History of World War II: The Nazi-Soviet War Was Destined to Become a Long War, 80 Years Ago

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg.

***

During the fighting in the Soviet Winter Campaign, in mid-February 1942 the German Army had recovered its poise, as the situation stabilised for the invaders. Across the Eastern front, the Germans were able to hold on to most of the territory they had captured by early December 1941.

Astride the Russian cities of Rostov-on-Don and Moscow, where the Germans had received some of the heaviest hits of the Soviet Army’s winter counteroffensive, the Wehrmacht had only fallen back between 50 to 150 miles (1). The Germans avoided the disaster that had struck Napoleon’s invasion force, during their 1812 attack on Russia.

The Grande Armée failed to get through its first winter on Russian terrain, suffering complete defeat in December 1812. The Germans would survive 3 winters of fighting on Russian soil, a remarkable feat of arms. By May 1944 at their closest point the Germans were 290 miles from Moscow, while the Soviets were 550 miles from Berlin at that time. For example the Russian city of Pskov, 160 miles south of Leningrad, was not liberated by the Red Army until 23 July 1944. (2)

Military analyst Donald J. Goodspeed wrote that the German performance, in the winter of 1941-42, proved to be “much more significant than all the previous German victories” (3). This was because the Wehrmacht had prevented a collapse along the front, ensuring that the Second World War was now going to be an extended conflict – it would rumble on for considerably longer than “the Great War” (World War I), resulting in far more bloodshed and destruction than its predecessor.

Though the Nazis would be beaten in 1945 and Germany occupied and dissected, the weight of the blows they inflicted on the Soviet Union were a decisive factor in that state’s eventual demise in 1991. English historian Chris Bellamy wrote that Soviet Russia did not fully recover from the struggle with the German war machine and “was a long-term casualty of the Great Patriotic War” (4). It could be argued, therefore, that the conflict was not an unmitigated defeat for Hitler’s regime. Soviet military journals also state that the victory over the Nazis was achieved at a cost that was too great. (5)

Image on the right: Portrait photograph of Georgy Zhukov (Licensed under the public domain)

The Red Army’s counteroffensive of 1941-42 has often been regarded, through the decades, as a watershed Soviet triumph; but as Marshal Georgy Zhukov outlined in his memoirs, the reality on the ground does not support these claims. Between January to March 1942, the Germans inflicted more than four times as many casualties on the Red Army than the Wehrmacht had suffered, 620,000 losses as opposed to 136,000 (6). Zhukov described as “a Pyrrhic victory” the outcome of the Soviet counterattack. (7)

To use a sporting analogy, had the Nazi-Soviet War constituted a boxing match the Germans would have won by some distance on points scored. After 3 months of fighting, at the end of September 1941 the Soviet Army had suffered personnel losses of “at least 2,050,000”, while German manpower losses by then “numbered 185,000”, British historian Evan Mawdsley highlighted. (8)

From September to December 1941 the Soviets suffered 926,000 fatalities while, in the final quarter of the year, from October to December 1941 the Germans lost 117,000 men (9). Mawdsley, who has also presented these figures, revealed that “German losses on the Russian front in the last quarter of 1941, despite the onset of winter and the drama of the drive on Moscow, were lower than those in the summer… These fourth-quarter figures represented a ratio of losses between the Russians and Germans of as much as 8:1”. (10)

In the first six months of 1942, a similar ratio prevailed in the war. From January to June 1942 the Germans inflicted 1.4 million casualties on the Soviets, as opposed to 188,000 casualties for the invaders (11). The great portion of blame, for the disparity in these figures, should not be attached to the frontline Russian (or Soviet) soldier. In both world wars, he proved overall to be a tough and resourceful fighter, capable of fanatical resistance. The responsibility lies ultimately with the state’s long-time ruler, Joseph Stalin, who had taken it upon himself to purge the Soviet military’s officer ranks beginning in May 1937; just when the spectre of war was about to envelop Europe once more, so the timing could hardly have been worse.

As the distinguished Soviet diplomat Andrei Gromyko recalled in his autobiography, Marshal Zhukov spoke bitterly after the war of “the enormous damage Stalin had inflicted on the country by his massacre of the top echelons of the army command” (12). Around 20,000 Soviet military officers and commissars had been arrested “and the greater part were executed”, Mawdsley wrote (13). This is a smaller number than purported in Western propaganda, but it was still significant, and the Red Army’s senior commanders were of course disproportionately targeted.

The worst of the Red Army purges occurred between 1937-1938, but the arrests and executions continued right up to the eve of war with Nazi Germany on 22 June 1941, notably targeting the Soviet Air Force command (14). The result was that the Soviet military, despite lavish spending on armaments for years, was a weak instrument by the time the Germans attacked. The Red Army was desperately short of experienced and capable commanders, when they were needed most.

Mawdsley wrote of those that had been purged,

“These men possessed the fullest professional, educational and operational experience the Red Army had accumulated. They had presided over an extraordinary modernization of doctrine and matériel of the early 1930s. Despite professional and personal rivalries among themselves, these leaders had formed a fairly cohesive command structure. The paradox is that this was precisely why Stalin mistrusted them”. (15)

Had the officers in question been organising a plot to overthrow Stalin, one could at least understand the latter’s actions. Yet a coup does not seem to have been on the horizon. According to Zhukov, who knew some of the Soviet officers in question, those who had been liquidated were “innocent victims” (16). In addition, Zhukov wrote in his memoirs of “unfounded arrests in the armed forces” which were “in contravention of socialist legality” and this had “affected the development of our armed forces and their combat preparedness”. (17)

Of those who remained in the Red Army’s command structure, their initiative and ability to make independent decisions had been paralysed. It was an inevitable byproduct of the psychological damage inflicted by the purges also. Mawdsley realised “a mental state was imposed which was the very opposite of the German ‘mission-oriented command system’”, which encouraged and rewarded independent thinking. (18)

The Red Army purges convinced possible allies and enemies that the Soviet military was in disarray. Exploiting the circumstances, German agencies forwarded details of the purges to British and French intelligence (19). Hitler’s own opinion that the Red Army was of poor quality strengthened in the winter of 1939-40, when he learned of the Soviet forces struggling to overcome a much smaller Finnish Army. The purges were a factor too behind the British and French refusal to sign a pact with Russia, in the late 1930s, which would have aligned those three states against Germany, as during the First World War.

The British and French leaders were, by and large, intensely anti-Bolshevik which can’t be forgotten. The purges served as an excuse to increase their prejudices against communist Russia. Relating to the Anglo-French military hierarchy, Leopold Trepper, a leading former Red Army intelligence agent wrote in his memoirs, “I am inclined to think that the French and English chiefs of staff were less than impatient to seal a military alliance with the Soviet Union, because the weakness of the Soviet Army had become clear to them”. (20)

This weakness was acknowledged not only by Zhukov but other top level Soviet military figures, like Marshal Kliment Voroshilov. In early October 1941 Voroshilov, the pre-war commander of the Red Army, told the Communist International (Comintern) leader Georgi Dimitrov that the situation at the front is “awful”. Voroshilov went on that “our organisation is weaker than theirs. Our commanding officers are less well trained. The Germans succeed usually because of their better organisation and clever tricks”. (21)

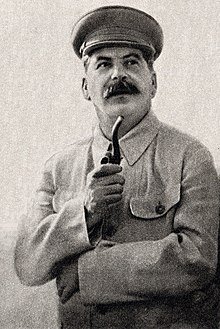

Image below: Joseph Stalin (Licensed under the public domain)

The Soviet cause had been hindered too, by Stalin’s refusal to believe the intelligence reports warning of an imminent German invasion. The most plausible intelligence material regarding Nazi intentions came from Soviet agents, such as Trepper, Richard Sorge and Harro Schulze-Boysen, all of whom informed the Kremlin about Operation Barbarossa.

The reports converged and showed an obvious pattern, peaking in intensity and accuracy in the first 3 weeks of June 1941; but Stalin continued to discount the intelligence information sent to him personally. A few days before the Germans invaded, in mid-June 1941 Stalin told Zhukov, “I believe that Hitler will not risk creating a second front for himself by attacking the Soviet Union” (22). Also revealing is that when Stalin was awakened and informed of heavy German shelling along the Nazi-Soviet border, he said, “Hitler surely doesn’t know about it”. (23)

The Germans achieved a major element of surprise in their invasion, advancing quicker and inflicting more damage than they would otherwise have been able to. When the Axis forces swarmed over the frontiers, many Soviet troops were either on leave, separated from their artillery, overrun and taken prisoner before they could mount an effective defence. Within a week of the invasion, the Soviets had suffered about 600,000 casualties and the Germans had advanced more than halfway to Moscow.

Three and a half weeks into the attack, by 16 July 1941 the Wehrmacht was more than two-thirds of the way to the Soviet capital, having reached the city of Smolensk in western Russia, 230 miles from Moscow as the crow flies. Robert Service, an historian of Russian history, wrote how “A military calamity had occurred on a scale unprecedented in the wars of the twentieth century” (24). It is conventionally believed, for an offensive to succeed decisively, that the attackers should outnumber the defenders by 3 to 1 (25). This was certainly not the case in the Nazi-Soviet War, and it offers one crucial reason as to why the German invasion would fail.

The Germans and their Axis allies (mainly Romanians and Finns at first) attacked the USSR with 3,767,000 men; the Soviet military’s personnel strength on the eve of war, taking in the whole of the USSR, amounted to 5,373,000, of which 4,261,000 belonged to the ground forces, the remainder to the air force and navy (26). By the end of 1941, the Germans had virtually destroyed the original 5 million strong Soviet military. However, there was a reserve force to be called upon of 14 million Soviet citizens who, it must be said, had only basic military training; among the Red Army reservists were a million women, about half of them present on the frontline in a variety of roles (27). The Soviet Union’s population was more than 190 million in 1941, not far away from being double that of the Reich’s population.

The Soviet military possessed much larger numbers of tanks, airplanes and artillery than the Germans and their allies. Stalin must be given due credit here, because he had overseen the USSR’s armament drive since the early 1930s. Spending on the Soviet defence budget increased by 340% in absolute terms from 1932 to 1937, and expenditure on arms doubled again between 1937 and 1940. (28)

Directly involved in the fighting at the war’s outset were 11,000 Soviet tanks, in opposition to 4,000 Axis tanks, 9,100 Soviet combat aircraft compared to 4,400 Axis combat aircraft, and 19,800 Soviet artillery pieces as opposed to 7,200 Axis artillery pieces (29). The German-led armies, on paper, should have been at a clear disadvantage from the beginning.

The size of the USSR’s landmass was a further critical factor in Barbarossa’s failure. Russia by itself is easily the world’s largest country, but the Germans assailed other states like the Ukraine (Europe’s second biggest country today), and they also entered Belarus and the Baltic nations. Had the Red Army been concentrated in an area the size of France, the Wehrmacht would most probably have been victorious within a reasonably short space of time.

The farther that the Germans advanced into the western Soviet Union, the broader the land became, a vast expanse opening up in front of them. This was increasingly the case when an invading force attacked across the whole front. While the Germans could do nothing about the terrain’s breadth, they could have shortened the distance by directing their 3 Army Groups in a straight thrust towards Moscow, the USSR’s transportation and communications hub.

By the second half of August 1941, forward units of German Army Group Centre were just 185 miles from Moscow (30). The Wehrmacht’s real weakness was its high command’s strategic shortcomings, compounded by Hitler’s interference, most fatefully his directive of 21 August 1941 – when the Nazi leader postponed the advance on Moscow in order to capture Leningrad, Kiev and the Crimea among other goals. (31)

This directive, a pivotal turning point in the entire war, resulted in a 6 week delay in the approach towards Moscow. It meant in the end that the capital went uncaptured by the Nazis, and the Soviet Union as a result would survive the war, though a long and difficult struggle lay ahead.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree and he writes primarily on foreign affairs and historical subjects. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Notes

1 Evan Mawdsley, Thunder in the East: The Nazi-Soviet War, 1941-1945 (Hodder Arnold, 23 Feb. 2007) p. 147

2 Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chronology and Index of the Second World War, 1938-1945 (Meckler Books, 1990) p. 278

3 Donald J. Goodspeed, The German Wars (Random House Value Publishing, 3 April 1985) p. 405

4 Chris Bellamy, Absolute War: Soviet Russia in the Second World War (Pan; Main Market edition, 21 Aug. 2009) p. 6

5 Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939-1953 (Yale University Press; 1st Edition, 14 Nov. 2006) p. 10

6 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 147

7 Ibid., p. 127

8 Ibid., pp. 85-86

9 Ibid., pp. 116-117

10 Ibid., p. 117

11 Ibid., p. 147

12 Andrei Gromyko, Memories: From Stalin to Gorbachev (Arrow Books Limited, 1 Jan. 1989) p. 216

13 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, pp. 20-21

14 Ibid., p. 21

15 Ibid.

16 Gromyko, Memories: From Stalin to Gorbachev, p. 216

17 Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov (Icon Books, 2 May 2013) p. 46

18 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 21

19 Leopold Trepper, The Great Game: Memoirs of a Master Spy (Michael Joseph Ltd; First Edition, 1 May 1977) p. 67

20 Ibid., pp. 67-68

21 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 19

22 Ibid., p. 18

23 Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (Pan; Reprints edition, 16 April 2010) p. 410

24 Ibid., p. 411

25 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 19

26 Ibid., pp. 19 & 30

27 Roberts, Stalin’s Wars, p. 163

28 Roberts, Stalin’s General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov, p. 43

29 Mawdsley, Thunder in the East, p. 19

30 Samuel W. Mitcham Jr., Gene Mueller, Hitler’s Commanders: Officers of the Wehrmacht, the Luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine and the Waffen-SS (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2nd Edition, 15 Oct. 2012) p. 37

31 Goodspeed, The German Wars, p. 396

Featured image: The center of Stalingrad after liberation, 2 February 1943 (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)