The Gulf Monarchies Intervention in The Horn of Africa: Devastating Impact on Somalia

On Saturday morning December 28th, a truck bomb exploded at a busy intersection at KM 5 + security checkpoint at in Somalia’s capital, killing at least 90 people including many University students on their way to Universities outside the capital city, Hawkers, women and children authorities said. It was the worst attack in Mogadishu in more than two years, and witnesses said the force of the blast reminded them of the devastating 2017 bombing that killed hundreds, over 500 dead.

President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, PM Hassan Khaire and the entire Somali Federal Government condemned the attack as “heinous” but did not mention the likely culprit, the al-Shabab extremist group, by name.

But The Somali leadership and Public suddenly suspected and blamed this heinous vicious, immoral, genocidal terrorist act on UAE and Saudi and their Al-shabab islamist praxis’s for destroying the stability and developmental progress. In turn, the terrorist activities of Al shabab, [sponsored by foreign governments] are highlighted with a view to defaming in the eyes of world opinion (as well as estabilizing) the current pro-nationalist Somali federal government of President Farmajoo.

Al-Shabab was blamed for the truck bombing in Mogadishu in October 2017 that killed more than 500 people. The group never claimed responsibility for the blast that led to widespread public outrage. Some analysts said al-Shabab didn’t dare claim credit as its strategy of trying to sway public opinion by exposing government weakness had badly backfired.

This explosion is similar to the one in October2017 and thus, Security and intelligence people suspected that this blast like the one in 2017 is more sophisticated and deadlier and thus, it couldn’t have been a locallyimprovised explosive device(IED) by Al Shabab.

Historical Background

Historically, Gulf (khaleejis)(Saudi a, Emirates and Qatar) countries had culturally, commercial , social and religious inter-relations with Somalia and the peoples of the Horn of Africa from time immemorial

From early maritime seafaring and trading includes various stages of Somali navigational technology, shipbuilding and design, as well as the history of the Somali port cities. It also covers the historical sea routes taken by Somali sailors which sustained the commercial enterprises of the historical Somali kingdoms and empires, in addition to the contemporary maritime culture of Somalia.”[1]

Khaleeji Interventions in Post- Soviet Somalia. 1991-2015

From 1991 Gulf sheikhdoms were only interested in establishing war-torn Somalia as a commercial & maritime gateway and markets for their sub-standard products which dominated the whole business and commercial enterprises of Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan.

For decades, the Gulf States (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, and Qatar) have been buyers, rather than suppliers, of security. Relying on outside protection, they persistently avoided the use of military means. Two analysts used the term “quiet diplomacy” to describe the external policies of Saudi Arabia and the UAE during the pre-Arab spring period.

Oil and Islam have been the main leverage used by the Saudis since the 1960s, while foreign aid and personal networks were the basic policy tools of the Emiratis. Both countries were characterized by low-profile initiatives and the behind-the-scenes negotiations with their regional partners that aimed at promoting amicable relations and guaranteeing the peaceful settlement of disputes.[6] However, until very recently the Horn of Africa was a rather low priority in the foreign policies of both states of the Gulf.

Much of the Gulf’s current interest in the Horn is related to competition with Iran. The election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 led to increased Iranian activity in the Horn of Africa that included an alliance with Eritrea, various agreements with Djibouti, and the further strengthening of relations with Sudan.

By the early 2010s, as Iran increased its influence in Iraq and Syria, Saudi Arabia and the UAE were forced to re-examine their foreign and security policies. Their disquiet over Iranian hegemonic ambitions was further heightened in July 2015 with the nuclear agreement between Iran and the West. Saudi and UAE leaders decided to increase military and political coordination and developed a strategy to counter what they perceived as Iranian “expansionism” in the wider region.

The change in their foreign and security policies, however, is not exclusively tied to their competition with Iran; it is also related to the wider political developments brought about by the fake Arab Spring.

Concerned about the possible spillover effects of the uprisings that swept the Middle East in 2011, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE began to gradually exhibit a newfound assertiveness in international affairs, adopting at times a more active stance in their foreign involvements, and even becoming more willing to use their militaries in support of their national interests. Both countries, for example, have sent their armies to Bahrain and Libya and later to Iraq and Syria to fight against ISIS. In place of their prior “quiet diplomacy” there was increasingly a show of assertiveness and muscle flexing in response to security concerns.

The Obama administration’s fatigue with Middle Eastern affairs (Libya, Syria, the Iraq war and of course Afghanistan) and its pronounced pivot toward Asia also fueled this desire to bolster their own security “independence,” without sacrificing the strong strategic partnership with the United States. Times were changing and, having previously relied on the British until they militarily disengaged from the region, the Gulf countries had no excuse to not plan ahead. They were keenly aware of the need to avoid a repeat of history.

Saudi Arabia’s defense spending, for instance, reached a record $82 billion in 2015, and in February and March 2016 the country hosted its largest-ever joint military exercise, North Thunder, with the involvement of troops from 20 countries. In parallel, the United Arab Emirates became the world’s third-largest importer of arms. So pronounced was the shift in security concerns and the strengthening of the country’s military capabilities that James Mattis, the American defense secretary, even went so far as to characterize the UAE as a “little Sparta.”[2] While this is a highly exaggerated comparison, the UAE is looking to not only bolster its military capabilities, but also forge a greater unity and common national identity among its different Emirates through the recent institution of obligatory military service for all Emirati males.

Piracy and Islamic terrorism were among the major threats that led to the upgrade of the African Horn’s importance in the Saudi and Emirati foreign-policy agendas. Seeing threats from al-Qaeda offshoots across the Sahel to the al-Shabab movement in Somalia that had developed close ties with the Yemen-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and other Gulf states recognized that across East Africa’s countries with significant Muslim populations a host of violent and extremist Islamic groups were ranged against both their interests and the security of their nations.

The war in Yemen, moreover, led to an escalation of Gulf-Iran tensions and was a major factor in persuading the Saudis and the UAE of the need to strengthen their regional presence. Both countries were apprehensive about the growth of the Shiite Houthi insurgency in Yemen and the perceived associated Iranian encroachment on the Arabian Peninsula, evaluating them as major threats. Furthermore, the perception that the United States was reluctant to contain Iran made Gulf policy makers more apprehensive. In fact, the Obama administration’s desire to quickly normalize relations with Iran was a source of both tension and contention with the Emirates and Saudi Arabia, which argued, albeit discreetly, that the United States was moving too swiftly without having obtained the guarantees necessary to assuage their traditional allies’ security concerns. When, in March 2015, Saudi Arabia and the UAE decided to militarily intervene in the Yemeni war, it became clear that they would need additional ground forces, ports and air bases. Moreover, it was imperative to secure the support of countries across the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden with whom Iran had developed close relations since the 1990s.

The Horn of Africa has a 4,000 km coastline that runs from Sudan in the north to Kenya in the south and lies astride vital Indian Ocean trade routes. At the Bab al-Mandab straits, where the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean meet, Yemen is just 30 km from Eritrea and Djibouti; and the port of Aden is closer to Mogadishu and Hargeisa than Riyadh. Gulf States estimated that Iran could threaten shipping through the Bab al-Mandab, as it has long sought to do with the Strait of Hormuz. This meant that Yemen’s location was strategic both because it represented the soft underbelly of Saudi Arabia and because of the importance of the straits for both Gulf and world trade.[3]

In this coastline, “where cash-strapped regimes often teeter on the brink of financial survival,”[4] the Gulf states have found willing partners.

In return for financial aid, Sudan, Eritrea, and Djibouti proved willing to support the Saudi-led Operation Decisive Storm against the Houthis. Sudan deployed 4,000 to 10,000 men in Yemen — mainly to secure Aden and its vital port — as Emirati Special Forces fought Houthi rebels in the rest of the country.[5]

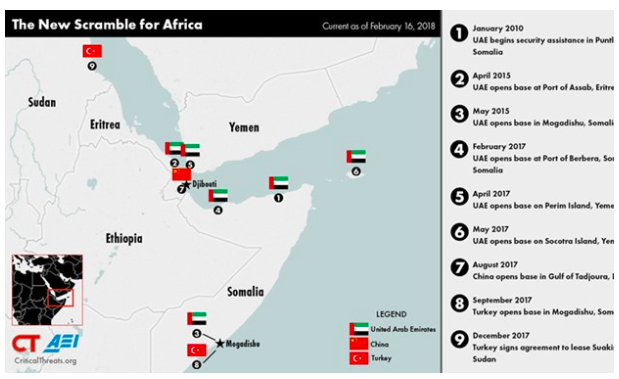

The deployment was rewarded with significant monetary support: in August 2015; Sudan’s central bank announced that it had received a $1 billion deposit from Saudi Arabia. Eritrea leased the port of Assab and the strategically located Hanish Islands to the UAE in return for financial compensation and oil. In December 2016, the UAE signed a renewable 25-year contract for the establishment of an air and naval base in Berbera on the coast of Somaliland(NW Somalia). In June 2015, the UAE foreign minister visited Somalia, and a few days later a shipment of armored vehicles arrived in Mogadishu.[6]

In return, Somalia’s government has allowed its airspace, land and territorial waters to be used by the coalition. By 2016, it was revealed that Djibouti was negotiating the leasing of a military base to Saudi Arabia “to further enable the encirclement of Yemen.”[7] As an analyst argues, “The internationalization of the Yemeni war is proving a major windfall for the Horn of Africa, providing a source of ready cash and diplomatic support for governments in the region.”[8]

Another member of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Qatar, while also engaging in the Horn, took a somewhat different approach. Its troubled relations with Saudi Arabia have resulted in its “minimal participation in every security framework under Saudi influence.”[16] Instead, it opted for a low-profile, rather neutral, policy based on mediation in East African conflicts, often using financial inducements and investments to facilitate the settlement of conflicts.

Qatar’s 2003 constitution had established mediation as a cornerstone of its foreign policy.[9] The emir and the prime/foreign minister, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim Al-Thani, had been involved in the Darfur peace process after violence escalated in 2008. Qatar’s mediation efforts led to a ceasefire agreement signed in February 2010[10] between the Khartoum government and the largest opposition group, the Justice and Equality Movement.

Qatar has also mediated a truce in the Eritrea-Djibouti border dispute and deployed a small contingent of peacekeepers along the border in 2010. However, when Eritrea broke its diplomatic ties with Qatar in 2017, following the sanctions imposed on Qatar by the other Gulf states, Doha decided to withdraw its peacekeepers from the border.[11] In general, Qatari mediating efforts have not proven particularly successful as its “reliance on business ties to lubricate political relationships has [given it] only limited diplomatic influence.” Like Qatar, Oman was careful not to upset its relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran, and remained neutral throughout the conflict in Yemen, offering to mediate on several occasions.[12]

Saudis and Emirates played the role of un-declared agents of Western Empire in Somalia fueling the civil war through tribal communalist competitions and funding for inter-clan militias and warlords the entire 90’s and up 2014.

The Scramble for Somalia’s Geostrategic position in Search for Military Bases and Ports

Khaleeji states of Suadi ,UAE and Qatar plus Turkey have heightened their geostrategic scramble for The Horn of African countries and specially Somalia seeking Economic, diplomatic and Military relations such as Military Bases and commercial Ports since 2014. Thus, competing with each other and the Chinese Belt and Road Infrastructure Initiative (BRI) or/ and Maritime Silk Road (MSR).

For political, economic and ideological reasons, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar and Turkey are locked in a push-pull to set the rules for a Middle Eastern region long in turmoil. Two overlapping rivalries drive and define this engagement: a split within the Gulf pitting Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt against Qatar and Turkey; and competition between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

In strengthening their relationships in the Horn, Gulf states and Turkey hope to secure both short- and long-term interests.

In both those struggles, the main rivals see Africa as a new arena for competition and building alliances, particularly as the Horn is poised for strong economic growth over the next generation. With their significant financial resources, the Gulf countries and Turkey see a chance to adjust the future economic and political landscape of the Red Sea basin in their favour. They are all expanding their physical and political presence to forge new partnerships and ring-fence their enemies – most often one another.

In strengthening their relationships in the Horn, Gulf states and Turkey hope to secure both short- and long-term interests. In the short term for example, the Yemen war made it imperative for Saudi Arabia and the UAE to obtain a Red Sea military base. The internecine Gulf crisis that burst into the open in 2017 accelerated efforts by both sides of the rift to seek new allies. In the long term, each country is jockeying for a prime position in the Red Sea corridor’s economy and politics. Economically, they seek to enter the Horn of Africa’s underserved ports, energy and consumer markets as gateways to rapid economic expansion across the continent. All four describe China as the emerging dominant force in the Horn, and hence one with which they will need to ally, as U.S. and European influence recedes. The UAE, Qatar and Turkey, in particular, view China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI), with projects planned across East Africa, as a chance to bolster their relationships with Beijing.

The tools in this new power scramble range from transactional to coercive. Gulf countries and Turkey can offer aid and investment in amounts that few others can, or in market conditions that many Western firms consider too risky.

Their terms for dispensing aid are often more attractive for local political leaders than those of Western donors. Instead of democratic or market reforms, Gulf states expect preferential access to new investment opportunities and ask aid recipients to take their side in either of the two rivalries in which they are involved. In exchange for military assistance, Gulf states may ask their local allies to push back or suppress domestic political forces aligned with their external enemies.

Conclusions

The Horn of Africa region has been the scene of continuing struggles of foreign actors throughout history.

The centuries-long Ottoman influence in this region has left its place to the colonial activities of the Western countries.

The region had witnessed the competition for the influence of the Soviet block with the West during the Cold War era.

In recent years, a number of new actors such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and China have started to seek influence in the region. While China and Russia have developed significant economic activities in the region, Turkey has been utilizing its historical ties as well as developing its humanitarian aid programme in Somalia and other countries in the region.

The region has been lying in the shores of Gulf of Aden, Bab al-Mandab, and the Red Sea, a route that is one of the most important passages for world maritime trade. Bab al-Mandab is particularly important for Asian trade giants such as China and Japan that exports significant amount of goods to Europe through this route. In addition, a great deal of the oil and natural gas exports from the Gulf countries to the European market are shipped through the Gulf of Aden, Bab al-Mandab, and the Red Sea route. Therefore, for many countries, the stability of this region is of great importance.

The region is important also since it is considered to be one of the most important entry points to the African market by the leading countries of Asia and the Middle East. This is indicative of China’s investment in Ethiopia and Russia’s efforts to develop closer economic and political relations with regional countries such as Eritrea and Djibouti. Another country that closely follows the region, in this sense, is the United Arab Emirates. Two UAE economic giants, Abu Dhabi and Dubai, export significant amount of goods to Africa. The two Emirates also serve as a hub for other countries and international companies that seek business with the continent.

This makes the Emirati ports as a crucial transfer point for big companies that export their goods to Africa. While global firms, including Nestle, use Dubai as the hub of African operations, thousands of containers leaving China and India for Africa arrive at the port of Dubai to be transferred to Africa.

This trend has derived from the increasing volume of trade, particularly from Dubai to Africa, over the years. Between 2008 and 2013, non-oil trade from Dubai to Africa increased by 700 percent.[14]

The tools in this new power scramble range from transactional to coercive. Gulf countries and Turkey can offer aid and investment in amounts that few others can, or in market conditions that many Western firms consider too risky. Their terms for dispensing aid are often more attractive for local political leaders than those of Western donors. Instead of democratic or market reforms, Gulf states expect preferential access to new investment opportunities and ask aid recipients to take their side in either of the two rivalries in which they are involved. In exchange for military assistance, Gulf states may ask their local allies to push back or suppress domestic political forces aligned with their external enemies.

This competition for influence raises risks of new conflict. The Gulf states and Turkey each say they are seeking “stability” in the Horn, but their definitions differ dramatically and put their interests directly at odds. Saudi Arabia and the UAE view civil unrest as something to control lest the region become a playground for Sunni Islam-inspired political movements or Iran. They privilege short-term stability imposed by strong security states. Although they urge allies to open their markets to investment, they would rather bandage economic grievances and postpone hard reforms that would threaten the status quo. Qatar and Turkey, meanwhile, are more inclined to see popular uprisings as a way to empower groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood that they believe will promote their interests in the long run. Yet the Brotherhood and its local spinoffs have overreached in some cases since the 2011 uprisings by imposing their ideological agendas and thus creating as many new grievances as addressing existing ones.

With their competing views, these two camps consider relationships in the Horn to be a zero-sum game, pressing states to take sides and supporting domestic opposition groups or local leaders if national capitals do not oblige. They can do this because relations between the Gulf and the Horn are deeply asymmetrical and favour the former.

While competition and rivalry may serve [Gulf’s] immediate political and commercial goals, it is just as likely to harm the long-term stability of a fragile region.[16]

The Somali Federal Government and political leadership feels that the Emirates are intervening aggressively in Somali internal affairs; stalking communal/ clan warfare; encouraging balkanization of Somalia; funding and encouraging Al-shabab and fostering regional insecurities since 9/11

Moreover, they are acting willingly as Agents of US/NATO as well as of USAFRICOM’s “Global war on terror “(GWOT). The latter is directed towards towards Somalia contributing to weakening Horn Of Africa countries from an economic and military standpoint.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Prof. Dr. Bischara Ali Egal is Executive Director, Chief Researcher of The Horn of Africa Center for Strategic and international Studies (Horncsis.org)

Notes

1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_history_of_Somalia (accessed december 29,2019)

2) https://mepc.org/journal/gulf-states-and-horn-africa-new-hinterland (accessed 29, 2019)

3) Ibid

4) Ibid

5) Ibid

6) Ibid

7) Ibid

8) Ibid

9) Ibid

10) Ibid

11) Ibid

12) Ibid

13) https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/206-intra-gulf-competition-africas-horn-lessening-impact (accessed December 30, 2019)

14) http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2018/05/lost-love-horn-africa-uae-180528092015371.html(accessed December 29, 2019)

15) Afshin Molavi, the Emerging Dubai Gateway to Africa, John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies – Foreign Policy Institute, 9 October 2014, https://www.fpi.sais-jhu.edu/single-post/2014/10/09/The-Emerging-Dubai-Gateway-to-Africa;(accessed 29thDecember, 2019)

16) Ibid