Pakistan-India Crisis: The Machinery of Images and the (Post-)Modern War

On 14 February, 20-year-old Adil Ahmed Dar rammed a vehicle fill of explosives into a bus full of reserve police force personnel in Indian Occupied Kashmir. The attack killed over 40 soldiers and was claimed by militant organization Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM). The response on the Indian side was predictable. Fueled by the hyper-nationalist and sensationalist private media, the Indian government, along with large swathes of the chattering classes, and key opinion makers from across the spectrum, brayed for “decisive action” against “cross-border terrorism” emanating from Pakistan. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan offered a joint-investigation, but sighting Pakistan’s past record in dealing with such cases, India refused the offer and then stepped up its crackdown in Kashmir.

On the night between February 23 and 24, Indian fighter planes intruded into Pakistani territory over the international border for a “surgical strike” (the first time this has happened since the full-scale war in 1971). While the village of Jaba, the target of the “surgical strike,” has a long-standing JeM seminary, Indian planes managed to only frighten some villagers and flatten some trees a kilometer or so away from the alleged “terrorist camp.” The Indian media claimed success for “surgical strike 2.0” (another one had also been claimed by the Indian government in 2016), while the next day, Pakistani air force responded with two Indian planes shot down as part of “a befitting response… at a time and place of its own choosing.” One of the Indian aircraft crashed in Pakistani territory and the pilot Abhinandan Varthaman was captured alive and only mildly injured, immediately becoming the subject of much fascination on the electronic and social media of Pakistan.

Anti-war demonstration in Islamabad: “Yes to Books, No to Bombs.”

Satisfied with having demonstrated Pakistan’s ability to respond, Pakistani PM Imran Khan reiterated the offer of peace and de-escalation from the brink of a disastrous war between the nuclear-armed powers. On the 28th, as a goodwill gesture, Khan announced in Parliament that Wing Commander Varthaman would be released. The move was welcomed by the heads of India’s three armed forces, and after a bout of backdoor diplomacy from the likes of China and the USA, the threat of a disastrous escalation of conflict seems – for now – to be averted. However, the belligerent mood of the Indian media and the Narendra Modi government’s prevarications with regards to further military action (in the context of upcoming general elections), means that things remain uncertain and skirmishes continue to be reported on both sides of the Line of Control in Kashmir.

A Doomed Balance of Forces

While an anatomy of the balance of forces in both countries is not the focus of this piece, some short comments must suffice. This theatrical conflict comes in the wake of fraying hegemony for the Modi government in the face of upcoming elections. Modi’s promise of “vikas” (development) has not materialized, ill-thought out policies such as demonetization to “wipe out” the black economy has hurt the poor, and the BJP-RSS combined have faced defeats in key state elections. In the face of plummeting confidence, the fascist Hindutva combine has resorted to stoking hate attacks against Muslims and Kashmiris in India, a move which proved successful for their election win in the key state of Uttar Pradesh. In the face of these travails, the anti-Pakistan belligerence before the general elections seems quite in accordance with the Hindutva combine’s previous history.

In Pakistan, the ruling classes – and its militarized core – have been facing disarray in the face of political, ideological, and economic challenges. While the political crisis has been temporarily abated with the election of the Khan government, criticism of state excesses – in the form of military operations, extra-judicial killings, and forced disappearances in “peripheral” areas and beyond – have been rife in large swathes of the population. While this has been managed through a mix of coercion, corruption, and wide-spread media censorship, the secular trend has been towards a general decrease in the prestige of the militarized core of the Pakistani state. In such a context, the provocations of Hindutva from across the border have come as a god-send. Of course, nothing promotes one suicidal nationalism as surely as another. And – in a war weary country – with their relatively measured response to Indian aggression, Pakistan’s ruling classes and military have recovered both a measure of coherence and a temporary boost to their legitimacy. Soaring inflation, a looming IMF package, and continuing military operations mean that the shoring up of legitimacy is bound to be temporary.

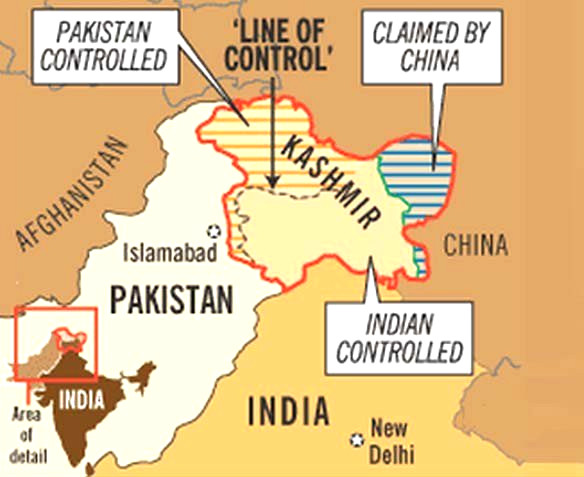

Regardless of the balance of political forces, the two wider realities fueling India-Pakistan conflict remain unchanged. India’s brutal occupation of Kashmir precedes the ascendancy of the RSS-BJP combine and remains the lynchpin of conflict in the region. Indian Kashmir remains the most militarized region of the world with a vibrant independence movement led by the youth. The Indian response has been to grant the military and paramilitary forces wide-ranging and unaccountable powers, with lawyers, human rights defenders, and youth facing the brunt of constant violence (the recent suicide bomber Adil Dar was himself a “guest” of the Indian forces six times in the last two years). This decades-long violence has now been combined with the belligerent rhetoric and regionally expansionist aims of the fascist combine in power in India. In this context, the Kashmiri youths’ resort to spectacular violence – while often counterproductive – is not beyond the realm of the unthinkable.

On the Pakistani side, since the U.S.-sponsored Afghan “jihad” in the 1980s, the security establishment continues to selectively patronize fundamentalist groups as part of their own regional ambitions. These militant groups have wreaked havoc in Pakistan in the aftermath of the War on Terror, with thousands killed and injured, and the “peripheral” areas bearing the brunt of the cycle of militancy, military operations, and drone attacks. Unaccountable security policies and a fraying social contract keeps providing grist to these groups’ violence within Pakistan and in the wider region. In addition to being nuclear powers, both countries remain major buyers of “conventional” weapons: Pakistan is now the world’s leading buyer of Chinese weapons and India was Israel’s largest arms client in 2017.

The Machinery of Images

What should concern pro-peace and democratic forces on both sides of the Radcliffe Line is the use of new media technologies in fueling the latest rounds of conflict and aggression between India Pakistan. For some time now, commentators have been pointing to the dangers and pitfalls of new media technologies – such as private TV channels, WhatsApp, Twitter etc. – and their contribution to the enabling conditions of neo-fascism in India, Pakistan, and beyond: the braying for war, the instantaneous assembly of lynch mobs, the 24/7 cycle of statements and counter-statements, and the manipulation of passions through the accumulation of TRP ratings.

An important aspect to think about here is the changed nature of subjectivity these developments represent. Television and its pocket-size upgrade, the touch screen, is a curious form in which to receive information. Compared to other classically modern media and forms of communication (such as the novel, radio and newspaper), the television and the touch screen herald a qualitatively new dimension of experience: the complete flattening out of time and space, the cancellation of context, the elimination of depth, and the conversion of the audience to mere passive receptacles for the reception of images.

In the rise of television, private media and the touch screen, the character of post-modern forms of the commodity and hyper-mobile capital is more pronounced than ever: the constant cycle of news, the permanent stimuli of the senses, the ever spiraling bombardment of histrionics disguised as opinions, very much akin to the (seemingly) disembodied, self-sustaining, and constantly shape-shifting drive of neoliberal capitalism itself (which of course is the driver of this media proliferation).

Here, the fetish character of (post-)modernity is stamped even more intensely than ever on the machines of our mutual destruction, which rule our consciousness as a fetish endowed with a life of their own. It is the peculiar quality of images that they have no depth, only surface; they represent a freezing and rupture of/from time, and thus project an aura of both confinement to the present and, paradoxically, of being beyond time and history itself. Thus, in the era of postmodernity and its intensified fetish of the commodity, the machine and its image, there is no depth to perception, the experience has no past and no future, it lives on in the momentary stimulus of the senses, the perverse orgasm of the present.

But also, as images curiously flattened out, without history or depth, they turn into mere ruses for filling up with our favourite fantasies of destruction and domination: the death cult of Hindutva versus the Two Nation theory; the cry of Ram and Vishnu on one side versus the slogans of Allah and Haider-e-Karrar on the other. To have one of “our side” killed today, only to “respond fittingly” with two of “their side” killed the next day.

In a now famous essay on The Origins of Postmodernity, Perry Anderson characterized the transition from modernist to post-modernist art as one of a shift “from the images of machinery to the machinery of images.” In Pakistan and India, with our worship of the machinery of war and the fetish rule of the image, we have a peculiar combination of the two.

It is a strange spectacle: the curious amalgamation of the modernist élan of the machine with the postmodernist fetish and flattening out of its image. A very concrete expression of our peculiar dilemma of combined and uneven development: great poverty on one side, dazzling affluence on the other; the conditions of 19th century Europe and of 21st century North America side by side; enclaves of the First World amidst an ocean of the Third World; disembodied “development” in the midst of proliferating zones of exception and exclusion; the plebianization of language and the abundance of WhatsApp; a war fought in places far way and in the intimate spaces of Facebook groups and Twitter feeds. In the words of the great Eric Hobsbawm, “civilization works its miracles and civilized man is turned back almost into a savage.”

This here then – both in this war of images and beyond it – is the challenge of postmodernity for us today. Subjectivity fractured, perception overloaded, senses overstimulated, attention spans ephemeral, memory both constantly created and erased, wars easier to begin than to end. Things falling apart where the center cannot hold, the old certainties of the political subject dissolved within the hyper-mobility and ephemerality of capital itself. All that is solid truly does melts into air.

How to forge a new (revolutionary) subjectivity in these conditions? How to think historically in conditions which militate against historicity? How to add depth to thought and practice, when experience itself has been flattened out? What substrate of experience and forms of organization to anchor the new political subject of emancipation?

How to embody the depravations of war when it is turned into a disembodied video-game on our touch screens? How to forge brotherhood and solidarity across (post-)colonial lines on the map, when the shared heritage of the past is denied by the very workings of commodity society, its machinery of images, and its flattening out of space and time?

The Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) in Pakistan have demonstrated that a unifying experience of the depravations of war can potentially form basis for a mass, anti-war movement with the use of new media technologies. However, as with any social movement in an era of such disarray, questions of ideological and organizational coherence, of sustainability, and of social-spatial alliances with other oppressed social groups in Pakistan remain paramount. That the question of subjectivity has gained increased salience in the context of material changes is without doubt. In case of Pakistan, the PTM – an accounting of all its pitfalls and substantial successes – is an interesting case study for revolutionaries.

With the vagaries of the commodity form and mediatized forms of subjectivity, merely shouting out truth from the rooftops is not enough, when the very grounds of truth and verification have slipped from beneath our feet. Part of the answer must be in the organization of an alternative, determined social force against the battering ram of the commodity form. The other parts of the answer are a matter of both thought and practice.

Otherwise, the old exhortation by the ever-green Rosa remains relevant: class struggle or death, bloody struggle or extinction, Socialism or Barbarism, thus is the question inexorably put.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.