Martin Luther King: Encountered in Algeria…

Barbara Nimri Aziz Reflects on Martin Luther King Day 2022

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg.

***

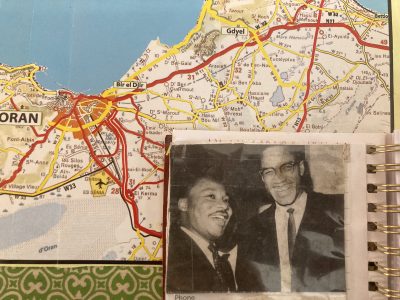

“Mahteen” [Martin], she said, meeting my eyes for the first time while she attended to the papers that I’d set on her desk. I was in Oran, Algeria, being assisted by a clerk in a neighborhood office where I’d come to pay my electricity bill.

She was gazing fondly at the snapshot there of our African American leader. It was the iconic photo of him with Malcolm X taken sometime in the early sixties, before they both left this world.

The woman said nothing else. She asked me nothing about Martin Luther King Jr, nor about the taller man beside him, nor offered her opinion of them.

She would have known Algeria provided succor and inspiration to America’s Black Panther leaders in the 60s. She would have known of Africa’s profound influence on Malik al-Shabazz.

***

On a 2008 visiting professorship in this unattractive but popular seaside city, having rented my own apartment, I had to deal with utility issues myself. My lodging was on Rue d’Hasan ……(a name I’ve since forgotten)– one of Algeria’s tens of thousands of streets, buildings and squares named for martyrs of its painful and costly, never-forgotten and never-recovered-from 1954-1962 war of independence.

I’d placed my daybook on the desk between us as I offered my ID to the woman. Until that remark—the whispered single word, “Mahteen” [Martin]– she hadn’t spoken to me.

Like any underpaid government employee we might encounter anywhere, this lady appeared indifferent to my presence. I had waited in that gloomy place for an hour already and was not in a cheerful mood myself. She made no eye contact with me when I approached her and she seemed uninterested in my visitor status. Algeria is unlike any other Arab place where I’d lived. Here, I had learned to accept the indifference and briskness of Algerians, their caution in public. Some explained this as a lingering aftermath of the decade-long terror war that had ended only seven years earlier.

I said nothing to the clerk as she glanced at my papers. She must be weary of dealing with questions over petty sums and complaints day after day, I thought.

It hadn’t been an easy year for me in Algeria. Relations between the U.S. and Algeria were minimal although cooperative gas exploitation was ongoing. American citizens were advised against visiting here and the U.S. office overseeing my appointment hadn’t laid the groundwork with the university authorities for my stay. If my fellow professors were so unaccommodating, what could I expect from a bureaucrat in a dreary billing office?

This clerk would have known I wasn’t French—few were seen here, although they doubtless lurked behind the scenes and stayed at classy hotels. Other foreigners I occasionally came across were Chinese workers. They kept a low profile. I encountered them only on the train traveling between the capital and Oran as they headed for their outposts.

In the course of my subdued exchange with the clerk, I’d left my daybook open on the desk between us, unconscious of photos exposed on the inside cover. These included a small black and white picture I’d pasted there.

She hadn’t yet looked me in the eye, so when I heard her say “mahteen’, I was puzzled. I looked up to discover her smiling warmly. She looked directly at me, then led my eyes to the open page. “Mahteen”, she repeated.

She was gazing fondly at the snapshot there of our African American leader. It was the iconic photo of him with Malcolm X taken sometime in the early sixties, before they both left this world.

The woman said nothing else. She asked me nothing about Martin Luther King Jr, nor about the taller man beside him, nor offered her opinion of them. She would have known Algeria provided succor and inspiration to America’s Black Panther leaders in the 60s. She would have known of Africa’s profound influence on Malik al-Shabazz.

That whispered name said all that was necessary.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Barbara Nimri Aziz whose anthropological research has focused on the peoples of the Himalayas is the author of the newly published “Yogmaya and Durga Devi: Rebel Women of Nepal”, available on Amazon.

She is a regular contributor to Global Research.

All images in this article are from the author

“Yogmaya and Durga Devi: Rebel Women of Nepal”

By Barbara Nimri Aziz

A century ago Yogmaya and Durga Devi, two women champions of justice, emerged from a remote corner of rural Nepal to offer solutions to their nation’s social and political ills. Then they were forgotten.

Years after their demise, in 1980 veteran anthropologist Barbara Nimri Aziz first uncovered their suppressed histories in her comprehensive and accessible biographies. Revelations from her decade of research led to the resurrection of these women and their entry into contemporary Nepali consciousness.

This book captures the daring political campaigns of these rebel women; at the same time it asks us to acknowledge their impact on contemporary feminist thinking. Like many revolutionaries who were vilified in their lifetimes, we learn about the true nature of these leaders’ intelligence, sacrifices, and vision during an era of social and economic oppression in this part of Asia.

After Nepal moved from absolute monarchy to a fledgling democracy and history re-evaluated these pioneers, Dr. Aziz explores their legacies in this book.

Psychologically provocative and astonishingly moving, “Yogmaya and Durga Devi” is a seminal contribution to women’s history.