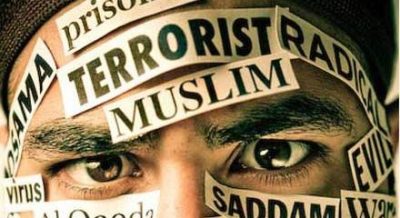

“Islamic Fundamentalism”: Unraveling a Vague and Ambiguous Term Used by Western Mainstream Media Against Islam and Muslims

Islamic Fundamentalism: A Misnomer

The term “Islamic fundamentalism” is definitely a misnomer. The term “Islamic fundamentalism” has not been derived from Islamic Scriptures, nor does any group of Muslims utilize this appellation of ‘Islamic fundamentalists.’ This term is just a misappropriation of the modern Western religious term “fundamentalism” to Muslims. The term “fundamentalist” was used by American religious sociologists to refer to Christians who believe in the literalist interpretation of the Bible—and as such in its original contextuality cannot be used for Islam or to Muslims.

From the definition of religious sociology, the term “fundamentalism” means giving emphasis on strict adherence to the fundamental or essential principles of any belief system. The term was originally applied to some ultra-conservatist Protestant Christian theologians in the United States in the early 1900s. They published a series of monographs between 1909 and 1915 called The Fundamentals of Faith: Testimony to the Biblical Truth. In these monographs, they defined what they believed to be the absolute “fundamental” or essential doctrines of Christianity. The core of these doctrines was the literal interpretation of the Bible. Those who supported these beliefs during the so-called Anti-Modernist debates among American Protestants in the 1920s came to be popularly called “fundamentalists” (See Dwight L. Moody Handbook of Theology, under the entry “Fundamentalism”. Chicago, Illinois: Moody Publishers, 1996.).

Academically speaking; for the sake of clarity and in order not to put Islam in a derogatory and pejorative manner, it is preferable to use “violent extremism” rather than “Islamic fundamentalism”. There are certain religious academics and sociologists within Islamic Studies who take the word “fundamentalist” in its literal sense of laying emphasis on the basic and essential teachings of Islam.

Thus, attaching importance to the basic or fundamental teachings of Islam is to fulfill the very demands of the Islamic faith. That is, if one takes fundamentalism in its strict literal linguistic sense, then it should be the same basic teachings of Islam as emphasized in the Islamic scriptures themselves. The essential teaching and ultimate concern of Islamic faith is monotheism.

The central focus of Islam is submission to the One God (tawhid). This is to believe in One God; loving and worshiping Him alone. The next fundamental teaching of Islam is adhering strictly to justice in one’s dealings with fellow human beings (huquq-ul-ibadh), returning good for evil, being kind and compassionate to one-and-all, taking care of God’s creation are essentially the very fundamentals of Islam and anyone who holds to these set of beliefs and praxis of Islam are fundamentalists in the literal linguistic sense of the word “fundamentalist”; and they are peace-loving not as what the Western mainstream media would like to portray fundamentalism as essentially violent and terroristic (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. Non-Violence and Peace-Building in Islam. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2017; pp. 7-15.).

Two Typologies of So-called “Islamic Fundamentalisms” Which the Western Mainstream Media Failed to Distinguish in Their Reportage

It is indeed unfortunate that the term “Islamic fundamentalism” was applied by sociologists of religion to Islamic movements beginning in the 1960s. However this term was not used for Muslims in exactly the same sense as it was applied to Christians. The term “Islamic fundamentalism” is applied to two different kinds of movements. One is the type which is essentially religious, one that advocates a return to the pristine fundamentals or essentials of the Islamic faith, for instance, those defined by the revivalist Muslim jurist and theologian, Hazrat Ibn Taimiyyah in the fourteenth century CE at Hijaz Province in the Arabian Peninsula. The other kind is essentially political and militant like that of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt (Ikhwanul Muslimun fi Misr), with an avowed goal of bringing about political revolution in Muslim countries (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, What Is “Islamic Fundamentalism”. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2004; pp. 14-15.).

The aim of the first form of Islamic fundamentalism, e.g., that of the Muslim revivalist theologian Hazrat Ibn Taimiyyah is to put an end to non-Islamic accretions and innovations (bid‘ah) in religious matters and to replace them with the Sunnah (or practices of the Prophet Muhammad), which is the fountainhead of the Islamic Shariah (Divine Law). The aim of the second form of fundamentalism is basically political and militaristic thereby striving to form a quasi-political movement, like the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt (Ikhwanul Muslimun fi Misr), which aims to put an end to non-Islamic political government in Egypt and replace it with an Islamic State ruled by its own interpretation of the Shariah(Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, What Is Islamic Fundamentalism. Op.cit, p.17.).

According to Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, Western sociologists of religion and Western mainstream media were not able to make clear distinctions with respect to the avowed goals of these two entirely different types of so-called “Islamic fundamentalisms”. Deeper analysis will show that both forms or types of so-called “Islamic fundamentalisms” are totally different from one another in terms of utilizing violence and armed militancy to further their aims.

For the first form or type of Islamic fundamentalism which is the revival of and return to the pristine tenets of Islamic faith, the sphere of the struggle against un-Islamic innovation (bid’ah) is confined only to matters of Islamic belief and worship. Violence does not, as matter of necessity, accompany movements of the first type of fundamentalism. Furthermore, it is aimed at and concerned with the internal reform and spiritual revival of Muslims. Thus, in their activities, the possibility of coming into conflict with non-Muslims is nil in the first type of the so-called “Islamic fundamentalism.

However as far as fundamentalism of the second kind is concerned, which virulently aims to topple secular regimes and set-up Shariah compliant ones, it has been directed from the very outset against political rulers in Muslim dominated countries, and whether the inevitable confrontations have been with Muslim or non-Muslim rulers, by its very nature such a movement has demanded the use of armed conflict and violence (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, The Political Interpretation of Islam. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2015; pp. 14-25.). It is here within the second type of so-called “Islamic fundamentalism” where self-serving and skewed interpretations of jihad have been utilized by the fundamentalists who justified violent extremism to further their political intents and agenda.

Understanding Authentic Jihad in the Context of the Qur-an

At the very beginning of the Qur-an, the first statement reads: “In the name of Allah, the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate.” Throughout the whole Qur-an, this verse is repeated for no less than 113 times right at the beginning of every chapter, except one. Even one of God’s names is As-Salam (Peace). Moreover, the Qur-an states that the Prophet Muhammad was sent to the world as a “mercy to humankind” (21:107). The Qur-an as the holy scripture of Islam is imbued with the spirit of peace, harmony and tolerance. Its culture is not that of war but of understanding, mercy, tolerance, love and compassion (See Maulana Muhammad Ali, Islam: The Religion of Peace. Lahore: Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’at Islam Lahore, 1971; pp. 24-45.).

The word ‘jihad’ is nowhere used in the Qur-an to mean war in the sense of launching an offensive warfare of aggression. It is used rather to mean “struggle”. The action most consistently exhorted in the Qur-an is the exercise of patience (amal-as-sabr). The Prophet Muhammad, in fact did battle only three times in his entire life, and the period of his involvement in these battles did not total more than one and a half days. He fought solely in self-defence, when hemmed-in by aggressors, where he simply had no option (Cf. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, The Prophet of Peace: Teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. Gurgaon: Penguin Books-India, 2014; pp. 26-36.).

Ideological Hatred and the Hijacking of Islam by Violent Religious Extremism

Ideological hatred is a crime against humanity; and any kind of terrorism in the name of ideology, be it religious, racial, political or social, if judged by its result, is a crime against the entire humankind.

It is very hard to obliterate the hatred brought about by an ideology utilizing religion as its basis of legitimation. Ideological hatred generates unnecessary violence and unlimited suffering for both sides. It can murder people without any feelings of remorse at all (Michael Jordan. In the Name of God: Violence and Destruction in the World’s Religions. Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2006; pp. 121-129.). This is why authentic religion must stir away from any acts of terrorism since the avowed message of all religions—universal understanding—is the very opposite of bigotry, and the power of religion if utilized for wrongful purposes can escalate into massive destruction in the same way that positive impact of religion can also produce innumerable good effects in society.

The true goal of any authentic faith-tradition is ultimately based on tolerance, amity and harmony. Authentic religion awakens in its adherents the feelings of well-wishing towards other human beings. Its exponents strive peacefully to pass on the truth that they have discovered for the benefit of their fellow humans. Such religion, far from causing harm to society, becomes a driving force towards ethical and social development of all humanity if utilized for beneficial ends (Cf. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, The Age of Peace. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2015; pp.1-26.).

However, when a particular faith-tradition is hijacked into becoming a violent movement based on pure animosity and hatred, the adherents of this movement would consider those who are not like-minded to be enemies. They have an overpowering desire to exterminate the religious “other”. They hold that the “others” are the obstacles to their avowed goal of global hegemony and seeks to destroy religious “otherness” so that they can put their own belief-system as replacement. As a result of this negative thinking they divide humanity into two camps: one consisting of their enemies, and the other of their friends. The moment they have made this distinction between “us-and-them”, thereafter, they permit their avowed hatred for the “other” to conflagrate into virulent and bloody violence against the religious “other” (See Marc H. Ellis. Unholy Alliance: Religion and Atrocity in our Time. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997; pp. xi-xvii.).

To make matters worse, the hatred felt by religious militancy or violent extremism has become inseparable from its theology and ideology. They hate others who think differently from themselves because they hold them to be ideologically in error and theologically heretical. Experience shows that of all kinds of hatred that is based on an ideology, more particularly those that are based on religious dogmatism or fanaticism are the most destructive—and its target is the total annihilation of enemies.

Not until this end is achieved will it ever die down. This is the reason that ideological hatred takes no time in assuming the shape of violence. When it is found that peaceful means of persuasion are showing no results, arms are then resorted to, so that all enemies may be removed from its path. (Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, What Is Islamic Fundamentalism. Op.cit, pp.19-20.).

In the present time, religious extremism are responsible for actions marked by violence taking place in the name of Islam, thus hijacking the beautiful teachings of Islam into an ideology of hate and violence. They hold that the aim of Islam is to establish an ideal society and an ideal State. But since from their perspective, this task cannot be performed without political strength, armed struggle, and violent militancy, they feel justified in fighting against those in State power. Violent movements with this aim were launched on a large scale during the second half of the twentieth century as reaction to colonization of Muslim lands by Western imperialist powers. The targets of violent actions by Muslim extremists were either the non-Muslim rulers or the secular Muslim rulers. However, despite great losses in terms of life, wealth and resources, these movements failed to produce any beneficial results either to global Islam or to the international community of nations (See Raamish Siddiqui (ed.). The True Face of Islam: Essays of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. Noida: Harper Collins Publishers India, 2015; pp. 207-212.).

While the goal of any authentic religion is based on love and goodwill to humanity; the goal of any group supporting violent extremism is based on hate, enmity, and annihilation of those whom they consider to be enemies. Owing to this life-denying intentionality on the part of violent extremists, all their actions take on the direction of terrorism and carnage. On the other hand, well-known examples of peaceful persuasion and peaceful coexistence can be found in the movements launched by the Sufi saints of Islam across the ages, the target of which was not State confrontation but individual spiritual reformation and social transformation.

The task of these Sufi luminaries and saints in Islam involved the spiritual reformation of people’s hearts and minds, so that they might lead their lives as new, transformed, and exemplary human beings in the midst of the society in which they lived in. Owing to their adherence to this pacifist policy, the Sufi saints of Islam did not need to resort to violence and armed conflict. A fine example in our times is provided by the spiritual reformist Sunni organization Tabligh-i-Jamaat, which has been working peaceably on a large scale in the sphere of individual reform and peaceful societal transformation particularly in India, in South Asia, as well as in Southeast Asia in general (Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. Tabligh Movement. New Delhi: Good Word Books and the Islamic Centre Press, 2003; pp. 45-68.).

Since Islamic fundamentalists target the Islamization of the State rather than the reform of individuals, their only plan of action is to continually launch themselves at war with the rulers who hold sway over the institution of the State. In this way, their movement takes the path of violence from the very beginning of the movement’s founding (See Bernard Lewis, The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror. London: Phoenix Publishing Ltd., 2004; pp. 117-140.).

Then all the other negative things creep-in which are the direct or indirect result of violence: for instance, mutual hatred and disruption of the peace, waste of precious human and economic resources of the country, etc. It would be right and proper to say that Islam is a name for peaceful struggle, while the so-called “Islamic extremism” is the reverse of the avowed goal of the former. Basing on contemporary news reportage, it is quite clear that violence, far from having its origin in the fundamental or essential teachings of Islam, is a direct product of militant extremism by simply name-dropping “Islam” in order for this violent extremists to gain legitimacy among Muslims (Cf. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. Islam and World Peace. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2015; pp. 90-95.).

Violent Religious Extremism Being Supported by Western Colonizers and Neo-colonizers of Muslim Lands

With reference to the Muslims in the contemporary times, the news mostly highlighted in the Western mainstream media relate to violent extremism. Experience has shown that there is nothing more destructive than fanaticism—the driving force of religious violent extremism.

It is indeed very regrettable that Islamic extremism, launched in the name of Islam has been dealing a fatal blow to the genuine image of Islam as a religion of peace, love and mercy. For it is this violent extremism launched by so-called Islamic fundamentalists of the second type that has converted the beautiful image of Islam into an ugly one tarnished by hatred, terrorism, and bloodshed.

According to Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, foremost contemporary Muslim peace-advocate in the Indian Subcontinent, this form of religious extremism utilizing politics as a means to its end can be understood from a historical perspective. At the time of the emergence of modern Western civilization, the greater part of the world was politically dominated by Muslim political powers.

The Ottoman Empire in the West and the Mughal Empire on the East had become symbols of glory for the Muslim Ummah (community). These Muslim empires came into direct conflict with the Western powers and, in the long run, the Muslim empires were vanquished by Western imperialism. This brought to an end the more than 1600 years of global Islamic political hegemony. Thus, Muslims all over the world came to hold that, in the break-up of their empires, the Western powers were the oppressors, while the Muslims were the oppressed. The result of this decline of Islamic world political supremacy was that the entire Muslim world became inimical to Western nations (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, What Is Islamic Fundamentalism?”. New Delhi, India: Good Word Books, 2004; pp.21-ff. See also Bernard Lewis, The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror. Op. cit., pp. 41-54.).

For Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, the main reason for Islamic extremism mutating itself into violent movements has its roots in a certain defeatist mentality which has, unfortunately, been developing among certain sections of Muslim societies since the loss of their empires. A “besieged mentality” inevitably opts for a negative course of action. The possessors of such a mentality consider themselves as the oppressed, and thus they began setting themselves up against their perceived oppressors.

Having this frame of mind, they are willing to engage themselves in any type activity to fight their perceived oppressors, no matter how damaging to the larger humanity or contrary to religion this may be. And as a corollary result of this negative reactionary attitude came the leadership of some Muslim protagonists in the first half of the twentieth century, who utilized Islam from a political and militaristic point of view, according to which Islam was a complete system of State and Muslims had been appointed by God to fulfil the mission of establishing this Islamic State throughout the world (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, The Political Interpretation of Islam. Op.cit.; pp. 65-72.).

This political and radicalized view of Islam, in spite of being a grave misunderstanding of Islam, spread rapidly among Muslims. Given the circumstances of their past history, this political interpretation of Islam was in total consonance with their psychological condition of “besieged mentality” or “fortress outlook”. Thus, due to their negative frame-of-mind, that is neither due to Islamic reasoning nor coming from Islamic teachings, this politicized extremist interpretation soon gained popularity among some sectors within the discontented among Muslims. However, the activities which were an offshoot from this negative psychology, as example, the Taliban mujahidin, ironically, were backed by the military funding from the American government, particularly from the CIA, in a bid to stem the rising tide of the former Soviet Union’s encroachment in North and Central Asia, particularly in Afghanistan (Cf. Michel Chossudovsky. War and Globalization: The Truth Behind September 11. Quezon City: Ibon Books, 2002; pp.18-27, under the heading “Who is Osama bin Laden: Background of the Soviet-Afghan War”. See also Peter Marsden. The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan. London: Zed Books Ltd., 2002; pp. 57-66.).

Before the 1990s, when the former Soviet Union had assumed the position of a hegemonic power in North and Central Asia, and posed a continuing threat to the United States of America, one of the strategies adopted by the United States was to pit the Afghani Muslim fundamentalists (of the second type) called Taliban (Islamic students in a seminary called madrassas) against the Soviet Union, because these fundamentalists were persistently writing and speaking against Communism as being the enemy of Islam.

The United States likewise gave all possible sorts of assistance to the Taliban by establishing more CIA-backed radicalized madrassas throughout Afghanistan and Pakistan. The CIA provided them with weapons to set themselves up against the former Soviet Union and actively assisted the Taliban mujahidin (holy warriors) in the dissemination of their literature proclaiming their fatwa of jihad against Communism all over the world (See Peter Marsden. The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan. Op. cit., pp. 124-152. See also Michel Chossudovsky. America’s War on Terrorism. Montreal: Global Research Publishers, 2005; pp. 17-62.).

However, this “enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend” formula among radicalized violent extremists ultimately proved counterproductive for them, in that it virtually amounted to replacing one enemy with another set of enemy. Those who at a later stage felt the impact of religious extremism took this to be a case of violence against them. So they opted for a policy of an “eye-for-an-eye and a-tooth-for-a-tooth”: for instance, the Taliban mujahidins whom the United States had effectively utilized against the former Soviet Union are now the avowed mortal enemies of the United States’ political and economic interests in Central Asia after the Russians were driven from Afghan lands (See See Peter Marsden. The Taliban: War and Religion in Afghanistan. Op. cit., pp. 153-156. Cf. Michel Chossudovsky. Towards A World War III Scenario: The Dangers of Nuclear War. Quebec: Global Research Publishers, 2012; pp. 35-40.).

However, subsequent events proved this policy to be a total failure, the reason being that the issue was not that of conducting a purely physical struggle, but of exposing and rebutting the fallacies of a flawed ideology: to defeat an ideology, a counter-discourse critiquing another ideology is of great necessity—and not simply countering it with another violent armed response. Nothing can be achieved without this rational ideological discourse and reasoned dialogue that can effectively counter violent extremism with sound logic, rational persuasion and impeccable reasoning (See Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. The Ideology of Peace: Towards a Culture of Peace. New Delhi: Good Word Books, 2004; pp. 7-29.).

Independent News Media and Its Role in Countering Violent Religious Extremism and Islamophobic Portrayal of Islam and Muslims

According to the contemporary renowned Islamic pacifist of India, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, any religious extremism is a threat to peace since due to religious fanaticism; its proponents do not stop short of resorting to destructive activity both to others and to themselves such as suicide attacks and indiscriminate bombings of civilian areas. While it is a fact that in these violent activities only a small group is involved, however this small group has indirect or “quasi-support” of the majority, who remained silent and did not raise any outcry against such inhumanities in the name of Islam. Peace-loving Muslims must therefore disown these violent people who simply utilized and hijacked Islam to further hatred and political-religious extremism. If the majority of peace-loving Muslims will withdraw their indirect support and outrightly condemn Islamic militancy, these fringe groups will lose their mass base of indirect or “quasi-support”. Consequently, this will be the starting point when religious extremists who are directly involved in violent activities will hopefully begin to abandon the path of violence altogether (Cf. Maulana Wahiduddin Khan. Islam and Peace. New Delhi: Good Word Books, pp.164-168.).

It is therefore a very urgent task for the Islamic World and for global Muslims to undertake a proper information campaign as to the real teachings of Islam by making use of the independent media on a full scale in order to make people aware of the fact that this political interpretation of Islam—as capitalized by both violent extremist groups and by Western mainstream media in describing the terroristic activities of so-called Islamic extremists—is absolutely devoid of basis either in the Qur-anor in the examples (As-Sunnah) set by the Prophet Muhammad. As opposed to this misinterpretation, the true values of authentic Islam, based on global peace, universal fraternity, and sincere well-wishing for one-and-all should be presented to the general public by the international independent media, the academe, and international peace advocates.

If this authentic interpretation of Islam can be brought to the attention of general masses through responsible international independent media news outfits in cooperation with peace-loving Muslims and authentic Islamic groups all over the world, then there is great hope that those who have been espousing extremist ideology in the name of Islam will eventually abandon the path of hatred and violence and come back to the genuine Islam—“to the home of peace” (See Qur-an 6:127 and 10:25) as described in the Qur-an and the practice of the Prophet Muhammad.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Prof. Henry Francis B. Espiritu is Associate Professor-VI of Philosophy and Asian Studies at the University of the Philippines (UP), Cebu City. He was Academic Coordinator of the Political Science Program at UP Cebu from 2011-2014. He is presently the Coordinator of Gender and Development (GAD) Office at UP Cebu. His research interests include Islamic Studies particularly Sunni jurisprudence, Islamic feminist discourses, Islam in interfaith dialogue initiatives, Islamic environmentalism, Classical Sunni Islamic pedagogy, the writings of Imam Al-Ghazali on pluralism and tolerance, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Turkish Sufism, Muslim-Christian dialogue, Middle Eastern affairs, Peace Studies and Public Theology. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG)