NATO’s Law of the Jungle in Libya

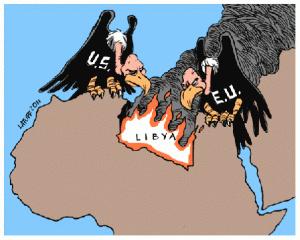

The murder of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi was widely hailed in the West as a just outcome. But it involved powerful nations making up the rules as they went along, the law of the jungle disguised as international justice, observes Peter Dyer.

If there is one thing the “humanitarian” intervention in Libya has convincingly demonstrated it is this: the only real international law is the law of brute force.

The Libyan dust now appears to be settling. Colonel Muammar Gaddafi has been summarily executed and the NATO intervention has officially ended. The dominant narrative is that the intervention was a timely, legal and morally justified action that fulfilled the primary purpose of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973, passed on March 17: the protection of civilians in Libya’s civil war.

But there is an alternative narrative: three major powers invoked the United Nations Charter in order to violate it. The United States, the United Kingdom and France engineered a “humanitarian” intervention that was in reality an unprovoked act of war against a sovereign state.

The intervention resulted not only in illegal regime change — a violation of Article 2(4) of the UN Charter — but in the extrajudicial assassination of its head of state.

The primary stated purpose of UNSC Res. 1973 was indeed the protection of civilians – through an immediate ceasefire – but that was not how the resolution was implemented.

Paragraph 1 states: “[The Security Council] Demands the immediate establishment of a cease-fire and a complete end to violence and all attacks against, and abuses of, civilians.”

Instead, NATO intervened on the side of the rebellion, violating Res. 1973. Instead of preventing civilian casualties by stopping the civil war, NATO extended the conflict by another seven months, ignoring the willingness of the Gaddafi government to accept a ceasefire and thus increasing civilian casualties.

In doing so, NATO degraded further what remains of the rule of international law, destroyed a secular Arab government and may have facilitated its eventual replacement by an Islamist state.

On April 10, three weeks after the NATO bombing began, Libya accepted a proposal by the African Union for an immediate ceasefire; the unhindered delivery of humanitarian aid; protection of foreign nationals; a dialogue between the government and rebels on a political settlement, and the suspension of NATO air strikes. The next day the Libyan rebels rejected this offer.

The rebels and the three NATO powers leading the invasion – France, UK and the U.S. – were not focused on any of this. Despite their mandate to “protect civilians,” regime change was their actual goal.

The “Big Three” made their intentions clear in a joint statement three days after the rebels rebuffed the African Union by saying: “Gaddafi must go and go for good.”

On May 10 at the United Nations, the alternative narrative of Big Power abuse was touched upon as several states, including three Security Council members, belatedly warned against these developments.

Brazil’s Ambassador to the UN, Maria Luiza Ribeiro Viotti, said: “We must take the greatest care to ensure that our actions douse the flames of conflict instead of stoking them.”

Though South Africa had voted in favor of Res. 1973, Ambassador Baso Sangqu said: “United Nations peacekeeping operations should never be seen to be siding with one party to a conflict, as that would undermine the integrity of United Nations efforts. … (W)e are concerned that the implementation of these resolutions appears to go beyond their letter and spirit. …

“International actors and external organizations … should … refrain from advancing political agendas that go beyond the protection of civilian mandates, including regime change.”

Chinese Ambassador Li Baodong was more blunt: “There must be no attempt at regime change or involvement in civil war by any party under the guise of protecting civilians.”

Nicaraguan Ambassador Mrs. Rubiales de Chamorro was passionate: “The Security Council must explain to us, particularly in the light of resolution 1973 (2011), how civilians are to be protected from shelling. We ought to be told — because we have the right to know — how many civilians have perished in the name of this alleged protection of civilians.

“We need to be told who is going to protect the civilians from their supposed protectors. Someone needs to explain to us how, in applying the protection of civilians, the assassination of a head of State of a sovereign country is planned. We must be told how the bombing death of innocent children contributes to the protection of civilians.”

Dr. Lawrence Emeka Modeme, a lecturer in International Law at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK, made a strong case that the Security Council by itself had no authority to intervene in Libya.

In “The Libyan Humanitarian Intervention: Is it Lawful in International Law?” he pointed out that UN Charter Chapter VII authorizes the Security Council to approve military intervention in a country only as a response to a breach of, or threat to, international security. The Libyan conflict was internal – there was no military threat to any other country.

Though a humanitarian intervention may have been called for, Dr. Modeme argued, the General Assembly rather than the Security Council was the legitimate organ to authorize it. Dr. Modeme cited UN Charter Articles 10 and 14 as well as UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251, which established the Human Rights Council.

He contended that “it should be the prerogative of the Human Rights Council to determine whether the threshold for humanitarian intervention has been reached and to recommend to the General Assembly whether collective humanitarian intervention should be undertaken. The General Assembly would then vote to authorize any necessary action.”

This, he argued, would entail removing the disproportionate power wielded by the five veto-bearing permanent members of the Security Council.

Majority decisions in the Human Rights Council and in the General Assembly would make “the process more transparent, more consensual, and less open to abuse. … Security Council interventions, due largely to the influence of the veto-wielding members, is largely inconsistent, political and influenced by self-interest. This inconsistent and selective use of [UN Charter] Chapter VII powers has observably irked many states and has undermined the integrity of humanitarian interventions.”

In July 2003, after the United States had invaded and overthrown the government of Iraq, a country that was not presenting a threat to international peace, American international law expert Dr. Thomas M. Franck wrote: “The law based system is once again being dismantled. In its place we are offered a model that makes global security wholly dependent on the supreme power and discretion of the United States and frees the sole superpower from all restraints of international law and the encumbrances of institutionalized multilateral diplomacy.” [American Journal of International Law, July 2003, Vol. 97 p 608]

At the time this perspective, too, represented an alternative narrative to the dominant storyline – at least in the United States.

Sadly, though, Dr Franck’s words proved prophetic. Less than eight years later, the U.S., acting through its proxy NATO, invaded another Arab country presenting no threat to international peace.

As U.S. Rep. Dennis Kucinich, D-Ohio, said: “NATO’s top commanders may have acted under color of international law but they are not exempt from international law.

“If members of the Gaddafi Regime are to be held accountable, NATO’s top commanders must also be held accountable through the International Criminal Court for all civilian deaths resulting from bombing. Otherwise we will have witnessed the triumph of a new international gangsterism.”

Peter Dyer is a freelance journalist who moved with his wife from California to New Zealand in 2004. He can be reached at [email protected] .