Israel Annexation Plan: Jordan’s Existential Threat

Jordan is being forced to confront a new reality with alarming cartographic and demographic consequences

More than any other Arab state, Jordan’s past, present and future are inextricably linked to the question of Palestine. Jordan’s emergence is an outcome of British imperialism, which imposed the infamous Balfour Declaration and the Zionist settler-colonial project on the indigenous population of Palestine and the region.

Settler-colonialism is the essence of the question of Palestine. All else is derivative. Jordan emerged out of this historical reality, and therefore, its present and future will always be subject to it.

The founder of present-day Jordan, Emir Abdullah bin Al-Hussein, successfully carved a new sovereign space in Transjordan. But this was only possible because of his cooperation with British imperialism and “collusion” with Zionist settler-colonialism. This tacit relationship resulted in mutual restraint between Jordan and Israel, even during their direct military confrontations.

National security interest

In 1994, Jordan and Israel signed the Wadi Araba peace treaty, turning their tacit understandings and secretive relationship into an official peace between the two countries – even if an unpopular one. This peace treaty would have been inconceivable without the 1993 Oslo Accord and the implied promise of Israel’s withdrawal from the West Bank and Gaza, which were occupied in 1967 from Jordan and Egypt respectively, to establish an independent Palestinian state.

Land repatriation and Palestinian statehood hold a high national security interest for Jordan. Only the achievement of these two conditions can halt the border elasticity of the Israeli state and its expansion eastwards, which poses grave geographic and demographic threats to the Hashemite kingdom.

Besides the strategic significance, a Palestinian state would allow a substantial number of Palestinian refugees displaced in 1967 to return to the West Bank, in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 237.

Yet, not only have neither of the two conditions been realised, but regional and international political dynamics have changed since 1994. In Israel, the political landscape has dramatically shifted to the far right, fuelling the settler-colonial practice of creating “facts on the ground” that make the prospect of Palestinian statehood and self-determination via the “peace process” a remote fantasy.

The political and material developments on the ground are complemented by complex regional and international dynamics. In particular, the Trump administration has taken a new approach towards most international conflicts, especially in the Middle East.

The Trump-Netanyahu plan (aka “the deal of century”) for Israel-Palestine promotes Israeli colonisation/annexation of the West Bank and sovereignty over the entirety of historic Palestine, as well as the Syrian Golan Heights.

Shifting geopolitics

Even worse for Jordanians and Palestinians, this plan enjoys the support of influential Arab states, especially Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have stepped up their political rapprochement and normalisation with Israel.

The EU, a staunch supporter and sponsor of the so-called peace process and two-state solution, failed not only to reach a common position on the US plan, but also to condemn Israel’s plans to officially annex any part of the West Bank.

Amid the changing international and regional politics, Jordan’s alliance with the US and EU has been a letdown. Jordan has become a victim of its own foreign and security policy, which has grown interlinked with the US and, more recently, the EU.

While half of this alliance, the US, is promoting Israel’s annexation and sovereignty over Palestine, the other half, the EU, is unwilling to act decisively.

The annexation is planned to take place while the entire world, including Jordanians and Palestinians, and the media are exhausted by the coronavirus pandemic. It provides the needed distraction for Israel to complete the annexation quietly, without effective local and international scrutiny and resistance.

Covid-19 has further entrenched the nationalist-driven trend in the Middle East. Even before the outbreak, the Arab world was consumed by domestic concerns, showing few qualms about the Trump-Netanyahu plan or recognition of Israel’s sovereignty over Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.

Israeli expansionism

The feeble Arab (including Palestinian and Jordanian) and international response to the US recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and the relocation of the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, has encouraged Israel and the US to press ahead and turn Israel’s de facto sovereignty over all of Palestine into de jure.

While this is all illegal under international law, it is a mistake to believe that empirical reality and time will not deflect, strain and fractureinternational law and legality.

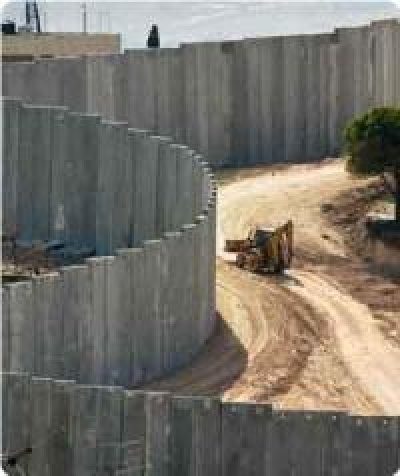

Since 1967, the Israeli strategy has pivoted on two parallel components: empirical colonisation on the ground, coupled with the facade of a “peace and negotiations” public relations campaign to obfuscate the settler-colonial structure and market it to the international community, as well as Arab regimes.

With this strategy, Israel has expanded in the region both territorially, by de facto taking over Arab land, and politically, through overt and covert relations with most of the Arab states.

Only formal territorial annexation and gradual de-Palestinisation remains. The formal annexation of the West Bank, especially the Jordan Valley, officially torpedoes the century-old Jordanian foreign and security strategy of cooperation with its imperial patrons (Britain, then the US) and the Zionist movement, which evolved into a Jordanian-Israeli peace with an expected Palestinian buffer state between the two.

Another ethnic cleansing

It also puts Jordan face-to-face with a new reality with alarming cartographic and demographic consequences. The chances of another ethnic cleansing become a palpable prospect under the formulae of official annexation and a Jewish statehood in the entirety of Palestine, as articulated in the 2018 nation-state law meant to ensure a Jewish majority.

This is very much tied in with Jordanian fears grounded in previous (1948, 1967) and current experiences of forced migration in the Middle East. Against this backdrop, another ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, forcing a large number of Palestinians to flee to Jordan, is a real possibility. The transfer and elimination of Palestinians from Palestine are embedded in the settler-colonial structure of the Israeli state, which looks at Jordan as their alternative homeland.

While another population flow would be catastrophic for Palestinians, it would also adversely affect Jordan’s stability and future.

Beyond annexation, the Hashemite regime is witnessing a contestation of its custodianship of the Muslim and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem, which constitute a significant source of legitimacy for the regime. Even on this matter, the US plan unequivocally appoints Israel as the “custodian of Jerusalem”.

After five decades, Israel’s grip over and presence in the West Bank is ubiquitous and entrenched. Most of the West Bank is empirically annexed and Judaised, especially the Jordan Valley, Greater Jerusalem, parts of Hebron and Gush Etzion. The pretence of the peace process and negotiations has thus become superfluous.

‘Considering all options’

Only against this background may one understand the depth of the trepidations that underlie the warning of King Abdullah II that the Israeli annexation will trigger a “massive conflict” with Jordan and that he is “considering all options” in response.

This warning does not reveal a strategy to respond to what constitutes a “direct threat to Jordan’s sovereignty and independence”, as the former foreign minister of Jordan, Marwan Muasher, put it.

It displays, however, the difficult decisions that have to be taken. Indeed, King Hussein was prepared to discontinue the Jordanian-Israeli peace treaty had Israel refused to supply the antidote for the poison its agents had used in an attempt to assassinate Khaled Meshaal, the former head of Hamas, in 1997. It remains to be seen whether the termination or suspension of this treaty and the realignment of alliances are currently options for Jordan.

The Jordanian response to Covid-19 has generated a unique, popular rally around the state – a perfect opportunity to conduct serious reforms to stamp out corruption and involve citizens in the decision-making process, in order to forge a nationally grounded response to Israel’s planned annexation of the West Bank.

Historically, the survival of the Hashemite kingdom has been at stake several times. But today, Jordan finds itself in an unprecedented political, security, economic and health emergency.

Whatever domestic, economic and foreign-policy decisions – or indecisions – that Jordan takes are likely to leave a long-lasting mark on the future of Jordan and the question of Palestine. Such existential decisions must be collective, with broader national consensus and real citizen participation.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Emile Badarin is a postdoctoral research fellow at the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) Chair, College of Europe, Natolin. He holds a PhD in Middle East politics. His research cuts across the fields of international relations and foreign policy, with the Middle East and EU as an area of study.