Jeb Bush Proves He Has No Clue About US Economics

Jeb Bush, one of the leading Republican candidates for the presidency, is in the news again—and not in a good way. During a meeting with the editorial board of the New Hampshire Union Leader, he reportedlysaid the following:

“My aspiration for the country — and I believe we can achieve it — is 4 percent growth as far as the eye can see…Which means we have to be a lot more productive, workforce participation has to rise from its all-time modern lows. It means that people need to work longer hours and, through their productivity, gain more income for their families. That’s the only way we’re going to get out of this rut that we’re in.”

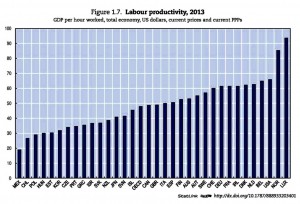

There are so many delusional statements in this paragraph that one is hard-pressed to know how to make sense of it. First, the problem is not the productivity of the American workforce. The BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics) says that “Labor productivity measures output per hour of labor.”According to the chart below, the United States has the third highest productive work force among similarly advanced countries. Only Norway and Luxembourg have a more productive workforce than the U.S. among OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries.

If the American workforce is third in productivity among advanced economies, more productivity will not to solve the ills—wage stagnation being the biggest one—that beset the American workforce.

If the American workforce is third in productivity among advanced economies, more productivity will not to solve the ills—wage stagnation being the biggest one—that beset the American workforce.

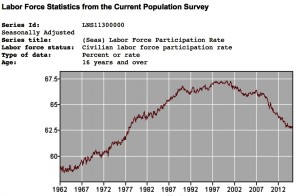

Second, the decline in workforce participation (labor force participation rate) is not the problem that Jeb Bush and the Republicans want to make it out to be. As the chart below shows, labor force participation peaked in April 2000 at 67.3% and has been declining ever since. In June of 2015, it stood at 62.6%. If the decline was due to poor economic policies on the part of President Obama, then Jeb Bush must explain why it declined under the policies of his brother, President George W. Bush as well.

The majority of economists who analyzed the the problem of declining labor force participation found the cause to be structural and not in the control of a certain person or a certain institution.FactCheck.org suggested three reasons for the decline:

“1) The aging of baby boomers. A lower percentage of older Americans choose to work than those who are middle-aged. And so as baby boomers approach retirement age, it lowers the labor force participation rate.

“1) The aging of baby boomers. A lower percentage of older Americans choose to work than those who are middle-aged. And so as baby boomers approach retirement age, it lowers the labor force participation rate.

2) A decline in working women. The labor force participation rate for men has been declining since the 1950s. But for a couple decades, a rapid rise in working women more than offset that dip. Women’s labor force participation exploded from nearly 34 percent in 1950 to its peak of 60 percent in 1999. But since then, women’s participation rate has been ‘displaying a pattern of slow decline.’

3) More young people are going to college. As BLS noted, ‘Because students are less likely to participate in the labor force, increases in school attendance at the secondary and college levels and, especially, increases in school attendance during the summer, significantly reduce the labor force participation rate of youths.”

All three reasons for the decline in labor force participation are outside the control of Jeb Bush or any other Republican or Democratic candidate running for office. These are structural problems that cannot be solved by adopting one policy over another.

If the U.S. workforce is productive and the declining labor force participation rate is not reversible through government action, then what is the cause for the income stagnation that Jeb Bush correctly identifies?

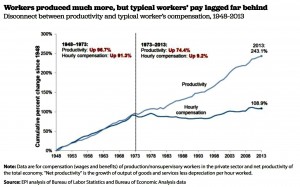

The chart below shows the relationship between compensation (wages and benefits) and productivity in the U.S. since 1948. Between 1948 and 1973, hourly compensation tracked improvement in worker productivity. The productivity trace line increased in an almost equal amount to the compensation and wage trace line. Basically, as U.S. workers became more productive, they received a compensation that is somewhat in line with the improvement in productivity. In other words, corporations were willing to share more of their profits that came by way of productivity with their workers.

In contrast, from 1973 to 2013, worker productivity increased by 74.4%%, but compensation increased by only 9.2%. Put differently, compensation and productivity diverged from each other. This has had a very damaging effect on the wage growth of 90% of Americans. Due to changes in the taxation system and the trading system (corporate trade agreements), American corporations were no longer sharing the fruits of productivity with the working class and were either moving profits overseas or passing on the profits to CEOs with massive compensation packages. The CEO-to-worker compensation ratio increased from 20:1 in the early 1970s to 303.4:1 in 2014.

In contrast, from 1973 to 2013, worker productivity increased by 74.4%%, but compensation increased by only 9.2%. Put differently, compensation and productivity diverged from each other. This has had a very damaging effect on the wage growth of 90% of Americans. Due to changes in the taxation system and the trading system (corporate trade agreements), American corporations were no longer sharing the fruits of productivity with the working class and were either moving profits overseas or passing on the profits to CEOs with massive compensation packages. The CEO-to-worker compensation ratio increased from 20:1 in the early 1970s to 303.4:1 in 2014.

The American working class is one of the most productive in the world. Increasing its productivity will not help improve its stagnant income as long as the profits from it accrue overwhelmingly to corporations. Many would argue that corporations should be incentivized—through the tax system and corporate trade agreements—to share rising rates of productivity with the workers, as they were between 1947 and 1979. These were the years of shared prosperity that made the United States the envy of the world.