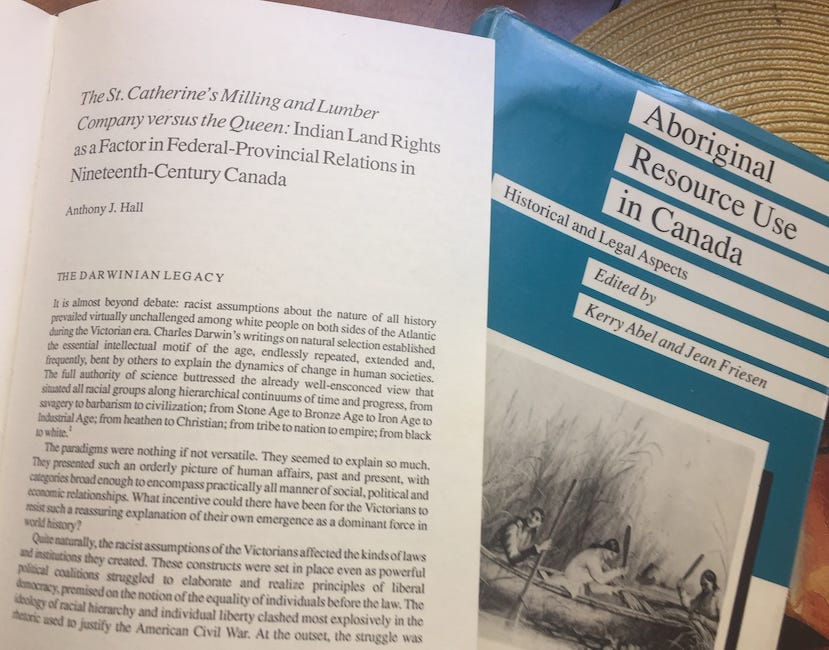

The St. Catherine’s Milling and Lumber Case tested the claims of the Canadian and Ontario governments when it came to the issue of the ownership of lands subject to the authority of section 91(24) of the BNA Act. This provision assigns to the Dominion Parliament jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians.”

Prime Minister John A. Macdonald decided that section 91(24) enabled the Dominion government to assign some land rights to the St. Catherine’s Milling Company. These land rights could be traced back to an exchange of commitments in the making of Treaty #3 in 1873 between agents of Queen Victoria and Ojibway leaders in the Kenora era on the western boundaries of Ontario. Under Premier Oliver Mowat, the government of Ontario challenged the legitimacy of this transaction by charging the Milling Company with a crime for cutting trees that did not belong to them. This Company was defended by lawyers paid for and also representing the government of Canada.

The provincial government won the case on the basis of the arguments put forward by former Liberal Party Leader, William Blake. Citing a series of cases going back to the Crusades, Blake asserted that the Indians were subject to the old doctrine that when new territories are annexed, “the laws of the infidel are abrogated, for that they be not only against Christianity, but against the law of God and nature.”

Blake went further. He maintained that Indians in Canada were such an “inferior race,” in such an “inferior state of civilization” that they “have no government and no organization, and cannot be regarded as holding land.” Since property is a “creature of law,” then Indians characterized as having “no government and no organization,” could not be regarded as owners of any solid title to their ancestral lands.

The JCPC did not go as far as to sanction all of Blakes’ arguments in agreeing to the plantiff’s position that The St. Catherine’s Milling Company and the Dominion government of Canada had together violated the law. The JCPC did recognize the rights of Indians to a very shallow usufuctuary interest in their own ancestral lands. They could use the land but now own it. Gradually the idea developed that the Indian right to land was a “burden” on Crown title. This burden lies was said to lie on the metaphorical surface of a deeper proprietary sovereignty that Canada inherited from the original North American claims of the British imperial monarchy.

No living Indian people were afforded any status whatsoever to participate in the constitutional dispute in the late 1880s between the governments of Canada and Ontario. The Indians were excluded from the constitutional proceedings concerning the delegation of authority to govern Indians and the lands said to be “reserved” for Indians. This exclusion confirmed a pattern that carried on for slightly more than a century.

One feature of this exclusion was that, until the early 1960s, registered Indians in Canada were excluded from the rights and responsibilities of Canadian citizenship. They could not vote, run for office, own real estate, borrow money from banks, sign contracts or hold jobs that required them to sign documents.

A key constitutional provision that came under close judicial scrutiny in the St. Catherine’s Milling case was section 109 of the BNA Act. That provision asserts,

109. All Lands, Mines, Minerals, and Royalties belonging to the several Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick at the Union, and all Sums then due or payable for such Lands, Mines, Minerals, or Royalties, shall belong to the several Provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick in which the same are situate or arise, subject to any Trusts existing in respect thereof, and to any Interest other than that of the Province in the same.

Section 109 is silent on the question of the status of lands that would later form the basis of new provinces. The BNA of 1867 was silent, for instance, on the status of the new jurisdictions that would be carved from the vast fur trade domain about to be acquired by the Dominion from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869-70. The new provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan, were created in 1905 by the authority of the Dominion of Canada.

Like the province of Manitoba created in 1871 by the Dominion of Canada on some of the land it had recently acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company, Alberta and Saskatchewan were conceived of as junior provinces. These new polities did not acquire formal title to the lands and natural resources on which they sat until 1930. In 1930 the governments of Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan obtained from the Dominion government proprietorship over lands and resources within their boundaries.

One could argue that what can be given can also be taken away by the same party that originally did the giving. In normal times the prospect of the federal government taking back the natural resources in the three prairie provinces, would be almost inconceivable. These times, however, are not normal.

The Constitutional Legacy Of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in the Transformation of the Legal Status of Natural Resources in Canada

The outcome of the St. Catherine’s Milling case did not permanently shut down the raising of various constitutional issues concerning Aboriginal peoples and their lands. What the ruling did do, however, was to contribute significantly to the sidelining of Native peoples from the core institutional mechanisms of law, politics, and economics during the crucial century in Canada’s remaking.

During this century of much of Canada was transformed from a fur trade preserve for the Indian people to a realm favouring the commercial enterprises of European immigrants and their descendants.

Some aspects of legacy of the St. Catherine’s Milling case do not stand up well to the test of time. The positions advanced on behalf of the Ontario government by Edward Blake were similar to those supporting the ownership of slaves in the era before US Civil War. They were similar to the justifications in the 1830s of the Trail of Tears, a uprooting and forced march of Cherokees from Georgia to a new Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

The Trail of Tears was part of a larger scheme hatched by US Thomas Jefferson and attempted by President Andrew Jackson. This scheme aimed to make the Mississippi the dividing point in a continent-wide system of Indian-Non-Indian apartheid. A smaller-scale replication of this policy was attempted in British North America. The author of the policy attempted to draw the Native peoples from the farming areas of Upper Canada to a segregated Indian Territory on Manitoulin Island on Lake Huron.

Throughout the twentieth century there was much discussion about the Aboriginal title to lands and resources in British Columbia. In British Columbia, Church of England missionaries worked closely with the political organizations of Aboriginal peoples to demand that the principles of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 should be applied in Canada’s westernmost province. Officials of the Anglican Church pursued this goal on the understanding that the head of their Church, who was also the British sovereign, had inherited special responsibilities to protect the rights and territorial interests of the Aboriginal peoples in British North America.

Coastal Salish People as They Were Before the Creation of British Columbia

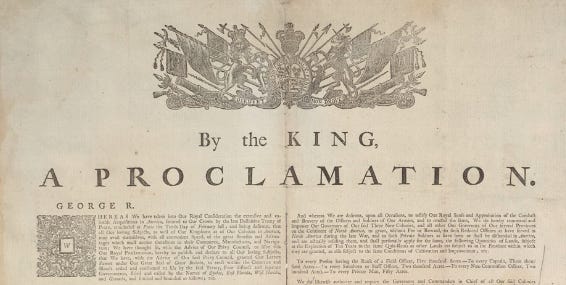

Already in the proceeding of the St. Catherine’s Milling case, an understanding began to develop that the reference in the British North America Act to “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians” repeated the constitutional language introduced by King George III in the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The Indian provisions of the Royal Proclamation opened up a split among settlers in the Anglo-American colonies that helped fuel a secessionist movement. This rise of this movement was a major factor in the founding of the United States of America in 1776 and 1783.

The King’s constitutional pronouncement in 1763 outlined new jurisdictions and procedures to govern the North American lands recently acquired from France. Besides creating the fourteenth British North American colony of Quebec, King George created a huge area in the eastern portion of the Mississippi Valley and in the Great Lakes area to be “reserved for the Indians as their hunting grounds.”

After the USA was created, this phrase in the Royal Proclamation continued to describe much about the legal nature of the large portion of North America that continued under the rule of the British imperial government. In the era of New France and in the era of British imperial Canada before 1867, the elaborate exchanges between Native peoples with Scots and canadien traders were essential to to the health of Canada’s political economy.

From the early 1800s until 1929, treaties were negotiated with the Aboriginal peoples in accordance with the Royal Proclamation’s requirement that Crown agents were required to obtain Indian consent before new areas were opened for non-Indian settlements and businesses.

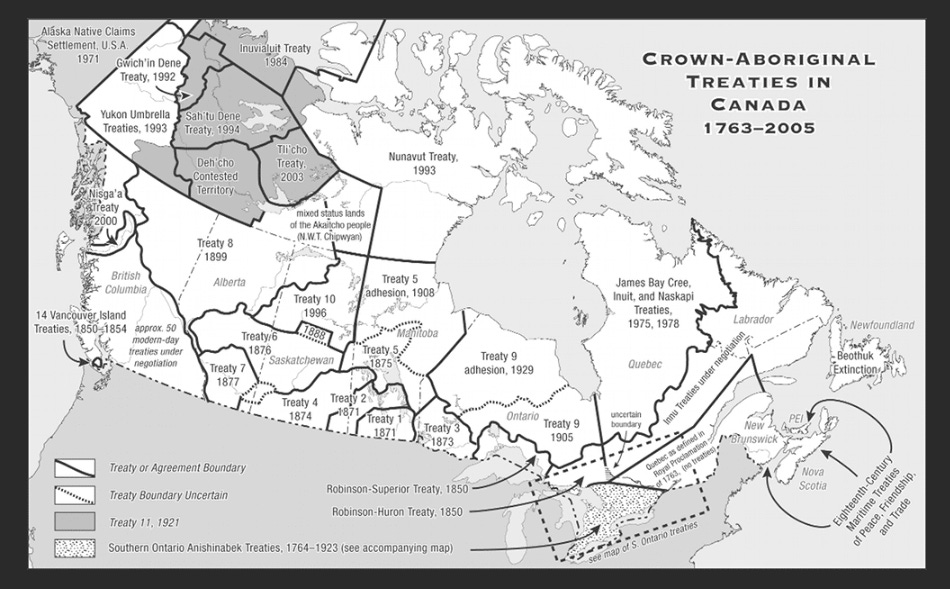

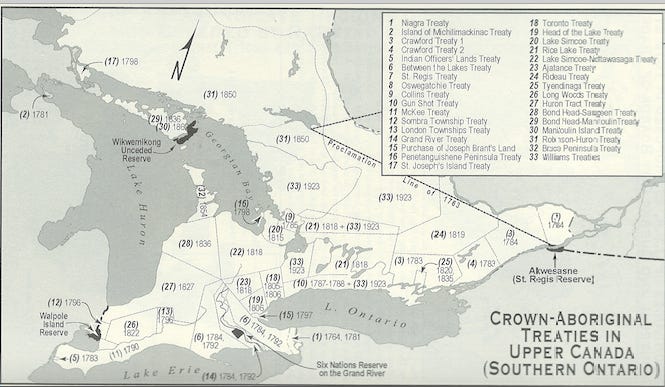

Maps by Anthony Hall, Originally published in Hall, The American American Empire and the Fourth World (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University, 2004)

Plucked from its original geographic setting, the Royal Proclamation’s procedures were widely applied from the banks of the Ottawa River the heights of the Rocky Mountains marking the BC-Alberta border. In spurts of activity agents of the Crown negotiated treaties with Aboriginal peoples.

Some would say that those treaties, even with all their shortcomings, did not extinguish Aboriginal title but rather formalized Canada’s recognition of an unextinguishable Aboriginal estate in Canada to exist for as long as the sun shines and the rivers flow. But when has the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, whose history is tied up with the negotiation of Crown-Aboriginal treaties, ever enforced this principle?

By the 1970s the push to apply the Indian provisions of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 began to gather traction in British Columbia. A crucial step in this direction was taken when the of Anglican Church in British Columbia and the Nisga’a Indians of the Nass River Valley retained Thomas Berger as their lawyer.

Together the partners set in motion legal and political initiatives that resulted in the making of the first Crown-Aboriginal treaty in Canada’s westernmost province. It’s coming into force in 1998 renewed the most prolonged Covenant Chain of constitutional enactments in North America.

The extension of the process of making Crown-Aboriginal Treaties to BC drew on constitutional traditions of Canada far older the British North America Act of 1867. The act of making modern-day treaties with Aboriginal peoples has helped shape the nature of Canada’s institutional growth in Northern Quebec, the Inuit realm of Nunavut, in Yukon in what remains of the North West Territories.

See Anthony J. Hall, “A Note on Canadian Treaties,” on Tom Molloy, The World Is Our Witness: The Historic Journey of the Nisga’a into Canada (Calgary: Fifth House, 2000)

Preparing the Canada Act for a Final Ritual of Ratification by the British Parliament

While in the midst of Canada’s reclamation of the constitutional principles and procedures of the Royal Proclamation, the federal delegation led by Pierre Trudeau entered into final negotiations with the delegations of the nine provincial delegations. The Quebec delegation of René Lévesque was not invited to take part in the negotiation in November of 1981 of an instrument to “patriate” the constitution from Great Britain to Canada.

On November 5 a draft of the document meant to be put before the British Parliament as the Canada Act, was introduced Canadian public. When Canada’s First Ministers had initiated the final negotiations, the text contained a provision that the “Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

This provision, one inserted into the proceedings by the Aboriginal wing of Canada’s NDP Party, was dropped from the text in the last minute alterations. A sharp focus on this attempted hatchet job, exposes much about the volatility of Aboriginal Affairs in the current structures of federal-provincial relations.

In Canada, Aboriginal issues should not be treated as a footnote to the big issues of constitutional law. Interactions with Native peoples on Canada’s expanding resource frontiers have insinuated their way into many facets law and politics including the dynamics of how federal-provincial relations on Energy Policy are unfolding now.

The placing of “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians” under federal jurisdiction threatens the proprietary treasure trove of natural resources created for Canada’s provinces by section 109 of the British North America Act. Section 109 acknowledges the basis of the provincial claims to “lands, mines, minerals and royalties” except those “subject to any trusts existing in respect thereof.” An obvious basis for one such “trust” would be the federal responsibility to preserve and safeguard “lands reserved for the Indians.”

The idea of a federal responsibility to safeguard Indian lands and resources represents a significant threat to some proponents of the provincial rights movement. Probably there is no provincial premier who has felt more menaced by section 91(24) of the British North American Act than Alberta’s former Premier, Peter Lougheed. In the final phase of the negotiation of the text of the Constitution Act, 1982, Lougheed led the demand by the nine provincial premiers to remove the provision affirming Aboriginal and treaty rights. The provincial premiers were so intent on extinguishing the rights of Aboriginal peoples they made this erasure the final condition for signing the patriation deal.

Given the absence of any Aboriginal representation on the final night of negotiations, the responsibility was clearly on the shoulders of the Canada’s prime minister to exercise his fiduciary duty to protect Aboriginal and treaty rights from provincial assault. To his great discredit, Trudeau failed to do so before going public with his deal.

This betrayal of his responsibilities was hardly an isolated case. One of Trudeau’s worst assaults on Canadian interests was his decision to take away sovereign control over the issuance of near-interest-free money from the Bank of Canada. In 1974 this money power power was handed over to the private central bankers in the Rothschild-dominated Bank of International Settlements in Switzerland.

The exclusion of Aboriginal peoples from representation in the negotiation of the Constitution Act, 1982 is reminiscent of their being excluded from any role whatsoever in the proceedings of the St. Catherine’s Milling case. It seems that bad things happen when Aboriginal people are not present to defend themselves, their lands and their treaties with the Crown in the course of important transactions concerning federal-provincial relations.

Aboriginal peoples and their supporters created sufficient political leverage that section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982 was reinstated with one modification. That slightly revised provision proclaims that “the existing Aboriginal and Treaty of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” The Aboriginal peoples of Canada are defined as “Indians, Inuit and Metis.”

Justin Trudeau Wildly Signals His Virtue as a Wannabe Fixer of the Climate

In his first term as Prime Minister beginning in 2015 Trudeau tried to navigate his way through a wide array of contradictory demands. For instance, Trudeau tried his hand at building pipelines, negotiating treaties with Aboriginal peoples in BC, conserving the majesty of some of BC’s wild places, helping to facilitate overall economic prosperity, and contending with the extremism of some climate-change zealots.

If Trudeau had been invested with a decent skill set, a comprehending mind, and reasonable awareness of history, he would have been able to soldier on. He would have been able to bring about viable compromises, necessary trade offs, and political accommodations to safeguard the rights as well as to advance the interests of all the Canadian people.

This kind of outcome, however, cannot be expected of leaders who attack their own citizens to advance the globalist agendas of the Davos billionaires’ club. This kind of outcome is certainly not consistent with the limited capacity and attention span of Justin Trudeau, a perpetual adolescent who is well known as a stoner video game addict.

As the extent of Trudeau’s failures and scandals mounted, he was drawn to follow the line of least resistance. Especially after participating in the Glasgow Climate Pact in 2021, Prime Minister upped his infatuation with carbon taxes and pictured himself as the superman of anti-climate change.

In adopting the religion of climate change fanaticism, Trudeau radically turned against the Canadian oil and gas industry centred in Alberta where the Prime Minister has many enemies and few political allies. See this.

After Trudeau failed in 2021 for the second time to achieve a majority government in Parliament, he went for broke by appointing Greenpeace activist Steven Guilbeault as his Minister of Environment and Climate Change. Dubbed by La Presse as “the Green Jesus of Montreal,” Guillbeault made a name for himself in 2001 by climbing Toronto’s CN Tower to protest Canada’s poor environmental record. See this.

Once he took office, Guilbeault began slapping increasingly harsh and compressed trajectories of caps on carbon emissions, allegedly a basis of so-called greenhouse gases. This attack on Alberta’s oil and gas industry was a major factor that helped him create the conditions that put in place both Premier Danielle Smith and her work-in-progress, the Alberta Sovereignty Act.

Premier Smith views the issuance of emission caps by Ottawa as basically the same thing as putting caps on oil and gas production. Such federal caps on production, Smith argues, amount to a federal intrusion into Alberta’s realm of exclusive provincial sovereignty.

Premier Smith derives her view that the federal government does not have a right to dictate the rate of the production of oil and gas, from the 1982 amendments in the Constitution Act, 1867. The relevant provision states,

92A (1) In each province, the legislature may exclusively make laws in relation to

(b) development, conservation and management of non-renewable natural resources and forestry resources in the province, including laws in relation to the rate of primary production therefrom; and

Premier Smith has alleged that if Ottawa persists in forcing its agenda on Alberta, the result will be the fairly quick elimination of about half of Alberta’s oil and gas production. Cutting half the production would result in the loss of about half of the well-paying Oil Patch jobs that have long employed hard-working men and women from all across Canada.

A citizen of Quebec, Guilbeault is helping to spark the widespread resentment of Albertans. Many Albertans are well aware that much of the wealth generated by Alberta’s Oil Patch ends up in equalization transfer payments that go in significant measure to the government of Quebec.

Quebec has significant oil and gas resources of its own. Those controlling Quebec’s government, however, do not want to develop these resources because it would halt the transfer payments from Alberta. This decision deprives many Quebecers of employment that would raise their standard of living. This kind of improvement for Quebec citizens, however, is deemed secondary to feeding off the labour of Albertans.

Smith asserted on 30 August that Guilbeault is showing “utter contempt for Alberta.” See this.

The concerted attack by the government of Canada on the continued development of Canada’s most valuable natural resource flies in the face of common sense. The attack by Ottawa on Alberta in 2023 is even more aggressive than Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Policy of the early 1980s. Moreover the current interventions by Trudeau junior fly in the face of recent international developments the world over.

The news is getting out that there is no viable Plan B to replace any time soon the relatively cheap and efficient industrial muscle of oil and gas. The secret is out that wind power and solar power are both ephemeral as well as costly and environmentally problematic in a multiplicity of ways.

This return to the fundamentals of the oil and gas industry in Alberta and many other jurisdictions, is reflected in the decision of Rich Kruger, the CEO of Suncor, “to refocus on its oil and gas assets.” See this.

Responding from China where Guilbeault [allegedly] seems to be yet another Liberal Party agent working for the Chinese government, the Climate Change Minister lashed out in a very threatening way, aiming especially at Kruger and Suncor. Guilbeault has already put in place the mechanisms to criminalize those that don’t agree to march to Ottawa’s climate-change dictates.

Guilbeault was upset “to see the leader of a great Canadian company say he is basically disengaging from climate change and sustainability… it’s all the wrong answers. If I was convinced before we needed to do regulation, I am even more convinced now.” See this.

The implications of abandoning oil and gas in favour of the ridiculous campaign to stop the climate from changing, are already generating dire consequences. The consequences will include more unemployment, more poverty, more suicide, and more exposure to arbitrary controls like climate-change lockdowns, manufactured famines and social credit penalties. Net zero sums it up well.

Premier Smith is trying to fix the limitations Alberta is facing as a landlocked jurisdiction, with a dearth of pipeline connections providing easy access to ocean transport.

Premier Smith is joining together with the premiers of Saskatchewan and Manitoba as well as an Aboriginal corporation, NeeStanNan, to establish a transportation corridor to a new Deep Sea port. That port is to be at the mouth of the Nelson River flowing into the coastline of southwest Hudson’s Bay. See this.

Transport from Europe into the deep North American interior through Hudson’s Bay has long and venerable place in Canadian history. This transportation route was the key to the success of the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1671 to 1871, when Manitoba and Canada’s North West Territories was created.

The decision of the United States to knock out trade in oil and gas between Russia and Germany as well as the rest of the European Union, has heightened the geopolitical imperative to open up a Deep Sea port on Hudson’s Bay. For the time being, this initiative is being pushed forward primarily from the foundation of provincial and Aboriginal jurisdiction as the federal government continues to signal its virtue as a supposed fixer of the climate.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on the author’s Substack.

Dr. Anthony Hall is editor in chief of the American Herald Tribune. He is currently Professor of Globalization Studies at University of Lethbridge in Alberta Canada. He has been a teacher in the Canadian university system since 1982. Dr. Hall, has recently finished a big two-volume publishing project at McGill-Queen’s University Press entitled “The Bowl with One Spoon”.

He is a regular contributor to Global Research.