Money to Burn

More than 300 banks and investors back six of the world’s most harmful agribusinesses to the tune of $44bn

The burning of the Brazilian Amazon this summer illustrated in the most graphic way possible humanity’s war on the planet.

But such scenes play out every year in rainforests all around the world to make way for big agribusiness, away from the horrified stare of global television audiences. These forests are earth’s front-line defence against climate breakdown. One famous study published in 2017 estimated that forests and other ecosystems could make up more than a third of the total carbon mitigation by 2030 needed to limit global heating to a 2° Celsius rise.

Yet between 2001 and 2015, over 300 million hectares of tree cover was destroyed: nearly the size of India. About a quarter of this loss was driven by the production of commodities such as beef and palm oil, according to a recent study. It also found that in south-east Asia alone, deforestation for growing commodities such as palm oil is responsible for as much as 78% of tree cover loss. This is madness.

That being the case, it is unsurprising many banks and investors proudly trumpet policies on ethical dealing, promising not to pump money into companies that fell and burn precious rainforests. There is only one problem: the same financial institutions often break their own policies at will, making them barely worth the paper they are printed on. A Global Witness investigation now exposes the sheer size and scale of these financial flows – and reveals how a veritable A to Z of global finance is enabling the destruction of the world’s biggest rainforests.

The companies razing forests to produce palm oil, beef, and rubber are currently able to secure financing for new projects at commercially attractive rates from banking hubs in the US, Europe and Asia. Global Witness investigated the financing of six huge agribusinesses: three operating in the Amazon, two in the Congo Basin, and one in New Guinea.

Global Witness has discovered that between 2013 and 2019, they were backed to the tune of $44 billion by over 300 investment firms, banks, and pension funds headquartered across the globe. The household name institutions our exposé highlights will be familiar to anyone who has looked at the skyline of Wall Street or Canary Wharf, read a quality newspaper or opened a current account.

While some of these institutions have developed their own deforestation policies, there is no penalty if they ignore them – and they often do. Governments’ failure to regulate the financing of deforestation has left the foxes in charge of the hen-house. Members of the public may be shocked to learn the institutions they bank with enable the sort of apocalyptic destruction witnessed in the Brazilian Amazon this summer.

Ordinary people’s pension funds and investments are channelled into companies revving up the climate crisis, stripping indigenous peoples of their ancestral lands and destroying the forests home to untold numbers of species.

Over the last decade, many financial institutions have committed to tackling deforestation, so often associated with human rights abuses or corruption. One group of 56 investors managing approximately $7.9 trillion in assets has urged the palm oil sector to commit to no-deforestation policies. Some 12 banks adopted the Soft Commodities Compact, aiming to achieve net zero deforestation by 2020 in the soy, palm oil, beef and pulp/paper supply chains of around 400 companies with combined sales of 3.5 trillion euros.

But there remains little transparency and accountability over how banks put commitments into practice, and signatories now admit they will miss the 2020 target. Meanwhile, the world’s largest financial institutions continue to sink vast sums into companies either levelling forests themselves or via other companies, often in blatant violation of their own deforestation policies and public commitments.

The NGO Global Canopy assessed 150 financial institutions and found nearly two-thirds had no policy covering four key forest-risk commodities, beef, soy, palm oil and timber. Yet as our investigation shows, even existing policies are widely ignored.

Global Witness can now reveal some of the largest names in global finance – Barclays, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Santander and Standard Chartered among them—provided tens of billions of dollars in financing between 2013 and 2019 to companies either directly or indirectly deforesting the largest rainforests in the world. Leading investment banks including JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and Morgan Stanley are also implicated. And what you are about to read only scratches the surface of a global systems failure.

What we did

Global Witness commissioned research from Dutch not-for-profit analysts Profundo into backers of six of the major agribusinesses most implicated in destruction of climate-critical rainforests. They used databases of loans, investments and other types of financing kept by Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters Eikon, Orbis and others, along with company reports and websites to build up a picture of how these companies finance their operations. It was impossible to determine which specific ground-level activities this money financed – but such funding is critical to agribusinesses’ expansion.

This sprawling piece of data journalism reveals with new starkness the golden sinews that link London, Berlin and New York City to the dwindling rainforests of the Amazon, the Congo Basin and the island of New Guinea. These are the three largest uninterrupted rainforest regions in the world.

The Brazilian Amazon

A few years ago, deforestation in the Amazon was declining, partly thanks to government action. But that progress is being undone under the rule of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, with cattle ranching the biggest culprit, according to numerous industry studies.

The three largest beef companies in the Brazilian Amazon, JBS S.A., Marfrig Global, and Minerva Foods, account for more than 45% of the region’s cattle-slaughtering capacity. All three have committed to measures that should help protect the forest. Yet their supply chain is tainted by deforestation – and famous names in finance help keep them afloat.

JBS, the world’s biggest meatpacker, has a history of buying animals from deforested areas. A decade ago, responding to pressure from Greenpeace, JBS signed an agreement not to buy cattle from suppliers that had deforested land after October 2009. They also vowed not to source cattle from suppliers that used slave labor or infringed on indigenous communities’ lands.

Finally, JBS committed never to purchase cattle from suppliers embargoed by the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) for illegal deforestation, nor from suppliers that raised, reared, or fattened cattle on land overlapping with protected areas. In 2009, JBS became a party to a similar agreement with the Federal Prosecutor’s Office in the Amazonian state of Pará. Since then, however, the company has made a mockery of these commitments:

- In 2015, JBS was accused by the Brazilian Federal Police of having bought hundreds of cattle from the mother of an alleged land-grabber described by the police as the “largest deforester of the Amazon”. The suspected land-grabber has been tried and is awaiting verdict. JBS said it has blocked the sourcing of cattle from the land-grabber’s mother and claimed that auditing had shown the company was over 99% compliant with its Greenpeace commitment.

- In 2017, Ibama discovered two JBS slaughterhouses had bought 49,468 cattle from embargoed areas, for which the company was fined 24.7 million reais, almost $8 million at a 2017 conversion rate. Global Witness estimates these cattle purchases may have required up to 38,000 hectares of deforestation. JBS denied the purchasing claims, saying it does not buy animals from farms involved in deforestation of native forests or areas embargoed by Ibama.

- Last year, the Amazonian state of Pará published an audit of JBS that found breaches of its commitments covering almost 20% of its 2016 cattle purchases. Global Witness estimates the cattle JBS bought that year from ranchers responsible for deforestation may have required an area the size of 65,000 football pitches. JBS said they had been hindered by the lack of detail on the criteria for analysis and by discrepancies in the databases of public sector institutions. It said it had selected an auditor with a “conservative” view in the cases where there were doubts about the information.

- An investigation carried out by Repórter Brasil, the Guardian and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in July alleged the company was still purchasing cattle from embargoed areas. JBS denied this claim.

JBS told Global Witness the issues raised about the company’s environmental policies make “no sense” because it had “implemented rigorous systems and controls” and “does not purchase from farms involved in deforestation”.

Given these transgressions, it might be surprising JBS can attract mainstream financing at all. In fact, it enjoys support from some of the world’s wealthiest banks and investment managers. After a family-owned holding company that is the largest shareholder, its second-largest investor is BNDES, the biggest development bank in the Americas. BNDES held over $2.7 billion of JBS stock as of April 2019.

It is perhaps unsurprising Brazil’s development bank would aid the expansion of the country’s biggest companies. (BNDES did not respond to Global Witness’s inquiries.)

But where else does JBS receive financial succour? Step forward the US and Germany.

For JBS’s next largest investor is the American Capital Group, which claims to manage over $1.7 trillion in equity and fixed income assets for millions of investors. According to our research, it held shares in JBS worth over $800 million as of March 2019. Then comes BlackRock. Headquartered in New York with offices in 30 countries, this is another of the richest and most powerful financial institutions in the world, managing more than $6 trillion in assets. As of May 2019, these investments included over $218 million of JBS stock. Global Witness could find no deforestation policy on either fund’s website. Capital Group declined to comment on Global Witness’s findings, and BlackRock did not respond to our enquiries.

Since 2017, Deutsche Bank’s environmental policy has stated it will not knowingly finance projects or activities involving the clearance of primary moist tropical forests. As of April 2019, however, it held over $11 million in JBS shares. In addition, albeit pre-dating the policy, in 2013 it loaned the company $56.7 million.

This is not the first time Deutsche Bank has been accused of irresponsible investments. In 2013, Global Witness revealed how two Vietnamese companies, bankrolled by Deutsche Bank, leased vast tracts of land for rubber plantations in Laos and Cambodia – with disastrous consequences for local communities and the environment.

A Deutsche Bank spokesman said they were unable to comment on client relationships, but added: “We can reaffirm that we take our responsibilities for the environment and society very seriously. We apply our environmental and social risk management policies and procedures in the assessment of any new or existing client relationship. The information you provided is much appreciated and will be considered in any potential decision we have to take.”

But there are also major red flags that JBS’s competitors acquire cattle from deforested land.

Marfrig Global Foods claims to be one of the world’s leading beef producers. Its beef division boasts 28 operating units that can slaughter 21,500 cattle per day in total. In 2009, it signed the same Greenpeace pledge as JBS. But research by Brazilian NGO Imazon, published in 2017, found Marfrig’s Amazon slaughterhouses could be buying cattle from deforestation-risk areas covering over 1.3 million hectares, including properties embargoed by Ibama for illegal deforestation and places deforested between 2010 and 2015.

Furthermore, the Imazon report claimed half the company’s cattle purchases come from ‘indirect suppliers’, where animals pass through numerous ranches before slaughter. As part of Marfrig’s Greenpeace pledge, they had agreed not to purchase any cattle from indirect suppliers who had deforested the Amazon. Yet in four successive audits of the company’s Amazon cattle purchases between 2015 and 2018, its auditor DNV-GL concluded: “Indirect suppliers are not systematically verified yet.”

This means Marfrig cannot say its supply chain is deforestation free. (Marfrig insisted to Global Witness that it had a commitment to zero deforestation in the Amazon, with a rigorous and technologically advanced sourcing procedure.)

Moreover, this August, Repórter Brasil disclosed that a cattle rancher carried out illegal deforestation in Pará and laundered cattle from that area through another property to make them appear legal. Ibama investigated and the property was embargoed. Repórter Brasil claimed Marfrig purchased cattle from the property despite Ibama’s embargo, breaching the company’s commitment to not purchase cattle from such areas.

The municipality where this ranch was located, São Félix do Xingu, was among those highlighted after recent Amazon fires led to an international outcry. Marfrig argues the ranch was not on Ibama’s index of embargoed areas when they purchased the cattle. Repórter Brasil disputes this, finding the area was on Ibama’s publically available list prior to the purchase.

Yet these warning signs have not deterred Marfrig’s financiers – despite public commitments to ethical dealing. Global Witness estimates Santander, the largest bank in the Eurozone, underwrote over $1 billion in financing to Marfrig between 2013 and 2018, including more than $300 million in 2018 alone.

Santander committed to the Soft Commodities Compact in 2014. However, the bank’s soft commodities policy does not explicitly prohibit financing activities that involve deforestation. A Santander spokeswoman said: “As a responsible bank, we share your concern regarding social and environmental impacts linked to our financing activities. In Brazil, we conduct annual reviews of more than 2,000 clients, including large soy producers, soy traders and meatpackers, especially about their supply chain. At the time of our analyses, Marfrig was in compliance with these agreements [with Greenpeace and another with the Brazilian government], which involved third-party audits of ranchers.”

The bank did not address the fact that Marfrig is not in compliance with the Greenpeace pledge in relation to systematically verifying its indirect suppliers, as flagged by successive audits from its auditor DNV-GL. Although Santander’s financing took place before the recent Repórter Brasil allegations against Marfrig, these are of obvious relevance to decisions about whether to do business with the company in future.

Marfrig also enjoys major US investment. Its second-largest shareholder is the San Diego-based Brandes Investment Partners, which held $94.8 million in stock at the time of this research. Shockingly, Brandes’s “Responsible Investment Statement” explicitly states it does notautomatically avoid investment in any industry or company based on its ESG (environmental, social and governance) practices. The financier did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

A third major beef company based in Brazil, Minerva Foods, prides itself on being a South American leader in the “production and sale of fresh beef and its byproducts”. From beef to leather to tallow biodiesel, Minerva offers it all. But the NGO Imazon found that, like Marfrig, Minerva’s Amazon slaughterhouses could be buying cattle from almost one million hectares of land at risk of deforestation, areas embargoed by Ibama and areas deforested between 2010 and 2015. Despite also signing the Greenpeace pledge, Minerva too buys cattle from indirect suppliers, which the company claims is challenging to monitor. Thus it too cannot say it complies with the Greenpeace zero-deforestation pledge.

Yet Bank of America seems unconcerned. Global Witness estimates based on Profundo’s research that, as Minerva’s largest US creditor, the bank underwrote nearly half a billion dollars in credit for the company in the period surveyed. (It also provided over $50 million in loans to Marfrig.) This is despite the bank’s current Forest Practices Policy forbidding it from financing deforestation activities in primary tropical moist forests, intact forests, or high-conservation value forests, but only at the level of specific on-the-ground projects. Bank of America did not respond to several Global Witness requests for a comment.

Yet this is not Minerva’s only big name financial backer. In 2013, even the World Bank – which aims to combat poverty worldwide and touts its investments in “sustainable solutions” – gave a ten-year loan to the company via the International Finance Corporation worth 137 million reais (approximately $61 million at 2013 exchange rates). Several years later, the bank embraced a new Forests Action Plan. One of its aims is to not have “interventions in other sectors come at the cost of forest capital”.

A spokesman for the World Bank said Minerva had to adhere to its “Performance Standards”, which included staying in “close contact” with one supervisory visit a year. The spokesman said all Minerva’s direct purchases were from zero deforestation areas, but admitted monitoring indirect suppliers was “extremely challenging,” stating that “further progress” against deforestation depends on government legislation and law enforcement in Brazil.

“As of today, none of the players… are able to trace indirect suppliers,” the spokesman admitted. “This does mean Minerva (and other signatories) does not yet meet Greenpeace’s requirement.” “We share your concerns on this important issue,” the spokesman concluded, arguing Minerva was a “high performer” compared to other Brazilian beef companies. For its part, Minerva told Global Witness: “We proudly reinforce our commitment to manage and mitigate… deforestation,” insisting Imazon’s report did not mean its slaughterhouses did in actuality purchase cows from deforested areas.

None of this is good enough for Greenpeace Brasil, which signed the three companies up to its pledges back in 2009. Amazon Campaigner Adriana Charoux told Global Witness: “Despite the three biggest beef traders in Brazil having made commitments to control their indirect suppliers, until now they have done nothing toward that aim. This exposes them to suppliers that still deforest and destroy the Amazon for production.”

Congo Basin

Smallholder agriculture is the major driver of deforestation across central Africa’s Congo Basin, but the threat of large-scale industrial agriculture is expected to grow. A rash of concessions since 2003 have already seen an estimated 1.3 million hectares of land allocated to industrial agriculture, including oil palm and rubber.

In 2016, as part of a merger with the Chinese conglomerate Sinochem to create the world’s largest rubber supply chain manager, Singapore’s Halcyon Agri Corp took control of rubber plantations in Cameroon spanning tens of thousands of hectares. These plantations adjoin the Dja Faunal Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage site home to lowland gorillas and chimpanzees. Breaking up blocks of forest is one of the foremost causes of tropical biodiversity loss.

According to a Greenpeace analysis, the plantations’ local operator Sudcam cleared over 11,600 hectares of forest between 2011 and December 2018. Based on an expert carbon stocks analysis undertaken for Global Witness by the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, this emitted the equivalent of over 11 million tonnes of CO2, more than the UK’s entire industrial process emissions in 2017.

Some 2,300 hectares of this forest, an area greater than Geneva, was cleared between April 2017 and April 2018, after Halcyon acquired a controlling stake in Sudcam. The project has also been criticized for its profound impact on communities in the area – including indigenous Baka Forest People groups — who depend on the forests. Many have reportedly been forced from their homes and denied access to their customary lands.

In 2015, major banks including ABN Amro, the third-largest bank in the Netherlands, and Singapore’s DBS Bank, facilitated a three-year, $388 million revolving credit package for Halcyon. This is a form of loan that a company can repeatedly draw down, similar to an overdraft. Although this financing was approved before Halcyon took control of the plantations in Cameroon, these financiers failed to withdraw support when Halcyon became involved in deforestation.

In its 2019 sustainability policy, DBS states it requires new borrowers in the palm oil sector to “demonstrate alignment” with NDPE (no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation) policies. It also prohibits the conversion of HCV and HCS [high conservation value and high carbon stock] forests into palm oil plantations.

ABN Amro said: “We would like to state that ABN Amro Bank has not financed any rubber producers since 2017.” Pushed on whether it did any due diligence on Halcyon, a spokesman added: “As a matter of privacy policy, ABN Amro does not comment on individual client relationships. In general however, our policy as regards to accepting clients in high-risk sectors [or] countries … is to always perform an ESG assessment.” DBS did not respond to persistent enquiries from Global Witness.

Zürich-based giant wealth manager Credit Suisse also helped to facilitate the credit facility, and separately arranged a bond issuance for Halcyon Agri in 2017. A spokesman for the bank told Global Witness the revolving credit facility and bond issuance to Halcyon pre-dated the publication of Greenpeace’s report and proceeds funded Halcyon’s rubber activities in south-east Asia, not Cameroon.

The spokesman also stated that based on due diligence before the bond issuance, “which included discussions on environmental and social matters … we perceived issues with Halcyon Agri operations in Cameroon were being adequately addressed at the time”.

In July 2018, Greenpeace labelled Halcyon’s Cameroon operations “the most devastating new forest clearance for industrial agriculture in the Congo basin.” At the end of that year, the company announced an end to deforestation inside the Sudcam concessions. These changes came too late for one of Halcyon’s major investors, the giant Government Pension Fund of Norway. In 2019, it announced it would from Halcyon based on an “unacceptable risk that the company is responsible for serious environmental damage.”

But as of March 2018, the China Development Bank was Halcyon’s largest investor by far, holding over $73 million worth of shares. The bank does not publish a policy related to deforestation, and its 2018 sustainability report does not address it. That is despite China’s President Xi Jinping issuing a joint statement with President Emmanuel Macron of France in March 2019 calling for “reorienting public and private investment toward fighting climate change and protecting biodiversity”. The China Development Bank did not reply to inquiries either.

But Halcyon Agri told Global Witness: “Since Halcyon took over management of Sudcam in late 2016, it has been a priority to address the legacy issues we inherited in Cameroon. There is no ‘overnight’ solution to fixing the issues.” The company insisted it had ceased all felling and clearing in Cameroon and established a community forest.

Majority-owned by the government of Singapore, the Olam Group is an agribusiness that attracted massive funding from famous banks during a period when it was accused of widespread clear-cutting in the world’s second largest rainforest. In a December 2016 report, the NGO Mighty Earth calculated that Olam had cleared approximately 20,000 hectares of forest inside its Gabonese oil palm plantations since March 2012. Olam is still operating on this land.

During that time, the company secured a $2.2 billion revolving loan facility. This arrangement was provided by multiple household names in the banking world, including HSBC and Standard Chartered Bank. They were among the Senior Mandated Lead Arrangers of that loan. Global Witness estimates HSBC provided $1.1 billion in loans and $583 million in underwriting services to the company between 2013 and 2019. Standard Chartered, meanwhile, provided an estimated $187 million in underwriting services and $1.16 billion in loans.

In 2017, Olam agreed with Mighty Earth to change its practices and suspend deforestation in Gabon for palm oil and rubber plantations, although both parties said there remained “important issues to resolve.” An Olam spokesman told Global Witness the company is committed to no further expansion until all their plantations achieve full certification with the Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil in 2021. He said Mighty Earth’s report contained factual errors, and that Olam’s palm oil plantations in Gabon were developed on “savannahs, regenerated farmland and degraded logging areas”.

A Standard Chartered spokesman confirmed it had provided financial services to Olam, but said he was unable to share any environmental assessments. All clients were subject to an environmental analysis, he said. The spokesman pointed out that Mighty Earth and Olam released a joint statement in January 2018 stating “significant progress has been made” by Olam.

The Norwegian pension fund dropped Olam from its holdings in 2018 following “assessments of governance and sustainability risks.” HSBC, however, said it was “unable to comment on specific companies, even where there may be information in the public domain”. “This confidentiality extends to our own due diligence,” said a spokesman.

Global Witness also questioned the bank on its Agricultural Commodities Policy, and whether it had disclosed the names of any palm oil clients since adopting this in 2017, as per the framework. The policy reads: “New customers are required to consent, before financial services are provided, to HSBC being able to disclose publicly whether the customer is or was a customer of the bank.” The spokesman said: “HSBC’s requirement to be able to disclose publicly whether we bank a specific new (palm) oil customer does not extend to an annual, or other periodic declaration of all new palm oil customers.”

Pressed further on whether the bank had published the name of a single new customer, he made no comment. However, the spokesman said HSBC was one of the first banks to introduce a forests policy, in 2004, and had “long recognized that development in forest areas can have a major impact on the environment.” The bank says it requires all palm oil clients to be certified sustainable. There is an apparent contradiction between HSBC saying it requires all palm oil clients to be certified sustainable and its client Olam aiming to achieve RSPO certification by 2021.

A spokesman for the Singaporean Ministry of Finance said its holding company’s mandate was to deliver “sustainable value over the long term” and added: “Investment decisions are the responsibility of its board and management, and independent of the Government.”

Our analysis reveals that five of the world’s leading investment banks have held or facilitated key investments in forest-risk companies. JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley and Barclays were all financing companies linked to extensive deforestation.Investment banks play an important role in the financial system, helping companies issue shares or bonds, which they also underwrite. This underwriting provides companies and investors with a crucial guarantee that finance raised will meet a specified target, with the investment banks taking up any excess. Investment banks also provide a wide range of services including managing assets for investment funds, high net worth individuals and pension funds.Goldman Sachs has held over $4.5 million worth of shares in controversial Brazilian beef producer JBS, as well as a small number of shares in the beef producer Marfrig, between 2018- 2019. JBS has repeatedly bought cattle from deforested land. The bank did not reply to repeated emails from Global Witness.

JPMorgan Chase was the underwriter for a $150 million bond issuance by agri-business giant Olam in September 2016, just three months before Olam was accused of destroying approximately 20,000 hectares of rainforest in Gabon. The bank was seemingly undeterred by these revelations, underwriting another $50 million bond issuance the following year. A spokesman told Global Witness the bank “can’t comment on specific client relationships” but said it was “using our resources and expertise to support the transition to a lower carbon future”.

Bank of America underwrote bond issuances worth an estimated $498 million for the Brazilian beef trader Minerva since 2014, as well as providing over $50 million in loans to Marfrig. It did not respond to repeated queries from Global Witness.

Morgan Stanley underwrote a series of bond issuances worth an estimated $947 million for Brazilian beef trader Marfrig between 2014 and 2017. A spokeswoman conceded it had financed Marfrig, but noted the bank had not done so in 2018 or 2019. She insisted deforestation risks are analyzed carefully.

Barclays, which has a major investment banking division, was a Mandated Lead Arranger of a $2.2 billion revolving loan facility that Olam secured in 2014. In a report released in December 2016, the NGO Mighty Earth calculated Olam had deforested approximately 20,000 hectares of forest inside its Gabonese oil palm plantations since March 2012. A spokesman told Global Witness the bank was unable to share outcomes of its due diligence process “for confidentiality reasons”. He said the bank applied “stringent environmental and social impact assessment policies”.

All these banks have some kind of policy statement acknowledging and mitigating the risk that their financing can fuel deforestation. These focus predominantly on the risk of deforestation posed by the timber industry and in some cases palm oil.

New Guinea

The world’s third-largest rainforest extends across the island of New Guinea, from Indonesian-controlled West Papua into Papua New Guinea. This forest directly supports the livelihoods of rural Papua New Guineans. Although almost all land in Papua New Guinea is legally controlled by indigenous groups, agricultural projects including palm oil have co-opted millions of hectares of land and forests, with grave results for community lives and livelihoods.

The Papua New Guinean government plans to have 1.5 million hectares of plantations by 2030, and a 2016 study commissioned by the World Bank identified the expansion of oil palm as the most significant threat to Papua New Guinea’s forest cover.

The Rimbunan Hijau Group (RHG, ‘Forever Green’ in Malay) is a Malaysian conglomerate with palm oil operations on tens of thousands of hectares in Papua New Guinea. Global Witness has previously documented the controversy surrounding these operations, which includes credible allegations of fraud and forgery perpetrated at the expense of indigenous landowners. Rimbunan Hijau has consistently denied this, claiming local communities support the project and the company has not broken any laws.

Since 2008, RHG has deforested more than 20,000 hectares at its plantations in the province of East New Britain, with the intention of planting an eventual 31,000 hectares of oil palm. The group’s financiers include the office of Sarawak’s State Financial Secretary of Malaysia, which held shares in the group worth over $6 million as of March 2018, and the Malaysian Affin Bank, which provided over $33 million in loans in the time-frame studied. Neither institution has any public deforestation policy nor responded when contacted repeatedly by Global Witness.

Global Witness’s own research focused on the world’s three largest rainforests. But other NGOs have looked at the financial sector’s activity in Indonesia, a crown jewel of the world’s tropical forests. Combined, its islands have even more rainforest than New Guinea. According to the Convention of Biological Diversity, these biomes hold 10% of all documented mammals, birds, reptiles and fish species. Its forests are in the top three countries for the carbon its forests stock, the World Resources Institute (WRI) found.But for decades, Indonesia has been a deforestation hotspot. Of the top ten countries estimated by the WRI to have the most extensive canopy cover in 2000, Indonesia lost the highest percentage of its trees up to last year: 16% of the total. The main causes are palm oil plantations and logging, driving almost half of deforestation between 2001 and 2016.This led Indonesia to become the world’s biggest producer of palm oil – and almost all the financing traced by Rainforest Action Network (RAN) comes from Western and Asian banks. The NGO’s analysis found that over the last eight years, the global financial sector pumped $20.9 billion into companies producing palm oil, pulp and paper, rubber and timber in Indonesia.

HSBC bankrolled companies destroying forests for palm oil there, the Environmental Investigation Agency reported. (The bank claimed in response it only financed companies that sourced certified sustainable palm oil.)

And other household names such as Citigroup, Standard Chartered and the Dutch Rabobank were exposed by RAN financing a company linked to human rights violations in the palm oil sector. All three subsequently cancelled loans to the company involved.

For decades now, the financial sector has greased the wheels of the industries turning Indonesia into the global bad boy of deforestation.

According to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, humanity now has eleven years left to avoid the worst effects of climate change. To stand a chance, we need to keep our forests standing. Tropical deforestation alone is currently responsible for about 8% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. That is more than the emissions of the entire European Union, and only just behind the United States.

Yet forests do not need to be destroyed for agribusinesses to plant crops and raise cattle. There is no need to choose between protecting forests and producing food. Farming intensification practices have been shown to increase agricultural production in the tropics while avoiding deforestation. Expanding farming onto degraded land, and reducing the third of all food produced that is lost or wasted, are additional ways to put more food on people’s tables while safeguarding forests.

The investing strategies exposed in this report are cynical and short-sighted. Investments driving climate change present material risks to shareholders. For instance, when the agribusiness United Cacao was delisted by the London Stock Exchange over claims of illegal deforestation, its investors lost $42 million in one quarter. As governments begin regulating against products grown on deforested land, and markets increasingly value commodities produced without deforestation, financiers run the risk of ending up with stranded assets.

Meanwhile, the development of niche green finance products and PR lauding green credentials are fig leaves that fail to address the fundamental problems associated with finance’s bankrolling of environmental destruction.

Instead, those in the financial sector must take responsibility for the impact of their financing and investments on forests, people and the climate. They have a responsibility to the planet and its people, their investors, and future generations, to ensure that they are not fueling deforestation or human rights abuses. Financial sector companies must ensure more rigorous due diligence, strengthen their deforestation policies and commitments, and take meaningful measures to ensure that they implement them effectively.

But self-regulation alone is not enough. Policy makers must address the systemic failure of the financial system, and the companies it finances or invests in, to tackle deforestation and human rights abuses by introducing regulatory measures, including mandatory due diligence, and properly enforcing them. Without urgent action and powerful new laws, the global financial system will only pour fuel on the deforestation wildfires.

Recommendations

Key governmental and private sector commitments on deforestation set targets to achieve by 2020, making it a critical year for forests. All actors must seize the opportunity to renew and strengthen their efforts to tackle deforestation by committing to time-bound action plans, which are independently verifiable and publicly reported to ensure accountability for their delivery.

For government:

- Governments need to regulate the financial sector to stop the financing of, and investment in, deforestation. Regulation should include, among other possible measures, mandatory due diligence requiring investors and the financial sector to identify, prevent and mitigate environmental, social (including human rights) and governance risks and impacts. It should involve standardised disclosure and transparency through regular public reporting on due diligence policies and practices, proportionate penalties to ensure compliance, and complaint mechanisms for third parties and affected individuals.

- Regulatory approaches must also enable forest communities to uphold and defend their rights, and ensure that financial institutions are not profiting from, or handling any proceeds of, forest-related crime and related human rights abuses.

Financiers, investors and others in the financial sector need to:

- Commit to a Deforestation and Land Grab free policy for their financing and investment. This should include a commitment to zero deforestation and zero exploitation, including respecting the principle of Free, Prior and Informed Consent of local communities for all activities affecting them and their rights.

- Undertake due diligence on investments to identify, prevent and assess environmental, social (human rights) and governance risks and impacts, take action on risks identified, monitor and track responses and remedy harms done. This should be particularly rigorous in sectors associated with deforestation e.g. agricultural commodities sourced from countries with tropical rainforests.

- Ensure monitoring, implementation and enforcement of deforestation policies and report in a way that allows independent verification by interested third parties. This should include writing policy compliance into loan contracts with agribusiness customers. A senior corporate representative, such as a board of director at the financial institution should be responsible for the policy’s implementation and financier’s compliance with that policy. This could include engaging with companies to drive positive change, but ultimately being prepared to withhold financing if companies are unable to show that they meet financiers’ policies on deforestation.

- Disclose their exposure to palm oil, soy, timber, beef and other soft commodities associated with deforestation. At minimum, this should include investors publishing all their holdings, lenders making public the name of corporate agribusiness clients as is already accessible to the financial sector via corporate databases, publishing social and environmental impact assessments and ensuring local communities are provided information on financial sector actors and their policies.

- Advocate for regulation to stop the financing of, and investment in, deforestation, including mandatory due diligence regulation to ensure a level playing field and develop standards for due diligence and disclosure.

- Ensure justice for affected communities through meaningful accountability processes.

- All financiers of or investors in JBS, Marfrig and Minerva should initiate an immediate investigation into how the sourcing of cattle through indirect suppliers passed their internal due diligence processes.

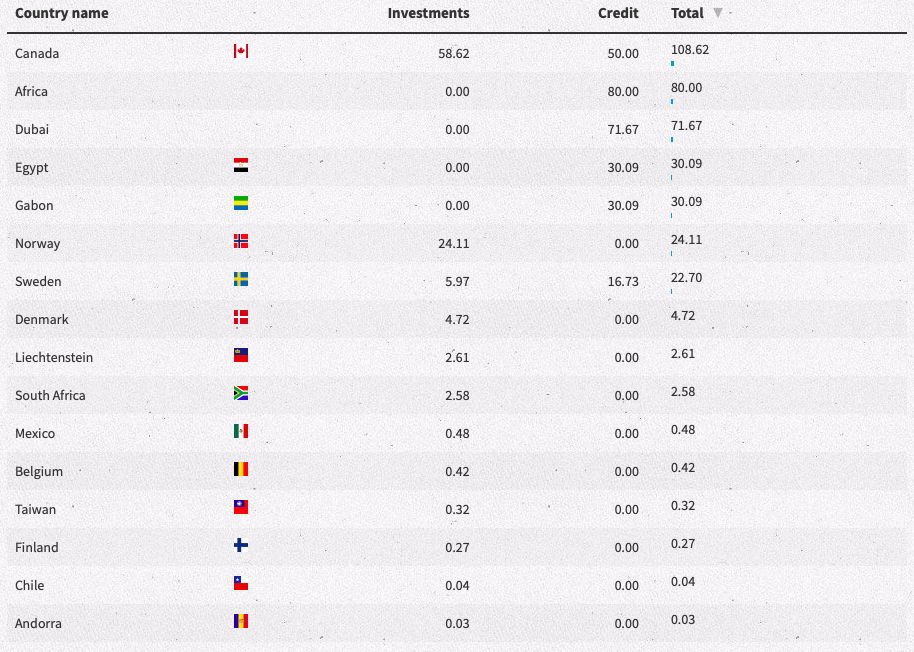

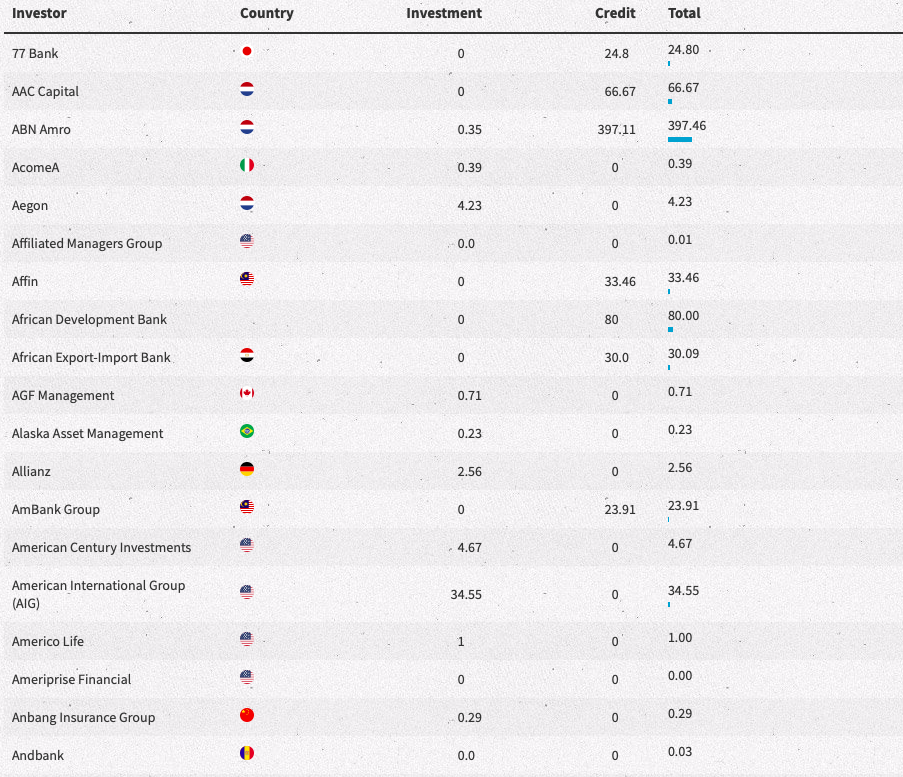

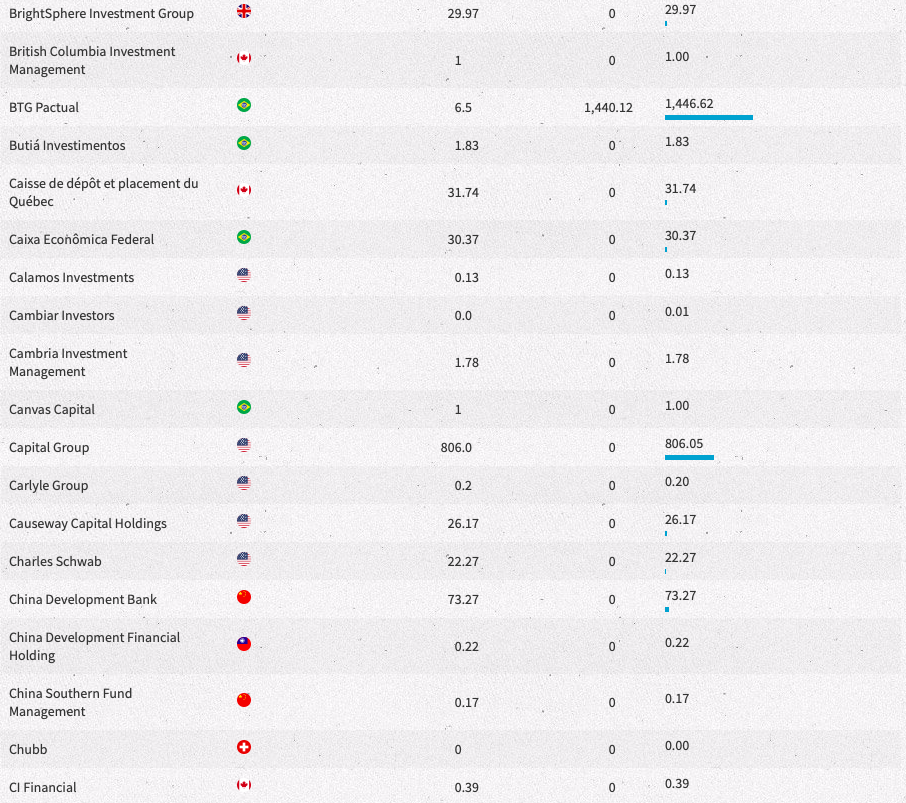

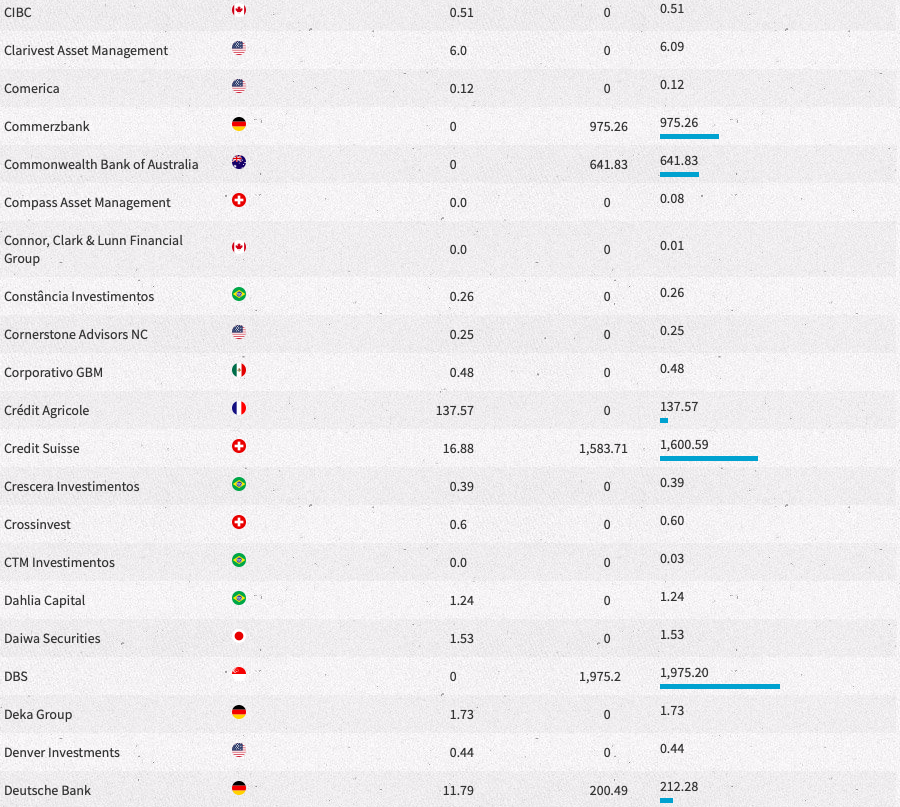

Sources of Finance for Rainforest Destruction

Global Witness commissioned Profundo to research the financing of six agribusinesses active in either Papua New Guinea, the Congo Basin, or the Brazilian Amazon. Credit activities, which include loans and underwriting, were analyzed between January 2013-March 2019, while share and bond-holding was analyzed at their most recent filing date as of April/May 2019. It is impossible to know how much of any given financing, if any, directly funded deforestation. By publishing this data set, we make no claim that any named bank knowingly finances rainforest destruction or is guilty of any specific wrongdoing. However detailed findings about some featured institutions can be found in our accompanying report, Money to Burn. Amounts are given in million USD.

Financial institution financing contributions

The financial databases do not always include details on the levels of individual financial institutions’ contribution to a deal. Individual bank’s contributions to syndicated loans and underwriting were recorded to the largest extent possible where these details were included in the financial databases. In many cases, the total value of a loan or issuance is known, as well as the number of banks that participate in this loan or issuance. However, the amount that each individual bank commits to the loan or issuance has to be estimated. This research uses a two-step method to calculate this amount. The first uses the ratio of an individual institution’s management fee to the management fees received by all institutions. This is calculated as follows:

Participant’s contribution: ((individual participant attributed fee/sum of all participants attributed fee) * principal amount).

When the fee is unknown for one or more participants in a deal, the second method is used, called the ‘bookratio’. The bookratio (see formula below) is used to determine the commitment distribution of bookrunners and other managers. Bookratio: ((number of participants – number of bookrunners)/number of bookrunners).

Table 1 shows the commitment assigned to book runner groups with this estimation method. When the number of total participants in relation to the number of bookrunners increases, the share that is attributed to bookrunners decreases. This prevents very large differences in amounts attributed to bookrunners and other participants.

Table 1 Commitment assigned to bookrunner groups

Bookratio Loans Issuances

>1/3 75% 75%

>2/3 60% 75%

>1.5 40% 75%

>3.0 <40% <75%*

* In case of deals with a bookratio of more than 3.0, we use a formula which gradually lowers the commitment assigned to the bookrunners as the bookratio increases. The formula used for this:

((1/√bookratio)/1.443375673)

The number in the denominator is used to let the formula start at 40% in case of a bookratio of 3.0. As the bookratio increases the formula will go down from 40%. In case of issuances the number in the denominator is 0.769800358.

The Financiers of Rainforest Destruction

Global Witness commissioned Profundo to research the financing of six agribusinesses active in either Papua New Guinea, the Congo Basin, or the Brazilian Amazon. Credit activities, which include loans and underwriting, were analyzed between January 2013-March 2019, while share and bond-holding was analyzed at their most recent filing date as of April/May 2019. It is impossible to know how much of any given financing, if any, directly funded deforestation. By publishing this data set, we make no claim that any named bank knowingly finances rainforest destruction or is guilty of any specific wrongdoing. However detailed findings about some featured institutions can be found in our accompanying report, Money to Burn. Amounts are given in million USD.

Financial institution financing contributions

The financial databases do not always include details on the levels of individual financial institutions’ contribution to a deal. Individual bank’s contributions to syndicated loans and underwriting were recorded to the largest extent possible where these details were included in the financial databases. In many cases, the total value of a loan or issuance is known, as well as the number of banks that participate in this loan or issuance. However, the amount that each individual bank commits to the loan or issuance has to be estimated. This research uses a two-step method to calculate this amount. The first uses the ratio of an individual institution’s management fee to the management fees received by all institutions. This is calculated as follows:

Participant’s contribution: ((individual participant attributed fee/sum of all participants attributed fee) * principal amount).

When the fee is unknown for one or more participants in a deal, the second method is used, called the ‘bookratio’. The bookratio (see formula below) is used to determine the commitment distribution of bookrunners and other managers. Bookratio: ((number of participants – number of bookrunners)/number of bookrunners).

Table 1 shows the commitment assigned to book runner groups with this estimation method. When the number of total participants in relation to the number of bookrunners increases, the share that is attributed to bookrunners decreases. This prevents very large differences in amounts attributed to bookrunners and other participants.

Table 1 Commitment assigned to bookrunner groups

Bookratio Loans Issuances

>1/3 75% 75%

>2/3 60% 75%

>1.5 40% 75%

>3.0 <40% <75%*

* In case of deals with a bookratio of more than 3.0, we use a formula which gradually lowers the commitment assigned to the bookrunners as the bookratio increases. The formula used for this:

((1/√bookratio)/1.443375673)

The number in the denominator is used to let the formula start at 40% in case of a bookratio of 3.0. As the bookratio increases the formula will go down from 40%. In case of issuances the number in the denominator is 0.769800358.