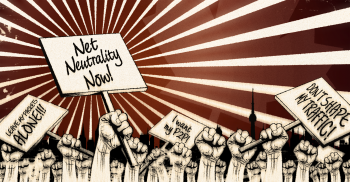

Net Neutrality: New Threats, Old Illusions

To a large extent, the notion of net neutrality has been a greatly promoted illusion. Net content is heavily restricted in numerous countries by legislative and executive direction. An amusing reminder of this took place a few weeks ago when a Chinese digital expert, on being interviewed on the CCTV network, claimed he had no access to Facebook but was still happy to discuss the practices and content of the network.

According to the Open Internet Coalition, the founding principle of net neutrality entails “keeping the hands of several network operators – AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast – off the Internet, preventing them from taking steps to change the basic open nature of the Net that has led to its success.”

The US Congressional Research service offers its own definition, admitting that, even if there is no single one doing the rounds, it would still “include the general principles that owners of the networks that compose and provide access to the Internet should not control how consumers lawfully use that network; and should not be able to discriminate against content provider access to that network.”[1]

Threats to net neutrality tend to be either dramatic assaults on the entire concept through government interference, or a corrosive process of backdoor incisions. In October 27 last year, by way of example, the European Parliament rejected amendments that would have made it a very difficult proposition for internet companies to toy with legal online content. The tendency to permit specialisation on matters related to content, and the way these are supplied, leads to the creation of tiers, the very levels deemed problematic to ideas of neutrality.

In the United States, the Federal Communication Commission has tended to keep vigil over encroachments on net neutrality under Title II of the Communications Act. The section empowers the FCC to prevent internet service providers to preference providers on business or political preferences.

In 2015, the FCC ruled in favour of a free and open Internet, though this far from settled the issue. The rules restricted internet providers from blocking access to website and apps, stifling traffic speed, and offering the sale of fast lanes.[2]

The right-wing shock jock fraternity have had issues with such powers. For them, net neutrality provides the basis of control of a different sort, overseen by the FCC. According to Glenn Beck of Fox News back in January 2010, the FCC wanted “net neutrality with Obama. That’s the big push. Net neutrality, it’s a way to control voices.” Ever the paranoid inventive, Beck had previously suggested that net neutrality was the bastard child of Marxists.

Donald Trump, the US President-elect, took the fairly standard view many conservative reactionaries have, formulating it on such outlets as Twitter. In 2014, Trump tweeted that, “Obama’s attack on the internet is another top down power grab. Net neutrality is the Fairness Doctrine. Will target conservative media.”[3]

The Fairness Doctrine reigned at the FCC from the 1940s to 1987, involving the requirement, long loathed by some media outlets, to devote some programming to controversial issues of public importance, and permit the airing of opposing views on those topics.[4] With its revocation in 1987, the conservative talk show circuit sizzled with unfettered glee.

Not all criticism can be saddled to the Fox News circuit, with its singular brand of delusionary mania. Packet networks, according to Martin Geddes, can never be neutral. Its evil twin, discrimination, leads to “a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between the international and operational semantics of broadband.”[5]

Geddes suggests that science and engineering is the problem here, and that can only be resolved by resources that assist scheduling. Performance tends to be arbitrary; specialised services are illusions, there being no objective definition of what they are; and fast lanes are already a reality.

Much of the opposition (or support) of such neutrality is dependent on which part of the service industry one is considering. Internet providers tend to oppose the neutrality concept in the historical sense. Those providing streaming services, and tech companies, prefer it.

An example of the latter is Google, which maintains that “the innovation that makes the Internet awesome” would be threatened if ISPs could “block some services and cut special deals that prioritize some companies’ content over others.”[6]

Trump is hardly going to be troubled by the nature of such semantics. He has left the business of attacking the concept of net neutrality in the hands of Jeffrey Eisenach and Mark Jamison, who will run the FCC transition team.

Eisenach’s colours are firmly pinned to the mast of Verizon Wireless, where he has been a paid consultant, while Jamison runs the Public Utility Resource Centre at University of Florida, and is reported to be a former lobbyist for Sprint.[7]

To that end, the issue here is one of degree, and not even Jamison suggests doing away with a process of resolving disputes within the market.[8] Eisenach prefers to see a jungle out there, with net neutrality simply benefiting one pack of hunters, the “one group of private interests” enriching “itself at the expense of another group by using the power of the state.”[9]

Given that Trumpland is bound to feature ways that money can be wrung from the net, riding on the back of such rhetorical fancies as innovation, the big telecommunications providers may well take their chances.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes

[1] http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS22444.pdf

[2] http://www.theverge.com/2015/6/12/8771155/net-neutrality-rules-now-in-effect-fcc

[3] https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump/status/532608358508167168?lang=en

[5] http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/10/27/eu_ignore_the_net_neutrality_and_choose_science_instead/

[6] https://www.google.com/takeaction/action/freeandopen/index.html

[9] https://www.aei.org/publication/theres-nothing-neutral-about-net-neutrality/