Nukes on the Screen. Seventy Years of Atomic Danger

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

Numerous films, some of them based on novels, feature nuclear war, its potential impacts, and the extreme threat these weapons pose. One of the first was Godzilla, a 1954 Japanese production re-released in the US two years later with Raymond Burr in a key role. The title monster is widely considered an analogy to the nuclear weapons dropped on Japan. But films about the danger of nuclear weapons actually began to appear years before with a fictionalized docudrama. The Beginning of the End (1947) focused on the Manhattan Project and nuclear bombing of Hiroshima — which had happened only two years earlier.

The mutant monster genre’s beginnings coincided with the McCarthy era, a time when paranoia wasn’t an unreasonable response to what was happening. Nuclear-spawned giant Ants prowled the Los Angeles sewers in Them, while The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, with special effects by Ray Harryhausen, revolved around a dinosaur thawed from frozen hibernation by a atomic test in the Arctic Circle.

The most effective film of that genre’s early years may have been The Incredible Shrinking Man, based on a novel and featuring groundbreaking effects. The 1957 movie opens with the irradiation of Scott, an average guy vacationing with his wife when a strange mist covers him. This sets off his gradual descent into a very different and threatening world. Scott does ultimately experience an existential liberation at sub-atomic size. But the Japanese fisherman whose irradiation by a bomb test inspired the story wasn’t as lucky.

The treatment of nuclear weapon detonation turned more serious as the decade ended with On the Beach. Based on a popular 1957 novel, the film, released in 1959, was an effective melodrama with A-list stars that followed the travails of nuclear war survivors in Australia as they confront death and the end of humanity.

In the 1960s, films began to seriously address how a nuclear conflict could start and how people might react. In Panic in the Year Zero (1961), starring Ray Milland, a family on a camping trip flees a nearby nuclear attack, encountering looters and other violent people as society breaks down. Released the same year, The Day the Earth Caught Fire suggests that nuclear tests could throw the Earth off course. The planet is doomed unless scientists figure out how to reverse the change. Spoiler: the outcome isn’t clear. The final sequence shows two newspaper front pages. One declares “World Saved,” the other “World Doomed.”

Two of the most enduring films about the possibility of ending up in a nuclear war by accident were released in 1964. Both were based on novels. Fail-Safe takes an intellectual approach, chronicling how politicians, scientists and the military handle the accidental bombing of Moscow when command and control systems fail. To save the rest of the world, the US president, sympathetically portrayed by Henry Fonda, decides to balance the scale of tragedy by nuking New York.

Dr. Strangelove (or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb), directed by Stanley Kubrick, opted for black comedy. Based loosely on Red Alert, a 1958 novel, it features the idea that a hypothetical Doomsday Machine would be beyond human control. It also suggests that sexual and mental problems could put the fate of humanity in the hands of one deranged general.

Around the same time, the James Bond franchise was launched, and subsequently used the threat posed by nuclear weapons falling into the “wrong” hands as the super-spy’s motivation in ten films over three decades. Some focus on theft or threatened use by criminal groups, others on a showdown between the superpowers. Bond always saves the planet, of course. But Polaris missiles are used to destroy a stolen nuclear sub in The Spy Who Loved Me. Defying both science and reason, only the bad guys are killed.

In Goldfinger (1964), the gold-obsessed villain plots the collapse of the West’s economy to enrich himself, with Chinese and North Korean accomplices, by irradiating the gold reserve at Fort Knox. In Octopussy (1977), another installment with convenient Cold War villains, a renegade Soviet general joins forces with Afghan and Indian smugglers to derail disarmament talks and invade Western Europe by detonating a nuke at a US base in Germany. In Goldeneye (1995), the threat is a hypothetical nuclear satellite weapon that can disable electronics with an EMP attack.

Other Bond films with plots involving nuclear weapons include Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967), Diamonds Are Forever (1971), The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) and The World is Not Enough (1999). By this time, using nuclear weapons as a plot device had become so common that Mike Myers’ spy spoof Austin Powers turned it into a punchline. Assessing various criminal options, Bond-like villain Dr. Evil eventually settles on the obvious. “Let’s just do what we always do,” he proposes, “steal a nuclear bomb and hold the world to ransom.”

Fact-based accounts have been more rare. But the Manhattan Project was soberly dramatized in Fat Man and Little Boy and Day One, both released in 1989, while The Missiles of October (1974) and Thirteen Days (2000) explore the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. In 1983, The Day After, made for television, sparked a national debate by realistically showing the effects of nuclear weapons. It depicts both how a war could happen and the potentially devastating aftermath.

Nuclear films by the decade

The 1950s also included Split Second (1953), in which an escaped killer and his partners hold people hostage in a ghost town slated to be destroyed by a nuclear bomb; and The Atomic Kid (1954), focusing on a man in the danger zone of a nuclear test when the bomb is activated.

Beyond Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe, the 1960s featured Ladybug, Ladybug (1963), also set during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis; A Carol for Another Christmas (1964), in which the Ghost of Christmas Future provides a tour of the ruins of a once-great civilization that looks like Hiroshima; and The Bedford Incident (1965), based on a 1961 novel, depicting a stand off in the North Atlantic between a destroyer and a Soviet submarine caught violating Greenland’s territorial waters. The novel ends with the destroyer accidentally firing a missile at the submarine, and the Soviet submarine responding with four nuclear torpedoes. In the film, the final image is a mushroom cloud.

The War Game (1965), a BBC release, was a mockumentary about the effects of nuclear war on England after a conventional war escalates. And let’s not forget the Planet of the Apes franchise, which also launched in the 1960s. It is set in a future ruled by apes, who take over after a nuclear war destroys mankind. Beginning as a novel, the original film spawned four sequels, and more recent remakes that shift the cause of the ape takeover to biotechnology.

Battle Beneath the Earth (1967) posits a discovery that Communist China, using futuristic vehicles, has tunneled under the US to place nuclear bombs in strategic locations, resulting in a struggle to foil the plan. In the black humor category there is The Bed Sitting Room (1969), an absurdist, post-apocalyptic, satire set in the ruins of London and featuring John Lennon.

The 1970s started slowly, but eventually produced some memorable additions. Two were released in 1977. Damnation Alley, adapted from a Roger Zelazny short story, features a chilling launch and destruction sequence. After the surprise attack, it follows the efforts of some California survivors to reach another group in New York. And Twilight’s Last Gleaming follows a renegade Air Force general who escapes from a military prison and takes over an ICBM silo near Montana. Once there he threatens to launch missiles and jump-start World War III unless the president reveals a secret document about the Vietnam War.

Two years later The China Syndrome had a significant real world impact. A gripping drama about the dangers of nuclear power, it’s effect was intensifed by a real-life nuclear accident at the Three Mile Island plant only weeks after the film opened. Jane Fonda plays a TV reporter who personally witnesses the risk of a meltdown (known as the “China syndrome”) at a local nuclear plant. Tragedy is averted by a quick-thinking but troubled engineer. The film suggests that corporate greed and cost-cutting have led to potentially deadly faults in the plant’s construction. Less serious but equally popular, the Mad Max franchise also began in 1979, leading to four more film in which a heavily-armed loner patrols a bleak post-nuclear wasteland.

The 1980s could be called the golden age of nuclear movies, marked by dozens of popular productions. The decade began with two memorable 1982 films. The Children’s Story, based on a 1960 short story by James Clavell and originally aired on TV, is a short film depicting the indoctrination of an elementary school classroom by a new teacher when a totalitarian government takes over the country. Another is The Atomic Cafe, which effectively explores 1940s and 1950s government propaganda films that were supposed to reassure audiences that nuclear weapons weren’t a threat to their safety.

The next year was even bigger. Special Bulletin was a made-for-TV movie about anti-nuclear activists who detonate a home-made nuke in South Carolina. It’s shot in a live breaking news style. War Games featured a young computer hacker who nearly starts World War III when he inadvertently breaks into a fictional NORAD supercomputer to play the latest video games. In The Dead Zone a teacher, played by Christopher Walken, acquires psychic powers, then learns that a political candidate, portrayed by pre-West Wing Martin Sheen, will order a nuclear strike at some point in the future. Testament, from PBS, depicts the after-effects of a nuclear war in a town near San Francisco. Silkwood, inspired by the true story of Karen Silkwood, who died in a suspicious car accident, dramatizes her struggle to investigate wrongdoing at the Kerr-McGee plutonium plant where she worked. And Barefoot Gen is an anime film depicting the terror of the Hiroshima bombing and its aftermath from the perspective of a child.

Nuclear paranoia went big time in 1984 with the start of The Terminator franchise, featuring a post-apocalyptic future in which artificial intelligence becomes self-aware, identifies humans as a threat, and uses the world’s nuclear arsenal to destroy mankind. All of James Cameron films from 1986 to 1994 featured nuclear explosions. Just as paranoid but more right-wing, Red Dawn revolves around an invasion and occupation of the US by Soviet, Nicaraguan and Cuban forces after a surprise limited nuclear strike.

The docudrama Countdown to Looking Glass dramatizes an international incident, the breakdown of diplomacy, and the escalation of international tensions leading up to a nuclear crisis. One Night Stand, an Australian film, focuses on four teenagers in the Sydney Opera House when news breaks of a US-Soviet conflict in Europe that goes nuclear — first in Europe, and soon in Australia. And Threads, a 1984-85 BBC production based on a British government exercise, shows the effects of an all-out nuclear war on the town of Sheffield.

In 1986, Manhattan Project wasn’t actually about the bomb’s invention, but instead about how, using stolen plutonium, a high school student builds an atomic bomb for a science class project. Two other significant productions that year were When the Wind Blows, an animated film about an elderly British couple in a post-nuclear war world, and The Sacrifice, a philosophical Swedish drama about nuclear war.

In 1987, The Fourth Protocol, Frederick Forsythe’s 1984 novel, was adapted for film. It follows a plot by extreme Soviet elements to encourage unilateral British disarmament. Meanwhile, they smuggle the components of a tactical nuclear bomb into the country for eventual detonation near a US nuclear base the week before an election. Other 1987 releases include Project X, dealing with the testing of lethal exposures to nuclear radiation on how specially-trained chimpanzees perform in computerized flight simulators — based on a real Air Force biomedical research program; Amazing Grace and Chuck, in which a 12-year-old boy becomes anxious after seeing a Minuteman missile on a school field trip and protests by refusing to play baseball; and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, in which the Man of Steel rounds up all the nuclear weapons and hurls them into the Sun, resulting in unintended consequences.

As the decade ended, Miracle Mile (1988) followed a musician who visits the famous Los Angeles shopping zone, gets a wrong number phone call, and overhears a conversation about an imminent nuclear attack. Struggling against fear, denial and panic, he scrambles to save himself and a woman he just met.

Despite the collapse of the Soviet Union, By Dawn’s Early Light (1990) dramatized an accidental limited nuclear exchange between the two Superpowers after a “false-flag” attack on Soviet territory. Rogue Soviet military officials frame NATO in order to spark a full-blown nuclear war. Based on Tom Clancy’s 1984 bestseller, The Hunt for Red October was released the same year, and involves a Soviet naval captain who wants to defect with his crew and his country’s most advanced nuclear missile submarine.

A few years later Matinee, which is mainly a comedy, revisits the Cuban missile crisis, showing the fears of Americans who think they are about to meet their doom. As the Cold War faded, films like Crimson Tide (1995) and Broken Arrow (1996) turned back to the threats posed by human error and private greed. In the former, the problem is mutiny on a nuclear sub; in the latter, it’s the theft of two thermonuclear weapons by a rogue bomber pilot. The Peacemaker (1997) combines emerging concerns about rogue Russian officers with access to nukes and Eastern European terrorists who want the US to suffer as they have. In Deterrence (1999) the possibility of dropping of a nuclear bomb on Baghdad is dramatized.

In the last 20 years, the threats dramatized on film have ranged from terrorists to tornados. In The Sum of All Fears (2002), also based on a Tom Clancy novel, neo-Nazis attempt to spark a nuclear war between the US and Russia by detonating a nuke during a baseball game attended by the president. In Dirty War (2004) radioactive material is smuggled into England, turned into several dirty bombs, and detonated in London. Dirty bombs are also detonated in Right at Your Door (2007), a thriller set in Los Angeles after their use. On the other hand, it’s just a close call in Atomic Twister (2002) when a automated nuclear power plant is in the path of a tornado.

A few recent films have revisited actual events. K-19: The Widowmaker (2002) covers the actual Soviet submarine nuclear accident, and Chernobyl (2019), an HBO mini-series, details the 1986 disaster. Others opt to speculate. In The Divide (2011), survivors of a nuclear attack struggle to survive in the basement of their apartment building as fears and dwindling supplies undermine their behavior and relationships. In Outside the Wire (2021), a near future story, a drone pilot sent into a war zone must work with an android officer to stop a nuclear attack.

Nuclear weapons even play a role in modern superhero sagas. All of Gotham City is held hostage in The Dark Knight Rises (2012), part of the recent Batman series, when mercenaries take control of an armed neutron bomb. And in Watchmen (2009), based on a DC comic book, a super-powered Dr. Manhattan acts as America’s nuclear deterrent in an alternative 1985, while a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan takes the world to the brink of nuclear conflict.

Some things never change.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

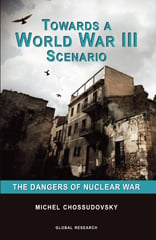

“Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War”

“Towards a World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War”

by Michel Chossudovsky

Available to order from Global Research!

ISBN Number: 978-0-9737147-5-3

Year: 2012

Pages: 102

Print Edition: $10.25 (+ shipping and handling)

PDF Edition: $6.50 (sent directly to your email account!)

Michel Chossudovsky is Professor of Economics at the University of Ottawa and Director of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG), which hosts the critically acclaimed website www.globalresearch.ca . He is a contributor to the Encyclopedia Britannica. His writings have been translated into more than 20 languages.

Reviews

“This book is a ‘must’ resource – a richly documented and systematic diagnosis of the supremely pathological geo-strategic planning of US wars since ‘9-11’ against non-nuclear countries to seize their oil fields and resources under cover of ‘freedom and democracy’.”

–John McMurtry, Professor of Philosophy, Guelph University

“In a world where engineered, pre-emptive, or more fashionably “humanitarian” wars of aggression have become the norm, this challenging book may be our final wake-up call.”

-Denis Halliday, Former Assistant Secretary General of the United Nations

Michel Chossudovsky exposes the insanity of our privatized war machine. Iran is being targeted with nuclear weapons as part of a war agenda built on distortions and lies for the purpose of private profit. The real aims are oil, financial hegemony and global control. The price could be nuclear holocaust. When weapons become the hottest export of the world’s only superpower, and diplomats work as salesmen for the defense industry, the whole world is recklessly endangered. If we must have a military, it belongs entirely in the public sector. No one should profit from mass death and destruction.

–Ellen Brown, author of ‘Web of Debt’ and president of the Public Banking Institute