Nicaragua’s Indigenous People: Neocolonial Lies, Autonomous Reality

All Global Research articles can be read in 27 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

***

Between November 11 and 16, 2020, between the passing of Hurricane Eta and the arrival of Hurricane Iota, the Tortilla con Sal media collective visited Nicaragua’s Autonomous Region of the Northern Caribbean Coast. There we interviewed representatives of different indigenous and afro-descendant territorial governments in Siuna, Bilwi, Waspam and community members of the Miskito communities of Wisconsin and Santa Clara. We also spoke with cattle farmers, residents and officials from the municipalities of Siuna and Prinzapolka about various aspects of the area’s social and economic development. The interviews confirm the success of Nicaragua’s indigenous and afro-descendant peoples in their historic struggle to reclaim their ancestral rights.

The conversations also confirm that the indigenous peoples of Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast have achieved progressive restitution of their rights in large part due to the commitment to the reincorporation of the Caribbean Coast by the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) ever since their historic program of 1969. While in government in 1987, the FSLN passed Law 28 “Statute of Autonomy of the Regions of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua”. Later, while in opposition, the FSLN in 2005 managed to secure the passage of Law 445 “Law of Communal Property Regime of the Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Communities of the Autonomous Regions of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua and of the Bocay, Coco, Indio and Maíz Rivers”.

To date on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, 23 original peoples’ territories have been titled and delimited, covering 314 communities with a territorial extension of 37,859.32 km² in which lives a population of more than 200,000 people in more than 35,000 families. The area is equivalent to 31% of the national territory and more than 55% of the territory of Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast. A significant body of laws, administrative norms and declarations attest to the reality of an innovative and ambitious process vindicating the rights of Nicaragua’s indigenous and afro-descendant peoples.

The interviews collected here also explain how these legislative and administrative advances were achieved in various extremely adverse contexts. For example, in 1987 Nicaragua was in the seventh year of a war imposed by the U.S. government in which much of Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast was the scene of constant military conflict.

Then, after 1990, during the period of the Liberal party governments, the process of defending and promoting the rights of Nicaragua’s native peoples was in effect deliberately undermined. So, when Daniel Ortega and the FSLN took office in January 2007, they inherited a process seriously sabotaged and damaged by the neoliberal policies of the previous sixteen years.

The interviews collected here demonstrate, too, the great scope of the process of restitution of the rights of Nicaragua’s original peoples since 2007, in all its social, political, economic and cultural complexity. For example, they clarify that the leaders of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant Territories are people elected by their communities not on the basis of political allegiances but on the basis of community criteria.

Their Territorial Governments and their Community Governments are two of the five levels of government working together in the Autonomous Regions of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. The two levels of government of the indigenous peoples collaborate intimately with the relevant instances of the National Government, with the Regional Governments and with the respective municipal authorities.

This system of government has enabled important changes on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, for example, in terms of electrification and the development of health and water infrastructure and land communications with the Pacific Coast and also in terms of judicial practice, education and health care.

On the Northern Caribbean Coast, the new road to Bilwi, which includes the construction of a 240-meter long bridge over the Wawa River, will shorten the overland travel time to Managua from 24 to 12 hours. In 2021, the entire northern Caribbean coast will be connected to the national electric power system.

A new regional hospital and a new drinking water system are being built in Bilwi. Economic democratization promoted by the central government has promoted new commercial possibilities for the region’s agricultural, fishing and other producers.

In this context of infrastructure modernization and important social and economic advances, the political opposition desperately uses downright falsehoods exploiting the issue of property conflicts in order to attack the Sandinista government led by President Comandante Daniel Ortega.

The big lie promoted by the political opposition in relation to the phenomenon of property conflicts in the territories and communities of the native peoples is that the Sandinista government promotes the invasion by mestizo families of indigenous and afro-descendant lands.

These interviews with indigenous and afro-descendant leaders completely disprove this gross lie. Instead, they explain the historical context in which indigenous leaders associated with the Miskito Yatama political party, have sold lands that were allocated to them under the government of Violeta Chamorro.

Subsequently, during the period in which Yatama and the ruling government Liberal party controlled the regional government and most of the region’s municipal authorities, various corrupt indigenous leaders continued with the illegal sale of indigenous lands to mestizo families. The natural consequence of this process has been that the mestizo families who bought those lands, in turn sold them on to other mestizo families, thus making the problem progressively more complicated and difficult to solve.

The problem of property conflicts only became international news from 2012 onward because in that year the FSLN displaced Yatama in the municipal elections as the region’s main political force and then in 2014 managed to gain control of the regional government.

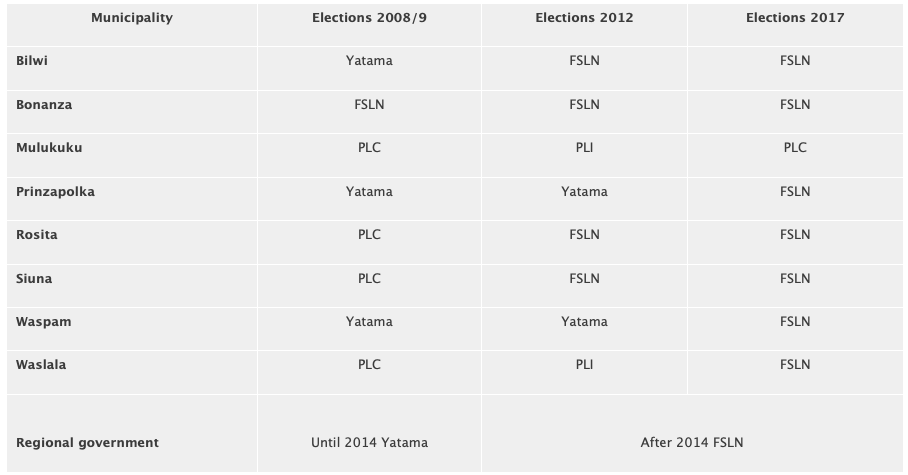

The following table indicates the development of the change of political control in the Northern Caribbean of Nicaragua at the municipal level through the results of municipal elections from 2008 to 2017.

In 2009 Yatama and the Constitutional Liberal Party controlled seven of the eight municipalities in the Northern Caribbean Region. In the 2012 municipal elections Yatama and the Independent Liberal Party won four municipalities between them and the FSLN also four. Then in 2014 Yatama lost the regional elections to the FSLN and in the 2017 municipal elections the FSLN won seven municipalities, leaving only the municipality of Mulukukú in the hands of the PLC. Yatama and the PLC still won a good number of municipal councilors, but without overall control of any municipality.

In response to this decline in the power and influence of Yatama and the Liberal parties in the region, an intense smear campaign has been mounted against the Sandinista government. The campaign is promoted by Yatama and its allies in Nicaragua’s non-governmental organizations associated with the national political opposition, such as the Movimiento Renovador Sandinista, financed from the United States and countries of the European Union.

Similarly, Yatama lost influence at the territorial government level partly because of the deep internal differences within the party and partly because many community members stopped giving the same level of support they had previously given to Yatama’s historic leader Brooklyn Rivera and the indigenous leaders associated with him.

This reality of the unfolding political scene in the Caribbean Coast region of Nicaragua has been systematically suppressed, both by national opposition aligned media and intellectuals and, internationally, by foreign academics and intellectuals allied with Yatama and the MRS. However, the testimony of the indigenous leaders in these interviews convincingly demonstrates the reality, completely disproving the lies that have been spread internationally.

In relation to the issue of bad faith on the part of non-governmental human rights organizations, it may well be worth noting the personal testimony from our visit to interview community members of the Miskito communities of Wisconsin and Santa Clara in the Tasba Raya area, southwest of Waspam. Since 2013, this area has been the scene of some of the most violent incidents of conflict between the indigenous peoples and mestizo settlers.

We arrived in Wisconsin around four o’clock in the afternoon on Saturday, November 14th, 2020. Despite the heavy rains from Hurricane Eta, the road had not deteriorated so badly as to prevent our journey. We went to Wisconsin and Santa Clara because we wanted to talk to people there about their version of local history and events in their community since 2012.

However, the people we were seeking in Wisconsin told us they did not want to be interviewed because they were being watched by community members collaborating with the Center for Justice and Human Rights of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua (CEJUDHCAN) led by Lottie Cunningham Wren. One of the people we wanted to talk to told us, in the presence of three witnesses, they were especially afraid to be interviewed because shortly before our visit, at a community assembly with CEJUDHCAN, Lottie Cunningham Wren had incited hatred against this person, saying that they deserved “to have their throat cut”.

Wisconsin is an impoverished community. However, the people observing our visit had the latest smart phones with which they filmed us. When we asked how it was possible for these very poor people to have such expensive cell phones, we were told that the phones were given out by Lottie Cunningham Wren and her colleagues to CEJUDHCAN collaborators in the community. In any case, we agreed with the community members at that time to record some brief interviews on the subject of local property conflicts and their possible resolution, which we did in a superficially friendly but somewhat tense atmosphere.

Indeed, without the presence of the territorial authorities who accompanied us, we believe it would not have been possible to record interviews in this community. Subsequently, after recording the interviews in Wisconsin, we went to the community of Santa Clara.

There, the community members spoke freely, without fear. They explained what had happened to them in previous years. They spoke of their anxieties and fears regarding the Mestizos and explained their hopes of being able to resolve the problem of property conflicts according to the law.

In both communities, Wisconsin and Santa Clara, the community members insisted that they wanted to avoid the kind of violent incidents of the past and called on the regional and central government authorities to provide the necessary support to expedite the last phase of the titling of their lands, which is called remediation. This term is interpreted in different ways, but the Wisconsin and Santa Clara community members believe that this phase requires clearing a direct lane between the already established trig points in order to clearly define the limits of each territory on the ground.

Taken together, this series of interviews provides an extensive overview of the reality of the Northern Caribbean Coast region based on the concrete experiences of five of the region’s territorial leaders as well as local community members. An undeniable part of that experience has been the incitement to violence by political forces and allied organizations in opposition to the government.

The interviews make clear the mercenary role of foreign funded neocolonial clients like Lottie Cunningham Wren and CEJUDHCAN in that regard. But they also make clear how Liberal party activists and municipal officials have historically promoted the illegal invasion of indigenous lands.

They also highlight the political aspect of organized crime activities in the region, for example the massacre of three police officers in June 2018 near Mulukukú. That massacre occurred in the context of a long-running campaign of systematic harassment in the Mining Triangle of Siuna, Rosita and Bonanza in which dozens of Sandinista militants have been killed in recent years.

It has been a campaign of violence promoted by people associated with the region’s Liberal parties very similar to what has happened in the South Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. There, the activities of the so-called Anti-Canal Movement have been used to cover up organized crime activities aimed at displacing Sandinista families from the area on the municipal border between Nueva Guinea and Bluefields.

The interview series “Nicaragua 2018 – Uncensoring the Truth” extensively details the criminal activities promoted at the time by Anti Canal Movement leaders Francisca Ramirez and Medardo Mairena. Similarly, the interviews compiled here on the reality of Nicaragua’s Northern Caribbean Coast region reveal how opportunist local NGOs such as CEJUDHCAN distort the truth under the guise of promoting the rights of indigenous peoples.

These interviews demonstrate once again that international human rights organizations by no means rigorously and seriously corroborate the denunciations they receive. On the contrary, they act in a morally obtuse, methodologically incompetent and politically biased way, in effect promoting the sinister anti-democratic and anti-humanitarian political agenda of the U.S. government and its allies.

In doing so, they harm and betray the human rights of the very populations they falsely claim they want to defend. Their bad faith has been demonstrated on multiple occasions in the case of Nicaragua, Cuba and Venezuela as well as other countries defending their autonomy and sovereignty against the North American and European imperialist powers.

When former UN Human Rights Rapporteur Alfredo de Zayas said in relation to Venezuela “I realized that the media narrative does not correspond to reality” he could just as well have been talking about Nicaragua. Taken together, the interviews compiled here offer yet more confirmation of the moral bankruptcy of the Western human rights industry and the international media that disseminate their reports with no serious effort to corroborate them, while suppressing other information, such as interviews like these, which contradict them.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Tortilla con Sal.

Featured image is from Tortilla con Sal