Fog Around COVID-19 Made Thicker by New Ontario Rules for Handling Deaths

New Methodology for "Establishing Cause of Death" in Ontario Long-Term Care Homes (LTCHs) and Hospitals. Inflation in COVID Related "Estimates"

Alarming COVID-19 death statistics from seniors’ facilities continue to be in the spotlight in Ontario and elsewhere.

However, all is not as it seems in the mainstream-media reports of those statistics.

Procedures that came into effect in Ontario one month ago for dealing with deaths in long-term-care homes (LTCHs) and hospitals are contributing to exaggeration of the numbers of COVID-19 deaths — and preventing the true causes of many of those deaths from ever being uncovered.

This makes it an opportune time to cast an objective eye on procedures that came into effect in Ontario one month ago for dealing with deaths in long-term-care homes (LTCHs) and hospitals. They differ drastically from both Ontario’s previous regulations and other jurisdictions’ procedures.

In the name of efficiency and safety during the COVID-19 epidemic, the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario (OCC) and members of the province’s funeral-home industry established the new rules and implemented them on April 9. The rules apply to almost every death in the province, not just those attributed to COVID-19.

The new approach is focused on speeding up transfer of the deceased from where they died to a funeral home and then to the place of burial or cremation. The stated goal is to prevent overburdening of medical staff and overfilling of hospital morgues and body-storage areas in long-term-care homes (LTCHs) if there’s a surge in deaths from COVID-19.

However, there are highly problematic parts to this. For example, the new ‘expedited death response’ takes the critical and sensitive task of completing the Medical Certificates of Death (MCODs) out of the hands of the people who know and care for the residents and patients.

Instead, the chief coroner and his staff now have the exclusive right to complete MCODs for people who die in LTCHs. The new rules also give the OCC the power to complete hospital patients’ MCODs. This is despite the members of the OCC very rarely seeing the bodies of LTCH residents and hospital patients, much less meeting them before they die.

“Seeing the body doesn’t actually tell you a lot about the cause of death,” the Chief Coroner for Ontario, Dr. Dirk Huyer, said in an April 20 telephone interview when questioned about this.

Other aspects of the new procedures contribute to the well-documented inflation of the number of COVID-19-linked deaths and they also prevent autopsies from ever being performed on virtually all people designated as having died from COVID-19 (see below).

This author contacted the offices of chief coroners and chief medical examiners for most other Canadian provinces and several American states, and found none have revamped their death-handling processes for LTCH residents or for hospital patients the way Ontario has.

The new Ontario procedures were disseminated April 10 through April 12 via webinars to staff and administrators of LTCHs, hospitals and funeral homes.

According to the OCC’s Q&As for LTCHs and hospitals, the new rules “allow front-line staff to rapidly resume direct patient care.” Also, having the OCC complete the MCODs reduces the number of people who touch the bodies and therefore lowers the potential for virus transmission, the documents assert.

The procedures are based on the supposition that a surge in coronavirus infections and deaths could quickly overwhelm the province’s healthcare capacity.

“We’re really contemplating making sure that we transfer people into funeral-service care by providing some changes that will add – and these words are terrible because this is about people… who have died and families who are suffering … – but it’s [shortening] the timelines, so it’s making things happen quicker. And it’s also increasing efficiencies in the process,” Dr. Huyer said during the April 20 interview.

However, there are no hard data that point to an imminent surge in Ontario. Only the mathematical modelling based on broad assumptions and released on April 3 did so. (Indeed, new modelling released on April 20 showed that cases had peaked.)

The new procedures are not official directives from the chief coroner of Ontario or from the registrar of the Bereavement Authority of Ontario (BAO), which regulates the funeral-home business in Ontario. The OCC website, which is a sub-section of the Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General’s website, has no information about the procedures. Nor do the websites of the Ontario Coroners Association, the Ontario Hospital Association, the Ontario Medical Association, the Ontario Nurses Association or the Ontario Long Term Care Association. The new rules appear to be housed only on the BAO website; they are in website’s coroner’s documents section.

There are many other sweeping changes enshrined in the new rules in addition to the ones outlined above.

For example, those closest to the deceased must contact a funeral home within one hour of the death if it took place in a hospital, and within three hours of a death in an LTCH. No one but staff are allowed to be with the person when they die or touch their bodies in the LTCH or hospital.

The remains then are removed very rapidly. To ensure this happens, funeral homes have quickly hired more staff and now can pick up bodies any time 24/7. Also, staff from the LTCH or hospital put the bodies in body bags and bring them to the waiting funeral-home vehicles. This is the only aspect of the new rules that has received considerable media coverage.

Burial or cremation follows as soon as possible. The BAO reportedly is recommending cremation over embalming.

The new rules also adhere to the World Health Organization’s guidelines. Thus all deaths of people who had previously tested positive for the novel coronavirus are recorded as having been caused by COVID-19. Also deaths are attributed to the novel coronavirus of people who were never tested for the virus but were assumed to be infected because either they had some symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, or others in the LTCH or hospital where they died had tested positive. This significantly inflates the numbers of COVID-19 deaths.

Furthermore, the new Ontario procedures deem all COVID-19-related deaths to be natural deaths. Therefore no autopsies are conducted for these deaths — even though they could reveal whether the people in fact died from COVID-19 or from another cause. The rules also appear to preclude the opportunity for removal of tissue or fluid samples for potential future examination.

Much of this runs contrary to recommendations released just nine months ago as part of the formal report on the Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-term Care Homes System.

Colloquially known as the Wettlaufer inquiry, the high-profile probe focused on causes of foul play and potential preventive measures after registered nurse Elizabeth Wettlaufer was given a life sentence for murdering eight people, attempting to kill several others and committing aggravated assault against another two. All but two of her victims were LTCH residents. The incidents took place in southwestern Ontario between 2007 and 2016 and only came to light when Wettlaufer disclosed them, unprompted, to a psychiatrist in September 2016.

Among the report’s recommendations relevant to carefully documenting the circumstances of death are 50 to 61. These call among other things for the replacement of the standard one-page, 10-question (‘Yes’/‘No’) Institutional Patient Death Record (IPDR) with an evidence-based resident death record. These would be filled out by the staff member who provided the most care to residents just before they died. Physicians, nurses and personal support workers who cared for the person would have input, as would family members.

Then the LTCH’s medical director, director of nursing and pharmacist, and the resident’s treating physician(s) or nurse practitioner all would receive a copy of the completed death record. They would be required to review it as soon as possible and bring any concerns they may have with death or the accuracy of the death record to the OCC and/or the Ontario Forensic Pathology Service.

The inquiry report also recommended the OCC consult with the deceased’s family or with the person who had decision-making power for the deceased before he or she passed.

Eighteen of the recommendations were implemented by February.

Instead, the new COVID-19 procedures keep the original one-page IPDR and add a two-page form called the Managing Resident Deaths Report (MRDR). [A jarring acronym.]

A MRD Team at the care home fills out both forms within a few hours of the death. The team members often are not present either at the time of death or during the previous day or days leading up to the death.

A member of the team electronically submits the IPDR and MRDR to the OCC, which immediately transcribes that information onto an electronic MCOD. The OCC then transmits it to the funeral home. The OCC does not share the MCOD with the care home.

(Ontario’s Vital Statistics Act was altered sometime before April 6 to allow death-registration documents to be transmitted via fax or a ‘secure electronic method’ by coroners, funeral directors and division registrars [municipal clerks]. The Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services and the OCC then created electronic versions of the MCOD and the burial permit.)

This option is also available for hospitals. According to the Q&A written by the OCC on the new rules for dealing with hospital deaths, the first-line approach is for the physician who treated the patient to fill out the MCOD within one hour of death.

If that physician is not available, the pre-designated Expedited Death Response Team (EDRT) [also jarring, since this could be read as referring to an expedited death rather than an expedited response to the death] at the hospital fills out an Expedited Death Report. This document is almost identical to the MRDR, except the title is different and ‘Hospital where death occurred’ replaces ‘Long-Term Care Facility where death occurred.’

The EDRT electronically transmits the report to the OCC. This should be done “within minutes, not hours,” according to the hospital Q&A.

When the OCC receives the MRDR and IPDR from an LTCH, or an Expedited Death Report from a hospital, the OCC staff use this information to complete the MCOD. They then transmit it to the funeral home. They do not send the death certificate to the hospital or LTCH.

Next, someone at the funeral home completes the Statement of Death. This is a one-page form that includes the name, age and former occupation of the deceased, the name of the person who pronounced the death, the name and address of the ‘proposed cemetery, crematorium or place of disposition’ and some other basic information. It does not list the cause of death.

The funeral home quickly sends via encrypted email or fax the completed Statement of Death and the MCOD to the local municipality, which then issues a burial permit. The burial or cremation or other disposition of the body then can proceed.

There is no information on the publicly accessible portions the BAO’s website about how much, if anything, the funeral homes are allowed to bill the provincial government and/or the estate of the deceased for each of these steps.

Approximately one week later the local municipality electronically transmits the MCOD to the Office of the Registrar General of Ontario.

Harry Malhi, a media-relations person for the Registrar General’s office, said in an emailed response to several questions that “generally, it takes approximately 6-8 weeks for the Office of the Registrar General to register a death once the registration documents [MCOD and Statement of Death] have been received.” Malhi also stated that “death registration and specifically cause of death information is considered personal information related to the deceased and is not available publicly.”

The Registrar General shares the information on each death with Ontario’s and Canada’s vital statistics offices. Aggregated death data and statistics are not available until at least one year later.

Over the Easter weekend, from April 10 to 12, Dr. Huyer and Carey Smith, who is the BAO’s CEO and Registrar, explained the new procedures via eight webinars to more than 1,000 people from the LTCH, hospital and funeral-home sectors.

Smith’s presentation emphasized the need to “accelerate the disposition of the deceased and to minimize storage between death and disposition.”

This “moves decedents from [the] healthcare [sector] to [the] funeral sector without delay to place them into care of people best-trained and equipped to handle them,” his presentation states. The new approach also “relieves [the] burden on healthcare – [allowing staff to] devote their attention to the living.”

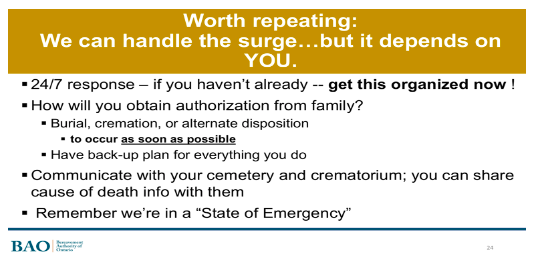

Smith observed (as seen in screenshot of slide 24, below) that the goal is managing “the surge.”

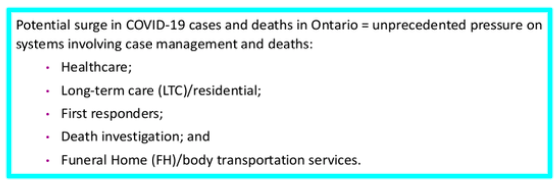

Dr. Huyer similarly highlighted the spectre of a fresh spike in morbidity and mortality, as shown in this screenshot from slide 7 of his presentation.

However, the vast majority of Ontario’s healthcare system has never been over-burdened by COVID-19-related deaths, nor has this been a likelihood.

Virtually all elective cases were cancelled or postponed by mid-March. This resulted in most hospitals being far less busy than normal, as documented in many media reports. The Financial Accountability Office of Ontario corroborated this in an April 28 report. And on May 8 the Ontario premier and minister of health announced the province is preparing to resume elective hospital procedures and surgeries.

There also has been no indication that more than a small handful of LTCHs in the province have ever had such rapid rates of resident deaths during a COVID-19 outbreak that the facilities’ overnight storage space was at risk of becoming over-filled.

There are additional facets of the new procedures that raise red flags.

One example is on the second page of the Q&A about the new rules for the LTCH sector. There, it states bodies must be removed from the LTCH even if the death requires a coroner investigation.

“Regardless of whether a death requires a coroner investigation, the movement of the resident to the funeral home by the funeral service provider will proceed.”

Thus there is no opportunity for an objective examination of the physical setting of the death.

Yet Dr. Huyer seems to see only upsides to the new rules.

“All of these things are added during this period of time to allow not only a timely approach but also an efficient approach to be able to ensure that people proceed to burial or cremation in a timely way without requiring additional storage space,” he said in the telephone interview.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Rosemary Frei has an MSc in molecular biology from a faculty of medicine and was a freelance medical writer and journalist for 22 years. She is now an independent investigative journalist in Toronto, Ontario. You can find her earlier article on The Seven Steps from Pandemic to Totalitarianism for Off-Guardian here, watch and listen to an interview she gave on COVID19 and follow her on Twitter.