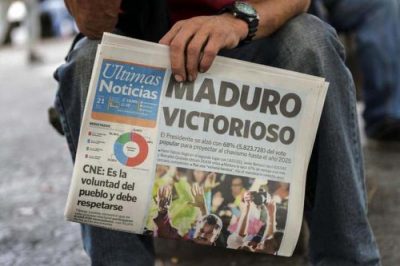

Maduro Wins Another Election, “Fraudulent and Anti-Democratic”, Canada Imposes Economic Sanctions

Labour delegation observes fair, secure election in contrast to Canadian claims of fraud

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was re-elected for a second six-year term in national elections held on May 20. As the candidate of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), Maduro got 67.8% of the vote, while his closest rival, the right-wing Henri Falcón, received 21%. The opposition was divided and some parties boycotted the poll, which may have been a factor in the relatively low voter turnout (for Venezuela) of 46.1%.

However, in lockstep with U.S. policy, the Canadian government denounced the election results as “fraudulent, illegitimate and anti-democratic.” Following the vote, the Department of Global Affairs imposed further economic sanctions on the Maduro government, including against 14 Venezuelan officials Canada claims to be responsible for “the deterioration of democracy in Venezuela.”

Ottawa started sanctioning Venezuela in September 2017 in co-ordination with the Trump administration, imposing an “asset freeze” on the country and “dealings prohibitions” on targeted officials. Forty Venezuelan officials have had their assets in Canada frozen. Canada has also funded the Venezuelan opposition and expelled the country’s diplomats from Ottawa.

Canadians who visited Venezuela to observe the election as part of a labour union delegation, however, do not agree with their government’s policy.

“The Venezuelan electoral process produced a fair election,” says Wayne Milliner, equity officer with the Ontario Secondary School Teachers Federation (OSSTF), who was part of the delegation. “This process is impressive as overseen by the Na- tional Electoral Council (CNE) and demonstrates organization, access to information for voters, security, iden- tification authentication, automation and oversight.

“We also had the opportunity to witness the process after the polls closed and how the electronic vote count is double-checked against the paper ballots in 54% of all polls. Our [Canada’s] election processes are far less sophisticated and we could learn a lot from the CNE.”

Raul Burbano, program director of Common Frontiers, a coalition of Canadian labour unions and non-gov- ernmental organizations, was part of the same observer delegation. He agrees with Milliner, telling me the Venezuelan electoral system is “100% auditable at every stage, including the electoral register, the software and the voting books.” The whole process is presided over by international ob- servers and representatives of each participating political party, he adds.

Burbano also contrasts the real choice he says Venezuelans have at the polls and the one voters have in most Western democracies.

“In Venezuela there is a plurality of political voices and political parties” he says. “Maduro represents a real socialist alternative — the Bolivarian Revolution — which has won presi- dential elections since 1999 and given the people free medical care, free education, land reform, subsidized accommodation and food, as well genuine participatory democracy.”

Maduro’s victory is even more significant, for Burbano,

“because even with the difficult economic situation in Venezuela, caused in large part by the economic embargo [enforced by the U.S. and Canada] and sabotage by the Venezuelan business elite, the majority of Venezuelans still voted for him. This tells you that the Bolivarian movement continues to be the dominant political force in the country. It signals that Venezuelans want to stay the course and continue down the road of alternatives to the corporate neoliberal model.”

Milliner adds that Venezuela is a “post-capitalist system trying to survive in a world that does not want a successful progressive example to exist.” This includes the Canadian government, whose hostility toward Maduro is motivated by the desire to win favour with Washington, which wants to militarily overthrow Maduro. Canada also wants to maintain the neoliberal economic model in Latin America, especially for the benefit of its mining companies, which always saw the rise of progressive governments since 1999 (the “Pink Tide”) as a threat.

Canada currently leads a bloc of 12 mostly Latin American countries called the Lima Group that is op- posed to progressive social change in the Americas, but especially in Venezuela. On May 21, the Lima Group issued a statement condemning the Venezuelan election, discouraging financial institutions from doing business with the Maduro government, downgrading their diplomatic relations and announcing the creation of a high-level meeting of regional immigration officials to discuss the numbers of Venezuelan refugees leaving the country. According to the UNHCR, there has been a 2,000% increase in global asylum applications by Venezuelans since 2014.

Yet, according to Alfred M. Zayas, the UN independent expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order who visited Venezuela in an official capacity in December 2017, it is wrong to define the situation in the country as a “hu- manitarian crisis.” He told Venezuela Analysis in December that while there are shortages of some products, including food products, “the population does not suffer from hunger as for example in many countries of Africa and Asia — or even in the favelas of São Paolo and other urban areas in Brazil and other Latin American countries.”

Milliner drew similar conclusions to Zayas during the delegation to observe the Venezuelan election.

“As a first-time visitor to Venezuela, I expected some of the stories and coverage expressed by the Canadian and American media reflected in what I saw,” he tells me. “Nothing could be further from the truth. I travelled throughout the greater Caracas area and saw middle class and poor neighbourhoods. I saw active construction sites, stores full of produce, fish and meat shops, drug stores with shelves of merchandise, cars on the road and people going to and from work. I saw people living their lives as you would almost anywhere.

“During the entire trip we encountered one person at a stop light asking for money, something I encounter five times every day getting to work in Toronto,” he adds. “This trip reinforced that you should never judge a country or its people by the media.”

Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland has linked her aggressive anti-Maduro rhetoric and Canada’s sanctions to the allegedly deteriorating political and economic crisis in the country, claiming in October,

“This is our neighbourhood. This is our hemisphere. Canadians feel strongly about human rights for people in other countries.”

Yet this concern for human rights and democratic procedures does not seem to extend to the people of other Lima Group member countries with pitiful records in these respects.

Honduras, where Canada backed a military coup in 2009, subsequently suffered under a repressive regime that killed hundreds of environmen- tal activists, human rights defenders and journalists. In November 2017, the regime retained power through an election recognized as fraudulent by independent observers but legitimate by Canada and the U.S.

Nor is Freeland protesting the governments of Brazil and Paraguay, which gained power through legislative coups this year. Or that of Mexico, which stifles labour rights and is substantially responsible for a devastating human rights crisis involving 180,000 homicides and 33,000 disappeared people over the last decade.

“As a Canadian of Latin American origin, I am ashamed of the Justin Trudeau government’s Latin American policy,” says Maria Paez Victor, a Canadian-Venezuelan sociologist and director of the Canadian, Latin American and Caribbean Policy Centre (CALC). “This is a colonial attitude of domination towards Venezuela and Latin America.”

Freeland’s “sadly passé, Cold War mentality and anti-socialist ideology, has thrown Canada into the U.S. adventures of regime change,” says Paez Victor, who points out that while accusing Maduro of being an- ti-democratic, Freeland has refused to let Venezuelan citizens residing in Canada vote in their elections.

“With duplicity and cynicism, Canada disallowed the Venezuelan authorities in Canada to have election stations, alleging they were ‘protect- ing’ Venezuelan democracy!” she says. “George Orwell himself would be astonished at this hypocrisy.”

*

This article was originally published on the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Asad Ismi is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from Granma.