Obama’s Nuclear Postures: The Nuclear Weapons Complex

The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review

In his first official statement after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, President Harry Truman claimed the new weapon as a fundamental breakthrough in military capability and a uniquely American achievement. The Hiroshima bomb, he said, was “more than two thousand times the blast power of…the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare,” drawing its enormous destructive force from “a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.” With the bomb, Truman declared, “We have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces.” It was made possible, he claimed, only because “the United States had available the large number of scientists of distinction in the many needed areas of knowledge. It had the tremendous industrial and financial resources necessary for the project…. It is doubtful if such another combination could be got together in the world.”

It did not take long for Truman to be proven wrong. Nuclear weapon programs soon sprang up in other countries. The Soviet Union tested its first bomb in 1949, Britain in 1952 and France in 1960. When China carried out a nuclear explosion, in 1964, it showed nuclear weapons were an option for states lacking extensive scientific, industrial or financial resources. Weapons also increased quickly in destructive power as the atom bomb gave way to the hydrogen bomb. In 1954, the US tested a hydrogen bomb with a yield about a thousand times larger than the Hiroshima bomb. Seven years later the Soviet Union exploded a bomb that was almost four times larger still.

Threat Recognition

Truman’s successors recognized the threats posed by the arms race and nuclear proliferation. In September 1961, speaking to the UN General Assembly, a very young and charismatic American president, John F. Kennedy, warned, “Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness. The weapons of war must be abolished before they abolish us.” Kennedy proposed that to end the nuclear danger, “disarmament negotiations resume promptly, and continue without interruption until an entire program for general and complete disarmament has not only been agreed but has actually been achieved.” This program, he argued, should involve “a steady reduction in force, both nuclear and conventional, until it has abolished all armies and all weapons except those needed for internal order and a new United Nations Peace Force.”

Instead of disarmament, Kennedy presided over the Cuban missile crisis and a marked increase in the US nuclear arsenal (from about 20,000 warheads in 1960 to almost 30,000 warheads in 1963). In parallel, there was a massive conventional military buildup and the start of the war in Vietnam. The nuclear arsenal was recognized at the time as being far larger than any conceivable military utility. In 1964 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara proposed the arsenal be sized so as to achieve the “assured destruction” of the Soviet Union and argued that “the destruction of, say, 25 percent of its population (55 million people) and more than two thirds of industrial capacity would mean the destruction of the Soviet Union as a national society.”[1]

McNamara estimated that it would require about 400 nuclear weapons of the kind the US then had in its arsenal to wreak this level of devastation. He pointed out that “the proportion of the total population destroyed would be increased by only about ten percentage points” if the US were to use 800 nuclear weapons. Despite McNamara’s analysis, the number of US warheads peaked at just over 31,000, in 1967, a year before McNamara stepped down. In 2010, over 40 years since McNamara’s assessment and 20 years after the Soviet Union collapsed, the US maintains a declared stockpile of 5,113 nuclear weapons, of which about 2,700 are operational warheads, with another 2,500 in reserve. There are a further 4,200 warheads in the queue to be dismantled.

Kennedy was also the first president to warn in stark terms of the danger of the spread of nuclear weapons. In an address to the nation in 1963, Kennedy described his fears:

During the next several years, in addition to the four current nuclear powers, a small but significant number of nations will have the intellectual, physical and financial resources to produce both nuclear weapons and the means of delivering them. In time, it is estimated, many other nations will have either this capacity or other ways of obtaining nuclear warheads, even as missiles can be commercially purchased today.

I ask you to stop and think for a moment what it would mean to have nuclear weapons in so many hands, in the hands of countries large and small, stable and unstable, responsible and irresponsible, scattered throughout the world. There would be no rest for anyone then, no stability, no real security, and no chance of effective disarmament. There would only be the increased chance of accidental war, and an increased necessity for the great powers to involve themselves in what otherwise would be local conflicts.

Classified US intelligence estimates at the time warned of countries that might follow down the nuclear road, including Israel, India and Pakistan — the three that did so.[2]

Fearing the further spread of nuclear weapons, in 1968 the US and Soviet Union agreed on a nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and presented it to the world. It came into force in 1970. The treaty obliged nuclear weapon state signatories (defined as those what had carried out a nuclear test before January 1967) to eliminate their weapons in exchange for non-weapon countries never building them. To ensure that nuclear energy programs in non-weapon states were not used covertly to make weapons, nuclear facilities were to be monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). At the time, the US, Soviet Union, Britain, France, China and Israel all had nuclear weapons, but Israel had not carried out a test. Since then, four more countries have acquired nuclear weapons — India, Pakistan, South Africa and North Korea. South Africa gave up its weapons and signed the NPT. North Korea signed the NPT, made nuclear weapons and left the treaty.

The NPT is 40 years old and there are many who see the treaty as being in grave crisis. The nuclear-armed states have not delivered on nuclear disarmament; there have as yet been no talks on how they would make good on this commitment. Some countries that signed the treaty as non-weapon states tried secretly to make nuclear weapons. There is growing concern about Iran’s intentions. Many now also fear that, having spread from rich, industrialized states to poor, developing ones, nuclear weapons may be within reach of militant groups such as al-Qaeda. Even old Cold Warriors have started to talk of the need to abolish nuclear weapons.

In January 2007, former Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and George Shultz, ex-Secretary of Defense William Perry and Sam Nunn, the former chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, argued that nuclear weapons were perhaps the greatest threat to America today. Echoing Kennedy, they claimed that “unless urgent new actions are taken, the US soon will be compelled to enter a new nuclear era that will be more precarious, psychologically disorienting, and economically even more costly than was [the] Cold War.”[3] They urged the US to embrace the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons. Their vision was endorsed in 2008 by a host of former US secretaries of state and defense and other former senior officials, both Republican and Democrat, including Madeleine Albright, James Baker, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Warren Christopher, Colin Powell and Robert McNamara.

This realization has been a long time coming. In the shadow of the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the UN in its very first resolution called for plans “for the elimination from national armaments of atomic weapons and of all other major weapons adaptable to mass destruction.” For over 60 years civil society groups around the world have struggled to abolish nuclear weapons in what was perhaps the first truly global social movement. The hibakusha, the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have borne witness to the horrors of nuclear weapons. Scientists and physicians have warned of the dangers of arms races and nuclear war. Artists, writers, filmmakers and poets gave expression to collective fears and hopes. Countless citizens petitioned leaders, marched and protested. The story of this movement is being recovered by the historian Lawrence Wittner.

Public support for nuclear abolition is evident in polls showing overwhelming majorities even in the nuclear weapon states in favor of a verified agreement to eliminate nuclear weapons. A poll carried out in 21 countries by the Global Zero campaign covering all the countries with nuclear weapons, except for North Korea, found that, on average, across all these countries, three out of four people support an international agreement for eliminating all nuclear weapons according to a timetable.

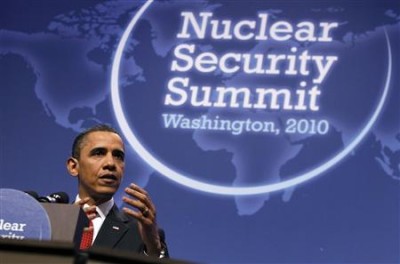

The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review

The election of President Barack Obama raised hopes that the long sought-after goal of abolishing nuclear weapons might finally become a US aim. In April 2009 in Prague, in what has become an iconic speech, Obama said: “As the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act…. So today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons.” The reason Obama gave, echoing Kennedy 50 years earlier, was that the nuclear danger was increasing uncontrollably:

Today, the Cold War has disappeared but thousands of those weapons have not. In a strange turn of history, the threat of global nuclear war has gone down, but the risk of a nuclear attack has gone up. More nations have acquired these weapons. Testing has continued. Black market trade in nuclear secrets and nuclear materials abound. The technology to build a bomb has spread. Terrorists are determined to buy, build or steal one. Our efforts to contain these dangers are centered on a global non-proliferation regime, but as more people and nations break the rules, we could reach the point where the center cannot hold.

Six months later, Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Prize Committee said that in making the award it “attached special importance to Obama’s vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.”

The first evidence for how the Obama Administration plans to address the goal of nuclear disarmament came in April 2010, with the publication of the Nuclear Posture Review Report. The report is required by Congress and is meant to establish US nuclear policy, strategy and capabilities. The Obama review was the third such exercise: The first occurred under President Bill Clinton in 1994 and the second under President George W. Bush in 2002. Only Obama’s was published in full; the earlier reports were summarized and excerpted. A comparison of the Obama report with the excerpts from the one prepared by the Bush administration reveals fundamental continuity in US nuclear policy rather than the kind of sweeping changes that would be required to move toward eliminating nuclear weapons.

Nuclear Weapons and Strategic Stability

In 2002, the Bush Posture Review Report read, “Nuclear weapons play a critical role in the defense capabilities of the United States, its allies and friends.” But the review recognized that nuclear weapons are of limited utility, arguing, “US nuclear forces, alone, are unsuited to most of the contingencies for which the United States prepares.”

The 2010 Obama review echoes this judgment, observing that nuclear forces “play an essential role in deterring potential adversaries and reassuring allies and partners around the world,” but admitting that warheads are “poorly suited to address the challenges the US now faces.” While “allies” are mentioned in both the Bush and Obama formulations, presumably in reference to members of the NATO alliance, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, it is harder to guess which countries were described in 2002 as “friends” and in 2010 were relabeled as “partners.”

This deliberate ambiguity allows the US great freedom to pick and choose when and where it will unfurl its nuclear umbrella. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has suggested, for example, that if Iran proceeds to acquire nuclear weapon capabilities, the US may use nuclear weapons to defend its “partners” in the Gulf.

The Bush Posture Review proposed that US nuclear weapons should be seen as an integral part of a larger set of established and emerging strategic capabilities that are “required for the diverse set of potential adversaries and unexpected threats the United States may confront in the coming decades.” It proposed developing new conventional weapons able to attack a target anywhere in the world, deploying ballistic missile defenses, maintaining the triad of nuclear delivery systems (submarine-launched missiles, land-based missiles and bombers), extending the lifetime of existing nuclear warheads and modernizing the nuclear weapons research and development complex. The Obama Posture Review accepted this way of looking at nuclear weapons and adopted all of these policy goals.

The Obama review committed in particular to what has come to be known as Prompt Global Strike, which refers to the use of conventional warheads on intercontinental ballistic missiles able to reach any location in the world in less than 30 minutes. The review claims this capability is “particularly valuable for the defeat of time-urgent regional threats.” According to Gen. Kevin Chilton, head of US Strategic Command, he can now only present “some conventional options to the president to strike a target anywhere on the globe that range from 96 hours, to several hours maybe, four, five, six hours.”[4] Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, who served Obama’s predecessor, has observed that Prompt Global Strike “really hadn’t gone anywhere in the Bush administration,” but was being “embraced by the new administration.”

Missile defense, another of Bush’s favorites, is featured prominently in the Nuclear Posture Review Report from 2010. In 2002, it was argued that “the mission for missile defense is to protect all 50 states, our deployed forces, and our friends and allies against ballistic missile attacks.” In the 2010 report, the goal is to “respond to regional threats by deploying effective missile defenses, including in Europe, Northeast Asia, the Middle East and Southwest Asia.”

While claiming that Prompt Global Strike and missile defenses are intended for “regional threats,” the 2010 report recognizes that Russia and China “are claiming US missile defense and conventionally armed missile programs are destabilizing.” In short, Russia and China see Prompt Global Strike and missile defense capabilities as threatening the strategic balance these countries feel they currently have with the US. Rather than abandon these weapon systems, the posture review proposes high-level, bilateral dialogues on “strategic stability” with Russia and China.

A goal of maintaining strategic stability with Russia and China would suggest that the US has recognized a mutual deterrence relationship with both countries, even though they have very different nuclear arsenals. Russia (like the US) has some 5,000 operational nuclear weapons. China is estimated to have less than 250 warheads, of which only 20 are believed to be on long-range ballistic missiles able to reach the North American continent. The Posture Review Report does not explain why the US could not reduce its arsenal to the same level as China, and ask Russia to do the same. The April 2010 US-Russia New-START agreement limits the two countries to 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads each, with the target to be reached by seven years after the treaty enters into force. The treaty is awaiting ratification in both countries.

The Nuclear Weapons Complex

The 2002 posture review focused considerable attention on the need to sustain and modernize the US nuclear weapons research design and production complex. It pointed to “underinvestment in the infrastructure — in particular the production complex,” and proposed establishing a new capacity to produce nuclear weapon components. Modern US nuclear weapons are two-stage thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs). These comprise a fission primary (in essence a small atomic bomb) based on a plutonium core, or pit, which explodes and ignites the thermonuclear fuel in a secondary made of highly enriched uranium. Facilities for producing these components were to be set up at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico and the Y-12 complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. All this despite the fact that the US already has in its weapons and in storage thousands of plutonium pits that have projected lifetimes of at least 100 years and uranium secondaries that may last even longer.

The 2010 report makes the same argument, claiming: “In order to sustain a safe, secure and effective US nuclear stockpile as long as nuclear weapons exist, the United States must possess a modern physical infrastructure — comprised of the national security laboratories and a complex of supporting facilities — and a highly capable work force with the specialized skills needed to sustain the nuclear deterrent.” It commits to funding the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Project at Los Alamos and a Uranium Processing Facility at the Y-12 Plant, which would produce, respectively, the plutonium and uranium components for nuclear weapons. The combined cost is expected to be on the order of $6-7 billion.

In line with its posture review, the Obama White House intends to spend $80 billion over the next decade on nuclear weapon complex modernization. Linton Brooks, who served as head of the National Nuclear Security Administration and managed the nuclear weapons complex in the Bush administration, said at an April 7 Arms Control Association briefing in Washington, “I ran that place for five years and I’d have killed for that budget.”

For the next fiscal year, the Obama administration has proposed one of the largest increases in nuclear warhead spending in US history. Los Alamos National Laboratory will see a 22 percent increase in its budget, said to be the largest one-year jump since 1944. The flagship project is the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Nuclear Facility, which could produce 125 plutonium pits per year and as many as 200 pits year.[5] This annual production capacity is roughly equivalent to the total arsenal of Britain (less than 200 weapons) or a large fraction of the arsenals of China (250 weapons) or France (less than 300 weapons).

The Obama administration has proposed additional spending of “well over $100 billion” on nuclear weapon delivery systems, including new land-based missiles, new submarine-launched missiles, new submarines and bombers.[6]

Using Nuclear Weapons

A critical element of nuclear policy is elaboration of the conditions under which the US might use nuclear weapons, as well as when the US might refrain from their use. In February 2002, the Bush administration reaffirmed the policy adopted by the Clinton administration that the US “will not use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states parties to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, except in the case of an invasion or any other attack on the United States, its territories, its armed forces or other troops, its allies or on a state toward which it has a security commitment, carried out or sustained by such a non-nuclear weapon state in association or alliance with a nuclear weapon state.”

The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review also addressed this issue, and after considerable debate inside the administration, resolved that “the United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapons states that are party to the NPT and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

This formulation of what is known as a “negative security assurance” appears to be an advance on the previous policy, but is less straightforward than it appears. It does not, for instance, make clear what specific non-proliferation obligations a non-weapon state would have to comply with to be assured of being free from US nuclear threats. Nor does it specify who would decide about compliance. Currently, possible NPT violations are determined by the IAEA’s Board of Governors, which is required to report violations to the UN Security Council.

Asked to clarify this position at a Carnegie Endowment event in April, the White House’s coordinator for arms control and weapons of mass destruction, proliferation and terrorism, Gary Samore, explained that “incompliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations is intended to be a broad clause and we’ll interpret that — when the time comes, we’ll interpret that in accordance with what we judge to be a meaningful standard.” On the question of who would determine if a country is non-compliant, Samore argued, “That’s a US national determination. I mean, obviously, we’ll be influenced by the actions of other parties. If the IAEA Board of Governors decides that a country is not in compliance with their safeguards obligation, it would be difficult or — not impossible, but difficult — for the US government to ignore that.”

This interpretation suggests that the US intends to be the sole judge of what non-proliferation obligations a non-weapon state must uphold to be safe from the threat of nuclear attack; whether a state is violating these obligations; and, in making this judgment, the US reserves the right to override the relevant international law and international institutions. Given the ongoing disputes among Security Council members about the extent and seriousness of Iranian non-compliance with NPT obligations, the Obama White House’s interpretation of these phrases should be a matter of great concern.

Toward a World Without Nuclear Weapons

In his 2009 Prague speech, President Obama explained that while he wanted “the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” he recognized that “this goal will not be reached quickly — perhaps not in my lifetime.” Six months later, the goal seemed to recede even further in to the future. In a Washington speech, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton argued, “We might not achieve the ambition of a world without nuclear weapons in our lifetime or successive lifetimes.” She did not say how many lifetimes it could take. In the meantime, she told an ABC interviewer, “We’ll be, you know, stronger than anybody in the world, as we always have been, with more nuclear weapons than are needed many times over.”

The Obama Nuclear Posture Review Report, while embracing the goal of abolition, reveals why it is believed the path to a nuclear weapons-free world will be interminably slow and have many pitfalls. The report specifies that some of the preconditions for eliminating nuclear weapons are:

success in halting the proliferation of nuclear weapons, much greater transparency in the programs and capabilities of key countries of concern, verification methods and technologies capable of detecting violations of disarmament obligations, enforcement measures strong and credible enough to deter such violations, and ultimately the resolution of regional disputes that can motivate rival states to acquire and maintain nuclear weapons. Clearly, such conditions do not exist today.

The final precondition stipulates in effect that world peace must be achieved before the US and its strategic allies and partners will contemplate abolishing nuclear arsenals. Such a stipulation would stand on its head the premise of the NPT, as well as the speeches of Presidents Kennedy and Obama, that the existence of nuclear weapons is itself the salient threat to global peace and security.

The majority of states do not share the Obama administration’s way of thinking about how to proceed. Interest is gathering in negotiating a nuclear weapons convention, modeled on the treaties that banned chemical and biological weapons. Each year, large majorities at the UN General Assembly carry resolutions recognizing that “there now exist conditions for the establishment of a world free of nuclear weapons” and calling for the start of negotiations on the total elimination of nuclear weapons. The momentum was evident most recently in the May 2010 final declaration of the NPT review conference, which said, “All States need to make special efforts to establish the necessary framework to achieve and maintain a world without nuclear weapons.” The declaration called, in particular, for “consideration of negotiations on a nuclear weapons convention or agreement on a framework of separate mutually reinforcing instruments, backed by a strong system of verification.”

The elimination of nuclear weapons is being discussed today with a seriousness that has been absent during most of the nuclear age. The goal commands widespread support among states and peoples. Rhetoric aside, the US under President Barack Obama remains committed to a familiar nuclear posture based on retaining nuclear weapons for the indefinite future and accepting scant constraint on how these weapons might be used.

Zia Mian is a physicist with the Program on Science and Global Security at Princeton University and an editor of Middle East Report.

Notes

[1] Robert McNamara to Lyndon B. Johnson, “Recommended FY 1966-1970 Programs for Strategic Offensive Forces, Continental Air and Missile Defense Forces, and Civil Defense,” December 3, 1964, National Security Archive, accessible at: www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nukevault/ebb311/doc02.pdf.

[2] “National Intelligence Estimates of the Nuclear Proliferation Problem: The First Ten Years, 1957-1967,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book 155, June 1, 2005, accessible at: www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB155/index.htm.

[3] Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, William Perry and Sam Nunn, “A World Free of Nuclear Weapons,” Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2007.

[4] New York Times, April 22, 2010.

[5] For details on the CMRR project, see www.lasg.org/CMRR/open_page.htm.

[6] Washington Post, May 14, 2010.