Japan and the Hanaoka Massacre of Chinese Forced Laborers, Summer 1945

Introduction by Franziska Seraphim

The Hanaoka Massacre

When U.S. occupation forces liberated Allied POW camps in the Akita area in northern Japan in the early fall 1945, they came across piles of unburied dead bodies, mass graves, and a labor camp of emaciated Chinese men living in appalling conditions.

This was Chūsan Dormitory near the Hanaoka copper mine and river diversion project run by Kajima Corporation, one of Japan’s biggest construction and public works companies. Kajima-gumi, as it was then known, was headquartered in Tokyo with branches throughout Japan and Manchuria. The company had built Japan’s first hydroelectric dam in the 1920s and would remain at the forefront of innovative engineering projects in Japan and Asia throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century.1

In the closing years of the war, Kajima participated in a nation-wide system of forced labor from northern China and Korea ostensibly to offset labor shortages in Japan and to maximize industrial and mining production, including at the Hanaoka mine. Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and most other industrial combines used forced labor as well.

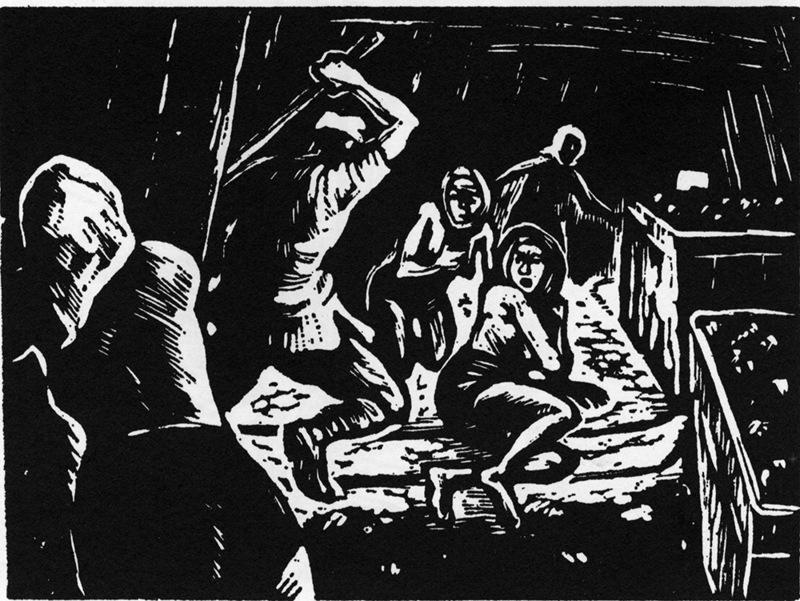

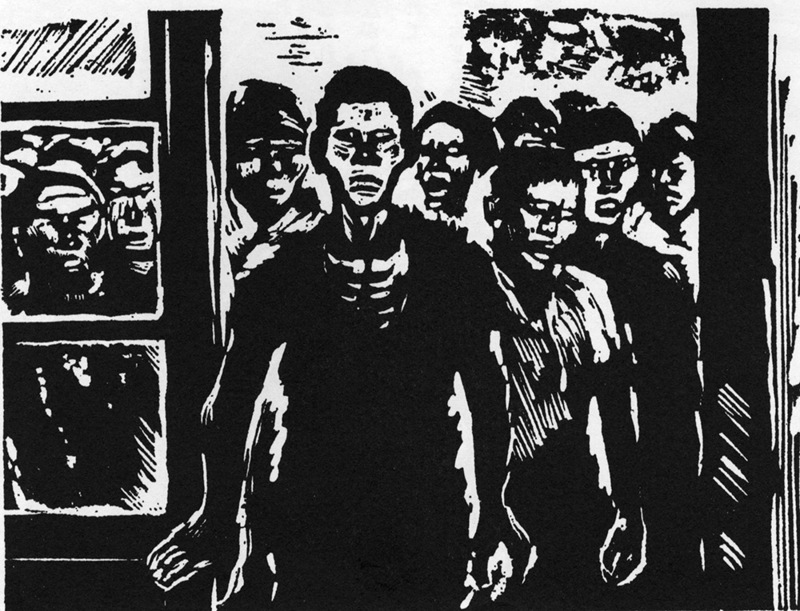

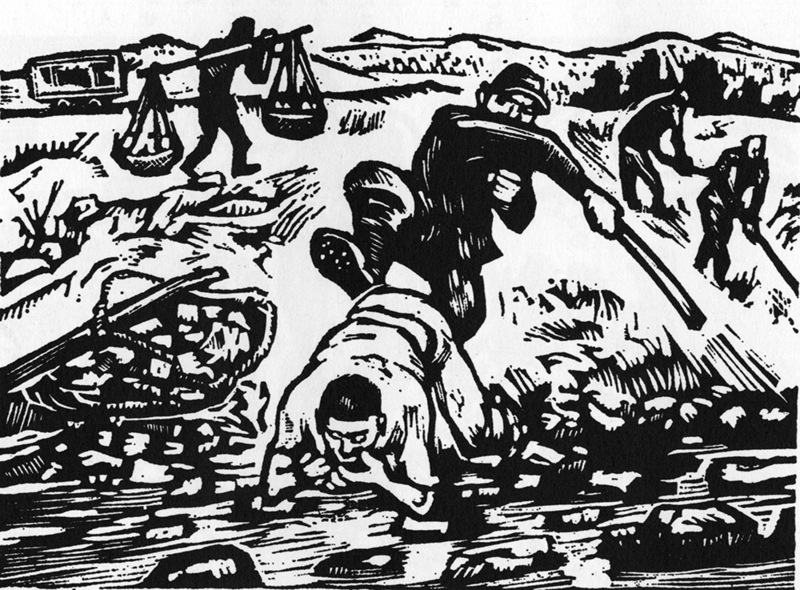

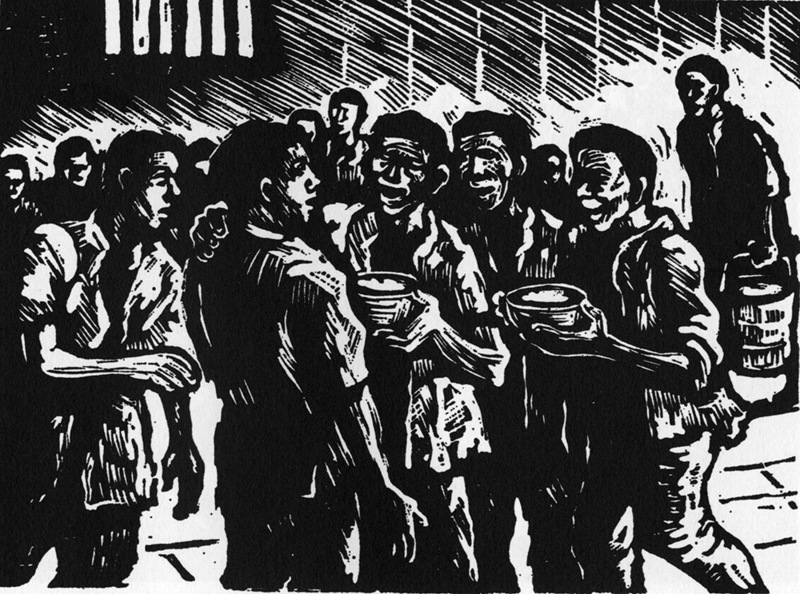

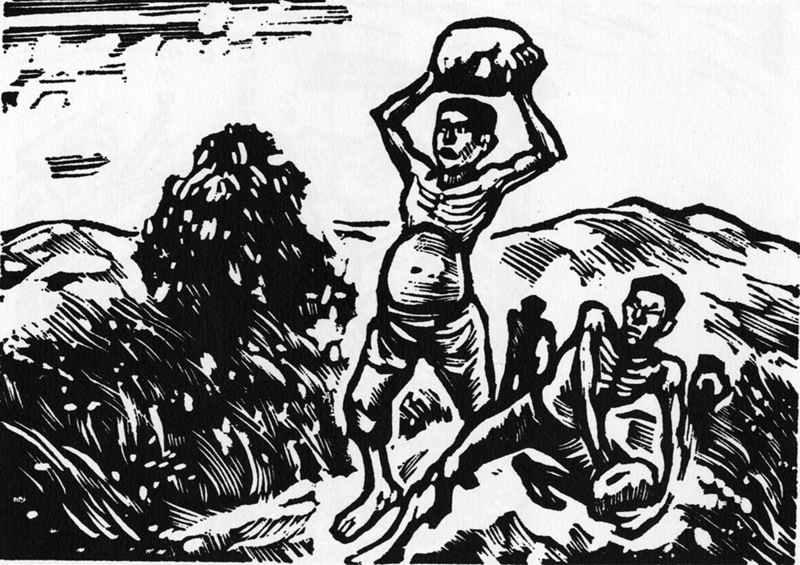

Nine hundred eighty-six Chinese civilians and prisoners of war from five north-Chinese provinces were brought to Hanaoka in three waves between August 1944 and June 1945 to join Korean conscripts, Allied POWs, and Japanese laborers moving ore cars into and out of the mine, repairing roads, cementing, excavating river beds, and tilling the rocky land. Working conditions worsened for everyone as food supplies dwindled towards the end of the war. But the Chinese workers were singled out for ever-increasing levels of physical and mental abuse, especially severe beatings. Food rations and living conditions at Chūsan Dormitory deteriorated to sub-subsistence levels in the last year of war. including starvation, unsanitary living conditions, systematic beatings and plain murder.

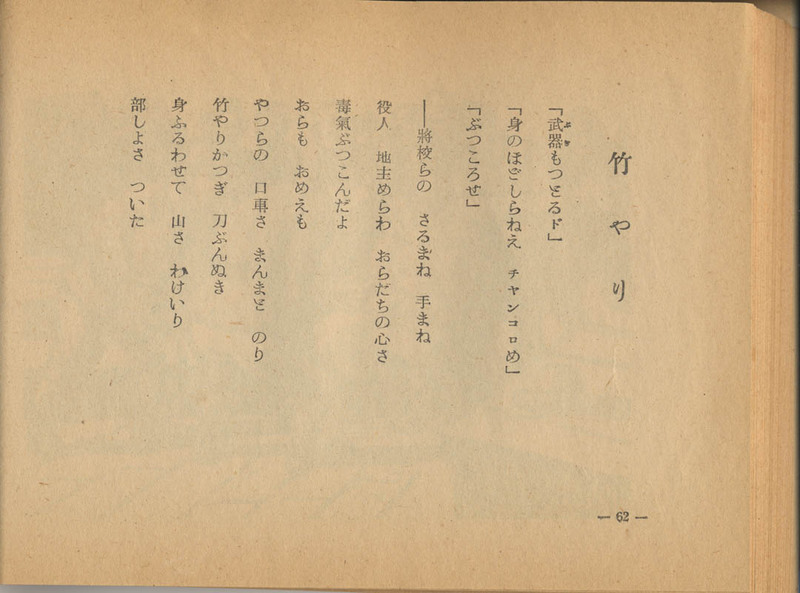

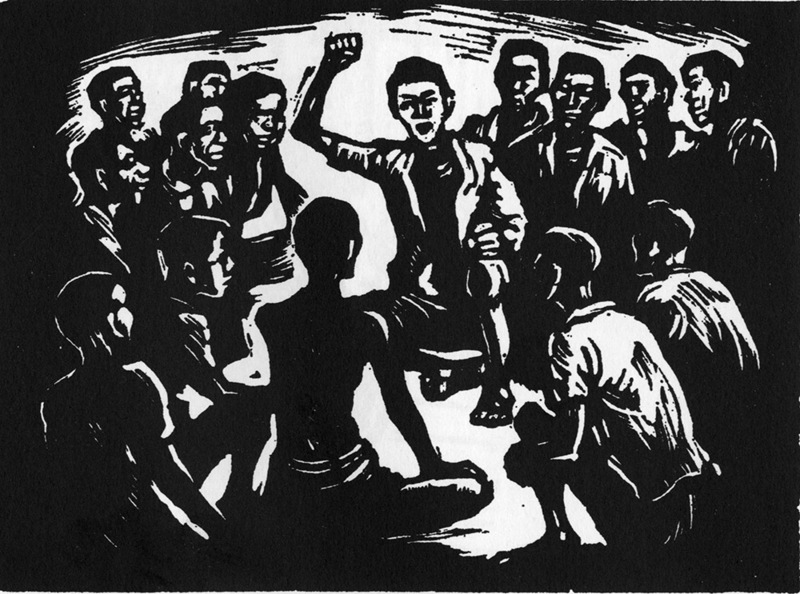

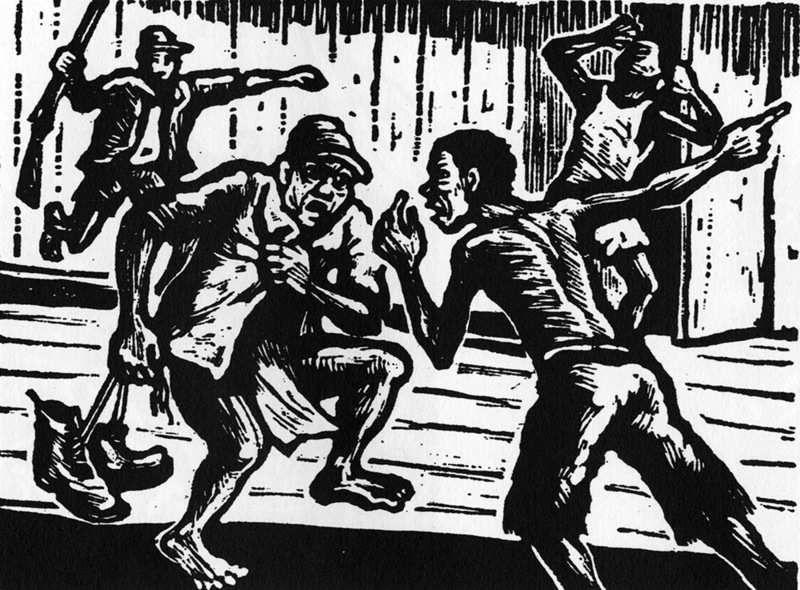

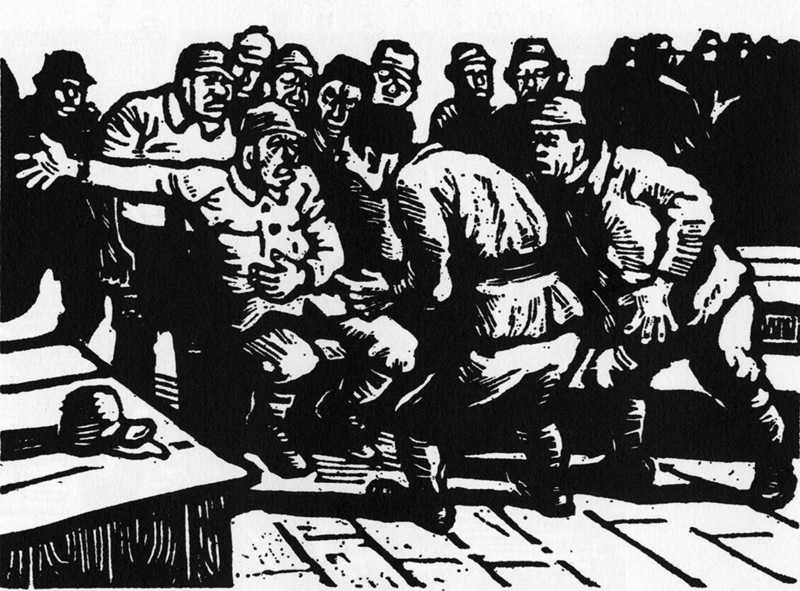

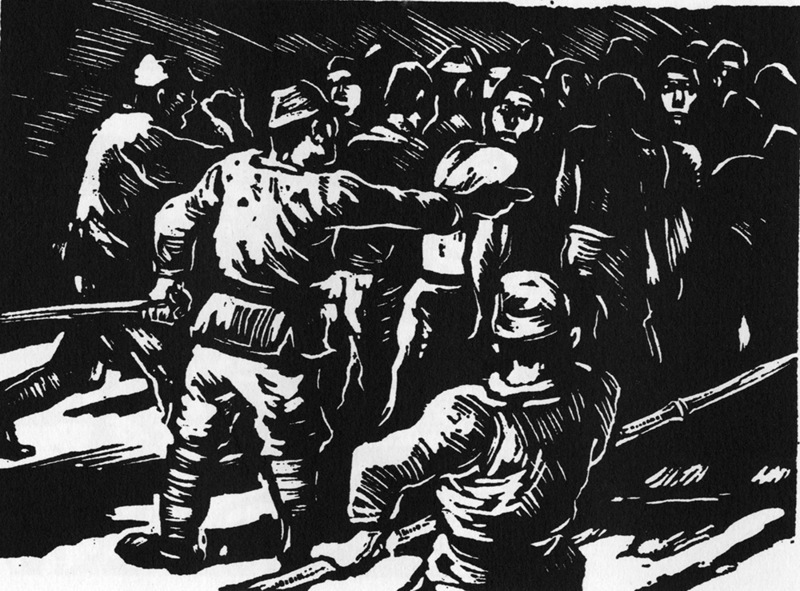

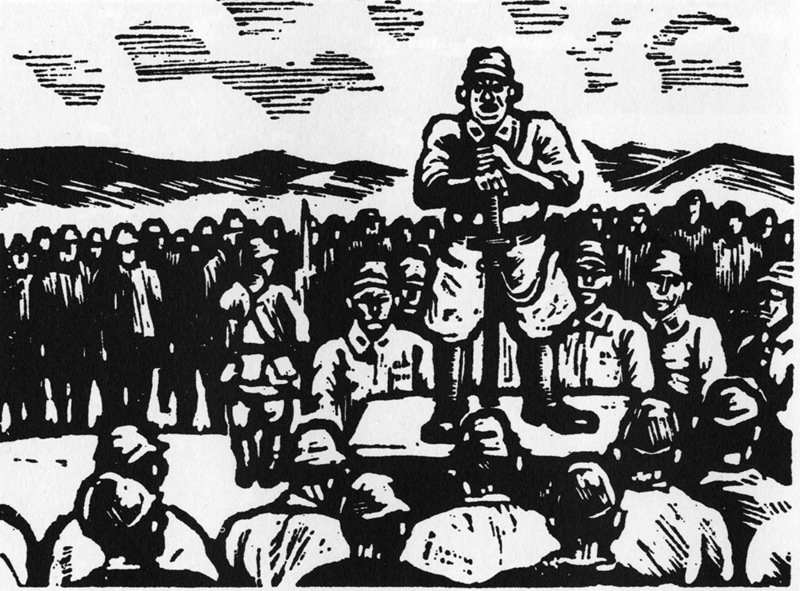

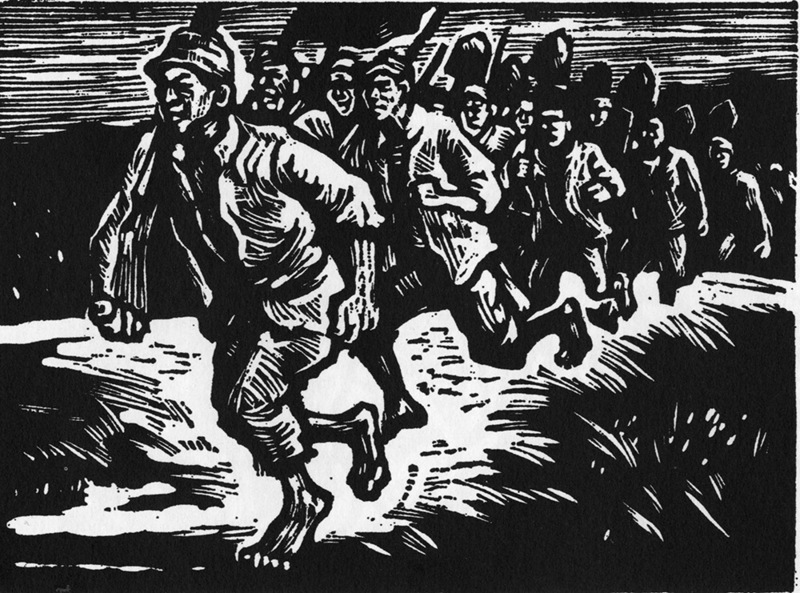

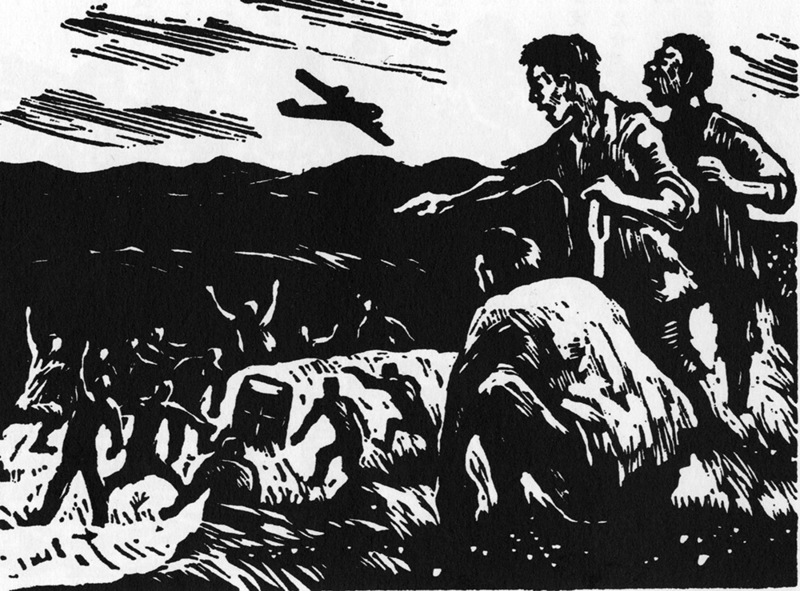

“Dogmeat Stew” On June 30, 1945, six weeks before the war ended, the men at Chūsan Dormitory organized an uprising, killing four Japanese overseers and one Chinese spy and fleeing into the woods, from where they tried to defend themselves with rocks. Over the following four days, local and military police recaptured the rioters with the help of locals and tortured them in the Hanaoka town square. Over 200 Chinese died in what has come to be known as the Hanaoka Incident, and the dying continued at a high rate in the months to follow. Between August 1944 and October 1945, 418 Chinese died of malnutrition, illness, physical abuse and plain murder. A first report on the incident by Japanese authorities on 20 July 1945 titled “On the Riot by Chinese Workers of Kajima-gumi” found that the excessive workload, severe food shortages, and lack of compensation lay at the root of the revolt. It also established that “[the Chinese laborers] were treated like animals and beaten whenever they stopped working for a pause…” The report notwithstanding, the inhumane treatment continued even past Japan’s surrender and extended to the dead as well, who were denied proper burial. Kajima-gumi simply ignored an August 1945 SCAP directive stipulating an end to all forced labor, payment of wages, release of prisoners, collection of remains, and repatriation. Later in the fall, the head of a U.S. investigation into forced labor at Hanaoka, William Stimpson, furnished a thirty-page report on the atrocities in preparation of war crimes indictments. This led to the arrest of Kajima’s president and thirteen top officials as well as camp supervisors, guards, and policemen who worked in or around Hanaoka during the last year of the war. Occupation authorities evidently found Kajima’s corporate leaders too central to reconstruction efforts to pursue the company’s criminal responsibility for forced labor and released the officials in 1946 after payment of a fine to the Lawyers’ Association. Criminal investigations instead focused on the day-to-day perpetrators of brutality in the camp. A U.S. military commission of the Eighth Army in Yokohama found six out of the indicted eight camp supervisors, guards, and policemen guilty of war crimes against the Chinese laborers as Hanaoka. On 1 March 1948 the court sentenced two guards and one camp commander to death, the Hanaoka general manager to life, and two policemen to twenty years of hard labor each. Over the following decade all sentences were gradually commuted by the U.S. Clemency and Parole Board in the course of bringing the Allied war crimes trial program to an end. Despite repeated clemency appeals on their behalf, the Hanaoka camp guards ended up in the “hard core” category of war criminals who were the last to be released from Sugamo Prison between 1956 and 1958. The trial unearthed much gruesome detail about the slave labor conditions in Hanaoka and the massacre in particular but was otherwise fraught with contradictory witness testimony, coerced affidavits, and controversy over the very legitimacy of the trial. In the face of Allied war crimes investigations, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs launched its own investigation of all 135 forced labor worksites in March 1946. Besides the Ministry’s investigative reports, each company involved, including Kajima, was ordered to furnish its own site report. Meanwhile, state bureaucrats crafted a five-volume “Investigative Report of the Working Conditions of Chinese laborers” also known as the “Foreign Ministry Report.” Based on exhaustive statistics from different ministries, it provided detailed information on all 38,935 Chinese males brought to Japan as forced laborers, their hometowns, procurement through the North China Labor Association, transport to Japan, working conditions in Japanese mines, docks, and factories, causes of death, etc. This report has a fascinating history in its own right, as it was successfully kept from the Allied war crimes investigation in the 1940s, “vanished” in the late 1950s, and only reappeared in 1993 when NHK (Japan’s national broadcasting service) launched an aggressive investigation for a documentary on wartime forced labor. In documenting the system of forced labor broadly, the Foreign Ministry Report sought to draw attention away from individual businesses involved and instead to demonstrate that the forced labor system as a whole had been a failure for Japan, for it had neither alleviated the acute shortage of labor nor brought companies financial relief. Perhaps the most problematic part of the report was its use of falsified death records supplied by the company site reports, which claimed that many Chinese laborers had died of diseases they had contracted before coming to Japan rather than of abuse and murder on site.2 The Creation of Hanaoka Monogatari None of the official investigation reports of the Hanaoka Incident were allowed to become public knowledge in the early postwar year, and all vanished from the record thereafter. The war crimes trial was subject to Allied censorship at the time and—apart from the announcement of the verdict—could not be discussed in the public media. The only information about the Hanaoka atrocities in the media at that time appeared in articles in the left-wing monthly journal Shakai hyōron in 1946 and the Communist newspaper Akahatain 1947. But local Japanese in the Akita area knew. They remembered. And some of them acted when the political time was ripe. That time came in 1950, when the Occupation was entering its fifth year and its priorities had changed from ensuring Japan’s democratization to building up a strong military alliance with Japan’s conservative leadership. SCAP (the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers) had come to see the People’s Republic of China, as a threat to Japan’s peace and reconstruction and to suspect the Korean minority as well as pro-China activists of communist infiltration. This change of policy, which began in 1947, came to be dubbed the “reverse course” in the Japanese media. For the political Left, the reverse course centered on the so-called Red Purge in 1950, when more than 20,000 teachers, labor and peace activists deemed communists or communist sympathizers lost their jobs, while erstwhile militarists who had been purged under early postwar Occupation directives were being rehabilitated and many soon returned to public office. The critical context both for the Red Purge and a growing peace movement was China’s Communist Revolution, culminating in the formation of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949 and the outbreak of war on the Korean Peninsula the following June. In 1950, then, in response to both international and domestic political developments, Japan’s labor movement, the peace movement, and the Sino-Japanese friendship movement joined forces. Hanaoka Monogatari was a product of a heightened sense of crisis among the left, which saw itself as representing the (peace-loving) Japanese people resisting the (remilitarizing) Japanese state. Three local woodcut artists from the Akita area sat down to create what was for decades virtually the only public source of information on the Hanaoka Incident: a collection of 56 woodcuts, each accompanied by a poem in the Akita dialect, telling the story of the Chinese forced laborers at Hanaoka. A three-month strike at the electric engineering company Hitachi following 5,555 job losses proved decisive for the genesis of this project. The struggle cost Hitachi’s regional art cooperative director Maki Daisuke his job. Barred from work under the American-sanctioned Red Purge, Maki spent his time recording the Hitachi struggle (Hitachi Monogatari), the farmers’ movement (Jōhō Monogatari), and finally the Hanaoka Incident (Hanaoka Monogatari) through lengthy pictorial narratives.3

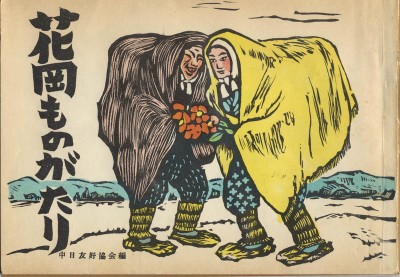

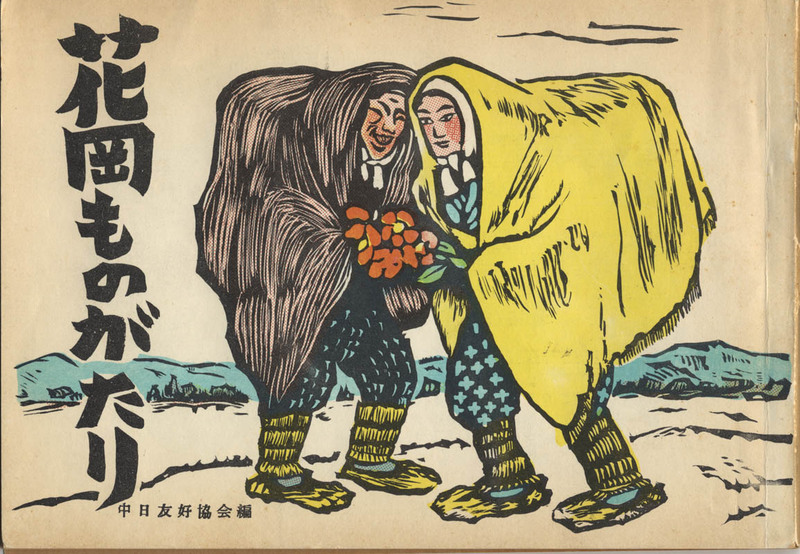

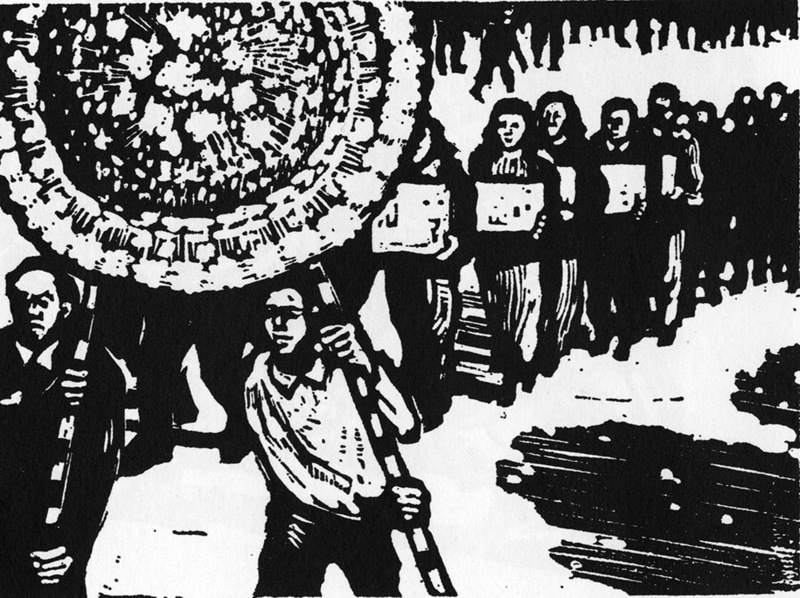

Under the slogan “Never forget Hanaoka,” Maki Daisuke worked with two artist friends, Nii Hiroharu and Takidaira Jirō, and the poet Hara Tarō while finding refuge at the home of the Akita branch representative of the newly founded Japan-China Friendship Association. It was also the Friendship Association that first published Hanaoka Monogatari in book form in May 1951 and promoted its 1956 appearance in China, where it became a bestseller under the title “The Hanaoka Disaster.” The disappearance of the original woodblock panels at around this time put a hold on subsequent editions, although a reprint of an existing copy was published in 1971, some years after a local committee of the Japan-China Friendship Association erected a five-meter-tall stele near the site of the former Chūsan Dormitory.

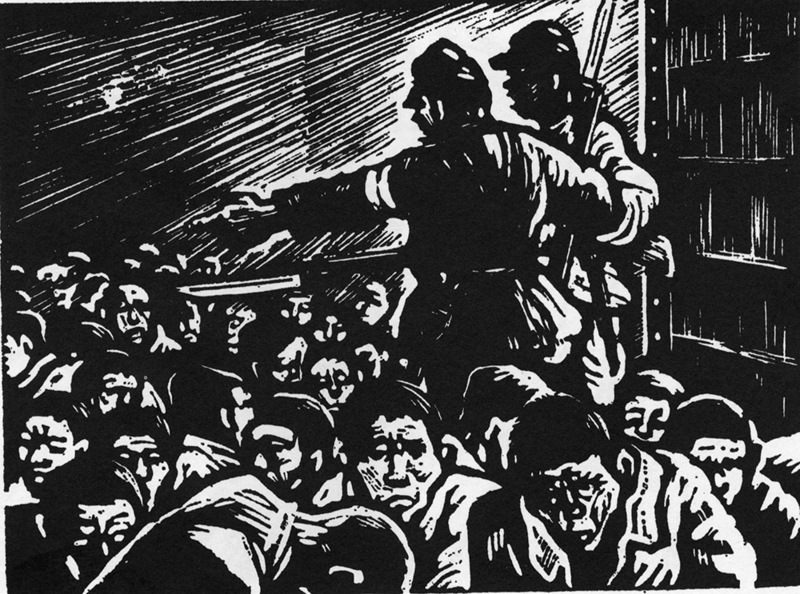

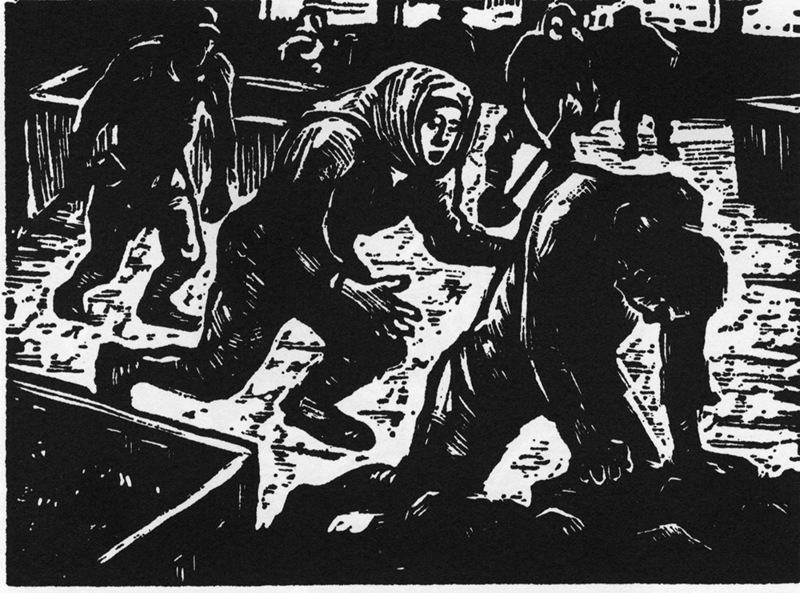

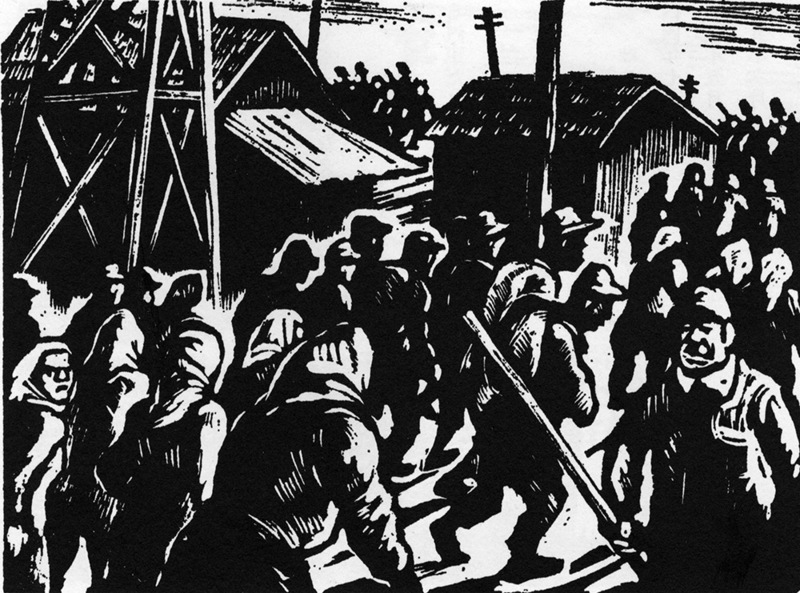

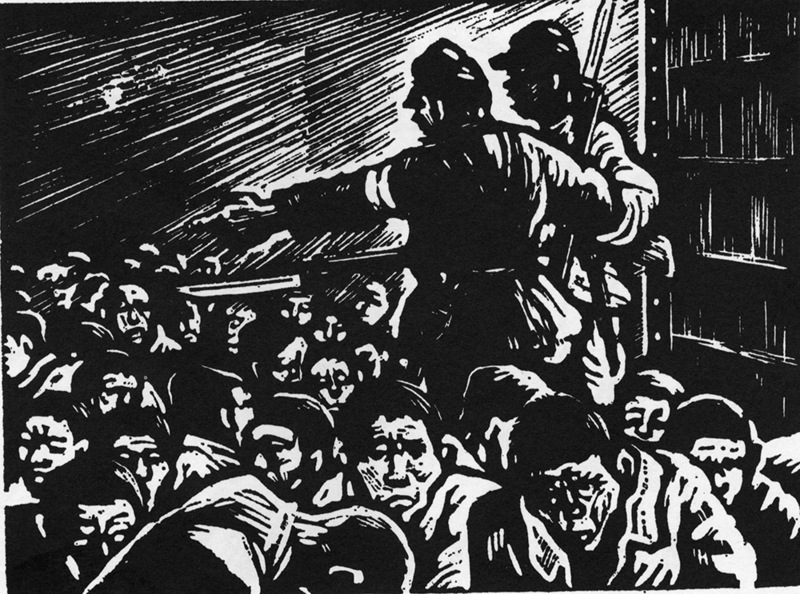

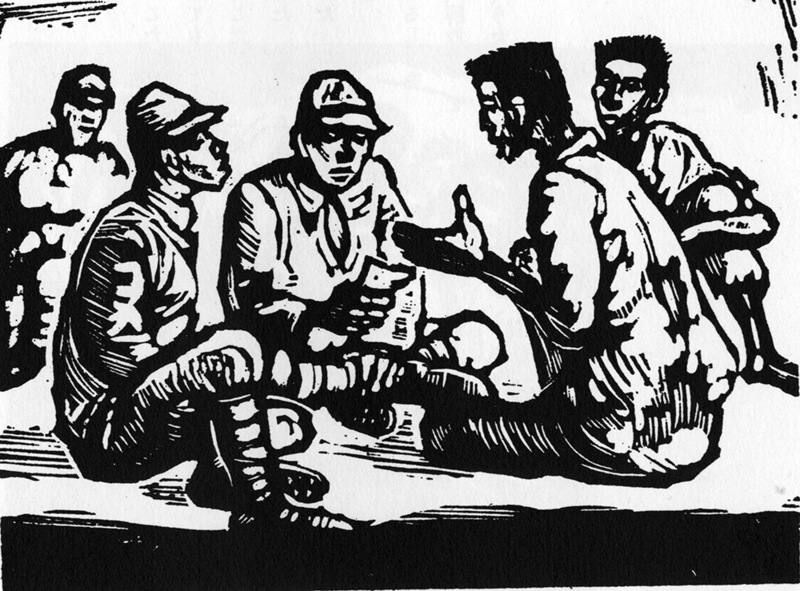

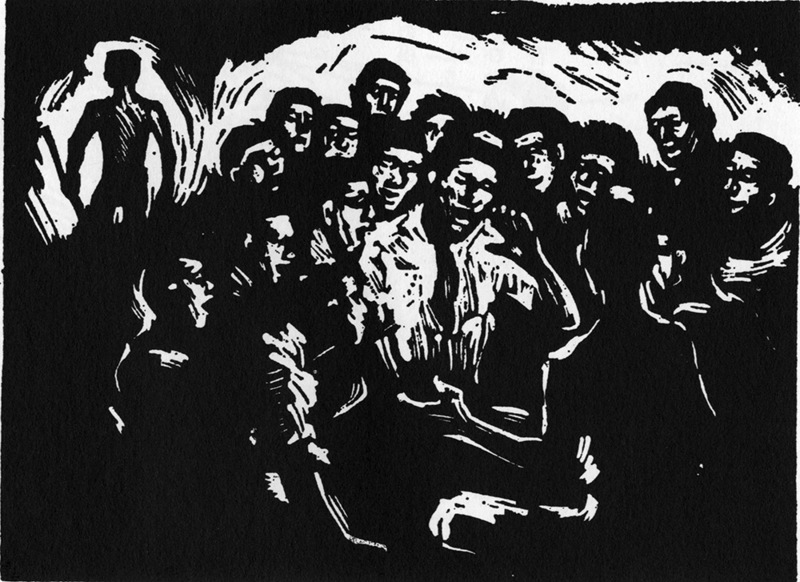

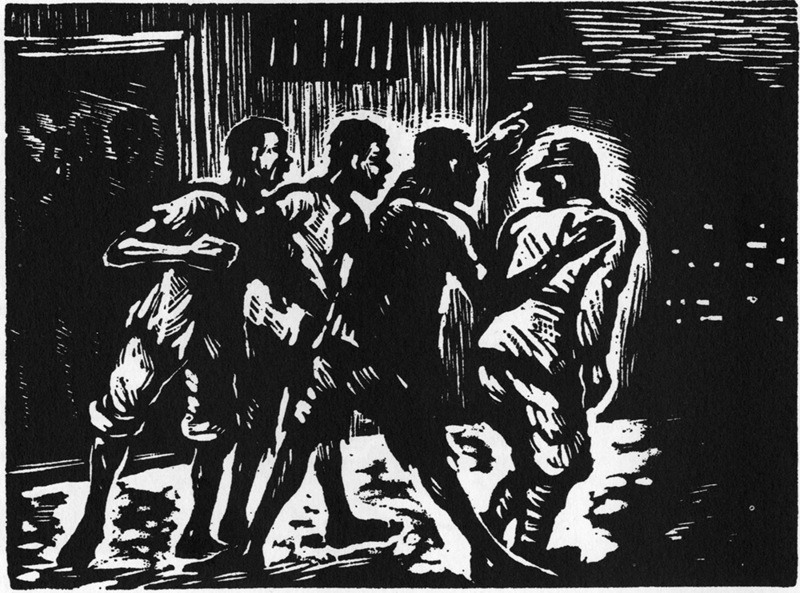

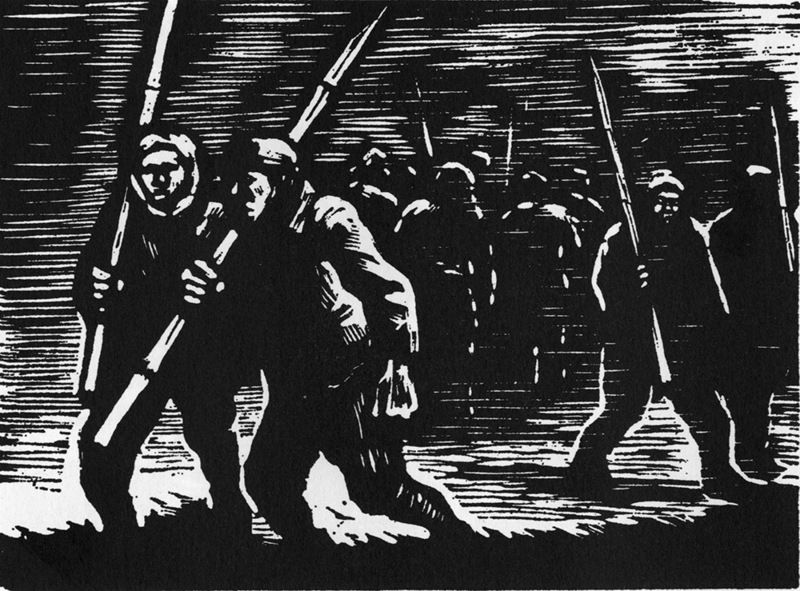

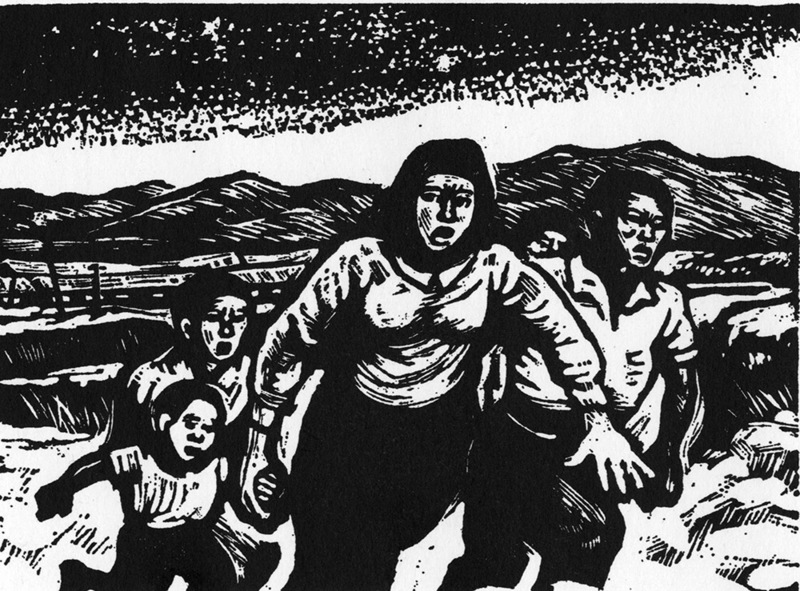

A documentary on the Hanaoka Incident by the Akita NHK TV station based on this book followed in 1975, when public interest in the issue began to emerge. A second edition became possible in 1982, after the original wood panels were located through the efforts of the radio and newspaper reporter Nozoe Kenji, who had been researching both the historical event and the history of Hanaoka monogatari since his days as a logger in the Hanaoka area in the 1950s. Mumeisha Publishing put out the most recent edition in connection with the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war in 1995. Hanaoka Monogatari did more than just document the June 30 massacre. It paid tribute to the suffering and heroism of the Chinese laborers caught in the vicissitudes of capitalism gone rampant under wartime militarism and imperialism. The facts about the Chinese laborers’ procurement and transportation to Japan, their life and work in Hanaoka, the organization of the uprising, the massacre, and finally postwar struggles over issues of responsibility are well corroborated by the U.S. war crimes trial records as well as newly rediscovered Japanese records. The pictorial story’s narrative and interpretive scope, however, differed greatly from both U.S. and Japanese records on Hanaoka. American investigations focused narrowly on a selected handful of perpetrators whose crimes could be conclusively verified by legal means in a trial whose very legitimacy was questioned at every turn. Japanese government reports all but buried specific crimes within a larger bureaucratic system of importing and controlling foreign labor having gone wrong. Maki Daisuke and his colleagues, in contrast, told the story from the perspective of local Japanese workers forced to become accomplices in the crimes against Chinese workers. It mattered greatly to Maki and his colleague that, although the Chinese laborers had suffered alongside poor Japanese farmers and other locals, Korean conscripts, Allied POWs, and even student soldiers, the Chinese were singled out for the most inhumane treatment of all.5 Being literally worked to death, denied adequate clothing, food, and water while subjected to beatings with shovels, cudgels, and swords—all this was depicted with frightening candor. While social class united the workers at Hanaoka in the face of capitalism serving the aims of war, ethnicity separated them by the hierarchical logic of imperialism. Class solidarity, moreover, was betrayed when the military police enlisted local Japanese to recapture the Chinese rioters.Hanaoka Monogatari was meant to restore this solidarity by celebrating the Chinese (and Korean) laborers’ courage, resilience, and belief in liberation. Their resistance served as a bittersweet example, and a call for action among the workers of contemporary Japan to rise up against a state that once again ignored the welfare of working people, allied itself with the new imperialists (America), and denied its responsibility towards China.6 Maki Daisuke was apparently also motivated by a sense of personal allegiance to his home (furusato) and the responsibility that this entailed. Growing up in difficult circumstances, he had spent some of his student years at his uncle’s place in back of the Kyōrakkan theater on the square where the Chinese rioters were tortured for days after the uprising. In creating Hanaoka Monogatari, he paid tribute to the Chinese victims of this incident that marred part of what he called home and, in his view, simultaneously exposed the deadly—and continuing—conjuncture of capitalism, imperialism, and war. It is therefore significant that these local Akita artists chose a medium that had come to visually define the anti-Japanese resistance movement in China among left-wing artists in the 1930s and continued into the 1940s as the Chinese revolutionary woodcut movement. The human characters depicted through rugged bold lines in black and white brimmed with the rage of humiliated, destitute people and their call for liberation. Perhaps the most famous of these woodblock prints was Li Hua’s “China, Roar!” (1935).

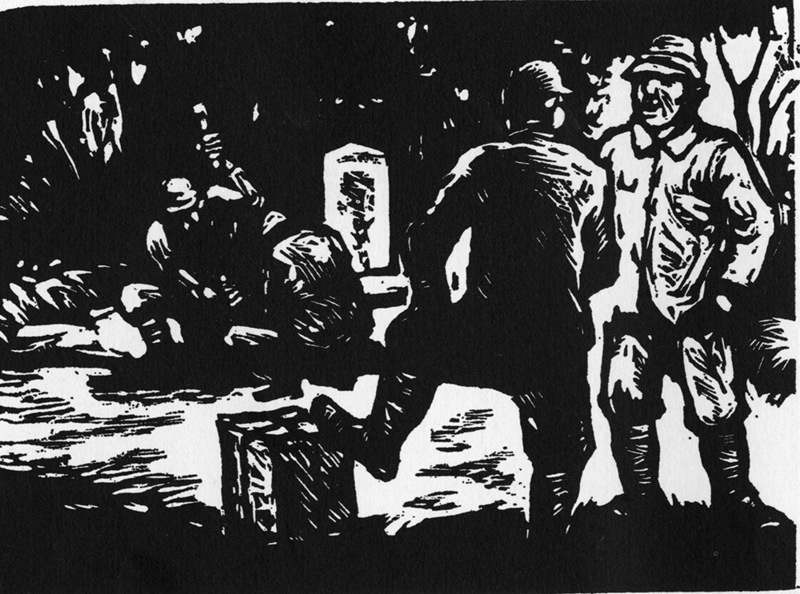

This modernist political art form had emerged in Shanghai around the writer Lu Xun in the 1930s, but its roots were quintessentially international. A wave of translated European and also Japanese modernist and socialist art theory had deeply influenced Chinese artists in the 1920s, and Lu Xun himself promoted the engagement with these art forms by exhibiting his collection of the German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s work and by using foreign modernist art to illustrate his novels. He was also principally responsible for the promotion of the narrative picture series as an accepted art form in China at that time. Precisely how Maki Daisuke and his collaborators came to adopt this art style is impossible to reconstruct, but it most likely depended on personal contacts both during and after the war. We know that cross-national relations among left-wing artists and intellectuals critical of Japanese imperialism flourished during the war, centered on Uchiyama Kanzō’s bookstore in Shanghai also known as the Japanese-Chinese Culture Salon. The floor above the bookstore served Lu Xun as a refuge in the years before his death in 1936; moreover, Lu Xun invited Uchiyama’s brother to teach Japanese woodcut styles to Chinese artists there. Uchiyama Kanzō went on to become the Japan-China Friendship Association’s first president from 1950 to 1953, when many Japanese with deep cultural connections to China joined the movement.7 Hanaoka Monogatari’s most harrowing prints were undoubtedly those depicting the extreme brutality of the Japanese overseers, which started well before the Chinese men arrived in Hanaoka. In the poems accompanying the three slides entitled “Why were there Chinese at Hanaoka?” the victims themselves told their Japanese co-workers at Hanaoka the story of their abduction in China and the suffocation, beatings, and drowning to which Japanese men subjected them on their way to Japan.

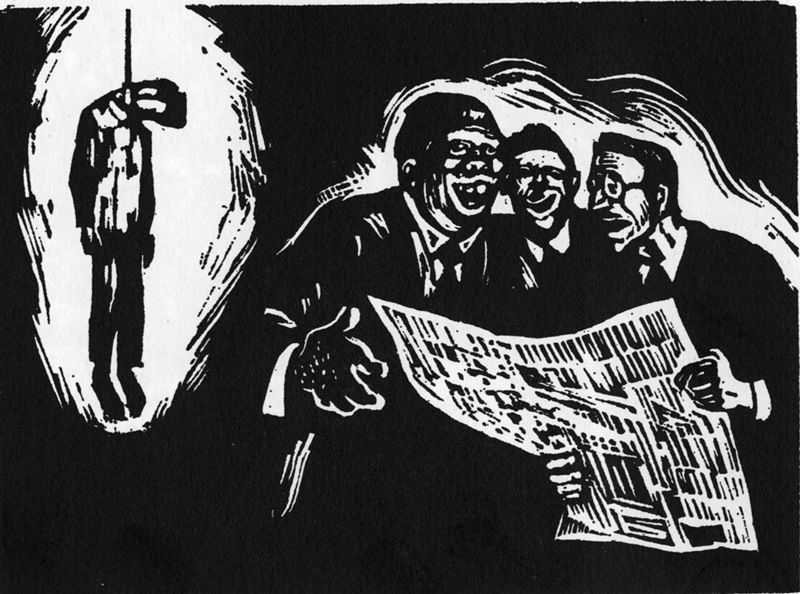

Thereafter, the narrative voice changed to the Japanese workers witnessing the trampling and beating of their Chinese co-workers at the hands of the Hanaoka camp guards. In all these prints, the well-nourished, almost oversized Japanese with their swords, spears, and brutal faces exuded a dark, ruthless presence of total control on the one hand, and out-of-control behavior on the other. Just as in the Chinese war-resistance woodcuts, the few bold white lines against the overwhelming darkness of the print left no space for moral ambiguity. Postwar Japanese avant garde artists such as Yamakawa Kikuchi and Tomiyama Taeko further explored the links between the war and postwar exploitation of workers, in particular miners, in changing contexts. Tomiyama began her career in the 1950s painting the worlds of miners in black and white. In later decades, she extended this subject to the memory of victims of various violent struggles in Asia, utilizing woodcuts and lithographs in the Käthe Kollwitz tradition in addition to her colorful oil paintings.8 The Politics of Memory in the 1950s In the context of the early 1950s, a responsible war memory emerged in the crucible of progressive democratic resistance that pitched citizen activists against an unresponsive or obstructionist conservative state. Workers demonstrated against what they saw as big capitalists once again enriching themselves at workers’ expense. A multifaceted peace movement exploded in protest not only in response to war in Korea but specifically against the remilitarizing Japanese state through the US-Japan Security Treaty. People with allegiance to Asia rallied against the government’s decision to throw its lot in with the United States at the expense of building harmonious relations with Japan’s neighbors, regarding this as a perpetuation of imperialist enmities. Some of this combined energy on the political Left reached a violent peak in May 1951 in what came to be known as “Bloody May Day.” Hanaoka Monogatari spoke passionately to the Japanese government’s evasion of responsibility as reparations payments were negotiated away under the San Francisco Peace Treaty that ended the US occupation, while leaving intact the US military presence and nuclear umbrella. Former forced labor czars then returned to public life, virtually all convicted war criminals had their sentences commuted, and the Chinese dead still lay unburied and unrecognized by the Japanese or Chinese governments. A particularly powerful print to this effect depicted three “Kajima bosses” celebrating their rehabilitation after the war while ignoring their responsibility for the crimes committed.

While many prints captured the desperate state of affairs in Hanaoka in ways similar to that of the 1930s Chinese woodcuts, equal if not greater emphasis lay on the positive energy of the victims’ solidarity and determination to fight for their liberation. In that senseHanaoka Monogatari bore greater resemblance to the post-1945 Chinese revolutionary prints both in theme and style. While repatriation of Japanese from China decreased to a trickle after 1947, the Chinese expatriate community in Japan joined forces with Sinophile Japanese and Zainichi Koreans concerned about SCAP’s and their government’s increasing hostility towards the Communists on the mainland. A variety of pro-PRC citizen organizations sprang up in Japan during this time, from the Overseas Chinese Association and the Chinese People’s Association for Promoting Democracy to academic and cultural organizations to promote the study of Chinese history and culture. The Japan-China friendship Association, founded in October 1950, served as an umbrella organization for these various groups. At around this time, the Overseas Chinese Association secured a copy of the Foreign Ministry report on wartime forced labor, which had been leaked by a conscientious Foreign Ministry official. Although the Association did not make this public (not, indeed, until 1993), it clearly used the knowledge gained from the report to exert pressure on companies like Kajima as well as local governments to return the remains of the dead to China and hold memorial services. The first such service for the Hanaoka victims was held in Honganji temple in Tokyo in November 1950 with Chinese, Korean, and Japanese in attendance. In March 1953, an umbrella organization called the Memorial Committee for Martyred Chinese Captives formed around the Japan-China Friendship Association, the Overseas Chinese Association, and the Japanese Red Cross to petition the government to return the remains of the dead and hold commemorative services. In July of that year, the government paid for the return to China of the remains of 551 Chinese victims of forced labor. During Buddhist memorial services in October, spokespersons of several pro-China citizen organizations delivered a joint statement of deep apology to China in the name of all Japanese, pledging themselves to work for lasting friendship between the two countries. The Chinese government, for its part, sent the remains of 2,472 Japanese killed in China to Japan while also pressing the Japanese government for an explanation of the forced labor issue, on which the Foreign Ministry stonewalled. Chinese demands for war reparations were equally unsuccessful. Nevertheless, in a remarkable move, the People’s Republic in 1956 released 1,017 of a total of 1,062 Japanese war criminals held in prisons in Manchuria after a short trial. Many of these soldiers had previously been in Russian captivity and had been extradited to China in the late 1940s. For almost ten years, they had undergone a type of re-education that confronted them with their individual crimes, explained those crimes in terms of Japanese imperialist aggression, and encouraged the prisoners to write confessions describing their crimes in detail.9 By releasing these prisoners, the PRC followed the example of the nationalist government on Taiwan (KMT), its biggest rival, which had pardoned all war criminals convicted by KMT courts in 1952. Over the next half century, through the Association of Returnees from China (Chūgoku kikansha renrakkai or Chūkiren), the repatriated war criminals publicized their personal roles in perpetrating war crimes and called for public atonement for Japan’s crimes and reconciliation. Their forthright testimony raised public awareness of Japanese wartime aggression. Their lifelong insistence on their own and their country’s culpability would be dismissed by conservatives as the result of Chinese “brainwashing,” but the fact remains that over the decades they played a crucial role in promoting critical war memory at the grassroots level throughout Japan.10 Chūkiren exemplified the pattern of citizens taking the lead in the public management of war memory and postwar responsibility in place of the government. There is no doubt that the PRC’s carrot-and-stick approach to war legacies was no less politically motivated than the Japanese government’s politics of refusing to address war legacies such as forced labor. Both served immediate political aims that stood quite apart from a moral imperative to demand the truth about past atrocities or take responsibility for them. In a very different way of dealing with convicted war criminals serving sentences in Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison, Japanese officials in charge of moving prisoners to the American-instituted parole system petitioned the U.S. Clemency and Parole Board on behalf of those convicted in the Hanaoka trial. They pointed to the fact that— given the Chinese politics of amnesty—had these men been convicted in a Chinese instead of an American court they would now be free. In the language of these petitions, moreover, not only had the perpetrators acted in accordance with admittedly unfortunate but “common and customary practices” during the war, but the government had appropriated for itself the work of public atonement that in fact had been carried out by citizen activists. [quote from NOPAR’s clemency petition for Fukuda Kingoro11 The Hanaoka war criminals, placed in the “hard-core” category by the Americans, were eventually paroled, but not until the war crimes trial program as a whole wound to an end after 1956. Recently released documents reveal that by the end of the decade, when the revision of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, major labor unrest, and Chinese reparations demands loomed large, Foreign Ministry officials moved to put an end to the discussions of Chinese forced labor generally. The Ministry flatly stated that all documents pertaining to this issue, including the Foreign Ministry Report, had been irretrievably lost. In this way, the government washed its hands of its responsibility to deal with this war legacy and instead left the job of commemoration and atonement to citizen groups. Neither the PRC nor the government on Taiwan pressed the issue after 1961, and in 1972 Zhou Enlai gave up China’s right to reparations in the Joint Chinese-Japanese Communiqué that paved the road to normalization of official relations. Meanwhile, Japanese citizen groups continued to dig up the bones of the dead, hold commemorative ceremonies, return the ashes to the bereaved families in China, and build memorials.12 Hanaoka Monogatari remained, for the time being, the only public narrative on Japanese wartime atrocities against Chinese (and Korean) forced laborers on Japanese soil. The Struggle for Compensation in the 1990s Official efforts to suppress information relating to the Hanaoka Massacre and its aftermath began to break down in the late 1980s. Japanese journalists, academics, lawyers, and citizen activists have since chronicled the facts in public discourse as part of a call for belated apology and compensation for victims. William Underwood, a former professor at Kyushu University and an expert on war compensation lawsuits, worked tirelessly to bring the issues to the attention of Anglophone readers since the 1990s. The following relies heavily on his work and that of Japanese and Chinese colleagues. First, a group of Hanaoka survivors in China organized to demand compensation from Kajima Corporation and worked with Japanese lawyers to press their case through the Japanese courts. This time, the impetus for putting issues of war responsibility on the public agenda came from outside Japan (albeit without Chinese government support) and tapped into existing progressive citizen networks in Japan. Second, this was part of a much larger, transnational, and indeed global movement to address heretofore neglected war atrocities through highly publicized demands for full disclosure of the historical facts, apology, compensation, commemoration, and public education. The urgency of this move towards historical restitution and reconciliation stemmed at least in part from the impending loss of the generation of survivors and witnesses, all of whom were of an advanced age. Third, public and private organizations collaborated in the early 1990s to turn up crucial government documentation on the wartime and early postwar handling of forced labor, most important being the 1946 Foreign Ministry Report. It gave much needed ammunition to the lawsuits making their way through the courts, created unprecedented public awareness of the issue, and moved the government’s war responsibility into the public limelight. The Hanaoka case proved to be a rare success story among the many war legacies taken up in Japanese courts since the 1990s, but the legal process it followed also exemplified a common trend among redress movements.13 In late 1989, Hanaoka survivors and bereaved families in China organized around the figure of Geng Zhun, the erstwhile leader of the Hanaoka uprising. They contacted Kajima Corporation through the mediation of two Japanese human rights lawyers and several academics in Japan involved in war responsibility issues. The result was a “joint statement” of the survivors and Kajima in July 1990, in which Kajima, with extensive interests in China and, therefore, powerful incentives to come clean, acknowledged its historical responsibility, apologized to the victims, and vowed to continue negotiations. The case nevertheless went to court when Kajima stonewalled on the survivors’ demands for financial compensation. On September 28, 1995 a suit was filed seeking 60.5 million Yen in compensation. First rejected in the Tokyo District Court because of the statute of limitations on forced labor, it received favorable rulings in the Tokyo High Court, which mediated a compromise settlement in November 2000 in which 500 million yen was to be shared by survivors and their next of kin. While Kajima did not acknowledge its legal responsibility to make amends, it agreed to set up the Hanaoka Peace and Goodwill Foundation, a trust fund used for memorial services and payments to survivors and bereaved families. The Foundation was managed on the recipient side by the Chinese Red Cross. The two parties also agreed on the establishment of a memorial hall, the Hanaoka heiwa kinenkan, which opened in April 2010.14 Among numerous Japanese forced labor compensation cases, Hanaoka remains perhaps the best documented and best managed. Early local efforts to keep its memory alive contributed to this outcome. The 1951 woodcut story of Hanaoka in historical and contemporary context impresses not only for its brutal candor, which the historical records amply confirm, but also for its creators’ keen perception of the larger processes and meanings of war and postwar responsibility then in the making. Hanaoka Monogatari was a product of its time, and its sponsor, the Japan-China Friendship Association, defined the contemporary context in the book’s epilogue as one of unprecedented collaboration between labor, peace, and pro-China movements actively resisting a government that seemed bent on reviving its anti-Asian, militarist proclivities. In keeping with this spirit, the first edition in 1951 did not mention the names of the artists who had created the prints and poems. One suspects that the disappearance of the original wood panels in the mid-1950s, most probably hidden by Maki Daisuke, may have had something to do with this. Hanaoka became the Japan-China Friendship movement’s first showcase of its political activism. Hanaoka Monogatari bridges the gap between the need for recording what happened in order to claim compensation for the victims and an act of registering moral outrage, ethical witnessing and mourning akin to some of the avant-garde art of the time. Indeed, the reader might very well linger over a print or poem in this book and feel its power on its own terms, quite apart from the politics of the past of whichHanaoka Monogatari was such a significant part. Franziska Seraphim is associate professor of Japanese history at Boston College and the author of War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005 (Harvard University Asia Center Press, 2006) She wishes to thank John Dower for his initiative to bring this work to public attention and his invaluable help in understanding woodblock print art at this time, as well as Richard Minear for taking on the translation and Mark Selden for bringing the project to publication. Richard H. Minear is professor emeritus of Japanese history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and editor/translator ofHiroshima: Three Witnesses (Princeton, 1994), Japan’s Past Japan’s Future: One Historian’s Odyssey (Rowman & Littlefield, 2011), The Day the Sun Rose in the West: Bikini, the Lucky Dragon, and I (Hawaii, 2011), and other works. He wishes to thank Franziska Seraphim for introducing him to Hanaoka Monogatari, Chisato Kitagawa for line-by-line explication of the text, and Fujita Shōzō of Hitachi for responses to specific inquiries. Notes 1 . Cf. Kajima history in English. 2 . Cf. essays by William Underwood, among them: “NHK’s Finest Hour” (Aug. 2006); “Names, Bones and Unpaid Wages (1): Reparations for Korean Forced Labor in Japan” (September 2006); and “Proof of POW Forced Labor for Japan’s Foreign Minister: The Aso Mines” (May 2007). 3 . In addition to Hanaoka Monogatari, Richard Minear has prepared translations of Hitachi Monogatari and Jōhō Monogatari. 4 On one side of the memorial are inscribed the characters for a “growing tradition of friendship” (hatten dentō yūgi), on the other side, “opposition against aggressive war” (hantai shinryaku sensō). On the back the inscription reads: “With the support of caring people from both Japan and China, we have erected this monument to friendship and will never again allow war between Japan and China. In 1944-1945, 993 Chinese, who had been brought here illegally under Japanese militarism, lived here in the Chūsan Dormitory at the foot of this mud-filled dam, abused and forbidden to speak their native language. On 30 June 1945, these laborers, as well as those who wanted to protect the honor of their fatherland, rose up as a group to at last oppose Japanese imperialism heroically. Here lie the remains of 418 people who gave their lives patriotically to this cause. We will forever remember this incident, our prayers never again to allow war between Japan and China are chiseled into stone for the grandchildren of both countries.” Quoted in Seraphim, War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005 (Harvard, 2006, p. 131) 5 According to Nozoe Kenji, the Hanaoka mine had put to work over the years approximately 300-400 Allied POWs (1944-45); 800 Chinese POWs (1944-45), 300 Chinese drafted workers (1944-45); 4500 Koreans (1942-1945); 600-800 reservists and volunteers (1944-45); 300 Japanese student soldiers and 1500 Japanese contract workers. 6 “Capitalists and reactionary bureaucrats in this country are working together mercilessly to sack admirable workers who are trying to rebuild a democratic and peaceful Japan. The number of violent incidents in which workers’ resistance is suppressed in a bloody manner is increasing by the day. If things are left untended, there is going to be World War III as they desire, and fascists will again turn us into slaves.” Quoted in Mari Yamamoto, Grassroots Pacifism in Postwar Japan: The Rebirth of a Nation, Routledge, 2004, p. 38 7 . Cf. Seraphim, “People’s Diplomacy”. 8 . Cf. “Imagination Without Borders”; Tomiyama’s “Prayer in Memory of Kwangju”; and Tanaka Nobuko,“Brushing with Authority: the Life and Art of Tomiyama Taeko”. 9 See Takahashi Tetsurō, Kaneko Kōtarō, Inokuma Tokurō, “Fighting for Peace After War: Japanese War Veterans recall the war and their peace activism after repatriation” (tr. Linda Hoagland). 10 . Cf., here. 11 “As for the numerous Chinese lives lost in misery at Hanaoka Mine, it has been taken by the Japanese nation as a blunder committed during wartime by the nation as a whole, and from such point of view, big memorial services were held at the mine as well as in Tokyo by the government and people of Japan, and the government has shown its sincere regrets in arranging safe sending home of ashes of the deceased. It is most ardently hoped that some sympathetic steps will be taken now for the subject prison inmates who had unfortunately taken part in this disastrous case.” (quote from NOPAR application for clemency, quoted in a summary of the “Application for Clemency for Fukuda, Kingoro” by the U.S. Clemency and Parole Board, 1952. RG 153, Clemency & Parole Board Files, Box 884, No. 331, US National Archives) 12 . Cf. photo of one of many Sino-Japanese Friendship memorials. 13 . For a narrative introduction of the lawsuit in English by one of the main attorneys involved in the Hanaoka case, see here. 14 . Cf., here. Parallel to this decade-long legal process, the Society to Think About Chinese Forced Labor published eight volumes of documents on the wartime and postwar history of the Hanaoka mine case from 1990 to 2001, including a special volume on reconciliation, followed in 2006 by the trial records of the U.S. Class B/C war crimes trial on Hanaoka. The Society maintains a useful website which includes Japanese documents and their translations into English and Chinese.

|

|||||||||

The Ballad of Hanaoka*

Translated by Richard Minear

|

* For best display, use a recent version of Chrome or Safari.

|

I single-cropped summers, lumbered winters;

sold my daughter but was robbed of my land.

Now that I’m homeless, where else can I go?

Hanaoka in the north: to Hanaoka, ho!

Azaleas smile so sweet each spring,

but for the last hundred years miners stagger and drop.

In the bowels of the earth, where treasure’s to find,

the bones cry out: the copper mine.

Every time there’s war, the miners’ ranks grow,

and so does the mine-owner’s purse.

The Hanaoka copper mine: Hell’s very worst.

* Titles link to the respective original Japanese text below.

|

It’s Hell, really, this mine.

Metal shit from the mine

buries paddy in metal shit;

angry farmers raised banners, of course,

protested the mine.

In the words of the song,

when they see paddy buried in metal shit,

wives and wild crows cry,

“All is woe!”

As I look at dead fields,

it burns inside,

boils up inside—the anger!

|

Time and again bosses beat the men

and shout their mantra—“More coal!” “More coal!”

But a man’s strength has its limits.

If you rake off rations in the mess hall

and don’t feed the men enough,

then of course they’ll totter.

All the more so the women, not up to this,

not to mention the pasty-faced merchants.

|

What’s more, girls dragged off

“For the country,”

naked, bare to the navel,

one small cloth hiding their fronts,

pushed ore carts in the mine:

How embarrassing!

How hateful!

Yet no matter how embarrassing, how hateful,

they couldn’t complain.

Behind them, the six-foot cudgels of the bosses.

The bosses didn’t have the feelings

human beings do.

|

Even the sick, home in bed,

were led off, tottering:

“Army orders,”

“Holy war.”

They gnashed their teeth in anger,

but for war profiteers

hot to make money,

it was water off a duck’s back.

|

Cave-in!

Cave-in at Pit #7!

Like balls rolling, miners came racing.

Weeping and wailing, families pleaded:

“I want my father’s body!”

“I want my son’s bones!”

What did the company men do?

The same as always:

at the memorial service, they doled out mere pennies.

The twenty-four men buried alive:

their bones are still underground.

May 1944, it was.

Yes, that’s when it was.

Even as the mine turns a profit,

bones long underground

cry out.

|

Korean workers—

farmers, too—were dragooned and brought here.

The Koreans

simply couldn’t keep silent any longer,

stormed en masse into the office:

“Raise our wages!”

“Give us full rations!”

In our hearts we really cheered for them:

Wow! Those Koreans sure are brave!

This when the rest of us couldn’t do a thing.

Treated so brutally, under cover of darkness

even the drafted workers*

began to run away.

* Presumably the Japanese workers drafted into mine work were the most experienced and capable and should have led the way.

|

This mine that produced copper,

that produced, too, the makings of gunpowder—

it was wartime, see, crazy,

Everything in turmoil.

Girls were dragged off,

students dragged off,

even town merchants dragged off:

All dragged off, their livelihoods wrecked,

and terrified by voices thundering:

“Expect to die ‘For the country’!”

* Not Korean or Chinese, but Japanese.

|

Day after day the trains carried ore from the bowels of Hanaoka,

and in the opposite direction, to the bowels of Hanaoka,

the trains carried people:

Farmers whose land had been stolen,

merchants whose businesses had failed,

people who toiled and toiled but couldn’t put food on the table.

The trains came, transporting them

to the bowels of Hanaoka

to work them ’til they dropped.

Among them all, we can never forget

the three trains

that brought the Chinese prisoners:

the first: July 1944

the second: May 1945

the third: June 1945.

|

How did Chinese get to Hanaoka? (1)

A Chinese prisoner speaks:

I was caught by the Japanese army

doing sabotage work.

At the internment camp they threw me into,

three thousand comrades, from kids to old men,

were bullied to within an inch of our lives

by the traitors who’d stolen our country.

Each day twenty comrades died.

Japanese devils raped every last female.

Two meals a day—sorghum;

a single well for all those people.

The hunger!

In the sizzling heat, the thirst!

|

How did Chinese get to Hanaoka? (2)

One day we were packed into freight cars—

cars labeled Beijing-bound.

We were packed so tight we couldn’t breathe,

and the weak comrades died before we got there.

Like fish out of water, we sucked air

through cracks in the car walls.

We drank our own piss.

|

How did Chinese get to Hanaoka? (3)

From our Qingdao—the port stolen earlier by Germany,

stolen now by the Japanese devils—

we were loaded aboard ship.

We were still hungry and thirsty,

but those who begged for water got booted overboard.

We licked moisture off the ship’s pipes.

Gasping for breath, we were brought to Japan.

This is the tale of the prisoners.

Bones rattling, wobbly,

they were brought here,

into the depths of northern Akita—to Hanaoka,

then thrown into

Kajima Construction’s Chūzan Dorm.

|

‘Chūzan Dorm’ may not sound bad,

but it was the Main Street of Hell.

There began the treatment, painful to watch,

of the nine hundred Chinese.

Day after day we averted our eyes.

If their ranks were a bit sloppy

on the road to the worksite,

they’d be abused, knocked down with cudgels yea thick,

half-murdered.

They were led by veterans of the anti-Japan war,

men of the Eighth Route Army, cream of the cream,

so Japanese militarists and the Wang regime agreed

to bring them here

to kill their morale.*

* Eighth Route Army: the forces of Communist leader Mao Zedong; Wang regime: the regime of Wang Jingwei, sponsored by the Japanese.

|

Going outside at night—strictly forbidden;

same clothes, summer and winter,

working barefoot in icy mud

in the bone-chilling cold here in the north;

starving to death with a rattle, freezing to death;

no longer able to move but given a shovel—

take a moment’s breather and get knocked to the ground;

once down, they’re goners.

Until nine at night,

sometimes till midnight,

we could hear them driven on

by swords, cudgels, shouts.

|

No matter how parched their throats,

they weren’t allowed even one gulp of water on the job.

No matter how they begged, it wasn’t allowed.

Working on hands and knees here

along the Hanaoka River,

under eagle-eyed guards watching lest he drink,

utterly unable to resist, he swallows one gulp,

and suddenly cudgel, boot, scabbard

hit, kick, strike all over—

shoulders, hips, back.

They’re gonna kill him:

that’s what everyone thought who saw it.

|

Breaking the Valley to the Hoe

Even those who’d fallen sick

were given shovels and sent off

to break barren Ubasawa to the hoe.

Look! Even if for a moment, exhausted,

he rests on his shovel, from behind—

Whack! Whack!—

the cudgel snarls.

Fields bloomed fresh and green,

but what a shame!

They worked for dear life to grow the food

but got not a bite of it to eat.

|

Ground-up acorns, apple peels, rice bran, water:

even horses wouldn’t eat the stuff

they gave these men to eat.

What on earth did the bosses do with the rations?

Seems the Kajima Construction bigwigs sold them on the black market.

So the men ate trampled apple peels,

ate up all the roadside weeds;

some ate poisonweed and died.

Those still, amazingly, on their feet,

utterly malnourished,

clenched their teeth

held on, survived.

To what end?

Ah, to what end?

|

There were bad guys here, too—

while their buddies all suffered,

while their buddies all held on,

they were like thieves.

They curried favor with the bosses, read their moods,

grew fat from the leavings

of those who took a rake-off

from the sake and rice rations,

made their buddies suffer, strutted about.

|

“Never seen it so bad!”—

Father gave them willow leaves.

Everyone was eating weed dumplings.

Father, too,

must have been eating willow leaves.

Those who labor are all one;

poor people are all brothers.

Others avoided the super’s watchful eye

to bring them weed dumplings.

Miners shared their ration of hardtack with them,

and even the students gave them tea.

And

we learned Chinese words and songs

—at a time when the company men were eating meat

and pouring into the ditch

the hooch they couldn’t drink up.

|

A song the Chinese taught us:

Arise, the people that won’t become slaves!

Build the Great Wall with the blood of the people—

the Chinese nation is in danger.

Raise the cry!

Arise! Arise! Arise!

(tune: Brave Soldier March)*

* This is now the Chinese national anthem. I have stuck close to the Japanese for the first five (of nine) lines; this translation is from nationalanthems.us:

Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!

With our flesh and blood, let us build our new Great Wall!

The Chinese nation faces its greatest danger.

From each one the urgent call for action comes forth.

Arise! Arise! Arise!

Millions with but one heart,

Braving the enemy’s fire.

March on!

Braving the enemy’s fire.

March on! March on! March on!

|

Despite everything—

they didn’t lose heart.

Though hungry, starved, murdered,

they didn’t lose heart.

So thin their bones showed, they all sang

from throat, from chest.

They all sang, with power,

songs of changing the world,

of the hardships of working people,

of liberation.

|

The sound that day—

what did they think when they heard it?

Summer 1945:

B-29s flew over the mine and off,

trailing their piercing whine.

The men of the Eighth Route Army

who led the Chinese prisoners—

cream of the cream, whose task was to root out

the suffering of laborers, farmers:

their bright eyes glinted

as they followed the sound—

“The time has come!”

|

Psst: The time has come!

This is why we’ve put up with

being reviled, called horses, cows, beasts,

being kicked, beaten.

Now’s the time

“To overthrow Japan’s emperor system,

stop aggressive war,

set the people of Japan free—

for world peace,

for human happiness.”

They must have remembered

the battles they’d fought in their own country,

then—

made battle plans, I hear,

in secret gatherings nightly.

|

First of all,

they organized a main force,

cream of the cream,

with bodies able to take the worst

and fighting wills of steel,

and appealed, too, to the workers of Japan

to join hands and rise up in final struggle

against the common enemy.

We all gathered what little food we had

to give them.

|

Why have we crossed the ocean to Japan?

Why have we put up with being treated

worse than dogs?

To rid this world of those who would destroy us Chinese,

who feed on our Japanese brothers,

who drench the world in blood:

Hitler, Tōjō, and their ilk—Fascism’s gods of death.

That’s why.

Let’s light a beacon fire for the new Japan!

Let’s herald the dawn to laborers and farmers!

Let’s awaken them to their own strength!

In order to stop the war, overthrow the moneybags and the military clique,

and make this a peaceful, happy land.

Hitler is beaten.

The time is near when the mighty aid of the Soviet Union

will appear in the East, too.

The bright day of victory is near.

That’s how they encouraged their comrades

and brought life to sunken eyes.

|

Look out!

At this eleventh hour, with lives on the line,

one guy just snuck off!

Do in that worm!

That rotten traitor,

scared to die,

has sold out the group’s admirable plan.

The cat’s out of the bag!

|

Not a moment to lose!

Everyone, on your guard!

No more planning. Time to act!

Raise the anti-Japan flag of the Chinese people!

|

Blood Sacrifice on the Street Corner

We’ll show you! This is the moment for blood sacrifice—

first, the traitor to the people,

who kicked and beat our buddies,

even sold out our noble calling!

Eat this pick!

And next?

The bosses, running dogs of the military clique,

who stole our food and killed our buddies!

|

Still,

among the Kajima bosses

was one

a bit better,

a bit more human,

and the prisoners singled out

that boss

and let him flee.

|

The company bosses rolled their eyes, absolutely astonished

at the whispered report of the traitor.

In a fright

the prefecture’s chief of the special police worked the phone

and went to the site on the double.

In the middle of the night, orders flew

to the prefectural police.*

* The “special police” (Tokkō) were national police, in charge of ideological purity; the prefectural police were ordinary police.

|

“They’re armed!”

“They’re uppity, those Chinks.”

“Kill ‘em!”

Aping the officers,

officials and landlords filled our minds

with malice.

Wholly taken in by their glib talk,

you and I

took bamboo spears, drew swords,

swaggered into the woods,

took our stations.

|

Officers and company bosses

rounded up Japanese laborers

to comb the hills.

The Koreans they locked up

in the pit, willy-nilly.

To those no-good types,

the Koreans were

“malcontents.”

When will it explode?

—the bomb of liberation!

|

We stood at attention as we were trained to do:

reservists, Yokusan young adults brigade,

women’s association, air raid wardens.

The officer drew his sword, bellowed,

“Just like those dirty Koreans in the Kantō earthquake,

the Chinese prisoners plan violence.

They’ve already massacred children of the emperor.*

Looting, arson, murder—

they’re violent troublemakers who’ll stop at nothing.

Take your stations!”

* Reservists (zaigo gunjinkai): the single most influential local organization of males between the ages of 20 and 40, including veterans and those who had not served; “Home Military Association might be a more accurate translation. See Richard J. Smethurst, A Social Basis for Prewar Japanese Militarism: The Army and the Rural Community (Berkeley: University of California, 1974). Yokusan: the youth offshoot of the one-party party, the wartime Imperial Rule Assistance Association. In 1923, at the time of the great Kantō earthquake, Japanese vigilantes massacred Korean residents on rumors—inaccurate—that Koreans were looting, poisoning wells, and killing Japanese. Children of the emperor: wartime language for “Japanese.”

|

The Chinese tore down phone lines,

seized weapons,

and set off.

Scattering for now

to bide their time:

Head for the woods! For the shelter of the woods!

In the pitch black, feet feeling their way,

voices raised in liberation songs like a far-off ocean’s roar,

they dispersed.

|

Main force: to the south, to Ōdate:

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp

Gunbarrels reflecting the stars,

spades glistening with dew.

eyes open wide,

steely:

to Shishigamori.

to Shishigamori.

|

The Rock Fight at Shishigamori

Shishigamori: the waves and the shouts of the Chinese

as they made their way into the woods,

signals—were they not?—

to us workers, farmers:

“Rise up together for the liberation of the Japanese people!”

Egged on by kempei, cops, capitalists, landlords,

we pelted them with rocks:

Rat-a-tat-tat-tat.

From the woods, too, rocks came flying,

and we were no longer brothers:

“Damn you! Chinks, go to Hell!”

Amazingly, the rock fight went on for two days.

The poor Chinese.

The sick Chinese.

The songs of liberation at the top of their lungs didn’t stop,

but the rocks that came flying gradually lost their force,

and the midsummer ruckus at Shishigamori weakened and died.

|

Ah, that leader—

even reduced to skin and bones,

that steely leader knew no fear.

Still—he couldn’t win.

On that pathetic battlefield,

the men dropped, were captured one by one.

He fought, fell back, finally disappeared from sight.

|

We saw it all—

the young Chinese brought in

like game on a pole,

bones broken, arms wrenched off:

not a single one groaned.

The men who brought them to the police station in Ōdate

boasted, “You’re dogmeat stew.”

The landlords’ fear, their hateful looks,

the derision of the kempei.

Tied up, unable to resist, again and again

they were stabbed with bamboo spears, struck with cudgels.

The gleam in their eyes then,

their defiance,

their contempt, as if for dogs,

their silent, shining eyes.

|

Community Hall square:

this-worldly Hell.

Barely alive, the Chinese

were forced to kneel on triangular rods,

bound two by two in the shit and urine;

in the burning noonday sun

struck by rifle butts, cudgels, the sheaths of swords!

Three days with no food or drink:

we watched

with unseeing eyes.

|

Were they rotten fish?

Dead horses?

Still bound in twos,

they were kicked off the trucks in a heap.

Hanaoka Community Hall square

is stained even now with their blood.

Their blood will never be wiped away.

So long as two-legged beasts still exist in this world,

even now, in that square the stains remain.

|

Taking pity,

stealthily, a woman rolled weed dumplings

toward their knees.

One Chinese gathered them

with his knees.

Suddenly a kempei kicked him over,

struck her—Pow!—in the face.

|

From inside Community Hall,

blood-curdling groans.

Dull thuds.

Strung up by their thumbs

from wire that twisted and twanged.

Flesh peeled off, finger bones remained.

When we asked them later,

they said their bodies went numb.

|

The corpses of the murdered, over three hundred of them:

after three straight days of interrogation

in bright midsummer sun—

covered with pitch-black flies

so heavy with blood they couldn’t fly;

At night ravenous dogs

sniffed, nosed about the bodies.

|

In the fields of Ubasawa, even now,

bones surface all the time.

As rain erodes the dirt,

bones surface, flesh rotted off.

The bones of those who died

at the hands of Tōjō, Hirohito, their underlings

are exposed to rain, to wind—

as if to say, “This country never lacks

for those who torment and exploit the people.”

We’re still finding

evidence of the cruelty

of capitalists, landlords, police.

|

The crazy war ended.

Japan’s military and emperor

who’d kept deceiving us—“Victory! Victory!”—

finally went belly-up.

B-29s dropped goods

to American prisoners

and whined off.

Then for the first time the prisoners

looked alive.

Yet: as always,

the Chinese prisoners got nothing,

still used grass thread

to sew up their rags.

|

Kajima Construction: brazen and cruel to the very last,

greedy to the very last.

The war ended.

Japan lost.

Those guys put on know-nothing faces,

trying now as before

to trick the Chinese.

They won’t get away with it!

The Chinese stood up.

They stormed Kajima Construction.

“Stop this nonsense!

Treat us like human beings!

Send us back to China right away!

Hand over the war criminals who bullied us,

and have the blood of our brothers on their hands!”

|

White with fear, the dogs—capitalists, landlords—

went crying to Mr. America.

Kajima bosses, chief of the Kempeitai,

governor, police chief, chief of the thought police,

leaders of the reservists’ association and the yokusan youth group—

all alike bloody murderers:

they did it, but what happened to them?

Underlings were punished only for minor war crimes;

big-shot war criminals made big bucks once again.

Hanaoka today is the military base of a foreign country.

Those guys are already preparing

for the next war,

planning to turn us laborers and farm people

into slaves, human bullets.

|

The song to the noble sacrifice of those Chinese

who made the bowels of the earth tremble

shook us to our very souls.

Finally we woke up,

we laborers and farmers raged,

and terror-stricken, the war criminals—

the Kajima bigwigs—

put on pious faces.

furtively collected the bones—

like gravel—into gas cans,

and erected a flimsy gravemarker

at the edge of the field.

|

Learning from The Example of Those Who Went Before

Songs of liberation were sung loud and clear.

They were sung

from the bottom of the hearts

of surviving Chinese and Koreans.

We too sang,

joining our voices to theirs.

From that point on

we began to fight

company, landlords, government.

In both the February first fight

and the bloody fight over Imperial Oil,*

our martyrs learned from their example

and fought.

Dig up the bones of all the martyrs;

charge and punish every last war criminal;

preserve and tell the heroic deeds of those who died:

that’s our job.

* February 1, 1946, was the date of a scheduled general strike that the American Occupation forced Japanese labor to call off.

|

One wife wept:

“They gave me

a box of my husband’s ashes,

but it held no ashes.

The Chinese were lucky—

they actually got ashes.”

On the train,

she looked at the boxes of Chinese ashes

and wept.

|

It’s true—

people from the country where working people hold power

searched diligently

and gathered up the bones of their brothers.

But look: with mere slips of paper, Japan’s emperor and military

drafted men off to war,

then left their bones to the elements, to bleach.

You! Tell your wife—

“The Chinese held strong

right through the funeral.”

Yes, you and we

must follow their example!

The spirit of the murdered

must be transmitted to all of us Japanese

And we must rise up!

The time has come to strike off the shackles of reaction

and let the sun shine

on the people of this land.

|

Who were the chief mourners at the funeral?

The surviving Chinese brethren.

Hanaoka parents and wives who had had to eat weed dumplings.

But not only they—the true chief mourners

were five hundred million Chinese compatriots

and eighty million working people of Japan.

And not only they—

but the people of all Asia, the whole world,

who defend peace and hate war,

united, fighting to prevent them from making Japan

a springboard for aggressive war and the source of Asia’s disaster!

Such cruel events must not happen again!

Follow their example and fight!

Two-legged dogs rose up in anger at their voices,

wouldn’t let them sing the anthem at the funeral,

wouldn’t let them talk about the Chinese.

With pistols and cudgels

they chased off laborers

pledged to the Red Flag.

|

When surviving Chinese comrades

who’d suffered together

and fought together

tried to speak of their murdered brethren,

Chiang Kai-shek’s hirelings lunged

and suppressed them.

Following the example of those who went before,

Japanese and Chinese struggled, weeping, trembling in fear,

but the bullies shoved them away,

did not let them speak.

Who made them do it?

We know!

See—they’re all in cahoots!

We know!

|

The Rage of the Chinese People

Learning of the martyrs of Hanaoka,

the Chinese people shook with rage,

struck the ground, rose up.

Guo Moro cried out,

“The four hundred martyrs of Hanaoka are only a fraction of the total.

The martyrs number ten times four hundred,

a hundred times four hundred! …

Leave no stone unturned in searching out the criminals

who murdered our comrades.

They must be punished.

Repay blood with blood to root out militarism,

the enemy even now of world peace….”

Note: The writer Guo Moro was Vice-Chair of the Chinese Peoples’ Republic and Vice-Chair of the World Peace Association Committee

|

Wives, parents—never forget!

Children—engrave this on your hearts!

From olden times to now, the bones of our brethren

have lain in Pit #7.

We still see them even now—brethren whose voices are blocked,

whose hands are bound,

who totter, consumptive,

adrift in Akita, in the depths of the north,

and one after another are murdered.

Who’s murdering us?

We know who!

We’re prisoners, too—it’s our own country,

but we can’t get out of line,

are forced to eat weeds,

are ill-treated by a foreign country—

just like the Chinese who died.

Learn from their example!

Never forget Hanaoka!

The Hanaoka Incident is an incarnation, as it were, of the evils of militarist Japan. To investigate it thoroughly and to extirpate the rotten dregs of old Japan unearthed in the process is to lay the cornerstone of true friendship between Japan and China. To leave the incident vague is to nourish the germ of militarism; doing so will become the cause of another fierce war.

This illustrated book has been created, by people who love peace, love Japan, and aim for eternal Japanese-Chinese friendship, to create a great people’s movement. In seeking the truth about this incident, which caused so much hardship and seemed about to be buried in oblivion, we studied it and studied it; in the effort to give it expression as a truly living work of art, we argued and revised for all we were worth. This book was supported by the power of the Japan-China friendship movement that has arisen between the 40,000 Chinese who reside in Japan and the Japanese people; it has been supported also by miners, woodsmen, farmers, and democratic groups in Akita, where the incident took place, and by their activism; it is the result of a group effort by friendship movement people, artists, poets, writers, musicians, and others. A project that opens up a new direction in the world of art movements, it adorns one page of the art history of Japan.

We wish to thank each person who took part in bringing this difficult, epochal undertaking to fruition, and we hope fervently that each and every reader will participate in a great people’s movement that will carry this illustrated book into every nook and cranny of Japan.

May 30, 1951 Literary Section, Japan-China Friendship Association

|

米わ一作ひとさく 冬ふゆばわ山子ごよ 春にや つつじも につこりさくドモ いくさのたんびに ふくれてふえたワ 地ごくサ まるで この山ア たんぼうずめた カナくそみたバ 死んだ田んぼを ながめていたバ なんばカントクがぶつたたいたとて そのうえ なんぼ「くにのため」だとて からだわるくして うちで休んでいるものまで ラクバンだあ! 朝鮮のはたらき人つど―― あかがねのとれる この山ア まいにち まいにち この花岡の地のそこの そのうちでも おらだちのわすれていけねえのわ 中國の人がたどうして 中国のホリヨのはなしだスー おれわ破かい工作のとき 二度のコウリヤンめし 中國の人がたどうして ある日 貨車かしやにつめこまれ―― 中國の人がたどうして むかし ドイツにぬすまれ 今でわ これが ほりよのはなしだス 中山寮ちゆうざんりようたち 人ぎきもええが 夜の 外出わ かたくとめられ こうして 夜わ九時になり どんなに のどがつかえても 病氣になつた 人がたも 畑わ あおあお みのつだども いのちがけのしごとした あの人がたの ドングリの粉こ リンゴのカス ヌカと水 みさげた奴が ここにもいたど―― 「そんな むごいことみていられねえ」 あのひとがた おしえてくれた唄 たて どれいとなるな人民 人民の血で きずこう萬里ばんりの長城ちようじよう 中華民族 いま危機ききにあり おたけびあげよ たて たて たて―― (義勇軍行進曲) それでもなア―― あの時 あの音を (時がきた!) まンず なにより おれたちわ なにがため この日本にわたつたか? 日本の世なおしの のろしをうちあげよう ヒトラーわ つぶれた あの人がたわ なかまを こうはげました 氣をつけろ! もう一刻もひまわない! みんな ぬかるな! けいりやくはやめて 總けつき 抗日中国人民の旗をたかく! 思いしれ―― 血まつりの一げきは したどもシヤ うらぎりもののささやきに 「武器ぶきもつとるド」 將校らと会社わよ しこまれた とおり 立ちならぶ 電話線をひきちぎつた 主力部隊わ 南え 大館だてえ あきば山さ わけいつた中国の人がたの けん兵 巡査しゆんさ 資本家しほんか 地主らにケシかけられて よくまア 二日もつずいた石合戰よ ああ その部隊長―― この部隊長わ 今も生きのこつて 中国にいるド おら達だ みた―― 共樂館きようらくかんまえの ひろばわ くされ まぐろか あまりの いとしさに 共樂館きようらくかんの中からわ 殺ころされた三百あまりの死体 ウバサワの原つぱにわ いまも まもなく バカないくさがおわつた したども―― どこまで ずうずうしく むごたらしく 青くなつた資本家しほんか 地主ぢぬしの犬ども 地のそこゆるがす 解放かいほうのうたが たかくつよく うたわれたス 二・一のたたかいでも 骨ほねばこ ンだす おめえ 嬶あはさいつて呉けれ―― この葬そう式のも主はだれか? そのこえに ふるえ上つた犬どもわ いつしよにくるしみ 花岡のぎせい者のことしつた わすれるな 嬶あは 親どどだち 七つ館だてにわ むかしから いままで 見ならわずにか! 花岡事件は、軍國主義日本の罪惡のかたまりのようなものである。これをてつてい的に追究し、えぐりとることは古い日本の腐つたカスをなくして、日本と中國のほんとうの友好をきずくいしずえである。これをあいまいにのこしておくことは、軍國主義のばい菌をつちかつておくようなもので、ふたたびおそろしい戰爭をひきおこすもとになる。 一九五一・五・三〇 日本中国友好協会文化部 |