Monsanto Roundup & Dicamba Trial Tracker

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

This blog by Carey Gillam is updated regularly with news and tips about the lawsuits involving Monsanto’s glyphosate-based Roundup weed killer products.

October 25, 2021

Stephens trial drags on, toxicologist testifies about studies of herbicide and cancer risk

A scientist testified Monday that a California woman’s regular use of Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide “vastly” exceeded the exposure scientific research shows more than doubles the risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

William Sawyer, a toxicologist and expert witness for plaintiff Donnetta Stephens in her lawsuit against Monsanto, cited scientific research that links use of Monsanto’s glyphosate-based herbicides, including Roundup, to cancer and specifically to NHL. Sawyer has testified in prior Roundup cancer trials, including a 2019 trial that resulted in a jury verdict of more than $2 billion for a husband-and-wife who both suffered from NHL.

The Stephens v. Monsanto trial has been underway for roughly three months, starting in late July. The proceedings have been handled via Zoom, and multiple technical problems have at time hindered the delivery of testimony and sharing of evidence with jury members.

Jurors have heard from Stephens, her son, various cancer experts and from some of Monsanto’s top scientists, including longtime Monsanto toxicologist Donna Farmer. Farmer now works for Bayer AG, the German pharmaceutical company that bought Monsanto in 2018.

“Perpetual” pain

Stephens’ trial is a “preference” case, meaning her case was expedited after her lawyers informed the courtthat Stephens was “in a perpetual state of pain” and losing cognition and memory.

The case is being tried in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California under the oversight of Judge Gilbert Ochoa. Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Juries in the first three trials found in favor of the plaintiffs, agreeing with claims that Monsanto’s glyphosate-based weed killers, such as Roundup, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Monsanto spent decades covering up the risks, and failing to warn users.

Monsanto won a recent trial involving a mother who claimed her son developed NHL because of exposure he experienced while she sprayed the weed killer.

More trouble for Bayer

Angry investors can proceed with litigation against Bayer over allegations that the company made misleading statements about its $63 billion 2018 acquisition of Monsanto, and of the extent of concerns about the company’s herbicide products.

A federal judge ruled last week that a class action led by a group of pension funds can proceed with their claims that Bayer proceeded with its purchase of Monsanto despite analyst warnings and an awareness that acquiring Monsanto brought significant risks, and assuring investors Bayer management had fully assessed those risks.

Bayer has settled several cases that were scheduled to go to trial over the last two years. And in 2020, the company said it would pay roughly $11 billion to settle a majority of the more than 100,000 existing Roundup cancer claims. The company recently said it was setting aside another $4.5 billion toward Roundup litigation liability.

Bayer also announced it would stop selling Roundup, and other herbicides made with the active ingredient glyphosate, to U.S. consumers by 2023. But the company continues to sell the products for use by farmers and commercial applicators.

October 6, 2021

Bayer wins Roundup trial; plaintiff fails to prove exposure caused child’s disease

The former Monsanto Co., now owned by Bayer AG, notched its first win in the mass tort U.S. Roundup litigation on Tuesday, defeating at trial a mother who alleged her use of Roundup exposed her child to the pesticide and caused him to develop cancer.

Ezra Clark was born in May 2011 and diagnosed in 2016 with Burkitt’s lymphoma, a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) that has a high tendency to spread to the central nervous system, and can also involve the liver, spleen and bone marrow, according to the court filings. Ezra’s mother, Destiny Clark, is the plaintiff in the case, which was heard in Los Angeles County Superior Court. A different Roundup trial is underway in San Bernardino County Superior Court.

Ezra Clark was “directly exposed” to Roundup many times as he accompanied his mother while she sprayed Roundup to kill weeds around the property where the family lived, according to court documents. Ezra has autism and his mother said it calmed him to play outdoors while she worked in the yard, which meant he often played in areas freshly sprayed with Roundup, according to the court filings.

Fletch Trammell, lead attorney for Clark, said his case was subject to a bifurcation order that organized the case into two phases. In the first phase he was limited to presenting evidence that focused on the child’s personal exposure to Roundup and whether or not it could have been enough to have contributed to his disease. The case would have proceeded to a second phase had the plaintiff won the first phase, but the loss in the first phases ends the trial.

“This was nothing like any of the other three trials,” Trammell said.

The jury was asked to address one key question in the first phase: Whether or not the child’s exposure to Roundup was a “substantial factor” in his development of Burkitt’s lymphoma.

In a 9 to 3 decision, the jury found that it was not.

Trammell said the jury decision was because the jury doubted the child’s exposure to Roundup could have been enough to cause cancer. The decision did not address the larger question of the alleged carcinogenicity of Roundup overall, he said.

But Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018 as the first Roundup trial was getting underway, said the jury’s decision was in line with scientific research showing glyphosate, the main ingredient in Roundup, is safe and does not cause cancer.

“The jury carefully considered the science applicable to this case and determined that Roundup was not the cause of his illness,” the company said in a statement.

80 hours

During the trial, Trammel presented evidence indicating Ezra was exposed to Roundup for about 80 cumulative hours over the years his mother sprayed with him at her side. He paired that with research showing there could ben an increased risk of NHL associated with repeated spraying of glyphosate herbicides, such as Roundup. And he noted language on Roundup labels in Canada that advise users to wear protective gloves and avoid getting the chemical on bare skin.

“The studies… they show that Roundup does three different things when it gets to your

lymphocyte cells… It can kill cells, which is bad enough; but it also causes the exact DNA damage

that results in Burkitt’s lymphoma; it also, in a variety of ways, devastates your body’s ability to

repair DNA damage,” Trammell told jurors in his closing argument.

Trammell also sought to counter problems with deposition testimony given by Destiny Clark. Trammell said the mother also has suffered from cancer, a cervical cancer that metastasized to her brain. The illness and treatments she has undergone made it difficult for her to recall details and she “made a lot of mistakes” in the deposition she gave to Monsanto’s attorneys, Trammell told jurors. But she was very clear, he told jurors, on recalling her use of Roundup nearly “every weekend” when Ezra was young.

Monsanto attorney Brian Stekloff told jurors that Ezra’s exposure was in doubt. He told jurors that while they might have sympathy for the family, they could not ignore inconsistencies in Destiny Clark’s testimony about how often her son was exposed, and could not ignore statements by other family members that they did not see her spraying around Ezra.

“And there is an old adage or old saying, and it goes like this: The truth is simple because there’s nothing to remember,” Stekloff told jurors. “When you tell the truth, you don’t mix up the facts. It’s when it didn’t happen that you can’t remember what you said the first time and the next time, and the next time, and the next time. And the inconsistencies start piling up and piling up, and the explanations start coming and piling up and piling up. And that’s what you have seen here in this trial.”

Stekloff told jurors the evidence did not support a finding that exposure to Roundup was a substantial factor in causing his cancer.

“This is not a popularity contest. This is not a referendum on Monsanto. It’s not even a referendum on Roundup,” he said in his closing argument. “Roundup did not cause Ezra Clark’s Burkitt’s lymphoma.”

Clark is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts in 2015 classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to NHL.

Monsanto lost each of the three previous trials, after lawyers for the plaintiffs presented jurors with multiple scientific studies finding potential health risks with glyphosate and Roundup The plaintiffs lawyers also used internal Monsanto documents as evidence, arguing the so-called “Monsanto Papers” showed intentional efforts by the company to manipulate regulators and control scientific research.

The jury in the last trial ordered $2 billion in damages though the award was later shaved to $87 million.

Bayer has maintained that there is no cancer risk with the glyphosate herbicides it inherited from Monsanto, but it has agreed to pay close to $14 billion to try to settle the litigation and said it will remove glyphosate products from the U.S. consumer market by 2023. The company will continue to sell the herbicides to farmers and other commercial users.

Mike Miller, who heads the Virginia law firm that won two of the three previously held Roundup trials, i but who was not involved in the Clark case, said the verdict does not change anything about the litigation, nor Bayer’s liability.

“Nothing about that verdict change the fact: Roundup causes cancer,” he said.

October 5, 2021

Monsanto scientist tells jurors company’s side of Roundup cancer controversy

A senior scientist at the former Monsanto Co. on Tuesday told jurors in a California trial that regulators around the world support the company’s position that its glyphosate-based herbicides, such as the popular Roundup brand, are safe for users.

Donna Farmer, who worked as a toxicologist at Monsanto for more than two decades and now works at Monsanto owner Bayer AG, spent long hours testifying in the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto. Farmer has been a key witness in the Stephens case and was quizzed intently for days by lawyers for Stephens before Monsanto’s lawyers took up the questioning.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts in 2015 classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s Roundup and other herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The Stephens case is the fourth Roundup cancer lawsuit to go to trial and the first since 2019. Stephens suffers from non-Hodgkin lymphoma she blames on her use of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years.

A chance to explain

Monsanto lawyer Monsanto lawyer Manuel Cachan questioned Farmer about several issues that were raised earlier by plaintiffs’ attorneys, telling Farmer it was her chance to explain details about several matters that Stephens’ lawyers had presented as evidence of Monsanto wrong-doing.

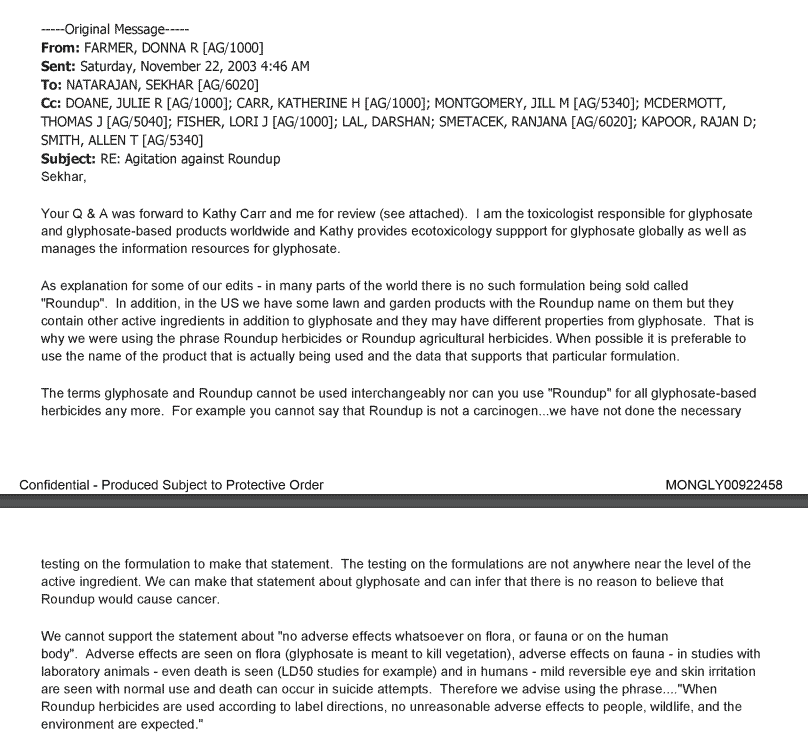

One such issue involved comments Farmer wrote in a 2003 email to colleagues about the importance of distinguishing between the chemical glyphosate and the Roundup formulation, which is made with glyphosate as the active ingredient.

In the email, Farmer wrote “The terms glyphosate and Roundup cannot be used interchangeably nor can you use “Roundup” for all glyphosate-based herbicides any more. For example you cannot say that Roundup is not a carcinogen… we have not done the necessary testing on the formulation to make that statement. The testing on the formulations are not anywhere near the level of the active ingredient.”

Plaintiffs’ lawyers have pointed to that language as part of a broad argument disputing Monsanto’s contention that thorough testing of Roundup has demonstrated it does not cause cancer.

In testimony Tuesday, Farmer said that she merely was trying to be “very precise” when explaining to colleagues the distinctions between products. She was not indicating in the email that there was any question about whether or not Roundup might cause cancer, Farmer testified.

She pointed out that in that internal email she also wrote “there is no reason to believe that Roundup would cause cancer.”

And though it was true at that time that Monsanto had not conducted extensive carcinogenicity testing on Roundup formulations, that changed over time, Farmer testified.

“I think we’ve got a lot more studies on Roundup than we had, and so I think we have a lot more information about the Roundup formulations that still supports the conclusions and safety about the formulation,” Farmer told the jury.

A regulatory pass

At another point in the questioning by Monsanto’s lawyer, Farmer told jurors that regulators had never required the company to conduct animal carcinogenicity testing on Roundup. She said not only had the U.S. EPA not demanded such testing, but regulators in Canada, Europe, Australia and Japan had similarly not required any such animal testing on Roundup products.

She also told jurors that while it was true that Roundup products contain formaldehyde, it was a “very, very small amount” and posed no danger to human health. Regulators agreed there was no reason for concern, Farmer testified.

“We produce formaldehyde every day in our bodies,” said Farmer. “Small amounts of formaldehyde like in the formulations at those low levels do not present a health hazard to humans.”

Farmer’s testimony sought to rebut other points of evidence raised by Stephens’ lawyers, seeking to cast Monsanto as a responsible, science-based organization that has been the innocent target of activist-driven misinformation. Plaintiffs’ lawyers have twisted internal conversations seen in emails and other communications to confuse and mislead jurors, according to arguments by Monsanto attorneys.

Monsanto lost each of the three previous trials, after lawyers for the plaintiffs presented jurors with multiple scientific studies finding potential health risks with glyphosate and Roundup The plaintiffs lawyers also used internal Monsanto documents as evidence, arguing they showed intentional efforts by the company to manipulate regulators and control scientific research.

Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, has settled other cases that had been scheduled to go to trial. And in 2020, the company said it would pay roughly $11 billion to settle about 100,000 existing Roundup cancer claims. Bayer also recently said it would set aside another $4.5 billion toward Roundup litigation liability.

To try to quell future litigation, Bayer said it would stop selling Roundup, and other herbicides made with the active ingredient glyphosate, to U.S. consumers by 2023. But the company continues to sell the products for use by farmers and commercial applicators.

September 28, 2021

Monsanto scientist defends Roundup safety in California trial

A senior scientist at the former Monsanto Co. told jurors in a California trial that the company’s Roundup herbicide is so safe that the scientist uses it regularly at her home, and suggests friends also use the weed killing product.

Donna Farmer, who worked as a toxicologist at Monsanto for more than two decades and now works at Monsanto owner Bayer AG, spent long hours testifying Monday and on multiple days last week in the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto. The Stephens case is the fourth Roundup cancer lawsuit to go to trial and the first since 2019. Stephens suffers from non-Hodgkin lymphoma she blames on her use of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts in 2015 classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Monsanto lost each of the three previous trials, after lawyers for the plaintiffs presented jurors with multiple scientific studies finding potential health risks with glyphosate and Roundup The plaintiffs lawyers also used internal Monsanto documents as evidence, arguing the so-called “Monsanto Papers” showed intentional efforts by the company to manipulate regulators and control scientific research.

The jury in the last trial ordered $2 billion in damages though the award was later shaved to $87 million.

Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, insists there is no cancer risk with its glyphosate herbicides, but it has agreed to pay close to $14 billion to try to settle the litigation and said it will remove glyphosate products from the U.S. consumer market by 2023. The company will continue to sell the herbicides to farmers and other commercial users.

Combative exchanges

In testimony delivered under cross-examination by Stephens’ lawyer William Shapiro, Farmer was combative, going beyond answering the yes or no questions Shapiro posed to her in an effort to “explain” the context she said Shapiro was misrepresenting.

Shapiro quizzed Farmer about emails and documents dating back to the late 1990s that Shapiro presented as evidence that Farmer and other company scientists engaged in misconduct, including ghostwriting scientific papers to fraudulently assert the safety of its glyphosate-based herbicides and buried information that found cancer risk with the products.

On Monday, Monsanto lawyer Manuel Cachan questioned Farmer about many of the same pieces of evidence focused on by Shapiro, but cast the emails and other evidence as innocent exchanges that bear no signs of deceit or misconduct.

Under Cachan’s questioning, Farmer said that based on the science that she is familiar with, she does not believe glyphosate causes cancer, and is confident that Roundup is safe to use. She said that she is so certain of the safety of Roundup that she has used it around her yard for about 25 years. She does not wear gloves or special protective gear when spraying, she testified. Farmer said she has no worries about recommending the product to family members and friends.

Farmer said the phase-out for consumers is not due to any safety concerns and is being removed from consumer markets simply “because of the litigation and the lawsuits.” Farmer said she does not think the product should be withdrawn.

“The product is in my opinion – and not just my opinion but regulators around the world – the product is safe and is not a carcinogen,” Farmer testified.

Even after Bayer stops selling Roundup to consumers in 2023, Farmer said she plans to keep using it.

“It has a good shelf life so I’ll probably buy some extra bottles,” she said. “You can go to dealerships in farm country, you can buy some of the products there.”

Monsanto has been persecuted by an anti-pesticide movement, according to Farmer.

“There are a lot of people who don’t like pesticides. They don’t like glyphosate and quite frankly don’t like Monsanto. There are a lot of people who make allegations and spread misinformation about the safety of our products,” Farmer testified.

Beyond Pesticides

At one point in her testimony, Farmer weighed in on a nonprofit group and Monsanto critic called Beyond Pesticides, telling jurors that Beyond Pesticides was not a scientific group but rather an activist group that was “misrepresenting the science” about synthetic pesticides such as glyphosate.

“Their mission is to stop the use of synthetic pesticides and so what they publish is misinformation, inaccurate information about pesticides,” she testified.

Monsanto’s lawyer asked her to address a 2008 internal Monsanto email regarding a press release issued by Beyond Pesticides. The press release by the nonprofit group shared a research study that found glyphosate exposure could increase a person’s risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The group advised people should embrace organic agriculture and use “non-toxic land care” on residential lawns.

In the email, Farmer had written to colleagues: “We have been aware of this paper for awhile and knew it would only be a matter of time before the activists picked it up.” Mentioning the Beyond Pesticides line about embracing organic agriculture, Farmer had written: How do we combat this?”

Under questioning from Monsanto’s lawyer, Farmer explained that she was not indicating Monsanto should try to combat the scientific research but was addressing only the Beyond Pesticide advice about avoiding pesticide use.

The Stephens trial started as an in-person proceeding but was changed to a Zoom trial due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19, and has been plagued by repeated “technical problems” ever since the change. Several times jurors and/or a witness have lost their audio and/or video connections to the trial.

Judge Gilbert Ochoa of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California, is overseeing the proceedings.

The trial does not resume until Monday Oct. 4 because of scheduling conflicts for some of the trial participants.

September 22, 2021

Cancer patient lawyer spars with Monsanto scientist in California Roundup trial

A lawyer for a woman claiming her use of Roundup herbicide caused her to develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma sparred with a longtime Monsanto scientist in court on Wednesday, forcing the scientist to address numerous internal corporate documents about research showing Monsanto weed killers could be genotoxic and lead to cancer.

The testimony by former Monsanto scientist Donna Farmer marked her second day on the stand and came several weeks into the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto, the fourth Roundup trial in the United States, and the first since 2019. Juries in three prior trials all found in favor of plaintiffs who, like Stephens, alleged they developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma due to their use of Roundup or other Monsanto herbicides made with the chemical glyphosate. Thousands of people have filed similar claims.

Bayer AG, which bought Monsanto in 2018, has earmarked more than $14 billion to try to settle all of the U.S. Roundup litigation, but many plaintiffs have refused to settle, and cases continue to go to trial.

A “genotox hole”

In hours of contentious back-and-forth, interrupted repeatedly by objections from a Monsanto attorney, Stephens’ lawyer William Shapiro quizzed Monsanto toxicologist Donna Farmer about emails and documents dating back to the late 1990s that focused on research – and the company’s handling of that research – into whether or not the company’s herbicide products could cause cancer.

In one line of questioning, Shapiro asked Farmer about emails in which she and other company scientists discussed the company’s response to outside research that concluded the company’s glyphosate-based herbicides were genotoxic, meaning they damaged human DNA. Genotoxicity is an indicator that a chemical or other substance may cause cancer.

Shapiro focused during one series of questions on work done by a scientist named James Parry, who Monsanto hired as a consultant in the 1990s to weigh in on the genotoxicity concerns about Roundup being raised at the time by outside scientists. Parry’s report agreed there appeared to be “potential genotoxic activity” with glyphosate, and recommended that Monsanto do additional studies on its products.

In an internal Monsanto email dating from September 1999 written to Farmer and other company scientists, a Monsanto scientist named William Heydens said this about Parry’s report: “let’s step back and look at what we are really trying to achieve here. We want to find/develop someone who is comfortable with the genetox profile of glyphosate/Roundup and can be influential with regulators and Scientific Outreach operations when genetox issues arise. My read is that Parry is not currently such a person, and it would take quite some time and $$$/studies to get him there. We simply aren’t going to do the studies Parry suggests.”

In a separate email revealed through the litigation, Farmer wrote that Parry’s report put the company into a “genotox hole” and she mentioned a suggestion by a colleague that the company should “drop” Parry.

Farmer testified that her mention of a “genotox hole” referred to problems with “communication” not about any cancer risk. She also said that she and other Monsanto scientists did not have concerns with the safety of glyphosate or Roundup, but did have concerns about how to respond to paper and research by outside scientists raising such concerns.

Shapiro pressed Farmer on her reaction to Parry’s finding: “You thought it would be okay on behalf of Monsanto to receive information as you did from Dr. Parry that this Roundup product was genotoxic or could be, you thought it would be okay to go ahead and continue to sell the product, correct?”

Farmer replied: “We didn’t agree with Professor Parry’s conclusions at the time that it may be, could be, capable of being genotoxic. We had other evidence…. We had regulators who had agreed with our studies and conclusions that it was not genotoxic.”

Her answer was interrupted as Shapiro objected, saying he was asking a yes or no question and Farmer’s attempt to respond beyond that should be stricken. The judge agreed and struck part of the response.

Continuing his questioning, Shapiro asked: “Well that didn’t work out to have Dr. Parry be the spokesperson for Monsanto, did it Dr. Farmer?

“I would disagree with you because there is still a lot more to this Professor Parry, working with him, and I’d be happy to…” Farmer replied before being cut off by another Shapiro objection and the judge’s striking of everything following the first five words.

A similar pattern played out throughout Farmer’s testimony as Stephens’ lawyer objected to Farmer’s attempts to provide extended answers to multiple questions posed, and Monsanto’s lawyer Manuel Cachan objecting repeatedly to Shapiro’s questions as “argumentative.”

Ghostwriting and “FTO”

Shapiro asked Farmer to address multiple issues expressed in the internal corporate emails, including one series in which Monsanto scientists discussed ghostwriting scientific papers, including a very prominent paper published in the year 2000 that asserted there were no human health concerns with glyphosate or Roundup.

Shapiro additionally asked Farmer to address a strategy Monsanto referred to in emails as “Freedom to Operate” or “FTO”. Plaintiffs’ lawyers have presented FTO as Monsanto’s strategy of doing whatever it took to lessen or eliminate restrictions on its products.

And he asked her about Monsanto emails expressing concerns about research into dermal absorption rates – how fast its herbicide might absorb into human skin.

Farmer said multiple times that information was not being presented in the correct context, and she would be happy to provide detailed explanations for all of the issues raised by Shapiro, but was told by the judge she would need to wait until questioning by Monsanto’s lawyers to do so.

Zoom trial

The Stephens trial is taking place under the oversight of Judge Gilbert Ochoa of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California. The trial is being held via Zoom due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19, and numerous technical difficulties have plagued the proceedings. Testimony has been halted multiple times because jurors have lost connections or had other problems that inhibited their ability to hear and view the trial testimony.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The three prior trials were all lengthy, in-person proceedings loaded with weeks of highly technical testimony about scientific data, regulatory matters and documents detailing internal Monsanto communications.

September 20, 2021

Monsanto lawyer cross-examines cancer patient over her claims Roundup caused her disease

A California woman suing Monsanto over allegations that her use of Roundup weed killer caused her to develop cancer testified Monday that she had a hard time remembering many details about the extent of her use of the pesticide, struggling to answer several questions posed by a Monsanto attorney.

In cross examination, Monsanto attorney Bart Williams pressed plaintiff Donnetta Stephens on how much and when she had used the company’s popular herbicide before she was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 2017. Peppering Stephens with questions about changes in information she provided in depositions and interrogatories, the company’s lawyer sought to cast doubt on the span and volume of her actual use and exposure.

In testimony last week, Stephens’ son David Stephens recalled his mother’s frequent use of Roundup and her tendency to wear sleeveless shirts and shorts when outside spraying the weed killer. He described recalling her use when he was a child and seeing that use continuing when he was an adult.

But in Monday’s testimony, Williams sought to undermine Donnetta Stephens credibility, implying that her son and husband were the architects of many of her answers about her use of Roundup provided in pre-trial documents.

He said that Stephens and her husband had “changed your story about the length of time you had used Roundup,” saying initially her use dated back to 2003 but then saying the use began in 1985.

Stephens acknowledged that her memories of her use were aided by information from her family.

“You and I agree that one should not swear to something, accuracy, if you don’t know whether it is true or not. That is my question,” Monsanto’s lawyer addressed Stephens.

“At that time, I believed it to be true, yes sir,” she replied.

“You believed it to be true solely because that’s what your husband or your son said, correct?” Williams asked.

“Yes,” Stephens answered.

The line of questioning was anticipated in a June filing by Stephens’ lawyers, explaining to the judge that Stephens is in frail health after six cycles of chemotherapy and has suffered significant memory loss, making her “unable to recall certain Roundup exposures.”

She had told lawyers initially that her exposure extended over 14 years but amended that to say it was closer to 30 years after being reminded of her use of Roundup products at a property where she had previously lived, according to her lawyers.

In their June filing, Stephens lawyers said Monsanto’s attorneys were accusing them and Stephens of “engaging in gamesmanship,” and allegation they denied.

Stephens testified that she does remember that sometimes when she was spraying Roundup the wind would blow spray onto her bare skin. She said she would not immediately wash it off, showering only after she completed her yardwork.

“It was all over me,” Stephens said.

At one point Monsanto’s attorney asked Stephens about her relationship with her children. When Stephens insisted she was close to her children, Monsanto’s attorney played a video deposition of a previous statement she had made saying the opposite.

Longtime Monsanto scientist Donna Farmer is scheduled to testify Tuesday.

Monsanto is owned by Germany’s Bayer AG. Bayer bought Monsanto in 2018.

Preference case

Stephens’ trial is a “preference” case, meaning her case was expedited after her lawyers informed the court that Stephens was “in a perpetual state of pain” and losing cognition and memory.

The case is being tried in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California under the oversight of Judge Gilbert Ochoa. It is the fourth Roundup cancer trial to take place in the United States and the first since 2019. Juries in all three prior trials found in favor of the plaintiffs, agreeing with claims that Monsanto’s glyphosate-based weed killers, such as Roundup, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Monsanto spent decades covering up the risks, and failing to warn users.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The three prior trials were all lengthy, in-person proceedings loaded with weeks of highly technical testimony about scientific data, regulatory matters and documents detailing internal Monsanto communications.

Stephens trial is being held via Zoom due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19, and numerous technical difficulties have plagued the proceedings. On Monday, the trial was stopped several times because jurors lost connections or had other problems that inhibited their ability to hear and view the trial testimony.

September 14, 2021

Son testifies about his mother’s cancer alleged due to Roundup exposure

A woman suffering from non-Hodgkin lymphoma was a devoted user of Roundup herbicide for decades before she became ill, her son testified Tuesday in a California trial that marks the fourth such trial pitting a cancer victim against Roundup maker Monsanto.

Under questioning by a lawyer representing plaintiff Donetta Stephens, her son David Stephens recalled his mother’s frequent use of Roundup in the yard and her tendency to wear sleeveless shirts and shorts when outside spraying the weed killer. He described recalling her use when he was a child and that use continuing when he was an adult and had his own children.

Stephens also testified about a family gathering in which his mother broke the news of her cancer to the family, the lengthy series of medical treatments that followed, his mother’s memory loss and other treatment-related problems, and a period in which his mother was hospitalized multiple times and nearly died.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts in 2015 classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Glyphosate is the active ingredient in Roundup and other weed killing brands.

Bayer AG bought Monsanto in June 2018 just as the first trial was getting underway.

Three previous trials held to date were all found in favor of the plaintiffs. Jurors in those trials agreed with claims that Monsanto’s glyphosate-based weed killers, such as Roundup, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and that Monsanto spent decades covering up the risks and failing to warn users.

The Stephens case is being tried in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California under the oversight of Judge Gilbert Ochoa. Though the trial started in person, Judge Ochoa ordered the proceedings shifted to a Zoom trial due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19 virus.

In testimony Tuesday, David Stephens broke down, emotionally describing a time when it appeared his mother was near death, and speaking of a photo he took of her that he thought at the time would be the last.

“I took that picture because when you think that your mother is going to die and that could be the last picture…,” Stephens said haltingly. “I wanted to take that picture so I could remember…”

Donnetta Stephens is now in remission from cancer but has been left debilitated, her son testified.

Former Monsanto scientist Donna Farmer will be called to testify next week, according to Stephens’ lawyer Fletch Trammell.

Technical trouble

The trial has been plagued by technical issues since the transition to a virtual setting through Zoom. There have been multiple times proceedings have been halted because a lawyer or juror loses an audio or video connection or experiences other difficulties. The virtual format has also proven problematic at times for the presentation of certain exhibits.

A courtroom attendant has been assigned to monitor jurors to determine if they are paying attention, and to alert the judge to lost connections or other problems.

In Tuesday’s testimony, as Monsanto lawyer Manuel Cachan was attempting to cross examine Stephens, questioning the reliability of his memory regarding his mother’s use of Roundup, the technical trouble kicked in again.

“I’m sorry for the interruption, juror number 13 is having issues, just starting to quote unquote glitch out,” the courtroom attendant interjected.

Minutes later: “Pardon me… juror number 11 has just disconnected,” the courtroom attendant interrupted again.

Some legal observers have speculated that the losing party in the trial will have an easy avenue for appeal given the persistent interruptions and difficulties.

Trial overlap

A fifth Roundup trial was starting jury selection this week in a case involving a boy with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The child, Ezra Clark, is the subject of a trial beginning this week in Los Angeles County Superior Court. Clark was “directly exposed” to Roundup many times as he accompanied his mother while she sprayed Roundup to kill weeds around the property where the family lived, according to court documents. Ezra sometimes played in freshly sprayed areas, according to the court filings.

Ezra was diagnosed in 2016, at the age of 4, with Burkitt’s lymphoma, a form of NHL that has a high tendency to spread to the central nervous system, and can also involve the liver, spleen and bone marrow, according to the court filings.

Ezra’s mother, Destiny Clark, is the plaintiff in the case, filing on behalf of Ezra.

Opening statements in the Clark trial are scheduled to begin Wednesday morning.

Bayer denies any cancer connection

Bayer has earmarked more than $14 billion to try to settle the litigation and has announced it will stop selling glyphosate-based herbicides to consumers by 2023. But the company still insists that the herbicides it inherited from Monsanto do not cause cancer.

Last month Bayer filed a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking the high court’s review of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in the case of Hardeman v. Monsanto.

The move is widely seen as Bayer’s best hope for putting an end to claims that exposure to Monsanto’s glyphosate-based herbicides, such as the popular Roundup brand, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and the company failed to warn users of the risks.

During the month-long trial in 2019, lawyers for plaintiff Edwin Hardeman presented jurors with a range of scientific research showing cancer connections to Monsanto’s herbicides as well as evidence of many Monsanto strategies aimed at suppressing the scientific information about the risks of its products. Internal Monsanto documents showed the company’s scientists had engaged in secretly ghost-writing scientific papers that the company then used to help convince regulators of product safety.

August 30, 2021

Bayer Roundup trial goes virtual, and it does not go well

In fits and starts, and with a good dose of frustration over technical difficulties, a California trial pitting an elderly cancer victim against Monsanto owner Bayer AG resumed on Monday in a virtual format after in-person proceedings were suspended last week, reportedly due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19.

Due to an array of technical problems, lawyers for plaintiff Donnetta Stephens were only able to present abbreviated testimony on Monday from expert witness Charles Benbrook, a former research professor who served at one time as executive director of the National Academy of Sciences board on agriculture.

Benbrook is considered a key witness, and is being called to testify about topics that include the history of scientific submissions to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by Monsanto and alleged regulatory shortcomings.

The case, which is being tried in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California under the oversight of Judge Gilbert Ochoa, is the fourth Roundup cancer trial to take place in the United States and the first since 2019. Juries in all three prior trials found in favor of the plaintiffs, agreeing with claims that Monsanto’s glyphosate-based weed killers, such as Roundup, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Monsanto spent decades covering up the risks, and failing to warn users.

Stephens is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The three prior trials were all lengthy, in-person proceedings loaded with weeks of highly technical testimony about scientific data, regulatory matters and documents detailing internal Monsanto communications.

Monday’s proceedings indicated that both sides may face significant challenges in trying to convey and combat the evidence and testimony in a virtual format.

Among the issues on Monday, a court reporter couldn’t fully hear the exchanges between lawyer and witness; jurors had difficulty turning on their computer cameras, a requirement issued by the judge; and the judge himself had to relocate at one point in an effort to improve audio transmission.

A courtroom attendant reassured the judge that he was checking in on the jurors every ten minutes and “it appeared that they were all paying attention.”

At one point when calling a break, Judge Ochoa pleaded: “Ladies and gentleman of the jury please, whatever you do, don’t turn off your computers, don’t touch them, just leave them alone and hopefully everybody’s computer will play nice.”

The judge recessed for the day in mid-afternoon, thanking the jurors for their patience.

“We did have some major technical difficulties,” Judge Ochoa said. He noted, however, that they “did make history” by holding the court’s first “Zoom trial.”

August 24, 2021

Covid delays one Roundup cancer trial while another looms

The California trial pitting an elderly cancer victim against Monsanto owner Bayer AG has been delayed due to concerns about the spread of Covid-19, with proceedings now expected to resume next week in a virtual format via Zoom.

Lawyers for plaintiff Donnetta Stephens say that she was a regular user of Monsanto’s glyphosate-based Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years, an extended exposure that caused her to develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Before the trial interruption jury members heard expert witness testimony from former U.S. government scientist Christopher Portier, who told jurors of multiple scientific studies that support claims glyphosate herbicides cause NHL. Lawyers for Monsanto sought to discredit Portier, and discount his testimony, arguing he had a vested financial interest in helping plaintiffs’ attorneys.

Additional experts were due to testify this week before in-person proceedings were scuttled due to positive cases of the Covid-19 virus showing up among people in the courtroom.

Stephens was diagnosed with NHL in 2017 and has suffered from numerous health complications amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy since then. Because of her poor health, a judge in December granted Stephens a trial “preference,” meaning her case was expedited, after her lawyers informed the court that Stephens is “in a perpetual state of pain,” and losing cognition and memory.

She is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

She and the others who have sued allege that Monsanto has known for decades of scientific research showing its glyphosate herbicides could cause cancer, but has failed to warn users of the risks, working instead to suppress information about potential dangers.

The company lost the three trials held to date.

Trial with child plaintiff is next

Though Bayer last year said it was moving to settle outstanding Roundup lawsuits, many remain active and headed toward trial.

A boy with non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the subject of a trial scheduled for Sept. 13 in Los Angeles County Superior Court. Ezra Clark was “directly exposed” to Roundup many times as he accompanied his mother while she sprayed Roundup to kill weeds around the property where the family lived, according to court documents. Ezra sometimes played in freshly sprayed areas, according to the court filings.

Ezra was diagnosed in 2016, at the age of 4, with Burkitt’s lymphoma, a form of NHL that has a high tendency to spread to the central nervous system, and can also involve the liver, spleen and bone marrow, according to the court filings.

Ezra’s mother, Destiny Clark, is the plaintiff in the case, filing on behalf of Ezra.

Expedited trial sought for dying man

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria, who has been overseeing thousands of Roundup cases through multidistrict litigation proceedings set up in 2016 in federal court in the Northern District of California, has set several upcoming deadlines for moving cases forward that are under his purview. According to a court document filed Monday, close to 4,000 cases have come under Chhabria’s oversight since the inception of the litigation.

Chhabria has ordered lawyers in the litigation to submit to him by Wednesday a list of certain cases that have not yet settled, and proposed schedules for advancing those cases. He also set a case management conference for Sept. 8.

At least one plaintiff is seeking an expedited trial, asking Chhabria to approve trial preference already granted him by a state court judge. Plaintiff Donald Miller was diagnosed with Stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma after using Roundup product for over four decades, according to the court filings.

Miller’s doctor estimated he had a five-year overall survival expectancy of only thirty-seven percent as of

February, 2020, according to court filings. A hearing on the matter is set for Sept. 23.

Many more cases remain pending in state courts, with plaintiffs’ lawyers jockeying for trial dates.

Bayer last week petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to review one of its trial losses. The company claims federal law preempts key claims made in the litigation.

Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, insists that when used as directed, its glyphosate herbicides are safe and do not cause cancer. It says regulatory approvals support its position.

August 16, 2021

Bayer seeks U.S. Supreme Court review of Roundup trial loss

Monsanto owner Bayer AG on Monday filed a petition with the U.S. Supreme Court, seeking the high court’s review of one of its trial losses in the nationwide Roundup cancer litigation.

The move is widely seen as Bayer’s best hope for putting an end to claims that exposure to Monsanto’s glyphosate-based herbicides, such as the popular Roundup brand, cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and the company failed to warn users of the risks. The company has thus far lost three out of three trials, and there are currently more than 100,000 existing plaintiffs as well as many more potential future plaintiffs expected to bring similar claims. Bayer has been trying to settle the cases and come up with a plan to limit, block or settle future claims.

Bayer’s writ of certiorari asks the court to review the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision in the case of Hardeman v. Monsanto.

During the month-long trial in 2019, lawyers for plaintiff Edwin Hardeman presented jurors with a range of scientific research showing cancer connections to Monsanto’s herbicides as well as evidence of many Monsanto strategies aimed at suppressing the scientific information about the risks of its products. Internal Monsanto documents showed the company’s scientists had engaged in secretly ghost-writing scientific papers that the company then used to help convince regulators of product safety.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys argued that Monsanto should have warned consumers about the risks that its products could cause cancer. Lawyers in the other trials Monsanto lost presented similar arguments and evidence of cancer risk.

FIFRA fight

Bayer has said it hopes the Supreme Court will agree with Bayer’s position that the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), which governs the registration, distribution, sale, and use of pesticides in the United States, preempts those “failure-to-warn” claims that are central to the Roundup lawsuits. Because the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved labels with no cancer warning, the failure-to-warn claims should be barred, the company maintains.

The petition filed Monday urges the Supreme Court to review the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision upholding the Hardeman trial loss on the grounds that FIFRA preempts a state-law failure to-warn claim “where the warning cannot be added to a product without EPA approval and EPA has repeatedly concluded that the warning is not appropriate.”

The petition also asks the court to address whether or not the Ninth Circuit’s standard for admitting expert testimony “is inconsistent with this Court’s precedent and Federal Rule of Evidence 702.” Bayer argues that the admission of expert testimony in the Hardeman case “departed from federal standards, enabling plaintiff’s causation witnesses to provide unsupported testimony on the principal issue in the case, Roundup’s safety profile.”

In its petition, Bayer argues: “The Ninth Circuit’s errors mean that a company can be severely punished for marketing a product without a cancer warning when the near-universal scientific and regulatory consensus is that the product does not cause cancer, and the responsible federal agency has forbidden such a warning.”

Hardeman lawyer Aimee Wagstaff said her legal team had been preparing for Bayer’s bid for Supreme Court review.

“While paying out billions of dollars to settle claims, Monsanto continues to refuse to pay Mr. Hardeman’s verdict. That doesn’t seem fair to Mr. Hardeman. Even so, this is Monsanto’s last chance Hail Mary,” Wagstaff said. “We are eager and ready to beat Monsanto at the Supreme Court and put this baseless preemption defense behind us once and for all.”

Bayer cites broad impact

The petition states that the decision in the Hardeman case, which was part of the multidistrict litigation handled in federal court, will “undoubtedly influence still others pending across the country.”

Bayer said in a statement: “The Petition underscores that consistent regulatory assessments in the U.S. and worldwide, and the overwhelming weight of scientific evidence, support the conclusion that glyphosate-based herbicides are safe and not carcinogenic. In light of the EPA’s approval of the Roundup label without a cancer warning, any state-law failure-to-warn claims premised on such warning would plainly conflict with federal law and thus are preempted. Courts across the U.S. have divided on this basic question of when federal law preempts state law, which makes review by the U.S. Supreme Court both important and necessary. Indeed, it has been 16 years since the Supreme Court ruled on FIFRA preemption, and the prior case did not involve a warning that EPA had rejected.”

Lawyers for Hardeman did not respond to a request for comment.

Bayer has so far said it has earmarked more than $16 billion toward settling the Roundup litigation.

August 12, 2021

Scientist testifies in Roundup trial; judge reverses ruling that had helped Monsanto

A former U.S. government scientist testifying in the fourth Roundup cancer trial to be held in the United States told a California jury this week that multiple research studies conducted over many years show an “almost certain” connection between Monsanto glyphosate-based herbicides and cancer.

Christopher Portier, who is testifying as expert witness on behalf of plaintiff Donnetta Stephens in her lawsuit against Monsanto, appeared in person in the courtroom earlier in the week but answered questions from Monsanto’s lawyer via Zoom on Thursday due to travel commitments.

Portier was also an expert witness for the plaintiffs in the three prior Roundup trials. In each of the prior trials, juries agreed that Monsanto’s glyphosate herbicides caused the plaintiffs to develop a type of cancer called non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

In hours of testimony that stretched over several days, Portier told jury members about studies done on human cell lines as well as studies conducted on laboratory animals and studies of exposure and disease incidence in humans. The evidence of a cancer connection was strongest in the animal studies, and was supported by the additional research, he said.

“I am certain that glyphosate can cause tumors in animals,” including malignant lymphomas in mice, Portier testified. When asked his opinion on the question of whether or not real-world Roundup exposure can cause NHL in people, Portier said: “I believe that it does, I think the strength of that belief is almost certain but not quite.”

Regular Roundup user

Lawyers for Stephens say that she was a regular user of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years and it was that extended exposure to the glyphosate-based products made popular by Monsanto that caused her NHL.

Stephens was diagnosed in 2017 and has suffered from numerous health complications amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy since then. Because of her poor health, a judge in December granted Stephens a trial “preference,” meaning her case was expedited, after her lawyers informed the court that Stephens is “in a perpetual state of pain,” and losing cognition and memory.

She is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Judge Gilbert Ochoa of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California is overseeing the proceedings.

Judge reverses order on preemption

In a move that could prove important to the outcome of the case, Judge Ochoa this week reversed his own pretrial ruling related to Monsanto’s argument that federal law preempts the “failure to warn” claims that Stephens’ lawyers want to present to the jury.

The judge had agreed with Monsanto that federal law regarding pesticide regulation and labeling preempts failure-to-warn claims under state law, and he had limited the ability of Stephens’ lawyers to pursue such claims.

But the judge changed his position after the 1st Appellate District in the Court of Appeal for California issued a ruling on Monday denying Monsanto’s preemption argument in a separate case.

The appeals court issued scathing criticism of Monsanto, writing that “substantial evidence supports the jury’s verdicts” and that “Monsanto’s conduct evidenced reckless disregard of the health and safety of the multitude of unsuspecting consumers it kept in the dark.”

The day after the appeals court ruling, Monsanto noted in a brief filed with Judge Ochoa that it recognized the appellate court decision was “binding” on the San Bernardino court, but said the appeals court “committed legal error.”

Monsanto owner Bayer AG has said publicly it sees its best hope of escaping ongoing litigation in persuading the U.S. Supreme Court to review and overturn one of the trial losses on the preemption issue.

Another trial sought in St. Louis

After losing the first three trials, Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, has settled other cases that had been scheduled to go to trial. And in 2020, the company said it would pay roughly $11 billion to settle about 100,000 existing Roundup cancer claims. Late last month, Bayer said it would set aside another $4.5 billion toward Roundup litigation liability.

Bayer also announced it would stop selling Roundup, and other herbicides made with the active ingredient glyphosate, to U.S. consumers by 2023. But the company continues to sell the products for use by farmers and commercial applicators.

But several law firms continue to seek to bring cases to trial. In late July, lawyers for a group of 13 plaintiffs filed a motion with the St. Louis County Circuit Court seeking a trial date. That case is 19SL-CC04115, Kyle Chaplick et al v Monsanto.

August 9, 2021

Monsanto owner Bayer AG has lost another appeals court decision in the sweeping U.S. Roundup litigation, continuing to struggle to find a way out from under the crush of tens of thousands of claims alleging that Monsanto’s glyphosate-based herbicides cause cancer.

In a decision handed down on Monday, the 1st Appellate District in the Court of Appeal for California rejected Monsanto’s bid to overturn the trial loss in a case brought by husband-and-wife plaintiffs, Alva and Alberta Pilliod.

“We find that substantial evidence supports the jury’s verdicts,” the court stated. “Monsanto’s conduct evidenced reckless disregard of the health and safety of the multitude of unsuspecting consumers it kept in the dark. This was not an isolated incident; Monsanto’s conduct involved repeated actions over a period of many years motivated by the desire for sales and profit.”

The court specifically rejected the argument that federal law preempts such claims, an argument Bayer has told investors offers a potential path out of the litigation. Bayer has said it hopes it can get the U.S. Supreme Court to agree with its preemption argument.

In May 2019 a jury awarded the Pilliods more than $2 billion in punitive and compensatory damages after lawyers for the couple argued they both developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma caused by their many years of using Roundup products.

The trial judge lowered the combined award to $87 million.

In appealing the loss, Monsanto argued not only that the Pilliod claims were preempted by federal law, but also that the jury’s causation findings were flawed, the trial court should not have admitted certain evidence, and that “the verdict is the product of attorney misconduct.” Monsanto also wanted the damage awards further slashed.

Court slams company

In the appeals court decision, the court left the award unchanged, and said that Monsanto had not shown that federal law did preempt such claims as those made by the Pilliods. The court also said there was substantial evidence that Monsanto acted with a “willful and conscious disregard for the safety of others,” supporting the awarding of punitive damages.

The evidence showed that Monsanto “failed to conduct adequate studies on glyphosate and Roundup, thus impeding discouraging, or distorting scientific inquiry concerning glyphosate and Roundup,” the court said.

The court also chastised Monsanto for not accurately presenting “all of the record evidence” in making its appeal: “But rather than fairly stating all the relevant evidence, Monsanto has made a lopsided presentation that relies primarily on the evidence in its favor. This type of presentation may work for a jury, but it will not work for the Court of Appeal.”

The court added: “The trial described in Monsanto’s opening brief bears little resemblance to the trial reflected in the record.”

“Summed up, the evidence shows Monsanto’s intransigent unwillingness to inform the public about the carcinogenic dangers of a product it made abundantly available at hardware stores and garden shops across the country,” the court said.

Another trial underway now

The Pilliod trial was the third against Monsanto. In the first trial, a unanimous jury awarded plaintiff Dewayne Johnson $289 million; the plaintiff in the second trial was awarded $80 million.

The fourth trial began last week. A jury of seven men and five women on Monday were hearing testimony in the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California. Retired U.S. government scientist Christopher Portier, who has been an expert witness for the plaintiffs in prior Roundup trials, testified at length on Monday, reiterating previous testimony that there is clear scientific evidence showing glyphosate and glyphosate-based formulations such as Roundup can cause cancer.

Bayer, which bought Monsanto in 2018, has settled several other cases that were scheduled to go to trial over the last two years. And in 2020, the company said it would pay roughly $11 billion to settle about 100,000 existing Roundup cancer claims. Late last month, Bayer said it would set aside another $4.5 billion toward Roundup litigation liability.

Bayer also announced it would stop selling Roundup, and other herbicides made with the active ingredient glyphosate, to U.S. consumers by 2023. But the company continues to sell the products for use by farmers and commercial applicators.

August 4, 2021

Bayer heads into next U.S. cancer trial, opening statements set for Thursday

Despite Bayer AG’s efforts to put an end to costly litigation inherited in its acquisition of Monsanto, opening statements in yet another trial are set for Thursday as a woman suffering from non-Hodgkin lymphoma claims Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide caused her cancer.

A jury of seven men and five women have been seated in the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto in the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California. Judge Gilbert Ochoa was hearing last-minute arguments over evidence on Wednesday.

The trial comes a week after Bayer announced it would stop selling Roundup, and other herbicides made with the active ingredient glyphosate, to U.S. consumers by 2023. Monsanto was purchased by Bayer AG in 2018, and Bayer insists, just as Monsanto has for decades, that there is no valid evidence of a cancer connection between its weed killing products and cancer.

Bayer said the move to stop selling the herbicides to consumers was “to manage litigation risk and not because of any safety concerns.” The company said it will continue to sell its glyphosate-based herbicides for commercial use and for use by farmers.

Bayer also said last week it was setting aside $4.5 billion – on top of roughly $11 billion already earmarked for Roundup litigation settlements – to cover “potential long-term exposure” to liability associated with claims from cancer victims such as Stephens.

Bayer further said with respect to ongoing litigation, it “will be very selective in its settlement approach in the coming months.”

Evidence at issue

Ahead of the opening statements in the Stephens trial, many issues were being argued without the jury present on Wednesday in front of Judge Ochoa, including the scope of allowable arguments by plaintiffs that Monsanto should have provided warnings to Roundup users that certain scientific research showed links between its products and cancer.

Judge Ochoa earlier ruled – in agreement with Monsanto – that federal law regarding Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) oversight of pesticide product labeling preempts “failure to warn” claims under state law, meaning Stephens’ lawyers would not be able to pursue such claims.

The plaintiffs still hope to argue, however, that separate from the labeling issues, Monsanto could have, and should have, warned consumers about the potential cancer risk in other ways, according to Stephens’ lawyer Fletcher Trammell. He and Stephens’ other lawyers will seek to prove that Monsanto made an unsafe herbicide product and knowingly pushed it into the marketplace despite scientific research showing glyphosate-based herbicides could cause cancer.

Lawyers for Stephens say that she was a regular user of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years and it was that extended exposure to the glyphosate-based products made popular by Monsanto that caused her non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Stephens was diagnosed in 2017 and has suffered from numerous health complications amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy since then. She is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The list of evidence to be presented at trial runs more than 250 pages and includes scientific studies as well as Monsanto emails and other internal corporate documents. A federal judge who has been overseeing nationwide Roundup litigation stated in a recent order that there is “a good deal of damning evidence against Monsanto—evidence which suggested that Monsanto never seemed to care whether its product harms people.”

Close to 70 people are listed as witnesses to testify at trial, either live or through deposition testimony, including many former Monsanto scientists and executives.

The first witness set to take the stand is retired U.S. government scientist Christopher Portier, who has been an expert witness for the plaintiffs in each of the prior Roundup trials. Portier has previously testified that there is clear scientific evidence showing glyphosate and glyphosate-based formulations such as Roundup can cause cancer in people. He has also testified in the past that U.S. and European regulators have not properly assessed the science and have ignored research showing cancer concerns with Monsanto’s herbicides.

Before retiring, Portier led the National Center for Environmental Health/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prior to that role, Portier spent 32 years with the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, where he served as associate director, and director of the Environmental Toxicology Program, which has since merged into the institute’s National Toxicology Program. Portier was also an “invited specialist” to the International Agency for Research on Cancer unit of the World Health Organization when the group made its probable carcinogen classification of glyphosate in 2015.

Bayer hopes for help from Supreme Court

Monsanto has lost three out of three previous trials, with a jury in the last trial – held in 2019 – ordering a staggering $2 billion in damages due to what the jury saw as egregious conduct by Monsanto in failing to warn users of evidence – including numerous scientific studies – showing a connection between its products and cancer. (The award was later shaved to $87 million.)

In trying to free itself from the weight of Monsanto-related woes, Bayer said last week that in addition to replacing its glyphosate-based products in the U.S. residential market with new formulations using alternative ingredients, it is exploring changes to Roundup labeling.

“It is important for the company, our owners, and our customers that we move on and put the uncertainty and ambiguity related to the glyphosate litigation behind us,” Bayer CEO Werner Baumann said during a recent investor call.

The company also said it will file a petition this month seeking U.S. Supreme Court review of one of its trial losses – the case of Hardeman v. Monsanto. Bayer said if the Supreme Court grants review, the company “will not entertain any further settlement discussions” while the court reviews the appeal.

In the event of a “negative Supreme Court outcome,” Bayer said it would set up a claims’ administration program that will offer “pre-determined compensation values” to “eligible individuals” who used Roundup and developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma over the next 15 years.

July 26, 2021

New Roundup cancer trial starting in California

Lawyers representing a woman suffering from cancer are prepared to face off against Monsanto and its German owner Bayer AG in a California courtroom on Monday in what is set as the fourth trial over allegations Monsanto’s popular Roundup weed killers cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

Jury selection in the case of Donnetta Stephens v. Monsanto is expected to take several days and the trial itself is expected to last up to eight weeks. Judge Gilbert Ochoa of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California is overseeing the proceedings.

Monsanto has lost three out of three previous trials, with a jury in the last trial – held in 2019 – ordering a staggering $2 billion in damages due to what the jury saw as egregious conduct by Monsanto in failing to warn users of evidence – including numerous scientific studies – showing a connection between its products and cancer. (The award was later shaved to $87 million.)

Lawyers for Stephens say that she was a regular user of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years and it was that extended exposure to the glyphosate-based products made popular by Monsanto that caused her NHL.

Stephens was diagnosed in 2017 and has suffered from numerous health complications amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy since then. Because of her poor health, a judge in December granted Stephens a trial “preference,” meaning her case was expedited, after her lawyers informed the court that Stephens is “in a perpetual state of pain,” and losing cognition and memory.

She is one of tens of thousands of plaintiffs who filed U.S. lawsuits against Monsanto after the World Health Organization’s cancer experts classified glyphosate – the active ingredient in Monsanto’s herbicides – as a probable human carcinogen with an association to non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Judge Ochoa has made several pretrial rulings, including agreeing with Monsanto that federal law regarding pesticide regulation and labeling preempts “failure to warn” claims under state law and Stephens’ lawyers would not be able to pursue such claims.

The plaintiffs still will be able to argue that separate from the labeling issues, Monsanto could have, and should have, warned consumers about the potential cancer risk in other ways, according to Stephens’ lawyer Fletcher Trammell. He and Stephens’ other lawyers will seek to prove their claims that Monsanto made an unsafe herbicide product and knowingly pushed it into the marketplace despite scientific research showing glyphosate-based herbicides could cause cancer.

Monsanto was purchased by Bayer AG in 2018 and is no longer a stand-alone company but is the named defendant in ongoing litigation. Bayer insists, just as Monsanto has for decades, that there is no valid evidence of a cancer connection between its weed killing products and cancer.

Questions for the Jury

Jury selection is deemed a critical part of any trial and as the opposing sides look at the pool of prospective jurors for the Stephens trial they will be screening them for signs of bias. According to a jury questionnaire, among the questions jurors are to be asked are these:

- Do you believe most companies’ scientific studies regarding safety are altered to further a specific agenda?

- Do you have any opinions about how well most corporations communicate safety information about their products to the public?

- Do you, or does anyone close to you, have any health problems or concerns resulting from any products you or they have used or been around?

- Do you believe that any exposures to hazardous chemicals, no matter how small, is harmful to humans?

The jurors who are selected will face a daunting amount of evidence, including scientific studies and internal Monsanto records. The list of evidence, in the form of ‘exhibits’ to be presented at trial, runs more than 250 pages and includes many damning Monsanto emails and other documents that led a federal judge who has been overseeing nationwide Roundup litigation to state in a recent order that the trials have provided “a good deal of damning evidence against Monsanto—evidence which suggested that Monsanto never seemed to care whether its product harms people.”

There also will be many witnesses involved in the trial. Stephens’ lawyers have listed 39 people they intend to call to testify, including deposition testimony of Monsanto scientist Donna Farmer, former Monsanto Chairman Hugh Grant, and multiple other Monsanto executives.

Monsanto’s witness list includes many of the company’s executives and scientists as well as former Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) official Jess Rowland, who has been revealed as an ally and friend to the company in the ongoing litigation. Monsanto has listed a total of 32 individuals as witnesses for the defense.

Bayer Looking for a Win

In the first trial against Monsanto, a unanimous jury awarded plaintiff Dewayne Johnson $289 million; the plaintiff in the second trial was awarded $80 million; and the jury in the third trial awarded more than $2 billion to husband-and-wife plaintiffs. All the awards were reduced sharply by judges involved in the cases but the verdicts assigning blame to Monsanto for the cancers have not been overturned.

Bayer sees the preemption argument as critical to its ability to limit the ongoing litigation liability. The company has made it clear that it hopes at some point to get a U.S. Supreme Court finding that under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), the EPA’s position that Monsanto’s herbicides are not likely to cause cancer essentially bars complaints that Monsanto didn’t warn of any cancer risk.

Even as it pursues a preemption ruling, Bayer said last year that it had agreed to pay close to $11 billion to settle existing Roundup cancer claims. But many law firms have dismissed the individual offers for their clients as insufficient, and they continue to press for more trials.

Bayer said recently it is considering pulling Roundup products from the U.S. market for residential users, though not from farm use.

Bayer gets lift in pre-trial ruling ahead of Roundup cancer trial

A California judge gave Monsanto and its German owner Bayer AG a pre-trial boost in a ruling issued Monday, a week before the scheduled start of a new courtroom challenge to the safety of Monsanto’s Roundup herbicides.

Judge Gilbert Ochoa of the Superior Court of San Bernardino County in California agreed with Monsanto that federal law regarding pesticide regulation and labeling preempts “failure to warn” claims under state law, and the plaintiff in the trial set to start next week will not be allowed to pursue such claims.

“The Court grants Defendant Monsanto Motion for Summary Adjudication of the 2nd and 4th causes of action on the grounds the failure to warn or concealment of glyphosate’s link to cancer is expressly and/or impliedly preempted” by federal law, Ochoa wrote in his order.

The decision was “surprising” to plaintiff’s attorney Fletcher Trammell, who is representing plaintiff Donnetta Stephens in the case against Monsanto. “Obviously we disagree,” he said. The issue could be subject of appeal at some point, he added.

The claims that Monsanto made an unsafe product and knowingly pushed it into the marketplace remain intact and will be presented at trial, according to Trammell.

More Than Two Years

It’s been more than two years since Bayer has had to defend the safety of Monsanto’s weed killing products at a trial. Monsanto has lost three out of three previous trials, with a jury in the last trial ordering a staggering $2 billion in damages due to what the jury saw as egregious conduct by Monsanto in failing to warn users of evidence – including numerous scientific studies – showing a connection between its products and cancer.

Lawyers for Stephens, a regular user of Roundup herbicide for more than 30 years, will try to prove that exposure to the glyphosate-based products made popular by Monsanto caused Stephens to develop non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

The case is set for trial Monday July 26, delayed by one week as the court deals with a variety of pre-trial motions. Stephens was diagnosed with NHL in 2017 and has suffered from numerous health complications amid multiple rounds of chemotherapy since then. Because of her poor health, a judge in December granted Stephens a trial “preference,” meaning her case was expedited, after her lawyers informed the court that Stephens is “in a perpetual state of pain,” and losing cognition and memory.

Several other cases have either already been granted preference trial dates or are seeking trial dates for other plaintiffs, including at least two children, suffering from NHL the plaintiffs allege was caused by exposure to Roundup products.

Monsanto was purchased by Bayer AG in 2018 and is no longer a stand-alone company but is the named defendant in ongoing litigation, which began in 2015 after cancer experts consulted by a unit of the World Health Organization determined glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen with a particular association to NHL.

Roughly 100,000 people in the United States have claimed they developed NHL because of their exposure to Roundup or other Monsanto-made glyphosate-based herbicides.

Preemption Argument

Bayer sees the preemption argument as critical to its ability to limit the ongoing litigation liability. The company has made it clear that it hopes at some point to get a U.S. Supreme Court finding that under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) position that Monsanto’s herbicides are not likely to cause cancer essentially bars complaints that Monsanto didn’t warn of any cancer risk.