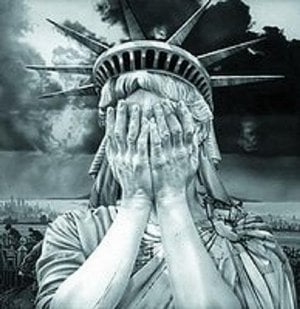

Keeping Torture “Fashionable”: The US Presidential Elections

It never goes away: a state’s imperative to torture. What seems to matter is the degree of honesty officials have in terms of whether its deployment is secretive, incidental or central to the policy of obtaining information. Under the Obama administration, a degree of moral abhorrence for its use has prevailed. Republicans have not been so sure.

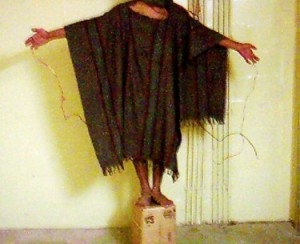

US political debate has never quite banished the bogey of torture, which tends to find form in what are termed techniques of interrogation. This is despite the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) that deems illegal any act that causes “severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental” and is intended to obtain a confession, gather information, punish a subject, pressure the subject or someone else into behaving in certain ways, or “for any reason based on discrimination of any kind.”

As Matthew H. Kramer posits in a University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research Paper (No. 2, 2015), “punitive torture” may no longer be practiced in any liberal democracy but “the matter of interrogational torture is still a live point of contention.”[1] Such temptations have been hard to resist, dragging and stretching legal arguments to the point of breaking.

As Matthew H. Kramer posits in a University of Cambridge Faculty of Law Research Paper (No. 2, 2015), “punitive torture” may no longer be practiced in any liberal democracy but “the matter of interrogational torture is still a live point of contention.”[1] Such temptations have been hard to resist, dragging and stretching legal arguments to the point of breaking.

Indeed, there is much to suggest that the legalism that often arises in such debates tends to find form in odious proposals that legitimise, rather than outlaw, torture. Something as blatantly contradictory as Alan Dershowitz’s torture warrants are shining examples of that tendency. This is despite Dershowitz’s own admission that torture is a “horrible practice that we all want to see ended”.

His point, rather, is that of a psychologist preaching about the inherent brutality of his subject, eternally aggressive. Cruelty is ineradicable in state conduct – why, therefore, resist the calling of nature?

The US electoral atmosphere is filled with grim promise of revived regimes of torture. This threatens to effectively overturn the Executive Order made by President Barack Obama in 2009 banning the use of waterboarding, sleep deprivation and sexual humiliation.[2] The National Defense Authorization Act for 2016 also imposes restrictions on abusive interrogations.

The GOP presidential frontrunners seemed reluctant from the start to rule out the use of such techniques as waterboarding. Executive orders are, after all, rescindable matters, revocable at a moment’s crisis. Chris Christie argued while still in the race that such methods could hardly make the grade as torturous. “We should do whatever we need to do to get actionable intelligence that’s within the Constitution.” Ben Carson, speaking to ABC’s This Week in November, argued that, “There’s no such thing as political correctness when you’re fighting an enemy who wants to destroy you.”[3]

Marco Rubio insisted on opposing an amendment in 2015 enshrining a torture ban into US law, claiming that it was important that future presidents have “important tools for protecting the American people.”

Trump, as ever, promised with bravado that he would “bring it back”. After the Brussels attacks, the front runner drummed up the rhetoric of waterboarding as necessary and useful. “I’m not looking for breaking news on your show but frankly, the waterboarding, if it was up to me, and if we changed the laws and – or have the laws, waterboarding would be fine.”

What of Ted Cruz, the only other GOP rival Trump really has to be concerned about? For one, Cruz describes the experiences of his father, Rafael Bienvenido Cruz, who had fought for Fidel Castro in his teenage years against the Battista regime. “When you grow up in the home of an immigrant who’s seen prison and torture, who’s seen freedom stripped away, you grow up with an acute appreciation for how precious and fragile our liberty is.”[4]

Initially, commentators noted his stance against torture as “legally” defined. But in so doing, he was invariably going to be excluding certain acts such as “vigorous interrogation” or “enhanced interrogation”.

Waterboarding was exactly one such technique. “Well under the definition of torture,” he claimed in February, “no it’s not. Under the law, torture is excruciating pain that is equivalent to losing organs and systems.” This odd, not to say daft qualification, provides Cruz with the excuse to then operate with impunity as a potential commander-in-chief.

Were he to squeeze into the White House, he would still insist on the “inherent constitutional authority to keep this country safe”. In facing an “imminent terrorist attack,” a Cruz presidency would insist on “whatever enhanced interrogation methods we could to keep this country safe.” These become distinctions without relevance.

Such statements go to show that under a Cruz or Trump presidency, the doors of torture will remain open with various degrees of enthusiasm (the former less than the latter), with flashing green lights to interrogators to make their quarry talk. And who can blame them? Even by Obama’s weak admission, “we tortured some folks” – but that was hardly a reason to prosecute officials.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes: