How Mercenaries and Advisers Fight the Wars the UK Won’t Own

Colonial powers haven’t given up military meddling overseas – but they’ve learned how to keep it out of the news.

‘Mercenary’ is an evocative word, conjuring thoughts of adventure in foreign lands and elastic personal ethics, but probably not the bureaucratic calculations of British foreign policy. That is a tribute to the success of governments in keeping their use of private military forces in the shadows.

It’s worth pointing out that even soldiers on the state payroll get involved in dubious work abroad. A year or so after the 2011 upheavals in Tunisia and Egypt I was asked to speak at a conference on Middle East security, held in Dubai. It was not long after disturbances in Bahrain had inspired the security forces of the kingdom’s Sunni leadership to violently repress its Shia majority with the help of Saudi Arabia and the Emirates.

Over coffee one morning I happened to be talking to another participant. As we exchanged small talk he explained that he was there as a British Army officer on secondment to the Saudi army. He was advising them as a communications specialist, not least in operations in Bahrain.

The Bahraini repression of dissent in 2011-12 caused controversy around the world, but the British government – then a Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition – only mildly condemned it and the media in western Gulf states scarcely mentioned it. Behind the scenes, though, UK armed forces personnel were clearly helping the Saudis support the Bahraini government’s repression, just as they have been taken part more recently in Saudi actions in Yemen.

The UK’s resolute support for Bahrain should cause little surprise, given that we have a fully operational naval base there, HMS Juffair, which is currently the home port for four minehunters and an anti-submarine frigate, HMS Montrose. Last year’s Oxford Research Group briefing ‘Confronting Iran: the British Dimension’ showed that Juffair would be a key part of any British involvement in a Trump war with Iran. In a sense, that army officer at the Dubai conference was just the tip of the iceberg.

Like the US and other ex-colonial powers, the UK has for decades given military support to regimes overseas, often extending to the deployment of serving military with local forces, sometimes going right through to direct combat. Any of the popular accounts of post-war British military developments written for enthusiasts will demonstrate this, a fascinating example being Vic Flintham’s comprehensive ‘High Stakes: Britain’s Air Arms in Action 1945-90’ (Pen and Sword, 2009).

Much less recognised is the much more extensive use by states such as the UK of a wide range of mercenary security companies. These operate mostly below the radar, with little detail getting into the public domain, despite their size: The Economist reported in 2012 that the US government had 20,000 private guards in Iraq and Afghanistan alone, while the African Union forces operating in Somalia were trained by a South African company. Sometimes the companies are so large that they may include in their logistics floating arsenals as support bases for state-funded operations such as the anti-piracy operations off the Horn of Africa and Yemen. In this respect the Omega Research Foundation’s studywith Oxford Research Group five years ago was an eye-opener for many.

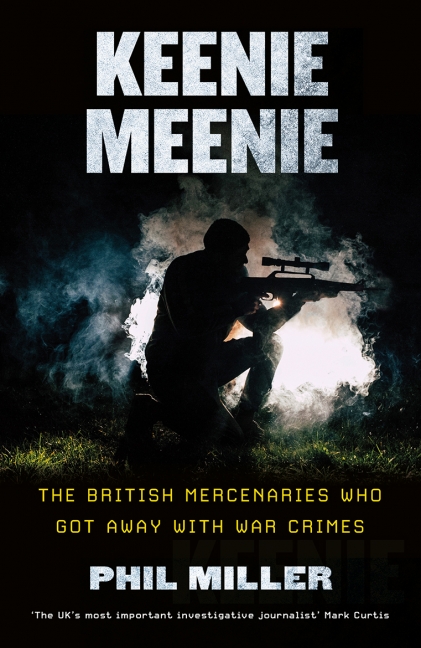

Occasionally we get a really good analysis and one of the best is Phil Miller’s remarkable ‘Keenie Meenie: The British Mercenaries Who Got Away with War Crimes’, published next week by Pluto Press.

Occasionally we get a really good analysis and one of the best is Phil Miller’s remarkable ‘Keenie Meenie: The British Mercenaries Who Got Away with War Crimes’, published next week by Pluto Press.

Keenie Meenie Services operated from 1975 through to the late 1980s before being transformed into Saladin Security, which is still in business today. Its main office is in London’s Kensington, with regional offices in Afghanistan, Iraq, Dubai, Ghana, Kenya and South Sudan, operating in many countries across the world for government and commercial customers.

Miller’s book is primarily concerned with the early Keenie Meenie years, not least the company’s extensive involvement in the terribly violent Sri Lankan civil war, and one of his main points is that mercenary companies, then and now, allow states to intervene in wholly deniable ways. For the UK, as he puts it, “as long as British governments want to intervene militarily in the affairs of other countries, mercenaries will remain an important tool in their arsenals, to be used in the most sensitive circumstances where Parliament, the press and the public would not stomach official British involvement”.

What distinguishes Miller’s book is the depth of research. Investigative reporters often have to rely on personal information from anonymous sources, but Miller has also done extensive documentary research, principally at the National Archives, backed up by frequent recourse to Freedom of Information requests.

Sustained research is essential if one wants credibility in such a controversial area, but the end result of such work, especially if university-based, is often a dry academic treatise that might be very valuable but deter the general reader. This is why Miller’s achievement is so welcome: a book that contains close to 500 references and footnotes yet is thoroughly readable throughout.

So what of his conclusions? Can mercenary activities on behalf of states be made more transparent and accountable? Not if the UK is an example. “Any legislation that reins in private military companies would also have the effect of constraining British foreign policy makers from dabbling in secret wars.” he writes. “And perhaps that is why mercenaries are unlikely to be outlawed any time soon.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Featured image: Sri Lankan refugees, 2005, MM/JRS/Climatalk .in/Flickr. CC BY-NC 2.0. Some rights reserved.