Liberated Aleppo: Dying To Get Back to School, or “Back in Government Hands”. Silly BBC Report

“Back in government hands”; the journalist repeated it twice in the same account of her report from Homs, Syria. Lyse Doucet had returned to the former rebel-occupied (and we know the reputation of those rebel jihadis, don’t we?) Syrian city of Homs last week.

(http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-39439757)

With apparent sympathy, Doucet sought out Bara’aa, now 12, to learn how the girl was managing. It had been three years after their first encounter, following the death of the child’s mother in a bombing.

Doucet, considered an outstanding, fearless and compassionate war journalist working across the region today, seemed touched that the child was doing well, especially pleased to be back in school. Doucet omitted any reference to the high value Syrians, like Iraqis and Palestinians among others, place on education. These are nations where every child since the 1960s was educated, where gender parity in school was standard decades ago.

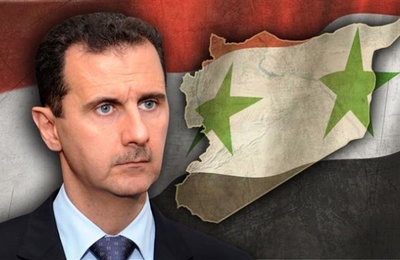

Apart from the silliness of asking an Arab child, any child, if she likes school, and remarking “You don’t have bad memories, do you?”, Doucet seemed incapable of uttering the word ‘liberate’ at any point in her report. Palmyra was not liberated, nor Aleppo, nor Homs. No, they were simply (maybe regrettably, to some) “back in government hands”.

I don’t know if the BBC instructs its journalists never to use the word ‘liberate’ when an enemy army (in this case the Syrian government) regains territory from rebels and terrorist occupiers. Or if Doucet herself simply cannot conceive that ‘liberation’ is what may allow the child’s return to school, indeed the reporter’s own ability to enter Homs at all.

This attitude to Homs is more ironic when not far to the east, American forces are desperately trying to help Iraqis bring Mosul “back into government hands”. In the course of this assault, we are learning, many hundreds of Iraqis—probably including girls and boys like our Homs’ schoolchild—died… to get back to school. When that happens, and everyone prays it will be soon, there will doubtless be celebrations over the ‘liberation’ of Mosul.

Remember all the fanfare surrounding American forces’ attempt to liberate Falluja (in restless Anbar province) in west Iraq in 2004? Many details of the battle, which not only failed but resulted in huge losses of life, were leaked—the US troops used phosphorous gas, and besieged the city trapping many thousands of residents.

(http://www.antiwar.com/orig/jamail.php?articleid=2303)

The event is also remembered because dozens of American troops were killed in that effort, a major battle marking the first American encounter with Al-Qaeda/ISIS insurgents.

(http://dahrjamail.net/an-eyewitness-account-of-fallujah)

(The second battle of Fallujah nine months later is descried as a “coalition victory”; never mind what remains of the city.)

There have been a series of military confrontations in Afghanistan and in Iraq over the years where territory held by U.S. and U.K. troops or their surrogates—were reoccupied by opposing forces. Just days ago a district where 100 British troops had lost their lives “fell to rebels”.

(https://www.rt.com/uk/382029-taliban-capture-sangin-afghanistan/)

Given the considerable number of failures by Americans and their allies to permanently restore rebel-held regions to government hands, one can only admire a government that achieves this. (Although there is no certainty that Homs is really secure. We saw Palmyra in east Syria retaken by ISIS, then again liberated by Syrian forces.)

Consider, if American and British deaths to liberate territory in those distant places are so well remembered, can we not begin to imagine the cost in Syrian military lives? Why, when we heap applause on U.S. veterans, wounded or not, do we have no concept for their Syrian counterparts. How many Syrian mothers and fathers, sisters, brothers, nephews and nieces, grandsons and sons mourn their lost fighters, pray daily for their safety, and may occasionally even celebrate their ability, somehow, to liberate Syrian territory from jihadists?

Anyone in touch with a household in Syria will know the anxiety of family worrying when their son or brother will be called. Any young man, who for one reason or another hasn’t yet been recruited, waits in fear. He has friends who’ve been called up, others who’ve fallen on the battle field. Many refugees are youths who managed to escape the country and military service. Others still enrolled in school, are not exempt.

With every “back in government hands”, or “retaken by rebels”, there is unarguably a heavy toll involved in sending one little girl back to school. We owe her the right to feel her home has been liberated.