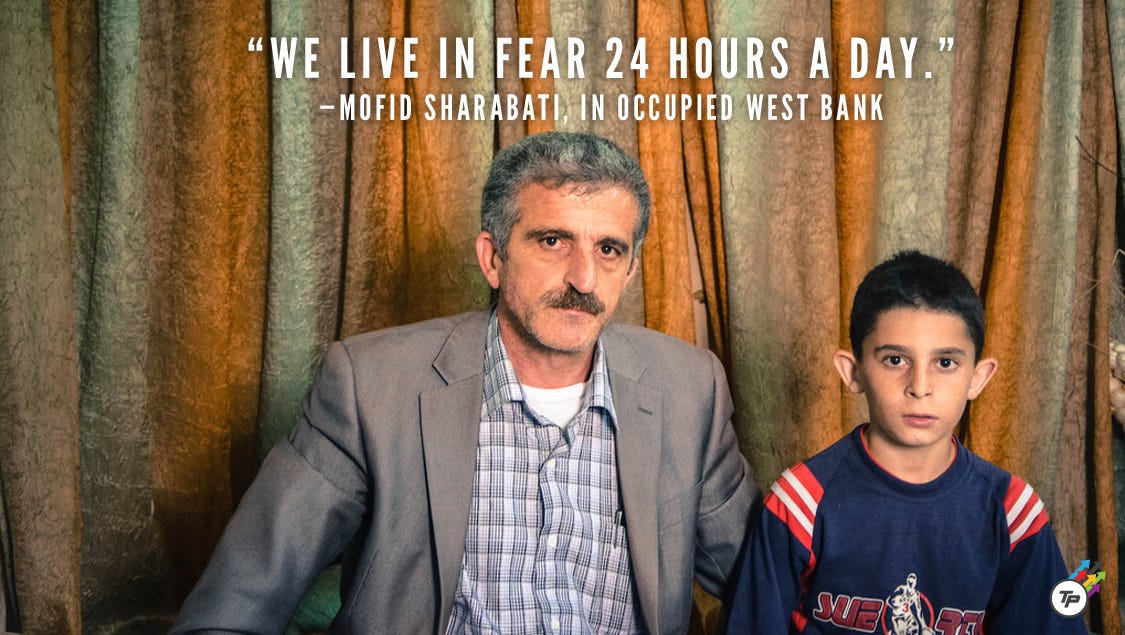

Living In Fear: One Palestinian Family’s Struggle to Survive in the Occupied West Bank

HEBRON, OCCUPIED WEST BANK — Mofid Sharabati shifted uncomfortably on the edge of his bed, having offered all other available seats to the cadre of journalists sprawled across his tiny living room. He waited patiently while his company ate shawarma wraps, still warm after being hand-delivered from a local establishment up the road. He eyed his 10-year-old son Marwan paternally as he dashed back and forth, tiny hands diligently disposing of tin foil and used food wrappers as people finished their meals.

After a few moments, one of the journalists asked Sharabati to describe life in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

We live in fear 24 hours a day.

“We live in fear 24 hours a day,” he immediately said, speaking through a translator. Marwan, now sitting next to him, nodded in agreement. He stared at his feet, fidgeting with the ends of his oversized basketball jersey.

The room of journalists sat quietly for a second, unsure of what to ask next.

Sharabati and his family live in Hebron, the largest city in the occupied West Bank and home to around 200,000 Palestinians. I visited Sharabati’s tiny second-story apartment in mid-October as part of a delegation of journalists traveling with the Foundation for Middle East Peace, a left-of-center organization based in Washington, D.C. that seeks a “just resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” through advocacy and education efforts — including highlighting the Palestinian cause.

A journalist holds aloft a sound bomb, used to disperse demonstrators in Hebron. CREDIT: Jack jenkins

Our trip coincided with a rash of violence that has raged across Israel-Palestine over the past two months, resulting in the deaths of 11 Israelis and more than 58 Palestinians, according to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Much has been written about the various causes of the fighting, during which Palestinians are frequently shot dead, often after attacking Israeli soldiers and citizens, usually with knives. Some argue the attackers, many of whom are teenagers or even children, are inspired by anti-Israeli messages shared on social media, or religious militants such as ISIS who have endorsed the stabbings. Others — including many of the attackers themselves — say they are responding to perceived efforts by Jewish activistsand the Israeli government to erode Muslim control of the Al-Aqsa mosque in East Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam.

But as analysts furiously debate the immediate catalyst for the attacks, there has been less focus on another factor that — while perhaps not the spark that lit the latest blaze — undoubtedly created the conditions for tension in the first place: Israel’s longstanding occupation of the West Bank territories, including the construction of settlements the United Nations deems illegal and whose legitimacy the United States government rejects.

Sharabati and his family offered me a glimpse into life under this occupation, detailing the trials endured by many Palestinians who are all too often literally caught in the crossfire. ThinkProgress could not independently verify all aspects of Sharabati’s story, but his account closely matches numerous reports of Palestinian life published by groups like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem.

The checkpoint

Even within the notoriously tense West Bank, Hebron is a uniquely combustible city. Located roughly 45 minutes south of Jerusalem, violence between Israelis and Palestinians has erupted numerous times over the years — even before the the establishment of the state of Israel. Locals say this is largely due to the presence of Israeli settlements, which are considered invasive by Palestinians but vociferously defended by Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the settlers themselves, who insist they have every right to be there. Clashes between the two camps have been recurrent, including the horrific slaughter of 67 Jewish civilians in 1929, after which most Jews abandoned Hebron for several years. When settlers returned in 1967, nets were installedin the town’s Old City to keep Israeli settlers from tossing stones and garbage onto Palestinians as they passed below.

Things reached a breaking point in 1994, when an American-born Israeli settler massacred 29 Muslim worshippers at a shrine known to Jews as the Tomb of the Patriarchs and to Muslims as the Ibrahimi Mosque. The increasingly volatile situation was then addressed in 1997, when officials signed an agreement to partition the city into two sections: “H1,” to be controlled by the Palestinian Authority (PA), and “H2,” to be controlled by Israel.

A checkpoint in Hebron. CREDIT: Jack jenkins

The imperfect results were on full display just down the street from Sharabati’s home, where a checkpoint divides a Palestinian-controlled section of the city from an Israeli-controlled area. Sharabati and his brother greeted me and other journalists on the Palestinian side of the heavily-armed barrier, surrounded by curiosity seekers who stopped to observe the arrival of yet another group of journalists. Hundreds of Hebron residents strolled past as we exited our vehicle, chattering in Arabic while shopping and eating in the heart of the thriving city.

Yet the crowds steered clear of the nearby concrete blocks that marked the entrance to the checkpoint. Israeli sound bombs and empty tear gas canisters littered the pavement in front of a looming, fence-covered military installation, the refuse of efforts by IDF soldiers to dispel various protests that have sprung up during the recent unrest.

At the direction of our guide, we passed through the checkpoint one at time, a standard procedure made all the more unsettling in the wake of recent stabbings. A trio of heavily armed IDF soldiers greeted us on the other side, weapons out, as a fourth watched us from above. After they let us pass, an eerily deserted street opened up before us, a far cry from the teaming masses we left behind a few moments before.

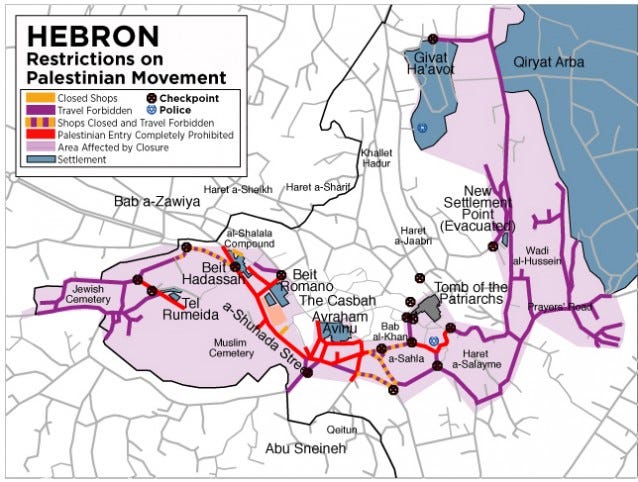

As our party walked down the empty Shuhada Street towards Sharabati’s abode — flanked all the while by two soldiers — the translator explained that the emptiness was due to the city’s bizarre system of subdivisions, where various roads and sections are restricted to Palestinians. Sharabati and his children, for instance, live on the Israeli side of the checkpoint, where only Palestinians with homes can enter if they have explicit permission from the Israeli army. Other areas ban Palestinian businesses, and some forbid them from even walking down the street.

A former IDF member — speaking as part of Breaking the Silence, an organization that collects testimonies of ex-soldiers — would later tell me that the military has a name for these roads: “sterile streets.”

CREDIT: Source: B’Tselem

The draconian measures are justified by the Israeli government as necessary to ensure security; Sharabati and other Palestinian Hebron residents have few, if any, options for protest. Although their land is occupied by the Israeli government, the Palestinians living in the West Bank are not citizens of Israel, and the residents living anywhere other than East Jerusalem are not afforded the ability to apply for citizenship — even if they marry an Israeli. Instead, they are subject to an entirely different legal system: Palestinians operate under military law, where many rights and privileges standard for an Israeli — such as seeing a judge within 24 hours of being arrested — are not guaranteed. Although they can vote for leaders of the PA, they cannot vote in elections for the Israeli government, which ultimately controls many facets of their daily life.

Most Palestinians who used to live on Sharabati’s street have abandoned their homes, citing harassment from Israeli settlers and soldiers. Sharabati made similar claims, noting that sometimes soldiers “throw rocks at us.”

Yet despite these difficulties, he refuses to move.

“This has been my family’s home for 150 years,” he said, defiantly.

Punished for bearing witness

The decision to stay in their ancestral home in Hebron has not made life easy for Sharabati, or the others who live in his house. Every member of his family could recount troubling run-ins with authorities and nearby settlers. Sharabati handed journalists x-rays of his back, showing a series of pins used to repair his broken spine after he reportedly tried to defend his home from an invasion of settlers and members of the IDF. His brother’s visibly injured eye, he said, was misshapen during the same altercation.

Even his son Marwan, who struggled to reach the hat rack to put away a scarf during our visit, was reportedly detained by police in October for several hours. His alleged crime: holding a stone.

A barrier pierced by bullets used to kill a Palestinian woman in late September. CREDIT: Jack Jenkins

When the family isn’t the victim of violence, it is often a witness to it.

At least three different Palestinians were gunned down near their home during the recent surge of knife attacks, all of which showcase longstanding tensions among area groups. One occurred in a neighboring section of the city on October 17, when an Israeli soldier opened fire after being stabbed by 18-year-old Palestinian Tarek Ziad Natsha. The local settler population reportedly blocked the ambulance tasked with carrying the wounded attacker to the hospital, but were eventually dispersed by police, according to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz. Natsha died in the hospital. The soldier survived.

Meanwhile, two other shooting incidents near Sharabati’s home are being investigated as examples of unnecessary use of force. The first occurred on September 22, when a woman named Hadeel al-Hashlamoun was shot and killed by soldiers for allegedly threatening them with a knife. At least two bystanders disputed this account, and many pointed out that she was behind a barricade when they opened fire. Bullet holes from the encounter — clearly piercing through the barrier — are still visible when passing through the checkpoint, raising questions as to whether she presented an imminent threat. A report from Amnesty International has since declared her death unnecessary, classifying it as an “extrajudicial execution.”

Fadel Mohammed al-Qawasameh’s blood still stains the street outside Sharabati’s home. CREDIT: Jack Jenkins

It was the second shooting in less than a month, however, that left a lasting impression on the Sharabati family. On October 17, Fadel Mohammed al-Qawasameh, an 18-year-old resident of Hebron, was gunned down by an Israeli settler immediately outside the family’s house, again for allegedly trying to stab someone. But as the boy lay dying, a video was shot from Sharabati’s window that appears to show officials placing something next to the dying body. Local Palestinians cited this as proof that the soldiers planted evidence, and the clip quickly went viral.

The response from the IDF was swift. When the military learned of the tape, Sharabati said they raided his home, a common occurrence for Palestinians living under military rule. He said they then confiscated his camera and laptop, broke them, and arrested his brother — supposedly for emailing the video to others.

“This is the life we live every day,” he said. “We live in fear they could come back into our home at any time. There is always someone awake.”

Meanwhile, al-Qawasameh’s blood still stains the pavement just feet from the family’s doorstep. They walk by it every day.

Senior Religion Reporter at ThinkProgress. Player of harmonica and ukulele. Tips: [email protected]