Melting of Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets: Atmospheric CO2 and The Shift of Climate Zones

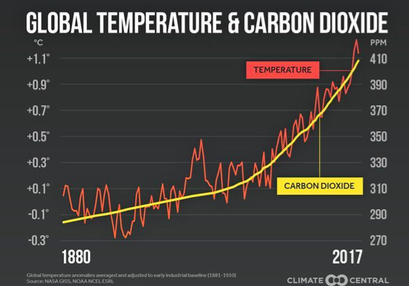

As the concentration of atmospheric CO2 has risen to 408 ppm and the total greenhouse gas level, including methane and nitrous oxide, combine to near 500 parts per million CO2-equivalent, the stability threshold of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, currently melting at an accelerated rate, has been exceeded. The consequent expansion of tropics and the shift of climate zones toward the shrinking poles lead to increasingly warm and dry conditions under which fire storms, currently engulfing large parts of South America (Fig. 1), California, Alaska, Siberia, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Angola, Australia and elsewhere have become a dominant factor in the destruction of terrestrial habitats.

Fig. 1. Sensors on NASA satellites Terra and Aqua captured a record of thousands of points of fire in Brazil in late August. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

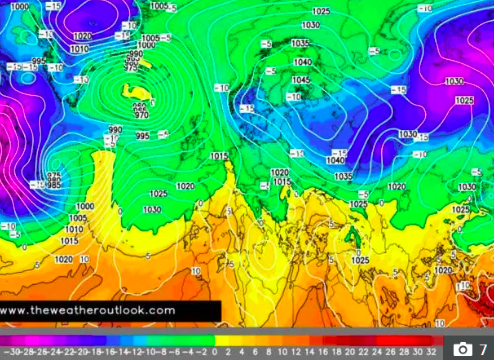

Since the 18th century, combustion of fossil fuels has led to the release of more than 910 billion tons of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) by human activity, raising CO2 to about 408.5 ppm (Fig. 2), as compared to the 280-300 ppm range prior to the onset of the industrial age. By the early-21st century the current CO2 rise rate has reached of 2 to 3 ppm/year.

Fig. 2. Global temperature and carbon dioxide. Climate Central.

Allowing for the transient albedo enhancing effects of sulphur dioxide and other aerosols, mean global temperature has potentially reached ~2.0 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. Current greenhouse gas forcing and global mean temperatures are approaching Miocene-like (5.3-23 million years-ago) composition.

The current carbon dioxide rise rate exceeds the fastest rates estimated for the K-T asteroid impact (66.4 million years-ago) and the PETM (Paleocene-Eocene Temperature Maximum) hyperthermal event (55.9 million years ago) by an order of magnitude (Fig. 3). The current growth rate of atmospheric greenhouse gases, in particular over the last 70 years or so, may appear gradual in our lifetime but it constitutes an extreme event in the recorded history of Earth.

Fig. 3. Cenozoic CO2 and temperature rise rates. Current rise rates of CO2 (2.86 ppm CO2/year) and temperature (0.15-0.20°C per decade since 1975) associated with extreme weather events raise doubt regarding gradual linear climate projections. Instead, chaotic climate conditions may arise from the clash between northward-shifting warm air masses which intersect the weakened undulating Arctic jet stream boundary and freezing polar air fronts penetrating Siberia, North America and Europe.

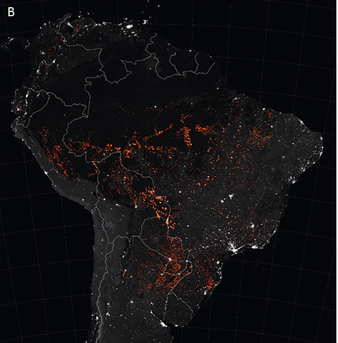

The definition of a “tipping point” in the climate system is a threshold which, once exceeded, can lead to large changes in the state of the system, or where the confluence of individual factors combines into a single stream. The term “tipping element” describes subcontinental-scale subsystems of the Earth system that are susceptible to being forced into a new irreversible state by small perturbations. In so far as a tipping point can be identified in current developments of the climate system, the weakening of the Arctic boundary, indicated by slowing down and increased disturbance of the jet stream heralds a likely tipping point, an example being the recent ‘Beast from the East” freeze in northern Europe and North America (Fig. 4).

A report by the National Academy Press 2011 states:

“As the planet continues to warm, it may be approaching a critical climate threshold beyond which rapid (decadal-scale) and potentially catastrophic changes may occur that are not anticipated.”

Direct evidence for changing climate patterns is provided by the expansion of the tropics and migration of climate zones toward the poles, estimated at a rate of approximately 56-111 km per decade. As the dry subtropical zones shift toward the poles, droughts worsen and overall less rain falls in temperate regions. Poleward shifts in the average tracks of tropical and extratropical cyclones are already happening. This is likely to continue as the tropics expand further. As extratropical cyclones move, they shift rain away from temperate regions that historically rely on winter rainfalls for their agriculture and water supply. Australia is highly vulnerable to expanding tropics as about 60 percent of the continent lies north of 30°S.

Low-lying land areas, including coral islands, delta and low coastal and river valleys would be flooded due to sea level rise to Miocene-like (5.3-23 million years ago) sea levels of approximately 40±15 meters above pre-industrial levels. Accelerated flow of ice melt water flow from ice sheets into the oceans is reducing temperatures over tracts in the North Atlantic and circum-Antarctic oceans. Strong temperature contrasts between cold polar-derived fronts and warm tropical-derived air masses lead to extreme weather events, retarding habitats, in particular over coastal regions. As partial melting of the large ice sheets proceeds the Earth’s climate zones continue to shift polar-ward (Environmental Migration Portal, 2015). This results in an expansion of tropical regions such as existed in the Miocene, reducing the size of polar ice sheets and temperate climate zones.

Fig. 4. The cold fronts penetrating Europe from Siberia and the North Atlantic and North America from the Arctic, 2018. UK Met Office.

According to Berger and Loutre (2002) the effect of high atmospheric greenhouse gas levels would delay the next ice age by tens of thousands of years, during which chaotic tropical to hyper-tropical conditions including extreme weather events would persist over much of the Earth, until atmospheric CO2 and insolation subside. Humans are likely to survive in relatively favorable parts of Earth, such as sub-polar regions and sheltered mountain valleys, where cooler conditions would allow flora and fauna to persist.

To try and avoid a global calamity abrupt reduction in carbon emissions is essential, but since the high level of CO2-equivalent is activating amplifying feedbacks from land and ocean, global attempts to down-draw about of 50 to 100 ppm of CO2 from the atmosphere, using every effective negative emissions, is essential. Such efforts would include streaming air through basalt and serpentine, biochar cultivation, sea weed sequestration, reforestation, sodium hydroxide pipe systems and other methods.

But while $trillions continue to be poured into preparation of future wars, currently no government is involved in any serious attempt at the defense of life on Earth.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Dr Andrew Glikson, Earth and climate scientist, ANU Planetary Science Institute, ANU Climate Change Institute. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.