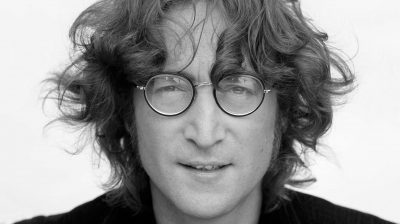

John Lennon, Celebrated in Havana

The anniversary of John Lennon’s death (December 8) was marked in Cuba. Criticism followed on social media: Cuba repressed Beatles music forcing kids under the covers. Abel Prieto and Guille Vilar, youth in Cuba at the time, say it’s not true. [i] But that’s not the point.

More useful, Prieto argues, is what happened to Lennon’s message in the US. One result, celebrated this past August, was the “existential explosion” of Woodstock. Prieto wonders why such a powerful experience did not end in effective resistance to hatred.

Cuba had no “existential explosion”, although Eusebio Leal uses such language. Leal has been city historian for Havana since 1967. When appointed, he had grade five education. He’s directed the restoration of Old Havana, world heritage site since 1982, celebrated at Havana’s 500thbirthday.

Asked how he did it, Leal says the revolution “exploded” into his impoverished life. He and his single mom were Christians and he still practises. He is philosopher, although never trained, formally. He’s received awards and recognition from around the world.

The Cuban Revolution didn’t exactly “explode”. Leal was awarded his PhD in History for work on Carlos Manuel de Cespedes.[ii] edes freed his slaves in 1868, initiating a war. The 1959 revolution started there, even before. Cespedes was a philosopher, a fascinating one, as Leal explains.

Many such revolutionaries were philosophers. They discovered ideas explaining actions that couldn’t be explained within existing theory. If you act, and can’t explain, at least to yourself, you feel crazy. You can’t sustain direction.

At a Party Congress in 1997, Fidel Castro said direction was everything. He didn’t say getting it right was everything, although it matters. Charles Darwin didn’t get it all right, but he defined direction. He raised questions that led to explanation of what previously had not been explained, and that needed to be explained, to understand what needs to be understood to move forward: in a direction.

“Existential explosion” needed explanation, to define direction. Martha Ackman’s wonderful new book on Emily Dickinson shows a way.[iii] We meet an engaged, active Dickinson whose home was the “wild terrain of the mind”. She wanted her poems to be true, so that a poem does indeed convey the sense of the bird. That her poems were called true was praise she valued most.

Early on, as a student, “Emily wanted to stare [the unknown} down and walk straight into the abyss”: truth. She never shied away from “looking anguish in the eye“. It was her “dominion over misery“. She saw in the dark, that is, she saw things in the dark: life.

Today the only “dominion over misery” is “light at the end of the tunnel”. In an early poem, Dickinson writes, “We grow accustomed to the Dark – Either the darkness alters – Or something in the sight adjusts itself to Midnight.” And so, we see life.

It links her to Cespedes. He saw in the dark. Dickinson thought there could be truth, not just about birds, but about the sense of a bird. Thus, she applies a criterion connected to the world. Some feelings are true as regards what is lived and can be lived. Some are not so true.

It’s mind/body connection. Feelings, sometimes, are from the world, indicative of how it is, or might be. But many want “light at the end of the tunnel” and only that.

I was reminded of this by Javier Cercas’ Lord of all the Dead.[iv] Cercas writes about his great uncle who died for Franco. His death was “seared into my mother’s imagination in childhood as what the Greeks called kalos thanatos: a beautiful death.” Like Achilles, he lives on.

By the end of Cercas’ compassionate story, the great uncle is no longer a symbol of shame but rather a “self-respecting muchacho“ lost in someone else’s war. But Cercas tells the story for the sake of telling the story. That’s what he says. The story must be told because it’s better than to “leave it rotting”.

It can’t, for instance, be a story explaining what needs to be explained , such as the “silent wake of hatred, resentment and violence”, left behind by the war. Cercas can’t make this claim. “Silent wake” is a metaphor. It can’t be fact. Cercas sets these in opposition, repeating it, four times: Legend is unreliable, dependent on people, “volatile.” Facts are something different: “safe” and “brutal”.

Mercifully Dickinson didn’t have this view. Otherwise, her poems couldn’t be true. Cercas is in the sordid grasp of an old story, separating the personal from the objective, as if the latter is achievable only if freed of the former. “Beautiful death” is the same story: human beings apart from nature.

It makes freedom from decrepitude worth speculation. And speculate Cercas does. He ends with immortality. Nobody dies, we learn; we’re just transformed, physically, living in an “eternal present”.

It’s better to see in the dark, not with silly views about “hope” but by finding stories that explain direction. To say science and art are connected is not to say they are the same thing. Unless you imagine how the world might be, even if it can’t be that way, you don’t ask why it is the way it really is.

John Lennon sang about this. Europeans pulled apart art and science, in a false view of truth and knowledge, linked to a false view of human beings in nature.

Cuba tells a different story. So does Dickinson.

Cuba didn’t repress Lennon’s message. It explains it, in art and philosophy. Eusebio Leal is part. The beauty of Old Havana is the beauty of the ideas that explain its stunning restoration. Ideas explaining what needs to be known, for a direction that can be lived, with dignity, have claim to truth.

They’re not stories for the sake of stories: European liberalism’s hidden recipe for despair.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Susan Babbitt is author of Humanism and Embodiment (Bloomsbury 2014). She is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Notes

[i] http://www.cubadebate.cu/opinion/2019/09/27/la-cebra-que-le-hemos-hecho-a-lennon/#.Xf4JnUdKiM8

[ii] Carlos Manuel de Céspedes : el diario perdido (Havana: Ediciones Boloña, 1998).

[iii] These Fevered DaysW.W. Norton & Company, 2020. Review forthcoming https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/

[iv] Translated by Anne McLean, Alfred A Knopf, 2020.Review forthcoming https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/