Never Again: Hiroshima, Auschwitz and the Politics of Commemoration

Professor Ran Zwigenberg makes a case for revising the history of Hiroshima and its global connections and importance. Focusing on the little known episode of the 1962 Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March, he argues that the march was a unique point of convergence between multiple national narratives of victimization. The Peace March illustrates the emergence of a shared discourse of commemoration of WW II following the Eichmann trial and others, which agents like the marchers facilitated and which emerged from multiple Western and non-Western sources.

In 1962 a young Jewish American psychiatrist by the name of Robert Lifton visited the Hiroshima Peace Museum. Lifton described his visit to the museum in a letter to his friend David Riesman,

“I had seen many such pictures before…but somehow seeing these pictures in Hiroshima was entirely different…we left this part of the exhibit reeling…Both of us anxious, fearful and depressed–Betty [Lifton’s wife] to the point of being physically ill.”1

Lifton decided to stay in Hiroshima and help its survivors. His research greatly altered our understanding of Hiroshima and the psychiatry of trauma. It would be hard to find similar responses by visitors today. The Liftons’ reaction to the museum was not just a function of their encounter with the horror of Hiroshima but of the heightened awareness of the importance of the city in light of the global tensions that would bring the world to the brink of nuclear war that same year. The museum and Peace Park today are far calmer places. Perhaps even too calm. The message of peace, felt so urgently by Lifton, has lost its edge in Hiroshima. Italian journalist Tiziano Terzani captured the mood of the place succinctly when he wrote, “In Hiroshima…even the doves are bored with peace.”2 The serenity and passivity of the memorial begins right at the entrance to the museum, where a film opens with the words, “On the sixth of August, 1945, a nuclear bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and vast numbers of its citizens died.”3 There is no mentioning or way of knowing who dropped the bomb or what had led to the event. These words embody in them the entirety of the message of the memorial: Hiroshima is presented like the scene of a natural disaster, separated from any historical chain of events. Carol Gluck called this kind of narrative, “history in the passive voice.”4 In a world that still has over twenty thousand nuclear weapons, such serenity in the face of past and (possible) future horror is extremely troubling.

When I visited the memorial, forty years after Lifton, the Hiroshima Peace Museum’s passivity stood for me in sharp contrast to the shocking photos and evidence of destruction of that day. The words that framed the images seemed to be a part of an effort to contain the shock and anger a visitor might feel. The memorial message seemed an effort to counter the subversive potential of Hiroshima. Indeed, this was the case not just with the memorial. The survivors themselves, whose stories I heard, seemed restrained; their stories almost always ending with a plea for understanding and world peace. What I came to understand over the course of research on the topic is that the entire edifice of remembrance in and around Hiroshima was, consciously or not, built around containment. The very shape of the city and the spatial division between the island of Nakajima, where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park is located, and the rest of the city, suggest a much deeper division between the past and the present; as if Hiroshima wished to demarcate and distance itself from the past. It seemed to me that, as a visiting journalist once remarked, “People built this city to forget.”5Hiroshima’s memory, I realized, however, was never, with the possible exception of the late forties, actively suppressed. Rather, the principal argument of this work is that Hiroshima’s tragedy was rendered harmless to the status quo by the particular way it was remembered. Commemorative work in Hiroshima was largely used to normalize and domesticate the memory of the bombing. The bomb was presented not as a probable result of our reliance on science and technology but – in the words of the epitaph of the central memorial cenotaph – a mistake: a sort of temporal slippage into a darker time.6 Furthermore, Hiroshima’s sacrifice was supposed to somehow rectify this error, set history right and put progress back onto its “normal” course. The bomb therefore was presented as a transforming baptism, on one hand, and a rupture that must be healed, on the other. This phenomenon was not limited to Hiroshima. The effort to contain the bomb’s memory was profoundly shaped by the larger efforts of elites in the East and West to rebuild a postwar order and to reaffirm, the bomb and the concentration camps notwithstanding, belief in modernity and science.

Because of the nature of the tragedy and the enormous importance given to the efforts to formulate a proper reply to it, the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki came to possess important symbolic power. The bombing was thought to have bequeathed to Hiroshima’s victims a global mission and importance. This was synchronous with and influenced by a similar view of the place of the victim/witness in Holocaust discourse. In both discourses, the survivor was eventually elevated as the ultimate bearer of moral authority; what Avishai Margalit called “a moral witness.”7 This development was a direct consequence of the unprecedented nature of the tragedies and the failure of conventional means to represent and explain them. This had important implications for commemoration and politics in Japan and elsewhere, a phenomenon that went well beyond the confines of one nation or culture. As evidenced by Robert Lifton’s story, whose moment of shock in Hiroshima led him on to a career that impacted profoundly both cultures of memory, Hiroshima had an important role, now largely forgotten, in the making of global memory culture. However, the importance of Hiroshima was not appreciated by scholarship on either Hiroshima or the Holocaust so far (not to mention Nagasaki, which Hiroshima should not stand for and has a unique history of its own).

Thus, my recent book Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, (Cambridge University Press, 2014), has three main goals: first, to explain how and why Hiroshima’s memory developed the way it did. Second, to reinsert Hiroshima into the larger global conversation about memory and, three, to examine the many links between Hiroshima and “the world,” mainly through an examination of its links and comparison with Holocaust discourse in Israel and elsewhere. This is done, first, by examining the way the bomb and, to a lesser extent, the Holocaust, were explained, contained and integrated into the national and international narratives and ideologies which came before them and second, looking at the way that survivors reacted to (and sometimes produced) these discourses, leading to the emergence of the figure of the survivor in postwar Japan and the West. In the manuscript, I examine this development through both a comparative angle and through looking at the many connections of Hiroshima and Auschwitz. What I realized while researching this book is that the histories of Hiroshima and Holocaust commemorations are entangled histories. For a long time after the war these two tragedies were seen as twin symbols of modern failure; sites of industrial killing on an enormous scale, which might even serve as harbingers of future horrors to come. The symbolic connections between Hiroshima and Auschwitz were especially strong prior to the eighties when the enormous rise in importance of the Holocaust and the end of the Cold War caused Hiroshima to somewhat recede from our collective imagination. To examine the connections between Hiroshima and the Holocaust and the cross over of ideas and narratives, I chose two historical episodes: the history of psychiatry and trauma – focusing especially on the work of Robert J. Lifton and the history of an organization called the Hiroshima-Auschwitz Committee. This article focuses on the latter’s history.

|

The Hiroshima-Auschwitz Committee, a Japanese peace organization that tried to connect the two tragedies in its work for peace, no longer exists. Not many had heard of it when I started making enquiries into it in Hiroshima. This is not surprising as for the most part the organization ended up on a note of failure. Its biggest enterprise, the building of a grand Hiroshima-Auschwitz memorial (which I write on extensively in the book) was delayed for a decade and ended up in controversy with foreign governments protesting broken promises, accusations of missing donation money and Yakuza connections, and most of the articles for the museum – already on loan from the Auschwitz Museum and in Hiroshima, shamefully returned to Poland. Such failure, most of it the fault of the Committee’s bad choice of partners and unfortunate historical timing, obscures a fascinating history of exchange between Hiroshima and Auschwitz which dates from 1962.

In that year a pilgrimage by a group of Japanese activists to Auschwitz sought to connect the two places of tragedy for the sake of peace in a world, which under the threat of the Berlin and Cuban Missile Crisis, was teetering on the edge of nuclear Armageddon. The climax of the pilgrimage was in Auschwitz itself on liberation day when the young activists marched arm in arm with former prisoners of the camp carrying a banner of peace. But the roots of the march went back and encompassed events and decisions made in Tokyo, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Oświęcim and Jerusalem.

The Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March

On January 27, 1963, a particularly cold and snowy day, a mile-long procession to commemorate the eighteenth anniversary of liberation made its way from the city of Auschwitz to the site of the death camp. The procession was headed by four young Japanese men, among them a Buddhist monk and a veteran of the Japanese imperial army, Satō Gyōtsū. These men had traveled over 3000 kilometers, mostly by land, from Hiroshima. During their travels they visited numerous sites of World War II death and memory and met with scores of survivors. Indeed, one of the main goals of the four men, who had left Hiroshima about ten months earlier, was “to unite the victims and places of tragedy of the Second World War.”8 In a remarkable document issued by the organizing committee in Tokyo, the march’s organizers declared:

“We Japanese, as both aggressors and victims of the war, should have a special duty in calling for world peace… we, who are of young age, went through the bomb and occupation…but at the same time must reflect on the sin of aggression that we committed… thus we decide to set up on this march and: 1) to tell… as many people as possible about the horrors of Hiroshima and Auschwitz; 2) Record the suffering of different people we witness in various countries; and 3) to tell people about [Hiroshima and others’] suffering and hold peaceful gathering in all places we will be; 4) to make international connections based on the world religious conventions in Prague and Tokyo.”9

The Hiroshima Auschwitz Peace March (hereafter HAP) was one of a number of initiatives that responded to the crisis of the peace movement in Japan, which broke apart following the passage of ANPO (the US-Japan Security Treaty) and set out to spread Hiroshima’s message in the world. 1962, with the Cuban Missile Crisis and rising Cold War tensions on the one hand and the fracturing of the peace movement on the other, was a pivotal year for Hiroshima’s relations with the world. The HAP sought to use the power of hibakusha testimony and the experience of Hiroshima to prevent another world war. Uniquely, in doing so, they also sought to connect with other survivors of World War II.

This was lofty sentiment indeed. When the marchers set out on their journey they encountered cultures of commemoration very different from their own, with very different ethos and drawing very different lessons from World War II. Some of those lessons, as in Israel, were almost diametrically opposed to those that peace activists drew for Hiroshima. This caused more than a little anxiety and confusion for the marchers. At times, the HAP members found it hard to reconcile their own ideas, which developed in the context of Hiroshima’s commemoration culture, with what they experienced in other places. At other times, however, there was a remarkable understanding and surprisingly smooth exchange between HAP and other groups. What the HAP march illustrates is that the basic format of commemoration was quite similar around the world. Although the idea of a global “cosmopolitan memory culture” is of relatively recent vintage, and it is usually related to the “rise” of the Holocaust as a paradigm for commemoration, the HAP march showed that the globalization of WW II memory and the interplay of different war memories date as far back as the fifties.10 Indeed, it is doubtful if it was ever only local. The histories of war and commemoration are, to use Sebastian Conrad’s words, “entangled histories.”11 The HAP march serves as a lens through which we can examine these entanglements and connections between these different places of memory.

In all these different war memories the figure of the survivor-witness was a common feature. In Hiroshima and elsewhere, the development of the survivor-witness was the result of a convergence of factors both internal to the victims’ experience and external developments that turned the shame of being a victim into the pride of being a survivor. The idea of the survivor, which developed mostly separately in different places, was in the 1960s in the process of convergence. The HAP and groups it worked with, similarly to Robert Lifton and the discourse of trauma, were among the agents of this convergence. The HAP members again and again emphasized their will to tell and hear testimonies. They had an almost magical belief in the duty of the witnesses to war crimes to tell their story, and of testimony’s transformative power. Again, this was not limited to the HAP. The rise of witnessing was a global phenomenon and has been examined by a number of scholars, most notably Annette Wieviorka and Jean-Michel Chaumont in relation to Holocaust survivors.12 The HAP story demonstrates that this experience was shared beyond Europe. The war was a worldwide traumatic event. The forced silence that many victims encountered, the lack of judicial and other recourse, and the unresolved trauma pushed many to talk. In the face of what was impossible to fathom there was a need to tell one’s story or, to use Shoshana Felman’s words (drawing on Walter Benjamin), “in face of the abyss… the expressionless turn to storytelling.”13

The experience of survival and witnessing did not mean the same thing everywhere. The HAP encounters with survivors in Poland, Singapore, Japan and Israel show that along with much convergence of narratives and practices, there was also much divergence in meaning, leading to confusion and contradictions. Hiroshima’s ethos of the pure and forgiving survivor was not warmly received in Asia, where Japanese had not just been victims but also victimizers in the war. The HAP marchers were aware of this and even tried to make it a point of unique strength, as the declaration quoted above shows. Nevertheless, they continually struggled with this contradiction. Furthermore, the HAP solution to this problem, not unlike how Hiroshima City dealt with its own contradictions, was to use extreme abstraction and universalization of the experience of victimization. This was particularly evident in the way that not only Japanese but also Poles and others abstracted and idealized the real victims of genocide out of existence, replacing the Jewish victims of genocide with more noble sacrificial lambs for peace or the struggle against fascism. By their actions, however, the HAP and similar groups created a concrete connection between disparate but similar discourses. This globalization of the figure of the victim-witness enabled a convergence of the narratives and contributed, in conjunction with the Eichmann trials and other developments, to a process which would eventually lead to the “era of the witness.”14 In the pages that follow this story is told through the unusual encounters HAP marchers had with local memory cultures in Singapore, Poland and Israel, as well as the experiences of the marchers themselves in Japan; examining the interactions and entanglement of war memories that this unique peace march event produced.

Uniting the victims of the world’s sites of atrocity: the peace march departs

The idea to organize a pilgrimage to Auschwitz originated in discussions during the sixth annual All-Japan Gensuikyō meeting in Tokyo in August 1960. As part of this gathering, the representative of the Nihonzan-Miyohoji temple — a Nichiren sect temple in Chiyoda, Tokyo—Satō Gyōtsū, proposed an international peace march.15 Auschwitz was not yet proposed as a destination and nothing much came out of his proposal until another major gathering in Kyoto in July 1961, which brought together religious activists to discuss ways to achieve reconciliation and world peace. 16 The 1961 congress met at a time when the peace movement was fast falling apart and was one of the many initiatives that tried to bring it back together. Father Jan Frankowski, a Roman-Catholic Polish priest, was among those present at the conference and he, in conjunction with Satō and a journalist from the Osaka Yomiuri, Satō Yuki, seem to have been the first to initiate a call for forming a Peace Pilgrimage to Auschwitz.17 During the conference they were introduced to the other future members of the peace march: Kajimura Shinjo, Yamazaki Tomichiro and Katō Yuzo, who were all of different denominations and student activists, by YMCA Hiroshima General Secretary Ayuhara Wakao. Ayuhara, a bomb survivor and peace activist, also connected Satō Gyōtsū and Satō Yuki, and made the suggestion to start the march in Hiroshima.18 Besides Satō, all other participants in the march were students in their twenties from various Tokyo universities who were active in student circles.19

Much of the initial impetus for the march can be attributed to the post – ANPO mood within the Japanese peace movement. While the rifts and violence that accompanied the end of mass protest and breakup of the anti-nuclear movement led people like Satō and other religious leaders to look for reconciliation and avenues of non-violent protest, for many students, a feeling of depression and confusion ensued.20 Despite enormous counter-efforts, the conservatives passed the treaty and, as the students saw it, opened the way to a return of imperialism and repression, which, coinciding with rising cold war tensions, seemed imminent. We felt, wrote the HAP participants, “that something had to be done [to stop the rise of reaction] but we did not know how to proceed.”21 The solution found by both religious activists and students was to look outside of Japan.

As Hiraoka Takashi, a leading Hiroshima journalist (and future mayor) noted, the peace march was only part of a growing trend of international initiatives. In 1961, Earle Reynolds, an American peace activist residing in Hiroshima, in one of the first of these endeavors, organized a group ofhibakusha that traveled around the world and gave testimonies. Reynolds’s Hiroshima peace pilgrimage was launched in March 1962, and, in the same year, anti-nuclear activists formed a joint group that went to Accra and Moscow to attend international peace gatherings. These initiatives and the march, wrote Hiraoka, looking back on 1962, were making “the experience of being bombed the base (root) from which we could lead the peace movement out of the strife-ridden desert (fumō).”22 By 1962, the assumption of an organic link between the atomic bombings and the political goals of the peace movement had become a common strategy, in Hiroshima and elsewhere. For example, similar to the way Hiroshima reached out to Auschwitz, Hans Bonn, the mayor of the East German city Dresden, wrote to Hiroshima’s mayor in June 1961 calling for, “a partnership in the fight for peace and against rising militarism to transcend the divisions of East and West.” Hiroshima honored neither this nor a similar request from Dresden in 1963 with a reply. Making common cause with a city in the Soviet East Bloc was probably anathema, given Hiroshima’s own divisive politics of “peace”.23

This game of competing victimization took an unexpected twist when, as the peace march organizers were applying for Japanese passports, they were denied help by what they called, “pre-modern feudalist bureaucrats,” on the grounds that they “show unfair discrimination by going to a site of genocide by German soldiers in Auschwitz but not for the one committed by Soviet soldiers in the Katyn forest” (site of a massacre of Polish officers in 1940, which played an important role in Polish memory of victimization by the Soviets).24 Then as now, the right in Japan and elsewhere was disposed to reverting to the “counter-victim” discourse. As Alyson Cole pointed out in relation to “counter-victim” discourse in the United States, conservatives often claim for themselves the status of “true victims” by pointing out that their own victimization is forgotten and obscured by the leftist media.25German conservative historians would also play this game of “contextualization” during the Historikerstreit in the nineties. The Katyn episode shows a similar inclination on the part of Japanese conservatives, and is quite remarkable given the time and the context of Japanese political infighting. It demonstrates that the counter-victim discourse was there side by side with the victim discourse from the very beginning.

By January 1962, everything was ready for departure. In an interview with Chūgoku Shinbun, Satō declared, in what became a mantra, his desire “to deepen the connection between these two places of utmost suffering and tragedy in World War II.”26 Before the departure ceremony, Satō and the students visited the A-Bomb hospital and met with hibakusha representatives. From a sick girl at the A-Bomb hospital they received 3000 paper cranes, a symbol (through the martyrdom of Sasaki Sadako) of Hiroshima’s ultimate sacrifice and innocence, and they vowed to “spread the voice of Hiroshima and unite it with that of Auschwitz where untold numbers of Jews were murdered at the hands of the Nazis.”27 They left these cranes everywhere they went.28

Until 1962, references to Jews or Auschwitz had been entirely absent in the Hiroshima discourse. So, why Auschwitz? Why at this time? Rising tensions both domestically and internationally supply us with some context, and Father Frankowski supplies us with a concrete connection, but the timing of the march was crucial. It was the Eichmann trial—a global media event—that brought Auschwitz to public consciousness in Hiroshima as elsewhere. Indeed, according to Kuwahara Hideki, the head of the Hiroshima-Auschwitz Committee, it was the enormous publicity of the trial that first brought Auschwitz to the attention of Hiroshima’s activists.29 Yet, the Eichmann trial in Japan, and the Holocaust as a whole, was not quite what it was in Israel, Germany or the United States. This had important implications for the way the pilgrims and Japanese as a whole would view Auschwitz and the Holocaust.

Eichmann in Hiroshima: the Holocaust through Japanese eyes

The Eichmann trial was front-page news in Hiroshima and Japan as a whole.30 Eichmann’s capture in Argentina in a daring Mossad operation was headlined in the international press. The Asahi Shinbun called it “thrilling”, and a “suspense story.”31 The first reactions to the story expressed fascination with the “man in the glass cage,” and the “man responsible for the killing of millions.”32 Much of the trial coverage remained at this level, a sort of a-historical, human-interest drama with interesting characters and dramatic turns. Nevertheless, as the trial progressed, it touched upon fundamental issues: the Israelis’ right to judge Eichmann, the place of war responsibility and remorse, the issue of genocide, the plight of its victims and its contemporary importance, came to the fore. Rarely mentioned but always in the background was Japan’s own war. Discussions about the trial in Japan, in many ways, were more about Japan’s own guilt and its own self- perception than about Adolf Eichmann or the Holocaust. As David Goodman and Miyazawa Masanori argued, the Jews in Japan, a country with almost no Jews but with a developed discourse about them, often are used as a foil for domestic contestation, different players abstracting the figure of the Jew and using it for their own agenda.33 The way that Eichmann was perceived, and, in our case, the way that the marchers perceived Jewish survivors, was no different.

The first publication about the Holocaust in Japan was the 1952 translation of The Diary of Anne Frank. The diary was a runaway best seller; it is doubtful, though, how much information on the Holocaust or the Jews it conveyed to Japanese readers. Frank’s Jewishness is not emphasized and she is portrayed, more or less, as a victim of war in general rather than of racism and persecution or of the Germans. As Goodman and Miyazawa argued,Anne Frank’s Diary was popular in Japan precisely because it allowed the Japanese to relate to the Holocaust and WW II without tackling the hard historical realities.34 This was consistent with how the Japanese treated their own war as a whole. The Hiroshima figure of Sasaki Sadako, the child victim of the bomb, was also portrayed and conceptualized as the epitome of victimization by an abstract war and “the bomb.”35

There were some notable exceptions to this trend. In 1956, the anonymous editors of a translation of Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning directly connected the Holocaust and Japanese crimes on the continent. In a very different pairing than our pilgrims’ coupling of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, the editors commented, “there are two events that are so monstrous that they make one ashamed of being human… the first is the rape of Nanking in 1937… The second was the organized mass slaughter perpetrated in the concentration camps.”36 They went on to argue that knowledge of the Holocaust was absolutely essential in order for the Japanese to comprehend their own war guilt.37 Similar intellectual work on the Holocaust, like Jean Paul Sartre’s The Jew and the Anti-Semite or Eli Cohen’s Human Behavior in the Concentration Camps, appeared in 1957. Films such as the German Thirteen Steps or Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (Resnais would also make Hiroshima Mon amour) also had some impact.38 These works were important but as was typical with Western works on the Holocaust during these years, they concentrated mostly on the plight of political prisoners rather than specifically on the Jews qua Jews, and tended to blur the distinction between the concentration and extermination camps, as illustrated by Frankl’s editors’ reference to crimes in concentration camps (rather than death camps).39 The Holocaust was not seen as a separate phenomenon but was subsumed under the rubric of Nazi crimes. These crimes were, in turn, in more conservative publications (in Japan and the West), connected to Soviet crimes and the fight against totalitarianism. On the left, anti-fascist martyrs replaced the Jews, and Nazi crimes were portrayed as a “logical” continuation of capitalism’s crimes (a topic we will return to below). Racism, anti-Semitism and the historical peculiarity of the Holocaust were victims of this attitude.

This kind of Cold War logic can also be seen in many Japanese accounts of the Eichmann trial. The Yomiuri Shinbun, a right-of-center daily, argued in an April 1961 editorial that Eichmann was the product of totalitarianism: “… [One] can find Eichmann-like fanaticism in other dictatorships… this is the result of the same kind of group thinking when one person thinks like ten thousand.”40 Takeyama Michio, a liberal humanist (anti-communist), made a more nuanced argument regarding Eichmann’s defense, stating that he was just following orders, “Khrushchev answered [Eichmann’s] complaint (in his speech denouncing Stalin)… first, one says ‘I was just following orders’ … [then] he claims the nation was deceived.”41 Both Takeyama and theYomiuri editor were basically restating arguments from the immediate postwar era. Takeyama, in particular, was referring to the connection between Fascism and false consciousness. Takeyama mocks both Eichmann and many Japanese who claimed to have been deceived (dama sareta) by the militarists, thus feigning ignorance and innocence.

Takeyama, the celebrated author of the anti-war novel The Harp of Burma, had a distinguished track record in tackling Japanese war crimes. Takeyama was also one of the earliest commentators on the Holocaust in Japan. But Takeyama had a peculiar view of the Final Solution. Seeing it as an “irrational endeavor”, he traced it to theology and the scriptures; Hitler was basically fulfilling the anti-Semitism embedded in Western civilization and Christianity.42 Takeyama, like many other Japanese intellectuals, saw in fascism a sort of group madness. He saw the same madness taking place in Germany and in Japan. While, “Japanese had dementia, Germans became devils.”43 The disease of Nazism had pre-modern roots in religion. This view depoliticized Nazism and made it a sort of aberration. Like similar discourse that described the A-bomb as a mistake, it took its subject out of history and placed it in theology and psychology. “The Germans and the World,” wrote Takeyama, “lost their mental balance after WW I.”44 Unlike most commentators on the bomb, however, Takeyama did acknowledge that the problem was deeper than a momentary slip into darker times. Irrationality, which for him was the religious foundation of Western culture, was hidden within the very foundations of culture. “The foundations of Civilization,” Takeyama argued, “were shown to have been built on fragile foundations and were destroyed by this one push of fanaticism.”45 The implications for Japan’s own modernization and postwar embrace of Western culture are clear.

Unlike Takeyama, who acknowledged Japan’s own war crimes, other commentators seemed to treat WW II as a morality play in which Japan was nothing but a spectator. Other commentators employed the Jews’ postwar “vindictiveness” towards the Nazis (as opposed to Japanese “humanity” in forgiving the Americans) to extol their own moral position. The aforementioned Yomiuri editorial called on Jews to use the trial for “constructive purposes.” “We understand the feeling of the Jews,” the editors wrote, “but the memory of the cruelty … should end with this trial [as] we humans are trying to forget the cruelty of the war… eye for an eye is a Jewish tradition, but the world has to give up on it, to forget revenge and the past in order to establish a new peace for society. We should not throw stone after stone into the lake that tries to recover its serenity.”46 The writer’s clear implication was that Japan’s own lake had recovered its serenity via its re-invention as a nation of peace; a notion given concrete substance by Hiroshima’s “sacrifice for peace.”

“The eye for an eye” theme was repeated by many other commentators, especially after it became clear that Eichmann would be executed. Inukai Michiko wrote that she wanted a more universal solution. “I am not trying to save his life but I’m against this punishment.” Referring to Martin Buber, who opposed the death penalty, she wrote, “Israel should be one step above Nazis. We should refrain from killingEichmann.”47 A Vox Populi column in the Asahi argued on the same lines: “Israel should not kill him for revenge. If he is guilty of crimes against humanity, a death sentence is inhuman as well.”48 Another columnist wrote that the trial left him with the “aftertaste of public lynching,” and that, “Israel usurped the right to kill Eichmann.”49Inoue Makoto went perhaps to the furthest extreme, equating the Israeli court with Nazi crimes: “I can find no more words to defend the Israeli court than I can for [Eichmann’s crimes]. The psychology in this Kangaroo court is the psychology that makes war possible… [and] will lead humankind to destruction.”50

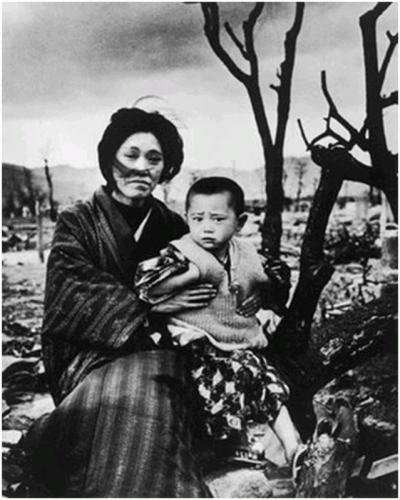

From Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, Hiroshima Panels From Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, Hiroshima Panels |

Also linking the trial to larger issues of war and peace, the Asahi wrote in a similar fashion as theYomiuri: “The trial should not be used for simple revenge but for constructive purposes… [It] should be used to establish internationally recognized laws and determine, across cultures, standards of cruelty… Beheading by samurai sword was cruel for Westerners but it was not [for us]… [Now] the entire world should recognize the use of nuclear weapons as cruel.”51 Another implied criticism of the Western Allies was a caricature published the same week showing the four nuclear powers marching in Nazi uniforms, goose-stepping in a Nazi salute and casting a shadow in the form of a swastika, with the caption “Eichmann’s replacements.”52 The Asahi’s complaint over Western “cultural misunderstanding” of Japan’s own war conduct, coupled with Japanese liberals’ admonishments of Israel for holding an “eye for an eye” mentality and for failing to live up to ideals of international peace and justice are, to say the least, hypocritical. This is not to say that familiar and painful issues regarding Japan were not debated here. But it seems that many felt superior to the Jews insofar as they themselves “overcame” their hatred to the Americans who had destroyed their cities.

If assertions of superiority were mostly implied in the papers, non-intellectuals had no scruples in making such statements outright. Robert J. Lifton conducted an interview with a technician and Hiroshima resident who reported that during the Eichmann trial, “a Japanese from Hiroshima went to Jerusalem [this would be Shikiba Ryuzaburō – a volleyball coach who went to Israel with a Japanese team], people there asked him why the Japanese don’t hate the people who dropped the A-bomb as they did, all their lives, hate Eichmann… Jewish people maintain that hatred and the wish to put their hands on the enemy. Now they tell the people of Hiroshima that we should have the same feeling.”53 With Eichmann and the A-bomb, the technician argued, [this] could not be avoided, as “they did these things on orders from superiors.”54The technician then went on to chide Koreans, using racist and derogatory language, over their supposedly inflated thirst for revenge and inability to forgive [Japan]. 55 Thus, both Koreans’ and Jews’ vindictiveness served here to highlight Hiroshima’s higher moral standards.

It must be said that some Eichmann related articles show a pretty detailed knowledge of the Holocaust and Israel. Reports discussed at length though, unfortunately did not directly comment on, K. Tzetnik and others’ testimonies. International (especially German) reactions, described the mood on the street and examined the judges’ backgrounds.56 However, most articles did not dwell on the complexities of the trial, the Holocaust or the Middle East conflict (the Palestinians are completely absent). Jews, as well as Germans, are used as abstractions against which Japanese commentators hold their own discussions about war responsibility, memory and history. This kind of attitude is consistent with the way many Hiroshima intellectuals used the Holocaust during the postwar years. Hiroshima and Auschwitz were seen as symbols of a break within the project of modernity. Kurihara Sadako, perhaps one of the most philosophically-minded of the hibakusha writers, wrote that Hiroshima and Auschwitz were the culmination of “progress,” as “mankind has stopped being mankind and completely became a machine.”57 For Ōe Kenzaburō as well, Hiroshima and Auschwitz represented a “decisive turn in civilization.”58 These writers and others were right to point to similarities and the shared logic of extermination and bureaucratically organized killing, but that was a fine line to walk. Hiroshima writers were sometime inclined to see their own predicament as worse or, as some did, to voice frustrations with the way Auschwitz has distracted attention from “their holocaust” or even suppressed it. Kurihara wrote that while many wrote about the Holocaust, “facts about Hiroshima were suppressed by the occupation.”59 Kanai Toshihiko, a well-known journalist, wrote in 1962, “The Hiroshima experience is not so well known…even though the scope of misery far exceeds that of Auschwitz.”60 But there were also many compelling works of art and literature, such as the Marukis’ Auschwitz murals, which came out of their Hiroshima panels and displayed profound sensitivity to the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Contemporary photo of Hiroshima. AP Photo/Shizuo Kambayashi. Contemporary photo of Hiroshima. AP Photo/Shizuo Kambayashi. |

Furthermore, not only Japanese but Jewish intellectuals as well connected Auschwitz and Hiroshima. Elie Wiesel, Nelly Sachs, and Primo Levi all made these connections. Levi, in a 1978 poem, The Girl-Child of Pompeii, speaks of “Anne Frank and the Hiroshima schoolgirl/ a shadow printed on the wall by the light of a thousand suns/ a victim on the altar of fear.”61 The connection between the sites is undeniable. Industrial killings, genocide and the nuclear menace are linked not just temporally, in that they all originated during WW II, but also through the very mind frames which reduced populations to equations of killings. Nevertheless, making these connections without proper contextualization also runs the risk of simplifying and abstracting these two tragedies beyond recognition. Especially in Hiroshima’s case, this could have troubling consequences as equating the carnage of Hiroshima and Auschwitz obfuscates the fact that Hiroshima was a major military center of a nation at war (which was also the Nazis’ ally and committed atrocities of its own), while the Jews did not do anything to the Germans. The pilgrims were actually confronted with this very question by an Israeli on the French vessel that carried them to Vietnam who pointed out that “in Auschwitz there were no combatants… [And] all were killed indiscriminately.” The pilgrims’ answer is not recorded.62 The pilgrims, however, were soon confronted with the reality of Japan’s war in Asia when they continued, after a brief stop in Saigon, to Singapore, where they were literally brought face to face with the results of Japanese terror on the continent. These encounters, which I expand on in the manuscript and related articles, mostly showed how different was Hiroshima’s remembrance culture from others around the world. In Singapore, the Hiroshima delegation was confronted with accusations of complicity in Japan’s crimes and with an actual site of mass killings of Chinese citizens, in Siglap, while in Israel, they were confronted with a very different memorialization ethos which challenged their view of the victim as a pacifist hero. But what were even more fascinating were the similarities and many points of convergence between Hiroshima and other discourses. These were on display most clearly in Poland, the HAP’s final destination.

Exchanging mementos of death: the Peace March arrives at Auschwitz

The HAP left Israel on November 6, 1962, with tensions over the Cuban missile crisis subsiding and the world returning to a somewhat more normal state. They traveled by boat to Greece where they met with the head of the local Salonika-Auschwitz Committee, Mr. Pinkhas. In Salonika, the HAP members met with survivors and learned from them about the deportations and suffering of Greek Jews in Salonika, whose Jewish past, following the Holocaust, was in the process of being eradicated by urban development and Greek nationalism, which was destroying synagogues and mosques and building over cemeteries.63 Pinkhas learned about the HAP member’s arrival from the International Auschwitz Committee (hereafter IAC) headquarters in Warsaw. The IAC and Jewish partisan organizations were also responsible for the warm welcome the marchers received in Yugoslavia and Hungary where they were received as semi-official guests. The connection with the IAC seems to have been made through Father Frankowski, back in 1961. The IAC, founded in 1954 by representatives of various survivor organizations, was the principal international organization that dealt with commemoration in Auschwitz.

Unlike Yad Vashem or Hiroshima, there was an active international component to commemoration activities in Auschwitz (foreigners were a big part of the process in Hiroshima but were never given an official role). Understanding this context is crucial for understanding why the Poles cooperated so readily with the HAP march and later with the commemoration of Auschwitz in Hiroshima. The Auschwitz site that the HAP would reach in January 1962 was already the third incarnation of the memorial. Founded in 1946, Auschwitz went through a Polish national phase in which it was presented as a site of Polish martyrdom, a Stalinist phase which eradicated almost all mention of Polish victimization and then, in the early sixties, shifted back to a Polish national emphasis but with an international component to it.64 This was part of the general post-Stalinist thaw and the move to a slightly more open “national communism” in Poland. The government sought to use international organizations to forward its ideological aims. But this was not a one-way street. The IAC lent its prestige to the government but also got a voice in the design of the Birkenau monument and Auschwitz’s character. The HAP mission fit in with the Polish government’s commemoration strategy and ideology. By connecting Hiroshima and Auschwitz, the HAP was highlighting the crimes of the American imperialists and connecting it with those of the German Nazis, exactly the kind of ideological connection which, although much less hyperbolic than during Stalinist times, still dominated Auschwitz’s message.65 As in Singapore, the HAP was once again becoming a tool in local memory politics.

The Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March in Israel (Source: Davar, October 13 1962) The Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March in Israel (Source: Davar, October 13 1962) |

As in Hiroshima and other places, in Poland as well there was a well-established victim-narrative. This was mostly about Polish victimization. The fact of Auschwitz-Birkenau being the “largest Jewish cemetery in the world,” with over one million Jewish dead in its soil, was completely marginalized.66 As Irwin Zarecka pointed out, Auschwitz for Poles “was not a symbol of Jewish suffering but a symbol of man’s inhumanity to man and a place of Polish tragedy.”67 In a similar way to Hiroshima, the Auschwitz museum sought to make it to a place of international tragedy but with an emphasis on a very specific Polish victimization. As in Hiroshima, which long discriminated against the Korean dead, Auschwitz as well was used as a tool for marginalization of the dead Jews. In Auschwitz, however, the Jews were an absolute majority of victims with about a million dead, in comparison to the horrendous but much smaller number of 75,000 Polish victims.68 In the immediate postwar and up to the nineties, Poles would speak of six million Poles who died in World War II; incorporating the Jewish dead as their own. That was also the number that was conveyed to the HAP while they were in Warsaw.69 Even in 1995, Kazimierz Smolen, the former director of Auschwitz who played a key role in negotiations with Japan, stated, “half of the Poles killed in Auschwitz were Jews and half ethnic Poles.70 The Jews, however, mostly did not survive and those who did left Poland. Poland was a harsh place for Jews in 1945-46, with returning Jews facing pogroms, stolen and destroyed property and political mayhem.71Commemoration was left for the Polish political prisoners, the church and the fledging communist regime, all of which could agree at this point on only one theme: Polish suffering.

Polish martyrdom, a loaded term connected to 19th century romantic nationalism and Catholicism, dominated Auschwitz’s message in the first few years, and would return in many forms since. Polish victims’ consciousness came out of Poland’s unique history of national failures and suffering. Poland, in the nineteenth century and after, saw itself as the “Christ of nations”; holding off the Russian hordes with its sacred mission to redeem the nations of Europe through its suffering and example.72 This idea was strengthened after the war. As in Hiroshima, Poles as well sought to rescue moral victory out of the jaws of defeat and humiliation. Poles saw themselves as having a postwar mission to serve as a beacon of warning against fascism under the slogan: “never again Auschwitz.” Creating a Polish martyrology made it essential to blur distinctions between Jews and Poles. One could not be the “Christ of nations” while being “only” victim number two. In addition, Poles saw themselves, with some justification, as being the next in line for the gas chambers, their “difference [from Jews] only in timing.”73 Whether the Nazis meant to exterminate the Slavs or not is rather beside the point. The Poles did suffer horribly and in their eyes, the gas chambers were a logical extension of that suffering. Polish prisoners of Auschwitz had a special place in this scheme as the ultimate bearers of the Polish cross. This cross, however, became increasingly an “antifascist and socialist” cross with increasing Stalinization in the late forties.

Former prisoners became especially important in Stalinist propaganda as having “a special right to criticize Anglo-American Capitalism.”74 Like their partisan counterparts in Israel and hibakusha in Hiroshima, they too enlisted in or were conscripted to serve the cause. Many former prisoners, however, were not comfortable with the crude instrumentalization of the camp and the state encountered much opposition from former prisoners whose “saint” status afforded them some leeway even within the Stalinist system. Auschwitz, commented one of them, “has become a peddler booth of cheap anti-imperialist propaganda.”75 This, together with the general “thaw” after the death of Stalin, enabled a change in Auschwitz, with much more autonomy for the staff and greater reliance on historical research and artifacts. This also meant, with the “national Communism” of Wladyslaw Gomulka, the return of the Polish victim narrative albeit in a modified form.

This narrative was clearly visible when the HAP came to Poland, where the HAP were treated as state guests and were taken around with their official minders to a whole array of commemorative and other events. The anti-fascism was spiced up with a good dose of Polish suffering. Father Frankowski, who met them at the station together with IAC representatives, gave the HAP a long speech, duly recorded by Katō, about Polish suffering through the ages, recounting how “during the last war, one in every five Poles died in the hands of the Germans,” claiming the Jewish dead as Poles.76 The HAP were taken to an exhibit of “survivors’ art” and met Poles from all walks of life who all seemed to speak in one voice, recounting the Nazis’ brutal treatment of Poland, its heroic resistance, and the wonderful job of reconstruction done in Warsaw, all under the banner of “never forget” and for the sake of “all of humanity.”77 “Out of the suffering,” declared one survivor artist, “we will create the future. We feel that the experience of those who were in the camps… could lead to the creation of a culture for all humanity.”78 This was language the HAP could definitely relate to. The Poles’ lofty idealistic talk of peace was standard discourse in the Eastern bloc. As we saw, the HAP were wary of identifying too closely with communist causes, however, they seemed to take it at face value when it came from survivors.

There was a strange reciprocity between the sides. In the art event where survivors’ drawings were shown, the HAP presented a painting of the bombing done by school children. Upon hearing survivors’ stories, “they reciprocated with stories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” and when they received artifacts and human remains from the Auschwitz memorial “they presented a charred roof tile from the ruins of Hiroshima [in return] to be placed in the cenotaph in Auschwitz.”79 The matter-of-factness of these exchanges and the way they are reported on as natural and desirable, demonstrate the common language of commemoration both places of death shared. The fact that this language – the testimonies, use of art, enshrining of ashes in cenotaphs, and the relic-like status of remains — evolved separately, without cross-reference and in completely different cultural and historical settings, is quite astonishing. This convergence points to the emergence during these years, out of separate strands, of a common victim-witness or survivor narrative. The common frame of reference for both sites was commemoration of soldiers in general and WW I in particular. As James Young, Harold Marcuse and others have demonstrated, within interwar Europe, commemoration developed as a genre of sorts.80 But what happened after WW II was different. The HAP demonstrates the globalization of this language after the war and was one of its agents; it literally carried elements of commemoration – in the forms of Auschwitz and Hiroshima remains — from East to West.

The most bizarre part of this exchange came after the marchers’ arrival at Auschwitz, when, following the ceremony, they received from Hołuj, a “present of human hair, cloth, shoes, and a tin of Cyclon B” to be taken to Hiroshima.81 Following this, Satō received “the remains (bone ash – ikotu) of the 4,000.000 (sic)… so the tragedy of Hiroshima and Auschwitz will never return (repeat).”82 The ashes were supposed to be taken back to Hiroshima and be buried together with the ashes of the Hiroshima survivors “forever uniting the victims.” 83 This final act of “exchanging mementos of death,” as the Chūgoku Shinbun, called it, sealed the pact between Auschwitz and the HAP.84 This was neither the first nor the last time the dead were physically enlisted in the service of politics in Auschwitz. During the April 1955 ceremony ashes from camps across Europe were brought by different delegations of survivors, uniting the ashes of victims across Europe in a highly liturgical act.85 Ashes from Auschwitz and other camps were also sent to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, in another highly symbolic act, which, this time returned the Jewish victims “home” to Zion.86 The Auschwitz Museum would, on at least one other occasion, use ashes to cement ties with other organizations. In another act of “death diplomacy,” a 1972 delegation to Bologna, which attended a ceremony to commemorate the Nazi massacres of Italian civilians in Marzabotto, also brought with it a can of ashes to be buried together with the Italian victims.87 Neither in Marzabotto, nor in Hiroshima, was the ashes’ (very probable) Jewish identity mentioned. On the contrary, these remains were universalized and robbed of any personal or other identity. In order to become the quintessential symbol of an alliance of victims, they had to be abstracted and taken out of any context. This left no place for the uniqueness of the Jewish tragedy, let alone for Roma and other more marginalized victims. This was much the same trajectory that the whole of the HAP enterprise had to follow, from the particular to the universal, from the concrete to the ideal. This also allowed various local interest groups to use the HAP mission for their own needs. The result was that, for all its lofty and good intentions, far from being an alliance of victims, the HAP journey actually participated in marginalizing and obscuring the experiences of other, less powerful groups of victims.

Conclusion – the Founding of the Hiroshima Auschwitz Committee and the mobilization of solidarity

Even in Hiroshima, from which the HAP derived its rhetoric and message, abstraction of victimization on the level practiced by the HAP proved impossible in the face of local memory politics. Upon their return to Hiroshima in August 1963, Satō presented the ashes and other remains to mayor Hamai, requesting that they be interned in the Peace Park. The mayor, in the presence of a representative of the Polish embassy and other dignitaries, respectfully received them, only to return them the following week.88 Hiroshima City, as we saw, was in no mood for controversy. Hiroshima City argued they had “no space” for the remains and that, for now, it would not be possible to erect any kind of new memorials in the Peace Park.89Commemoration in Hiroshima was moving away from anti-nuclear activities and into an emphasis on solemnity and “silent prayer.” As far as the HAP were concerned, the city, already accused by conservatives of being sympathetic to radicals, was wary of receiving these “mementos” from a communist country. Although Satō and the rest of the HAP desperately tried not to be associated with communism or any other kind of politics, eventually they could not escape it; their abstract victim turned back into a socialist hero that Hiroshima, in its current political mood, could not accept.

This led to the rather awkward question of what to do with the remains. Yamada and Satō contacted Kuwahara Hideki, who headed the Hiroshima Religious Association and together they issued a call for men of faith to help them deal with the situation. Satō Tetsuro from the Hiroshima Mitaki Buddhist temple then stepped forward and offered to keep the remains. The following month Satō Tetsuro, Kuwahara, Yamada and others conferred and decided to set up a permanent body which would raise funds to erect a monument at the temple for the victims’ ashes.90 In October, representatives from the Religious Association, hibakusha organizations and other peace groups, in the presence of Polish officials, met at the Prefectural Medical Association Hall in downtown Hiroshima and created the Hiroshima-Auschwitz Committee. The committee’s goals were: “1) to introduce [to the world] the true state of Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Auschwitz victims; 2) To erect a final resting place for the ashes of Auschwitz victims brought back by the Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March; 3) To uphold (promote) the goals of the international peace appeal movement.”91

The Hiroshima Auschwitz Memorial in Hiroshima where the Auschwitz remains were enshrined (photograph by author). |

In this act, the Hiroshima Auschwitz Committee (HAC) institutionalized the “victim diplomacy” of the HAP. The HAC now embarked on a grand scheme to develop and expand these connections. One of its first acts was to enshrine the remains received from Auschwitz at a shrine in Hiroshima. This was part of a much larger worldwide trend in which victims of WW II came to hold a special place in global moral discourse as witnesses of the unspeakable. The idea that survivors had special insight or moral authority should not be taken for granted; it has a complex, non-linear and transnational history. Much of it can be traced to the Eichmann and other trials, but they do not tell the whole story. The HAC represents a significant piece of this puzzle. In the HAC and the HAP journey, one could see a convergence of sorts, of different local memory strands in which the victim/survivor came to hold a special role. Whether it was the hibakusha in Hiroshima and their role in uniting a fractured peace movement; the national (multi-ethnic) victims in Singapore, or anonymous victims of fascism in Auschwitz, all had survivors stepping up and using their victimization as a tool and, more crucially, abstracting and turning the experience of mass death into a unifying experience. In both Hiroshima and Auschwitz this was also an experience that would have international significance and implications. The exception was the particular and peculiar victim discourse in Israel, which did not seek an international role for itself. The Jews’ emphasis on the ethnic character and anti-Semitism of Nazi persecution did not fit in with the priorities of either Hiroshima or Auschwitz. They were left out; even their dead were now instrumentalized and carried as a “memento of death” between the “places of tragedy.” This was consistent with the way Japanese commentators saw the Jews and the whole drama of WW II and genocide outside of Asia during the Eichmann trial, and was evident in the way the HAC and Hiroshima in general dealt with others’ tragedies in the next three decades of its existence.

This article was adapted from the introduction and chapter 5 of my manuscript, Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, (Cambridge University Press, 2014). A different much extended version appeared at “The Hiroshima-Auschwitz Peace March and the Globalization of the Moral Witness,” Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust, Vol. 27, No. 3 (2013), pp. 195–211. I thank Cambridge University Press for generously agreeing to let me use this material here.

Ran Zwigenberg is assistant professor of history and Asian Studies at Pennsylvania State University. He is the author of Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Notes

1 Robert Lifton to David Riesman, 10April 1962, Box 15, Folder 8 (1962) Robert Jay Lifton papers. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. (NYPL- MSA).

2 Quoted by Ian Buruma, “The Devils of Hiroshima,” in the New York Review of Books, 25 October, 1990.

3 See Daniel Seltz, “Remembering the War and the Atomic Bombs: New Museums, New Approaches,” Radical History Review, No. 75, (Fall 1999), p. 95.

4 Carol Gluck, “The Idea of Showa,” Deadalus, Vol. 119, No. 3 (Summer 1990), pp. 12-13.

5 The quote is from visiting Nigerian Journalist named James Boon, who told a Japanese colleague, “People built this city in order to forget about the bomb…[they] are trying really hard to live just like people in other cities.” Cited in the Yo miuri Shinbun, 18 June 1962.

6 The epitaph, it must be said, has historically raised a fair share of controversy. It states, according to Hiroshima City’s official translation “Please rest in peace for we shall not repeat the mistake” (Yasuraka ni nemutte kudasai, ayamachi ha kurikaeshimasenu kara). According to (Saika Tadayoshi, the framer of the epitaph (according to a note in his handwriting in the archives), “Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil.” Who is the “we” and whether it was an “evil” or an “error” or “mistake,” have been a topic of great controversy since. The epitaph was vandalized a number of times, most recently in 2005 by a right-wing activist.

7 Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 182.

8 “Hiroshima- Auschwitzu Heiwa Koshin,” Newsletter No. 1, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park Archive, Kawamato Collection, Box 38, folder 1, No. 911.

9 Ibid.,p. 1.

10 Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider, “Memory Unbound: The Holocaust and the Formation of Cosmopolitan Memory,” European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 5, no. 1 (2002), pp. 1063-1087.

11 Sebastian Conrad,” Entangled Memories: Versions of the Past in Germany and Japan, 1945-2001,”Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 38, No. 1, Redesigning the Past (Jan., 2003), pp. 86.

12 Jean-Michel Chaumont, La Concurrence des Victimes: Génocide, Identité, Reconnaissance (Paris : La Découverte, 2002); Annett Annette Wieviorka,The Era of the Witness (Cornell University Press, 2006).

13 Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century, (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 14.

14 The phrase is from Annette Wieviorka’s The Era of the Witness.

15 HAP Newsletter I, P 3.

16 Ibid.,p. 2.

17 Interview with Kuwahara Hideki, Hiroshima, 2 July 2010. Kuwahara was the head of the Hiroshima Auschwitz committee from its founding in 1962 and was involved in the HAP as well. Kato Yuzo and Kajimura Shingo, Hiroshima-Auschwitz Heiwa Koshin: seinen no kiroku, (Tokyo: Kobundo, 1965), p 168; Jan Frankowski and others who were involved in organizing the march (like Satō,Yamada and Kuwahara) were also involved in the World Federalist Movement through which they achieved most of their institutional support. See Yamada and Kuwahara’s recollections in Sekai renbō undō hiroshima niju go nen shi iinkai (ed.), Sekai renbō undō hiroshima niju go nen shi, (Hiroshima: Kawamoto, 1973), pp. 138,162 .

18 Interview with Morishita Mineko, Hiroshima, 2 July 2010. Morishita is the acting secretary general of the Hiroshima Auschwitz Committee.

19 Katō, who later became a Professor of Chinese History, denies in his memoirs any political involvement in the student movement. Although he wrote a book about the march in 1965, which appears in his resume, Katō also brushed out the peace march from his autobiography. He presented it as a student trip (or poverty trip-bimbo na ryoko), on which he embarked with three friends. He does not acknowledge any connection to the peace march or any political activities. Katō refused to speak to me about the subject for reasons that are not clear to me. His 1965 work, however, co-written with Kajimura (whom he also does not give credit to in his list of publications), is quite specific about his involvement in demonstrations and other activities. See his, Shiken to taiken wo megutte, in Yokohama shiritu daigaku ronsō jinbun gakukeiretu, Vol. 54 No. 123 (2003), p. 54.

20 Satō was very bitter and pessimistic about the peace movement. He rightly saw a split in the movement as imminent and decried the mindless rush to violence and sloganeering among his colleagues who had “violence, recklessness and rioting as their three sacred regalia,” referring ironically to the emperor’s regalia. Katō and Kajimura, p.13.

21 HAP Newsletter I, p. 5.

22 Chūgoku Shinbun, 22 December 1962.

23 Chūgoku Shinbun, 15 June 1961. Dresden sent another message on 6 August. Coventry in the U.K. as well sent a message to Hiroshima, “wishing to become one of 15 ‘world peace cities.’” See Chūgoku Shinbun 6 August and 21 September 1961.

24 HAP Newsletter I. p. 10: Until 1964 Japanese were not permitted to travel freely abroad, the government being wary of foreign currency leaving the country. Thus, the marchers had to get special permission to leave Japan.

25 Alyson M. Cole, the Cult of True Victimhood: From the War on Welfare to the War on Terror (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007), pp. 8-9.

26 Chūgoku Shinbun, 6 February 1962. Sasaki Sadako was a child victim of the A-bomb. She famously tried to fold a thousand origami cranes before her death, but failed. Children from her class were joined by thousands throughout the world after Sadako’s story was popularized worldwide through the work of Austrian writer Karl Bruckner in his work Sadako will leben.

27 Ibid; Chūgoku Shinbun, 7 February 1962.

28 The Yomiuri (English edition), 5 August 1963.

29 Kuwahara interview. 2 July 2010.

30 The Yomiuri Shinbun had 192 stories concerning Eichmann in 1962 alone. The Chūgoku Shinbun, had around fifty. There were as many references for the Holocaust that year as there were in the Chūgoku Shinbun, for the whole fifties’ decade.

31 Asahi Shinbun 14 June 1960.

32 See for instance Chūgoku Shinbun, 24 March 1961 and Yomiuri Shinbun 7 March 1961

33 David G. Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa, Jews in the Japanese Mind: The History and Uses of a Cultural Stereotype, (New York: Lexington Books, 2000), pp. 18-19.

34 Goodman and Miyazawa, pp. 139-140.

35 The Anne Frank story was connected to Sasaki Sadako’s. Both figures, as David Goodman and Miyazawa Masanori point out, served to de-historicize and de-politicize the Holocaust and Hiroshima. American responsibility for Sasaki’s death was not mentioned. In the case of Anne Frank, it was not only in Japan, but also in the U.S. and Europe that Anne Frank’s Jewishness was obscured. For marketing and other reasons, Otto Frank, Anne’s father, was eager to promote her image as (an almost American) “every-girl.” The universalization and de-Judaization of Anne Frank was particularly noticeable in Germany For a comparison, see Roni Sarig, “Sadako Sasaki and Anne Frank: Myths in the Japanese and Israeli Memory of WW II,” in War and Militarism in Modern Japan: Issues of History and Identity, edited by Guy Podoler and Ben-Ami Shillony (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2009), p. 172.

36 Goodman and Miyazawa, p. 140.

37Ibid. 141.

38 Ibid., p.142.

39 The concentration camps where most political prisoners were kept received much attention, together with the political prisoners – heroes of the resistance, in early postwar societies while the death camps, where mostly Jews perished and which had only a few survivors, received much less coverage. See Samuel Moyn, A Holocaust controversy: the Treblinka affair in postwar France, (Waltham, Mass: Brandeis University Press, 2005)

40 Yomiuri Shinbun, 26 April 1961.

41 Asahi Shinbun, 16 December 1961.

42 Goodman and Miyazawa, p. 146.

43 Asahi Shinbun, 16 December 1961.

44 Ibid.

45 Asahi Shinbun, 6 April 1961.

46 Yomiuri Shinbun, 14 April 1961.

47 Asahi Shinbun, 16 December 1961.

48 Asahi Shinbun, 17 December 1961.

49 Asahi Shinbun, 2 June 1962.

50 Quoted in Goodman and Mizawa, p. 152.

51 Asahi Shinbun, 12 April 1961 .

52 Yomiuri Shinbun, 11 April 1961.

53 Robert Jay Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (University of N. Carolina Press, 1991) pp. 321-322.

54 Ibid., p. 322.

55 Ibid.,pp. 322-323.

56 See for instance, Chūgoku Shinbun, 11 April 1961. The last discussion included a fascinating and nuanced account of Judge Landau’s involvement in an earlier case, the Kfar Qasim massacre, where Landau established the judicial principal of disobeying immoral orders.

57 John Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995) p. 10.

58 Ibid.,p. 19.

59 Kurihara Sadako, “Hiroshima no bungaku o megutte: aushiwitzu to hiroshima,” in Oda Makoto and Takeda Taijun (ed.) Nihon no genbaku bungaku(Tokyo, 1983), p. 258.

60 Goodman and Miyazawa, p. 177.

61 Ibid.

62 Katō and Kajimura, p. 9.

63 Out of a population of 50,000, there were less then 1,000 Jews left in Salonika. HAP Newsletter 5, p.10; Also Mark Mazower, Salonica City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews 1430-1950 (London, Harper Collins Publishers, 2004).

64See Jonathan Huener’s introduction to Auschwitz, Poland, and the Politics of Commemoration, 1945-1979, (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003).

65Huener, Auschwitz, p. 92.

66 Ibid., p. 34.

67 Iwona Irwin-Zerecka, “Poland after the Holocaust,” in Remembering for the Future: Jews and Christians During and After the Holocaust, (Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1988), p. 145.

68 Jonathan Webber, “Personal Reflections on Auschwitz Today,” in Teresa Swiebocka and Jonathan Webber (ed.), Auschwitz: A History in Photographs(Bloomington:University of Indiana Press, 1993), p. 283.

69 Katō and Kajimura, p. 174; HAP Newsletter 5, p. 15.

70 Kazimierz Smolen, “Auschwitz Today: The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum,” in Auschwitz: a History at Photographs, p. 261. Smolen makes this outrageous remark just a page or so before emphasizing the solidarity of Poles and Jews. The incorporation of the Jewish dead as Polish citizens is not unique to Poland. Israel as well annexed their memory and claimed the Jewish dead as its own. The victims were treated as martyrs for the state, who somehow gave their life so that Israel would be born. There were even serious discussions of giving Israeli citizenship ex post facto to Holocaust victims, most of whom were certainly not Zionists. Israel, however, where most survivors lived, had some claim to the Holocaust, whereas in Poland, where Jews were killed in the thousands after the war and enormous amounts of Jewish property were expropriated with no compensation, this usage of the dead was particularly disturbing.

71 See Jan T. Gross, Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland After Auschwitz. (New York: Random House, 2006).

72 Huener, Auschwitz. p. 49.

73Ibid., 54.

74 Ibid., p. 80.

75 Ibid., p. 112.

76 Katō and Kajimura, p.175.

77 Ibid. pp. 169-174.

78 Ibid., 175.

79 The Yomiuri (English edition), 5 August 1963.

80 Harold Marcuse, “Holocaust Memorials: The Emergence of a Genre,” in American Historical Review (Feb. 2010): James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993) I include Israel in this genre. Although Young and others look at memorials through a national prism, as Marcuse points out there are transnational trends (for instance towards abstraction from the sixties on), which defied national and ideological boundaries.

81 The Yomiuri (English edition), August 5, 1963. These were to be the basis of an exhibition in the Peace Park.

82 Katō and Kajimura, p. 190, the figure of four million was the accepted figure in Poland.

83 The Yomiuri (English edition), August 5, 1963. The quote is from the Chūgoku Shinbun, 6 February 1963; HAP Newsletter 5 and Katō and Kajimura also discuss the Auschwitz ceremony at length.

84Chūgoku Shinbun, 6 February 1963

85 Huener, Auschwitz, p. 117.

86 Mooli Brog,” Yad la’hayalim ve’shem lachalalim: nisyonot ha’vaad ha’leumi lahakim et yad vashem: 1946-1949, Katedra, No. 199 (September, 2005), pp. 116-117.

87 I thank Marta Petrusewicz, a Professor at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York, who was then working as an Italian interpreter for the delegation, for this reference. According to Harold Marcuse, there were quite a lot of ashes circulating around Europe at the time. The origin of this custom is obscure but it seems that it started right after the war. Survivors leaving Buchenwald in mid-1945 took eighteen urns of human ash with them to create memorials around the world. The 1949 Hamburg-Ohlsdorf memorial has 105 urns of ashes in it. See Harold Marcuse, “Das Gedenken an die Ver- folgten des Nationalsozialismus, exemplarisch analysiert anhand des Hamburger ‘Denkmals fu ̈r die Opfer nationalsozialistischer Verfolgung und des Widerstandskampfes’ ” (M.A. thesis, University of Hamburg, 1985), 59 (citing Hamburger Volkszeitung, May 3, 1949), 96–98; Some took the use of ashes a step too far. There were a couple of incidents involving victims’ ashes in Dachau and Flossenbuerg. In Dachau, the curator of the exhibition in the crematorium was accused of selling human ashes to visitors and was fired. (Private correspondence with Marcuse, November 7, 2010).

88 Chūgoku Shinbun, 8 August 1963; Kuwahara Interview.

89 Ibid.

90 Kuwahara interview.

91 Chūgoku Shinbun, 18 October 1963.