The Mideast’s Place in Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership

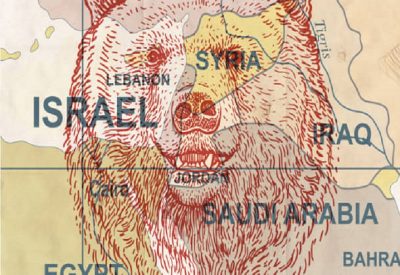

Russia’s Greater Eurasian Partnership envisages the supercontinent peacefully coming together in the shared interests of peace, stability, and development, brought about by Moscow’s “balancing” strategy in recent years which was first practiced in the Mideast region, one of the most important areas of the world for the success of this hemispheric construct.

The Greater Eurasian Partnership

Russian foreign policy and grand strategy more broadly are the subject of heated discussion among experts all across the world, but all observers would do well to accept a few objective facts about its guiding vision when producing analyses about this topic. The Eurasian Great Power is officially pursuing what it calls its Greater Eurasian Partnership, which President Putin described during his keynote speech at the second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing last April as “a project designed to ‘integrate integration frameworks’, and therefore to promote a closer alignment of various bilateral and multilateral integration processes that are currently underway in Eurasia.” In practice, it’s envisaged that this will be advanced by Russia taking advantage of its centrally positioned location in Eurasia to connect the rest of the landmass through creative solutions that leverage its classical and military diplomacy.

Russia’s Syrian-Centric Strategy

To explain, Russia is currently implementing a “balancing” act in Eurasia whereby it seeks to establish equally excellent relations with various pairs of rival states, especially those that are its non-traditional partners, so that peace, stability, and development can come to define the landmass’ future. In the Mideast context, this relates to the GCC & Iran, the GCC & Turkey, Turkey & Syria, Turkey & “Israel”, “Israel” & Syria, and “Israel” & Iran. This ambitious goal is made possible by the many strategic opportunities that opened up in the region after Russia’s 2015 military intervention in Syria. Instead of taking a partisan approach to the conflict like many had expected it would do, the Russian Aerospace Forces concentrated their attacks on the armed anti-government fighters that both Moscow and Damascus regarded as terrorists, with Russia generally eschewing attacks against groups that it didn’t believe deserved this designation despite Syria sometimes holding a different view about them.

This “balanced” approach served Russia’s security interests while also enabling it to earn credibility with the non-terrorist anti-government opposition, after which Moscow leveraged its diplomatic dominance over the conflict in an attempt to bring both sides together towards an eventual political compromise that it began to invest in following the commencement of the January 2017 Astana peace process. Of crucial significance is Turkey’s participation in that framework alongside Iran’s even though Moscow and Ankara support different sides, which was proof of Russia’s “balancing” intent. Although the Astana meetings haven’t resulted in much of tangible political significance, they nevertheless succeeded in greatly reducing armed conflict in the country through the creation of so-called de-escalation zones, the most important of which is in Idlib. In addition, Russia also declined to directly confront American forces in Northeastern Syria, which proved its moderate intentions.

The “Balancing” Act

Russia’s “balanced” actions in Syria showed the rest of the region that it’s serious about being as neutral of a power broker as possible, a much-needed role to play considering the uncertainty brought about in recent years by the US’ generally unpredictable policy. The goodwill that Russia generated throughout the course of its ongoing military and subsequent diplomatic interventions in Syria is most directly responsible for why it’s nowadays able to proudly enbjoy equally excellent relations with the aforementioned pairs of regional rivals. Proof of this policy in practice rests with President Putin’s numerous interactions with his Turkish, Iranian, and “Israeli” counterparts, as well as his official visits to Saudi Arabia and the UAE last October, which importantly came two years after Saudi King Salman made history by being the first of his country’s monarchs to visit Moscow. None of this would have been possible had Russia not earned its reputation as an honest broker.

This is even more amazing of a diplomatic achievement in light of Russia continuing to sell various arms to some of these same rival pairs of states. Russia used to only sell its wares to Syria and later Iran, but has recently taken to striking deals with Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE too. From the Russian grand strategic perspective, selling weapons to both sides of a regional rivalry isn’t intended to support one against the other, but rather to retain the balance of power between them so as to facilitate political solutions to their problems. It also enables Russia to make important inroads with its new non-traditional partners like the GCC and Turkey by showing that it won’t let its legacy partnerships with Iran and Syria get in the way of improving their bilateral military ties. Once again, it can’t be emphasized enough just how much this overall outcome is the result of Russia’s “balanced” approach after militarily and diplomatically intervening in Syria.

Economic Integration Catalysts

Against the backdrop of Russia’s successful classical and military diplomacy in the Mideast, it’s only natural that it would seek to institutionalize these relationships in an economic framework prior to integrating them all together under a common vision. Therein lies the significance of the free trade agreements that Russia wants to reach with all of its relevant partners under the aegis of the Eurasian Economic Union. It already has an interim arrangement of this nature with Iran and is presently negotiating one with “Israel“, which goes to show how these two foes have at least one common interest in expanding their trade ties with Russia. In the future, it wouldn’t be unforeseeable to expect Russia to open similar negotiations with the GCC, Syria, and Turkey, all with the aim of broadening its newfound regional influence in a mutually — and potentially even multilaterally — beneficial way.

The End Game

The Greater Eurasian Partnership is the umbrella under which these multifaceted initiatives are being organized, but it’s much more than just a vision of supercontinent-wide free trade sometime in the future. That’s an integral component of what Russia is pursuing but definitely not everything since it also has military and political designs as well which would greatly facilitate this eventuality if they ever enter into practice. Concerning the first, Russia proposed a collective security arrangement for the Gulf last year, which while only tepidly received was nevertheless a step in the direction of what Moscow desires to achieve, which is to stabilize this strategic space so as to encourage its members to concentrate on political resolutions to their problems. About those and others in the region such as mutual Syrian-Turkish antagonism, Russia has offered its diplomatic services to mediate between all relevant parties if they ever request the need for it to do so.

The end game is the establishment of its economic vision for Greater Eurasia, but the odds of this happening are vastly improved through the success of its military and political efforts since the latter two would uphold the free trade system that Russia believes would create a complex system of interdependence between all stakeholders. Moscow accepts that disagreements between some countries will likely persist, but it places faith in the belief that each party’s shared interests in peace, stability, and development make its Greater Eurasian Partnership a realistic goal for everyone to pursue. After all, the common political denominator between them all is their equally excellent relations with Russia, the only country apart from perhaps China that can boast of such privileged ties with each party. Unlike the People’s Republic, however, Russia is pursuing more than just economic goals as explained by this article’s analysis of its Greater Eurasian Partnership.

Concluding Thoughts

As it stands, Russia has reasonable enough odds of achieving its strategic vision for the Mideast region. There are still impressive obstacles that would need to be overcome, but they’re not insurmountable. Russia has already succeeded in making itself an indispensable player in regional affairs by virtue of its military and diplomatic dominance over the Syrian conflict, which enabled the country to experiment with its “balancing” strategy that ultimately yielded very real results in the political, economic, military, and strategic spheres thus far. There’s still a lot more work to be done, and it’s unclear what time frame one can talk about when discussing the full implementation of the Greater Eurasian Partnership, but the fact of the matter is that the Mideast is one of the most important areas of the world for this hemispheric construct, so it can accordingly be predicted that Russia will continue to invest its efforts in pursuit of this grand strategic goal across the coming years.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on OneWorld.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from OneWorld