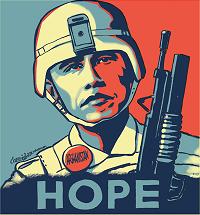

Obama Scraps Iraq Withdrawal

So, we elected a president who promised a withdrawal from Iraq that he, or the generals who tell him what to do, is now further delaying. And, of course, the timetable he’s now delaying was already a far cry from what he had promised as a candidate.

What are we to think? That may be sad news, but what could we have done differently? Surely it would have been worse to elect a president who did not promise to withdraw, right?

But there’s a broader framework for this withdrawal or lack thereof, namely the SOFA (Status of Forces Agreement), the unconstitutional treaty that Bush and Maliki drew up without consulting the U.S. Senate. I was reminded of this on Tuesday when Obama and Karzai talked about a forthcoming document from the two of them and repeatedly expressed their eternal devotion to a long occupation.

The unconstitutional Iraq treaty (UIT) requires complete withdrawal from Iraq by the end of next year, and withdrawal from all Iraqi cities, villages, and localities by last summer. Obama’s latest announcement doesn’t alter the lack of compliance with the latter requirement. Nor does it guarantee noncompliance with the former. But it illustrates something else, something that some of us have been screaming since the UIT was allowed to stand, something that pretty well guarantees that the US occupation of Iraq will never end.

Imagine if Congress funded, defunded, oversaw, and regulated the military and wars as required by our Constitution. Imagine if the president COULDN’T simply tell Congress that troops would be staying in Iraq longer than planned, but had to ask for the necessary funding first. Here’s the lesson for this teachable moment:

Persuading presidents to end wars only looks good until they change their mind. Cutting off the funding actually forces wars to end.

When the US peace movement refused to challenge the UIT, it left Bush’s successor and his successors free to ignore it, revise it, or replace it. Congress has been removed from the equation. If Obama decides to inform Congress that the occupation of Iraq will go on into 2012, Congress’ response will be as muted as when the Director of National Intelligence informed Congress that killing Americans was now legal. And what can Congress say? It had no role in ratifying the UIT in the first place.

And the peace movement is in large part on the same path with Afghanistan, working to pass a toothless, non-binding timetable for possible redeployment of troops to another nation. Congress sees itself as advisors whose role it is to persuade the president that he wants to cease the activity that most advances presidential power. And activists share that perspective.

But what happens if the president becomes unpersuaded about ending both of these wars? What in the world are we supposed to do then?

We have an alternative to painting ourselves into this corner. The alternative is to build a movement of war opponents (and advocates for spending on human needs and/or tax cuts) that can pressure the House of Representatives to cut off the funding for the wars. Of course, this isn’t easy. It’s much harder than collecting signatures on a toothless resolution. And it’s dramatically harder than watching the president create an unconstitutional treaty (something Bush was forced into primarily by the people of Iraq) and then stepping aside to celebrate.

But there is no stronger message that could be used to persuade a president than a growing caucus of congress members denying him the money. And once a majority is reached in the caucus of war defunders, then the war simply has to end, whether the president is persuaded of anything or not.

So, the lesson to be learned from Obama scrapping his current plan for an Iraq withdrawal is not that we should phone the White House and complain. It’s not that we need 20 more cosponsors of the nonbinding timetable for Afghanistan. The lesson is that we must tell members of the House of Representatives that they can vote against war funding or we will vote against them.

Not a new lesson, I realize, but the Constitution is always less read than talked about.