Jordan Valley – Stolen Land: Israel Destroys Schools, Prohibits Construction, Water or Electricity Connections

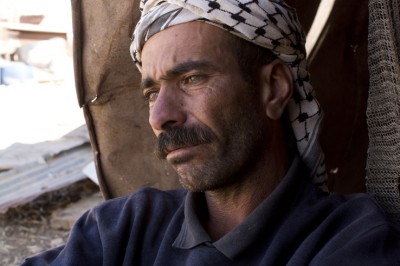

Photo: Burhan Basharat, father of eight, sits in the remains of his destroyed home in West Bank village of Khirbet al-Makhoul, Jordan Valley, October 9, 2013. Photos by: Keren Manor, Ryan Rodrick Beiler, Oren Ziv / Activestills.org

The Jordan Valley in the Palestinian West Bank is under active annexation to Israel – in breach of the 4th Geneva Convention. Victoria Brittain went there to explore what this means for the people of the Valley, and the implications for John Kerry’s ‘peace negotiations’.

Traumatised barefoot children, silent exhausted mothers, desperate fathers, now living in new shelters, spoke of their ever-present fear of army and settler violence.

Northeast of the Palestinian city of Nablus the road towards the northern Jordan Valley and the international border with Jordan runs for miles alongside almost empty ranges of rocky brown hills designated on UN maps as ‘Israeli Nature Reserve’.

Much of the road has concrete posts every hundred yards inscribed “DANGER Firing Zone”, and the UN maps also shade it as an Israeli closed military area.

The ever-present fear of violence

But every few miles there are tents or simple structures of Palestinian farms with sheep and cows in makeshift pens visible, set back below the hills.

In recent weeks and months defenceless families in this remote place have had their homes and farms repeatedly destroyed by military bulldozers in dawn raids.

Traumatised barefoot children, silent exhausted mothers, desperate fathers, now living in new shelters, spoke of their ever-present fear of army and settler violence.

This area is part of a flashpoint in the current Israeli-Palestinian negotiations being pushed by US Secretary of State John Kerry.

Israel wants to keep the whole Jordan Valley for at least the next 40 years. The US has suggested stationing international troops there. And in the meantime Israeli politicians are openly talking up annexation of the whole valley up to the border with Jordan.

Oslo hopes betrayed

Much of the Jordan Valley was designated in Oslo 2 as Area C – the 60% of the West Bank where Israel has complete control, and has used it systematically to force Palestinians out in the 20 years since the false hope of the first Oslo Accords in 1993.

In Area C construction is prohibited, no water or electricity connection allowed, schools and water pumps put up by aid agencies are destroyed, health care is almost absent. Israeli settlements, outposts and military bases proliferate.

Five thousand Palestinians live in 38 communities in parts of Area C like these designated as ‘firing zones’ for military training. An occasional crump of artillery could be heard in the distance, and twice we saw soldiers in the hills or on the road.

Burhan Basharat stands inside a makeshift animal shelter that was build after his house and farm were demolished in West Bank village of Khirbet al-Makhoul, Jordan Valley, October 9, 2013. All photos and captions from A week in the demolished West Bank village of Khirbet Al-Makhoul, 972mag.com, October 12,2013.

Kirbet al Makhoul

Burhan Bisharat’s village of Kirbet al Makhoul was destroyed four times in two weeks in late September last year. With no warning or demolition notices the bulldozers drove up the dirt road before dawn and brought down tin homes, hay sheds, animal pens, water troughs and a playground with swings belonging to the twelve families.

Today Burhan, his wife, and youngest daughter are visibly traumatised and he spoke softly of how the psychological pressure, especially of the fourth destruction, was very, very difficult for him.

He saw relief tents brought by the ICRC put up and immediately brought down by a bulldozer in front of the aid agency staff.

The three now live in another almost empty replacement home half the size of what they had before and which Burhan built himself in two days, bringing an aluminium roof from Nablus.

But every day is lived under the shadow of another onslaught that they know can hit their lives any time.

A Palestinian man whose house was destroyed organizes his tent in the West Bank village of Khirbet al-Makhoul, Jordan Valley, October 7, 2013.

Hard choices – and Tony Blair

This is a father who took the very difficult decision to send his seven older girls to live a few miles away in a small town where they go to school. His oldest daughter is 17 and in the twelfth grade and is in charge of the little household of children.

“I want my children to have a better life through education … it is best to keep them away, though it is very tough for them to be alone, and (with a gesture to his silent wife) for their mother.”

Burhan is only 38, but the harshness of his life has made him look and seem a generation older.

Sipping hot tea sitting by the door of his home, sheltering from the cold rain, Burhan spoke at length and scathingly of the foreigners who have failed to protect his family and community – Ban Ki-Moon, Catherine Ashton, and above all, Tony Blair.

“How could a man who brought destruction on such a massive scale to Iraq dare to come then to Palestine claiming he could bring peace? From the day after his appointment destruction here worsened.”

A life’s mission – to stay put

Burhan will never move off this land and the livelihood he makes tending his 250 sheep, and dozen chickens that survived the demolition – unlike his pigeons which all died. It is, he says, his life’s mission to hold onto it, and his children will follow him.

“If I moved, the Israelis would take my land … a Jew could come from Ethiopia and replace me here … how can this be normal?” He speaks quietly, anger contained, but sadness for his family overwhelming the conversation.

Today’s relentless pressures on Palestinians’ land here is nothing new. Makhoul had 70 families before it was destroyed by Israel in 1967, like another dozen nearby villages in the Jordan Valley north of Jericho. Over the years after 1967 families gradually returned to their land and rebuilt their farming lifestyle in all these villages.

Today farmers like Burhan talk of the new Israeli pressure in the valley, the mushrooming settlements, increased village demolitions, scaring the shepherds away from land near military bases and setting fire to grazing land.

Today farmers like him have to buy feed for their sheep and cows and watch their livelihood become even more precarious.

Palestinians, aided by Israeli solidarity activists, clear the remains of demolished shelters in the destroyed West Bank village of Khirbet al-Makhoul, Jordan Valley, October 11, 2013.

Fragmentation and dispossession

The loss of Palestinian land in this group of villages in the north-eastern West Bank is a microcosm of the total picture of fragmentation of community, and dispossession.

The Wall, the settlements, the settler-only roads, the checkpoints and the redrawing of the West Bank map have left Palestinian towns and villages, such as Qalqilya and Azzun Atma to the west of Makhoul, completely isolated.

Like so many communities they are cut off from what remains of their land, or it is accessible only through locked gates, which only a few family members (often the elderly) have permits to pass through for a few hours a day.

The scale of this dispossession is impossible to convey.

A struggle less visible

There is another rather less visible on-going power struggle than the one for the land. It is for the future of Palestinian youth. This too is more than half a century old.

The road north-east from Nablus towards Burhan’s village passes what local people call a black spot of British Mandate history here – a rock above the El Far’a valley known as ‘execution rock’ where men were forced to jump to their deaths.

El Far’a camp was a British police station in 1932. Today a football field is visible from the road and a community organisation is housed in the main building. But behind it is the old British police horses’ stable wing, later a training camp for Israeli soldiers from 1967 to 1982.

Burhan cleans his ground in the destroyed West Bank village of Khirbet al-Makhoul, Jordan Valley, October 9, 2013.

Sharon’s legacy

In 1982 El Far’a was made into a special prison for youths aged 15 to 22 by the late Ariel Sharon, then Minister of Defence. El Far’a was directly under his ministry, not the normal prison service.

Ahead of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Palestinian youths were rounded up from all over the West Bank and held in tiny crowded cells, interrogated in the old stables, humiliated by being held naked and addressed only by a number, in Hebrew.

“It was the middle of nowhere, they were alone, no family, no lawyer, no way to know the time or the days”, said one local man who has collected the memories of those held there 50 years ago.

I have once before seen such unforgettable images of these whitewashed narrow cells, with every inch covered in prisoners’ scratched writings and with one small window too high for a prisoner to reach.

That was in a 2004 visit to Israel’s infamous Khiam prison in remote occupied southern Lebanon. Palestinians and Lebanese were held here from 1985 until the Israeli army withdrew in 2000 and the prisoners were liberated.

Obliterate the evidence

In 2006 Khiam, which had become a place of historical education for a new generation, was bombed flat by Israel. El Far’a too had its smallest punishment cells removed by the Israelis when they left this village after Oslo.

A chance mention of the El Far’a visit a few days later, miles away in the south of the West Bank, gave me a story from a man who was in the first group of youths taken there, 30 years ago.

He described the drive north with a jeep full of youths arrested from Hebron and other towns, and taking two days as the soldiers did not know the way to remote El Far’a.

Eventually one of the boys said he knew it and offered to guide them, saying, left, right, right, straight, left, left, until they were completely lost through the night, and the boy got a good beating from the soldiers.

Once they finally arrived they found the man in charge of the new prison was from central Europe, new to Israel, and new to prison experience. The boys, many of whom were not new to Israeli prisons, told him the rules were that he should buy them newspapers every day and fruit and vegetables.

It was a good few days before the local commander visited the prison, fired the novice governor, and got down to the business of beatings, interrogations and isolation.

Imprisoned: 40% of Palestine’s male population

Listening to this sophisticated man discussing those days I remembered that 800,000 Palestinians have been in Israeli jails since 1967 – 40% of the male population.

These days, in the company of lawyers or social workers who work with families where children have been arrested and imprisoned, the men’s own prison experiences are very often the key to the empathy which allows them to reach these traumatised children.)

In more than ten years of visits to the West Bank and Gaza I have sat with the mothers of Palestinian child prisoners listening to their stories of trauma which have changed children into adults.

These are tales of violent night arrests, handcuffs, shackles, beatings, isolation, signing statements in Hebrew when the child does not understand the language, appearances in Israeli military courts, pleading guilty to stone throwing in the hopes of being released, being held in prison inside Israel where family visits (arranged by the ICRC) are rare.

A generation intimidated

Today 173 Palestinian children are held in Israeli jails. As 30 years ago in El Far’a, Israeli soldiers are trying to intimidate a whole young generation by random arrests.

However, visiting Aida camp in Bethlehem and seeing children in Al Rowwad centre’s drama workshops, journalism training, photography and dance groups, or Burhan’s girls from the Jordan Valley, sacrificing home life for education, or the children of the Nasser family on a hilltop farm called Tent of Nations, completely surrounded by settlements south of Bethlehem, who have learned ballet from YouTube, tried break-dancing and horse riding, or schoolgirls from East Jerusalem who have made a CD of rap songs, or students from Gaza whose writings are published as a book in the US, is to see Palestinian children who determinedly seize normal childhoods despite the extraordinary context of violence they live in.

Silwan

Another current focus of violence is the Palestinian town of Silwan on the edge of East Jerusalem, just outside the Old City.

Silwan is perched on a steep hillside, a warren of tiny alleys and steep staircases. An Israeli settlement organisation Elad, has been given control of much of the area and they plan to make it into a tourist destination and a public garden.

The beginnings of the garden can already be seen and some Palestinian houses have already been taken over by armed settlers, and others have been bulldozed. Currently 88 Palestinian homes here have demolition orders on them and a thousand people live with the stress of imminently losing their homes.

In Rula Badran’s home, high over the valley, she served tea before telling an everyday story of Silwan’s children. Rula’s husband sat silently alongside and their son Mohammed sat next to him.

A schoolboy’s tale

Mohammed is a high achieving schoolboy, 14 years old with carefully styled hair, who took up the story after his mother. Rula saw him playing with his friends on the street after school as she was on her way home from shopping. He offered to carry her bags home, but she refused, saying she was fine.

Within minutes a friend of his arrived at the house, saying that Mohammed had been arrested. “I thought he was joking, I’d been with him two minutes before.”

She went out and found that Mohammed was indeed sitting with policemen. The police asked for her ID and she sent another child home to bring it. “I was not going to leave my son for a second.”

A crowd of neighbourhood children gathered to surround her and protect her and Mohammed, tension mounted and the police began hitting children to clear them away.

Mohammed was pushed into a jeep and Rula forced her way in too, shouting, “before you take away my son from me you can kill me first.” She was not allowed to speak to him in the jeep. Inside the police station her son hung onto her in complete terror, saying,“don’t go, don’t go.”

After his father came she left Mohammed and he stayed there for four hours with his father. The police said they were waiting for the special investigator for children to arrive. Finally they were sent home and told to come again the following morning.

The following day the child was interrogated by a Hebrew-speaking investigator and an interpreter, and asked if he had thrown stones, or which of his friends had thrown stones.

“There were no cars around, no stone throwing, I was just going to fetch my laptop when this one car arrived and a policeman called me over”, he explained.

He was finger printed and signed a paper in Hebrew, which he didn’t understand. “I signed because I was afraid.” Ever since there has been a police jeep parked outside his school.“For nothing, just to keep us frightened.”

Honest broker?

Any week of travelling to listen to Palestinian families from north to south and east to west of the West Bank will reveal hundreds of these dignified families and communities under violent attack from settlers, military, and the bureaucrats designing the new Israeli security state that John Kerry’s team will underwrite with the US’s $3 billion plus aid per year to Israel.

There will be no viable Palestinian state and no real end to Occupation to come out of these fraudulent negotiations.

Victoria Brittain is a journalist and writer. She has spent much of her working life in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, writing for The Guardian and various French magazines. She has been a consultant to the UN on The Impact of Conflict on Women, also the subject of a research paper for the London School of Economics.

Her most recent work is a verbatim play, Waiting, with the words of the wives of Guantanamo and other prisoners. She was co-author of Moazzam Begg’s book, Enemy Combatant. She is on the Council of the Institute of Race Relations, the Board of Widows Rights International, and is a Patron of Palestine Solidarity.

This article was first published by Open Democracy as The fourth destruction: stolen land and childhood under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 licence.